Alta California

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

| Alta California | |||||

Province in the Viceroyalty of New Spain Territory in independent Mexico | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

Capital | Monterey 36°36′N 121°54′W / 36.600°N 121.900°W / 36.600; -121.900Coordinates: 36°36′N 121°54′W / 36.600°N 121.900°W / 36.600; -121.900 | ||||

Governor (See also complete list) | |||||

| • | 1804–14 | José Joaquín de Arrillaga (first Spanish governor) | |||

| • | 1815–22 | Pablo Vicente de Solá (last Spanish governor) | |||

| • | 1822–25 | Luis Antonio Argüello (first Mexican governor) | |||

| • | 1836 | Nicolás Gutiérrez (last Mexican governor of Alta California) | |||

Historical era | Spanish colonization of the Americas | ||||

| • | Las Californias | 1769 | |||

| • | Las Californias split into Alta and Baja | 1804 | |||

| • | Mexican independence | August 24, 1821 | |||

| • | Centralist Republic of Mexico creates Department of Las Californias | October 23, 1835 | |||

| • | Disestablished | 1836 | |||

Today part of | - - - - - - - - | ||||

Alta California ('Upper California'), known sometimes unofficially as Nueva California ('New California'), California Septentrional ('Northern California'), California del Norte ('North California') or California Superior ('Upper California'),[1] began in 1804 as a province of New Spain. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of Las Californias, but was split off into a separate province in 1804. Following the Mexican War of Independence, it became a territory of Mexico in April 1822[2] and was renamed "Alta California" in 1824. The claimed territory included all of the modern US states of California, Nevada and Utah, and parts of Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico.

Neither Spain nor Mexico ever colonized the area beyond the southern and central coastal areas of present-day California, and small areas of present-day Arizona, so they exerted no effective control in modern-day California north of the Sonoma area, or east of the California Coast Ranges. Most interior areas such as the Central Valley and the deserts of California remained in de facto possession of indigenous peoples until later in the Mexican era when more inland land grants were made, and especially after 1841 when overland immigrants from the United States began to settle inland areas.

Large areas east of the Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges were claimed to be part of Alta California, but were never colonized. To the southeast, beyond the deserts and the Colorado River, lay the Spanish settlements in Arizona.[a][b]

Alta California ceased to exist as an administrative division separate from Baja California in 1836, when the Siete Leyes constitutional reforms in Mexico re-established Las Californias as a unified department, granting it more autonomy.[5][6][7] Most of the areas formerly comprising Alta California were ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican–American War in 1848. Two years later, California joined the union as the 31st state. Other parts of Alta California became all or part of the later U.S. states of Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming.

Contents

1 Spanish colonization

2 Spanish rule

3 Ranchos

4 Independent Mexico

5 Mexican–American War

6 Spanish governors

7 Flags that have flown over California

8 In popular culture

9 See also

9.1 Spanish and Mexican control

9.2 Russian colonies

9.3 United States control

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Spanish colonization

The Spanish explored the coastal area of Alta California by sea beginning in the 16th century and prospected the area as a domain of the Spanish monarchy. During the following two centuries there were various plans to settle the area, including Sebastián Vizcaíno's expedition in 1602–03 preparatory to colonization planned for 1606–07, which was canceled in 1608.

Between 1683 and 1834, Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries established a series of religious outposts from today's Baja California and Baja California Sur into present-day California.[5][6] Father Eusebio Kino missionized the Pimería Alta from 1687 until his death in 1711. Plans in 1715 by Juan Manuel de Oliván Rebolledo resulted in a 1716 decree for extension of the conquest (of Baja California) which came to nothing. Juan Bautista de Anssa proposed an expedition from Sonora in 1737 and the Council of the Indies planned settlements in 1744. Don Fernando Sánchez Salvador researched the earlier proposals and suggested the area of the Gila and Colorado Rivers as the locale for forts or presidios preventing the French or the English from "occupying Monterey and invading the neighboring coasts of California which are at the mouth of the Carmel River."[8][9] Alta California was not easily accessible from New Spain: land routes were cut off by deserts and often hostile Native populations and sea routes ran counter to the southerly currents of the distant northeastern Pacific. Ultimately, New Spain did not have the economic resources nor population to settle such a far northern outpost.[10]

