Polycrates

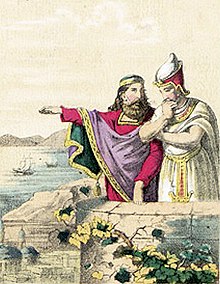

Polycrates with Pharao Amasis II circa 530 BC (19th century illustration).

Polycrates (/pəˈlɪkrəˌtiːz/; Greek: Πολυκράτης, in English usually Polycrates but sometimes Polykrates), son of Aeaces, was the tyrant of Samos from c. 538 BC to 522 BC. He had a reputation as both a fierce warrior and an enlightened tyrant.

Contents

1 Establishment of his power

2 Religious and cultural activities

3 Polycrates' fate

4 Polycrates in later culture

5 See also

6 Notes

7 External links

Establishment of his power

Polycrates took power during a festival of Hera with his brothers Pantagnotus and Syloson, but soon had Pantagnotus killed and exiled Syloson to take full control for himself. He assembled a navy of 100 penteconters, which became the most powerful navy in the Greek world –– Herodotus says that Polycrates was the first Greek ruler to understand the importance of sea power[1] –– and an army of 1,000 archers, and with these forces he implemented a plan to bring all the Greek islands and cities of Ionia under his rule. In pursuit of this goal, he conquered several islands and towns, fought successful actions against Miletus and Lesbos, and formed an alliance with King Amasis of Egypt.[2]

Coinage of Samos at the time of Polycrates. Circa 530-528 BC.

Coinage of Samos at the time of Polycrates. Forepart of winged boar with lion scalp facing in dotted square within incuse square. Circa 526-522 BC.

Under Polycrates the Samians developed an engineering and technological expertise to a level unusual in ancient Greece.[3] They built an aqueduct in the form of a tunnel 1100 yards long which can still be seen and which is known as the Tunnel of Eupalinos. The tunnel was constructed by two teams tunneling from opposite sides of a ridge who met in the middle with an error of only six feet -- a remarkable engineering feat for the time, and one which probably reflects the practical geometry skills which the Samians had learned from the Egyptians. Polycrates also sponsored the construction of a large temple of Hera, the Heraion, to which Amasis dedicated many gifts, and which at 346 feet long was one of the three largest temples in the Greek world at that time, and he upgraded the harbor of his capital city Pythagorion, ordering the construction of a deep-water mole nearly a quarter mile long, which is still used to shelter Greek fishing boats today.[4]

Heraion, Samos

Religious and cultural activities

One use to which Polycrates put his powerful navy was to control the island of Delos, one of the most important religious centers in Greece, control of which would bolster Polycrates' claim to be the leader of the Ionian Greeks.[5][3] In 522 BC Polycrates celebrated an unusual double festival in honour of the god Apollo of Delos and of Delphi; it has been suggested that the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, sometimes attributed to Cynaethus of Chios, was composed for this occasion.[6] Polycrates lived amid great luxury and spectacle[2] and was a patron of the poets Anacreon and Ibycus[7]. The philosopher Pythagoras was also on Samos during his reign but left for Croton about 531 BC, perhaps out of dissatisfaction with his dictatorship.[3] He also attracted to his court, sometimes by offering generous subsidies, an array of prominent craftsmen and professionals from throughout the Greek world, including Eupalinos, the architect of the Tunnel, who was originally from Megara, the famous physician Demodocus of Croton, Rhoikos the architect of the Heraion, and the master metal-worker Theodoros, who had wrought a famous silver bowl which Croesus dedicated at Delphi and which is described by Herodotus, and who also made the ring which was Polycrates' most treasured personal possession. Polycrates established a library on Samos, and showed a sophisticated approach to economic development, importing improved breeds of sheep, goats, and dogs from elsewhere in the Greek world.[4]

Polycrates' fate

The ring of Polycrates is found inside a fish.

Samos, Temple of Hera, Statue of a warrior, 530 BC

Polycrates leaving his daughter to encounter Oroetus.

According to Herodotus, Amasis thought Polycrates was too successful, and advised him to throw away whatever he valued most in order to escape a reversal of fortune. Polycrates followed the advice and threw a jewel-encrusted ring into the sea; however, a few days later, a fisherman caught a large fish that he wished to share with the tyrant. While Polycrates' cooks were preparing the fish for eating, they discovered the ring inside of it. Polycrates told Amasis of his good fortune, and Amasis immediately broke off their alliance, believing that such a lucky man would eventually come to a disastrous end.[8]

It is more likely that the alliance was ended because Polycrates allied with the Persian king Cambyses II against Egypt. By this time, Polycrates had created a navy of 40 triremes, probably becoming the first Greek state with a fleet of such ships. He manned these triremes with men he considered to be politically dangerous, and instructed Cambyses to execute them; the exiles suspected Polycrates' plan, however, and turned back from Egypt to attack the tyrant. They defeated Polycrates at sea but could not take the island.