Spanish interest in colonizing Alta California was revived under the visita of José de Gálvez as part of his plans to completely reorganize the governance of the Interior Provinces and push Spanish settlement further north.[11] In subsequent decades, news of Russian colonization and maritime fur trading in Alaska, and the 1768 naval expedition of Pyotr Krenitsyn and Mikhail Levashev, in particular, alarmed the Spanish government and served to justify Gálvez's vision.[12] To ascertain the Russian threat, a number of Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest were launched. In preparation for settlement of Alta California, the northern, mainland region of Las Californias was granted to Franciscan missionaries to convert the Native population to Catholicism, following a model that had been used for over a century in Baja California. The Spanish Crown funded the construction and subsidized the operation of the missions, with the goal that the relocation, conversion and enforced labor of Native people would bolster Spanish rule.

The first Alta California mission and presidio were established by the Franciscan friar Junípero Serra and Gaspar de Portolá in San Diego in 1769. The following year, 1770, the second mission and presidio were founded in Monterey.[13] In 1773 a boundary between the Baja California missions (whose control had been passed to the Dominicans) and the Franciscan missions of Alta California was set by Francisco Palóu. The missionary effort coincided with the construction of presidios and pueblos, which were to be manned and populated by Hispanic people. The first pueblo founded was San José in 1777, followed by Los Ángeles in 1781. (Branciforte, founded in 1797, failed to maintain enough settlers to be granted pueblo status.)

Spanish rule

By law, mission land and property were to pass to the indigenous population after a period of about ten years, when the natives would become Spanish subjects. In the interim period, the Franciscans were to act as mission administrators who held the land in trust for the Native residents. The Franciscans, however, prolonged their control over the missions even after control of Alta California passed from Spain to independent Mexico, and continued to run the missions until they were secularized, beginning in 1833. The transfer of property never occurred under the Franciscans.[14][15]

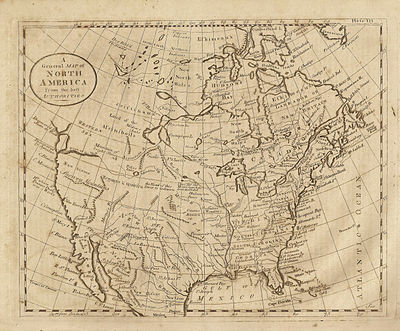

Map of N. America showing California when it was part of New Spain. Map dated 1789 from Dobson's Encyclopedia.

As the number of Spanish settlers grew in Alta California, the boundaries and natural resources of the mission properties became disputed. Conflicts between the Crown and the Church and between Natives and settlers arose. State and ecclesiastical bureaucrats debated over authority of the missions.[16] The Franciscan priests of Mission Santa Clara de Asís sent a petition to the governor in 1782 which stated that the Mission Indians owned both the land and cattle and represented the Ohlone against the Spanish settlers in nearby San José.[17] The priests reported that Indians' crops were being damaged by the pueblo settlers' livestock and that the settlers' livestock was also "getting mixed up with the livestock belonging to the Indians from the mission" causing losses. They advocated that the Natives owned property and had the right to defend it.[18]

In 1804, due to the growth of the Spanish population in new northern settlements, the province of Las Californias was divided just south of San Diego, following mission president Francisco Palóu's division between the Dominican and Franciscan jurisdictions. Governor Diego de Borica is credited with defining Alta (upper) and Baja (lower) California's official borders.[19]

The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, between the United States and Spain, established the northern limit of Alta California at latitude 42°N, which remains the boundary between the states of California, Nevada and Utah (to the south) and Oregon and Idaho (to the north) to this day. Mexico won independence in 1821, and Alta California became a territory of Mexico the next year.

Ranchos

The Spanish and later Mexican governments rewarded retired soldados de cuera with large land grants, known as ranchos, for the raising of cattle and sheep. Hides and tallow from the livestock were the primary exports of California until the mid-19th century. The construction, ranching and domestic work on these vast estates was primarily done by Native Americans, who had learned to speak Spanish and ride horses. Unfortunately, a large percentage of the population of Native Californians died from European diseases. Under Spanish and Mexican rule the ranchos prospered and grew. Rancheros (cattle ranchers) and pobladores (townspeople) evolved into the unique Californio culture.

Independent Mexico

Mexico in 1838. From Britannica 7th edition

Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821 upon conclusion of the decade-long Mexican War of Independence (not acknowledged by Spain until 1836).[citation needed] As the successor state to the Viceroyalty of New Spain, Mexico automatically included the provinces of Alta California and Baja California as territories. Alta California declared allegiance to the new Mexican nation and elected a representative to be sent to Mexico. On November 9, 1822, the first legislature of California was created.[2] With the establishment of a republican government in 1824, Alta California, like many northern territories, was not recognized as one of the constituent States of Mexico because of its small population. The 1824 Constitution of Mexico refers to Alta California as a "territory".

Resentment was increasing toward appointed governors sent from Mexico City, who came with little knowledge of local conditions and concerns.[citation needed] Laws were imposed by the central government without much consideration of local conditions, such as the Mexican secularization act of 1833,[5] causing friction between governors and the people.

Mexican departments created in 1836 (shown after 1845 Texas independence), Las Californias at far left in gray.

In 1836, Mexico repealed the 1824 federalist constitution and adopted a more centralist political organization (under the "Seven Laws") that reunited Alta and Baja California in a single California Department (Departamento de las Californias).[20] The change, however, had little practical effect in far-off Alta California. The capital of Alta California remained Monterey, as it had been since the 1769 Portola expedition first established an Alta California government, and the local political structures were unchanged.

The friction came to a head in 1836, when Monterey-born Juan Bautista Alvarado led a revolt and seized the governorship from Nicolás Gutiérrez. Alvarado's actions began a period of de facto home rule, in which the weak and fractious central government was forced to allow more autonomy in its most distant department. Other Californio governors followed, including Carlos Antonio Carrillo, Alvarado himself for a second time, and Pío Pico. The last non-Californian governor, Manuel Micheltorena, was driven out after another rebellion in 1845. Micheltorena was replaced by Pío Pico, last Mexican governor of California, who served until 1846, when the 1824 constitution was restored.

Mexican–American War

In the final decades of Mexican rule, American and European immigrants arrived and settled in Alta California. Those in Southern California mainly settled in and around the established coastal settlements and tended to intermarry with the Californios. In Northern California, they mainly formed new settlements further inland, especially in the Sacramento Valley, and these immigrants focused on fur-trapping and farming and kept apart from the Californios.

Map of Mexico. S. Augustus Mitchell, Philadelphia, 1847. New California is depicted with a north-eastern border at the meridian leading north of the Rio Grande headwaters.

In 1846, following reports of the annexation of Texas to the United States, American settlers in inland Northern California formed an army, captured the Mexican garrison town of Sonoma, and declared independence there as the California Republic. At the same time, the United States and Mexico had gone to war, and forces of the United States Navy entered into Alta California and took possession of the northern port cities of Monterey and San Francisco. The forces of the California Republic, upon encountering the United States Navy and, from them, learning of the state of war between Mexico and the United States, abandoned their independence and proceeded to assist the United States forces in securing the remainder of Alta California. The California Republic was never recognized by any nation, and existed for less than one month, but its flag (the "Bear Flag") survives as the flag of the State of California, partially as a result of the fact that the Republic's army continued to carry it as a battle flag, for lack of any other means of identification, during the remainder of the war.

After the United States Navy's seizure of the cities of southern California, the Californios formed irregular units, which were victorious in the Siege of Los Angeles, and after the arrival of the United States Army, fought in the Battle of San Pasqual and the Battle of Domínguez Rancho. But subsequent encounters, the battles of Río San Gabriel and La Mesa, were indecisive. The southern Californios formally surrendered with the signing of the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13, 1847. After twenty-seven years as part of independent Mexico, California was ceded to the United States in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The United States paid Mexico $15 million for the lands ceded.