- Spartan attack

The rebels then sailed to mainland Greece and allied with Sparta and Corinth. Sparta then attempted to invade the island of Samos circa 520. After 40 days they withdrew their unsuccessful siege.[9]

Herodotus also tells the story of Polycrates' death[10]. Near the end of the reign of Cambyses, the governor of Sardis, Oroetus, planned to kill Polycrates, either because he had been unable to add Samos to Persia's territory, or because Polycrates had supposedly snubbed a Persian ambassador. In any case, Polycrates was invited to Magnesia, where Oroetus lived, and despite the prophetic warnings of his daughter, who had apparently dreamt of him hanging in the air, being washed by Zeus and anointed by the Sun God Helios, he went and was assassinated. The manner is not recorded by Herodotus, as it was apparently an undignified end for a glorious tyrant, but he may have been impaled[11] and his dead body was crucified. The prophecy was fulfilled as when it rained he was 'washed by Zeus' and when the sun shone he was 'anointed by Helios', as the moisture was sweated from him.

After the murder of Polycrates by Oroetes, Samos was ruled by Maiandrios.[12] After some time, Syloson, the brother of Polycrates, was installed as governor of Samos by Achaemenid ruler Darius I, receiving the help of general Otanes to expell the imposter who had taken control after Oroetes.[13]

The crucifixion of Polycrates by Oroetes.

The crucifixion of Polycrates the tyrant after his capture by the Persians.

The crucifixion of Polycrates by Achaemenid Satrap Oroetes. Polykrates by M.Kozlovsky (1790, Russian museum).

Polycrates in later culture

Polycrates is mentioned in Byron's famous stanzas "The Isles of Greece:"

- Fill high the bowl with Samian wine!

- We will not think of themes like these!

- It made Anacreon's song divine:

- He served—but served Polycrates—

- A tyrant; but our masters then

- Were still, at least, our countrymen.

Polycrates' Ring (German: Der Ring des Polykrates) is a lyrical ballad written in June 1797 by Friedrich Schiller and first published in his 1798 Musen-Almanach annual. It is about how the greatest success gives reason to fear disaster. Schiller relied on the accounts of the fate of Polycrates, tyrant of Samos, in Herodotus' Histories, Book III.

The early 20th century opera Der Ring des Polykrates by Erich Wolfgang Korngol retells the story of Polycrates as a modern fable.

See also

- Polycrates complex

- Mētiokhos kai Parthenopē

Notes

^ Herodotus 3.122

^ ab Smith, William (1867). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. V. 3. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 459..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abc Grant, Michael. The rise of the Greeks (1st American ed.). New York: Scribners. pp. 153–156.

^ ab Burn, A. R. (1968). The lyric age of Greece. St. Martin's Press: Minerva. pp. 314–318.

^ Bury, J. B.; Mieggs, Russell (1956). A history of Greece to the death of Alexander the Great (3 ed.). London: Macmillan. pp. 232–234.

^ Walter Burkert, 'Kynaithos, Polycrates and the Homeric Hymn to Apollo' in Arktouros: Hellenic studies presented to B. M. W. Knox ed. G. W. Bowersock, W. Burkert, M. C. J. Putnam (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1979), pp. 53–62.

^ See papyrus fragment of a poem by Ibycus that mentions Polycrates at Oxyrhynchus Online: ‘With them you too, Polycrates, shall have immortal fame for beauty as long as my song and fame endure.’

^ Herodotus 3.40-42

^ Hart, John (2014). Herodotus and Greek History (Routledge Revivals). Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 9781317678373.

^ "Herodotus (Polycrates)". global.oup.com. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

^ Herodotus. The Histories (an introduction and notes by John M. Marincola). Penguin Classics, 2003, p. 224.

^ Hart, John (2014). Herodotus and Greek History (Routledge Revivals). Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 9781317678373.

^ Dandamaev, M. A. (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. BRILL. p. 148. ISBN 978-9004091726.The island was plundered and incorporated into the Achaemenid empire. Syloson was appointed as its vassal ruler.

External links

Livius, Polycrates of Samos by Jona Lendering