Spanish governors

- 1804 – 25 July 1814 José Joaquín de Arrillaga

- 25 July 1814 – 15 August 1815 José Darío Argüello (acting)

- 15 August 1815 – 11 April 1822 Pablo Vicente de Solá

For Mexican governors see List of Governors of California before admission

Flags that have flown over California

| Spanish Empire, may have been flown by the Portuguese explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542, upon entering the bay of San Diego, and by the Portolá expedition that founded the colony of Alta California in 1769. |

St. George Cross of England, June 1579, voyage of the Golden Hind under Captain Francis Drake at Bodega Bay, Tomales Bay, Drakes Bay or Bolinas Bay (exact location disputed).[21][22][23] | |

| October 1775, the Sonora at Bodega Bay, under Lt. Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra until 1821, when New Spain gained independence from the Spanish Empire. |

| Russian-American Company, by Ivan Alexandrovich Kuskov, the founder of Fort Ross and, from 1812 to 1821, its colonial administrator. The Russian-American Company only controlled a small portion of the northern coast of California, while the entire territory was diplomatically recognized as territory of Mexico; this situation was terminated when the Russians sold Fort Ross in 1841 to John Sutter, and subsequently left the area in 1842. |

| on a ship from Argentina, by Hippolyte Bouchard, a French-born pirate who attacked Monterey Bay from November 24 to November 29, 1818, in order to annoy Spain, who ruled Argentina. Bouchard claimed California on behalf of Argentina, but this claim was never recognized, even by the Argentine government. |

First Mexican Empire, August 24, 1821, Mexico under Emperor Agustín de Iturbide (October 1822, probable time new flag raised in California) until 1823. | |

United Mexican States military, 1823, until January 13, 1847, at Los Angeles. | |

| Flag of California, from 1836, when the Diputación, or Legislature, of California declared independence from Mexico (the Declaration of Independence is available on Wikisource). In 1838, Mexico recognized California as a "free and sovereign state," but this was later rescinded and government from Mexico City was re-established prior to 1846. |

| Bear Flag of the California Republic, June 14, 1846, at Sonoma until July 9, 1846. The California Republic was declared by American citizens who had settled inland (in the valley of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers), and it is thought that the inclusion of one star and one stripe was meant to highlight their American origins. The Republic's existence was never officially recognized by any other government. |

United States of America, July 9, 1846; see History of California. |

For even more Californian flags see: Flags over California, A History and Guide (PDF). Sacramento: State of California, Military Department. 2002..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

In popular culture

- In the second half of the 19th century, there was a San Francisco-based newspaper called The Daily Alta California (or The Alta Californian). Mark Twain's first widely successful book, The Innocents Abroad, was an edited collection of letters written for this publication.

- In the 1998 film, The Mask of Zorro, fictional former Governor Don Rafael Montero plans to purchase the area from Mexico to set up an independent republic, roughly corresponding to historical Alta California.

- The Carl Barks comic book Donald Duck in Old California! provided a glimpse into the lives of the Californios.

See also

|

|

References

Footnotes

^ José Bandini, in a note to Governor Echeandía or to his son, Juan Bandini, a member of the Territorial Deputation (legislature), noted that Alta California was bounded "on the east, where the Government has not yet established the [exact] borderline, by either the Colorado River or the great Sierra (Sierra Nevada)."[3]

^ Chapman explains that the term "Arizona" not used in period. Arizona south of the Gila River was referred to as the Pimería Alta. North of the Gila River were the "Moqui", whose territory was considered separate from New Mexico. The term "the Californias," therefore, refers specifically to the Spanish-held coastal region from Baja California to an undefined north.[4]

Citations

^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1884). History of California. p. 68.without any uniformity of usage, the upper country began to be known as California Septentrional, California del Norte, Nueva California, or California Superior. But gradually Alta California became more common than the others, both in private and official communications, though from the date of the separation of the provinces in 1804, Nueva California became the legal name, as did Alta California after 1824.

^ ab Williams, Mary Floyd (July 1922). "Mission, presidio and pueblo: Notes on California local institutions under Spain and Mexico". California Historical Society Quarterly. 1 (1): 23–35. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

^ A Description of California in 1828 by José Bandini (Berkeley, Friends of the Bancroft Library, 1951), 3. Reprinted in Mexican California (New York, Arno Press, 1976).

ISBN 0-405-09538-4

^ Chapman, Charles Edward (1973) [1916]. The Founding of Spanish California: The Northwestward Expansion of New Spain, 1687–1783. New York: Octagon Books. pp. xiii.

^ abc Ryan, Mary Ellen & Breschini, Gary S. (2010). "Secularization and the Ranchos, 1826–1846". Salinas, CA: Monterey County Historical Society. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

^ ab Robinson, William Wilcox (1979). Land in California: The Story of Mission Lands, Ranchos, Squatters, Mining Claims, Railroad Grants, Land Scrip, Homesteads. Chronicles of California, Volume 419: Management of public lands in the United States. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 29. ISBN 0520038754. Retrieved 30 May 2016. The cortes (legislature) of New Spain issued a decree in 1813 for at least partial secularization that affected all missions in America and was to apply to all outposts that had operated for ten years or more; however, the decree was never enforced in California.

^ Yenne, Bill (2004). The Missions of California. San Diego, CA: Thunder Bay Press. pp. 18f. ISBN 1592233198.

^ Plans for the Occupation of Upper California: A New Look at the "Dark Age" from 1602 to 1769, The Journal of San Diego History, San Diego Historical Society Quarterly, Winter 1978, Volume 24, Number 1

^ The elusive West and the contest for empire, 1713–1763, Paul W. Mapp, Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture

^ Starr, Kevin (2005). California: A History. New York: Modern Library. p. 28. ISBN 978-08129-7753-0.

Rawls, James J.; Walton Bean (2008). California: An Interpretive History (9th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-07-353464-0.

^ Starr, California: A History, 31-32. Rawls and Bean, California: An Interpretive History, 33.

^ Haycox, Stephen W. (2002). Alaska: An American Colony. University of Washington Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-295-98249-6.

^ Starr, California: A History, 35-36. Rawls and Bean, California: An Interpretive History, 37-39.

^ Beebe, 2001, page 71

^ Fink, 1972, pages 63–64.

^ Milliken, 1995, page 2 footnote.

^ Milliken, 1995, page 72–73

^ Milliken, 1995, page 73, quoting Murguia and Pena [1782] 1955:400.

^ Field, Maria Antonia (1914). "California under Spanish Rule". Chimes of Mission Bells. San Francisco: Philopolis Press.

^ See "República Centralista (México)" in the Spanish version of Wikipedia

^ "Biographical Notes: Sir Francis Drake" Wandering Lizard. Consulted on 2008-08-07.

^ Sterling, Richard and Tom Downs. San Francisco: City Guide. (Lonely Planet, 2004), 233–234.

ISBN 978-1-74104-154-5

^ Starr, Kevin. California: A History. (New York: Modern Library, 2005), 25.

ISBN 0-679-64240-4

Further reading

Album of Views of the Missions of California, Souvenir Publishing Company, San Francisco, Los Angeles, 1890s.- Beebe, Rose Marie (2001). Lands of Promise and Despair: Chronicles of Early California, 1535–1846. Berkeley: Heyday Books.

ISBN 1-890771-48-1 - Blomquist, L.R., A Regional Study of the Changes in Life and Institutions in the San Luis Obispo District, 1830–1850 (M.A. thesis, History Department, University of California, Berkeley, 1943). Source consulted by Ryan & Breschini (2010).

- Breschini, G.S., T. Haversat, and R.P. Hampson, A Cultural Resources Overview of the Coast and Coast-Valley Study Areas [California] (Coyote Press, Salinas, CA, 1983). Source consulted by Ryan & Breschini (2010).

California Mission Sketches by Henry Miller, 1856 and Finding Aid to the Documents relating to Missions of the Californias : typescript, 1768–1802 at the Bancroft Library- Fink, Augusta (1972). Monterey, The Presence of the Past. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books.

ISBN 978-8770107204

Howser, Huell (December 8, 2000). "Art of the Missions (110)". California Missions. Chapman University Huell Howser Archive.- Milliken, Randall (1995). A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area 1769–1910. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press Publication.

ISBN 0-87919-132-5

The Missions of California, by Eugene Leslie Smyth, Chicago: Alexander Belford & Co., 1899.

External links

- Worldstatesmen.org: Provinces of New Spain

- Alta California grants in UC Library System Calisphere

Mexican Land Grants of Santa Clara County at the University of California, Berkeley, Earth Sciences & Map Library