Red Arrows

| Red Arrows Royal Air Force Aerobatic Team | |

|---|---|

The Red Arrows in August 2011 | |

| Active | 1965 – present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Role | Aerobatic flight display team |

| Size | 9 Pilots 91 Support members |

| Base |

|

| Nickname(s) | The Reds |

| Motto(s) | Éclat (English: Excellence) |

| Colours | Red, white and blue |

| Commanders | |

| Team Leader/Red 1 | Sqn Ldr Martin Pert |

| Officer Commanding | Wg Cdr Andrew Keith |

| Insignia | |

| Red Arrows Squadron Badge |  |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Trainer |

|

The RAF Red Arrows depart the 2014 Royal International Air Tattoo, England, in a colour scheme that commemorates their 50th year.

The Red Arrows, officially known as the Royal Air Force Aerobatic Team, is the aerobatics display team of the Royal Air Force based at RAF Scampton. The team was formed in late 1964 as an all-RAF team, replacing a number of unofficial teams that had been sponsored by RAF commands.

The Red Arrows have a prominent place in British popular culture, with their aerobatic displays a fixture of British summer events.[1] The badge of the Red Arrows shows the aircraft in their trademark diamond nine formation, with the motto Éclat, a French word meaning "brilliance" or "excellence".

Initially, they were equipped with seven Folland Gnat trainers inherited from the RAF Yellowjacks display team. This aircraft was chosen because it was less expensive to operate than front-line fighters. In their first season, they flew at 65 shows across Europe. In 1966, the team was increased to nine members, enabling them to develop their Diamond Nine formation. In late 1979, they switched to the BAE Hawk trainer. The Red Arrows have performed over 4,800 displays in 57 countries worldwide.[2]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Predecessors

1.2 Establishment

1.3 Later years

2 Pilots

3 The 'Blues'

4 Aircraft

5 Displays

5.1 Display charges

5.2 Transits

5.3 Smoke

6 Incidents and accidents

7 Video game

8 References

9 External links

History

Predecessors

The Red Arrows were not the first RAF aerobatics team. An RAF pageant was held at Hendon in 1920 with teams from front-line biplane squadrons.

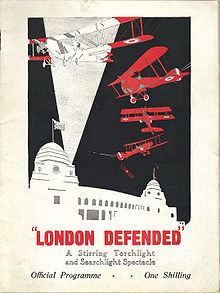

"London Defended" 1925 Official Programme

In 1925, No. 32 Squadron RAF flew an air display six nights a week entitled "London Defended" at the British Empire Exhibition. Similar to the display they had done the previous year, when the aircraft were painted black, it consisted of a night-time air display over the Wembley Exhibition flying RAF Sopwith Snipes which were painted red for the display and fitted with white lights on the wings, tail, and fuselage. The display involved firing blank ammunition into the stadium crowds and dropping pyrotechnics from the aeroplanes to simulate shrapnel from guns on the ground. Explosions on the ground also produced the effect of bombs being dropped into the stadium by the aeroplanes. One of the pilots in the display was Flying Officer C. W. A. Scott, who later became famous for breaking three England Australia solo flight records and winning the MacRobertson Air Race with co-pilot Tom Campbell Black in 1934.[3][4]

In 1938, three Gloster Gladiators flew with their wing tips tied together.[citation needed] Formation aerobatics largely stopped during the Second World War.

In 1947, the first jet team of three de Havilland Vampires came from RAF Odiham Fighter Wing. Various teams flew the Vampire, and in 1950, No. 72 Squadron was flying a team of seven. No. 54 Squadron became the first RAF jet formation team to use smoke trails. Vampires were replaced by Gloster Meteors, No. 66 Squadron developing a formation team of six aircraft.

Hawker Hunter aircraft were first used for aerobatics teams in 1955, when No. 54 Squadron flew a formation of four.

The official RAF team was provided by No. 111 Squadron in 1956, and for the first time, the aircraft had a special colour scheme, which was an all-black finish. After a demonstration in France, they were hailed as "Les Fleches Noires" and from then on known as the Black Arrows. This team became the first team to fly a five-Hunter formation. In 1958, the Black Arrows performed a loop and barrel roll of 22 Hunters, a world record for the greatest number of aircraft looped in formation. The Black Arrows were the premier team until 1961, when the Blue Diamonds (No. 92 Squadron) continued their role, flying 16 blue Hunters.

In 1960, the Tigers (No. 74 Squadron) were re-equipped with the supersonic English Electric Lightning and performed wing-overs and rolls with nine aircraft in tight formation. They sometimes gave co-ordinated displays with the Blue Diamonds.

Yet another aerobatics team was formed in 1960 by No. 56 Squadron, the Firebirds, with nine red and silver Lightnings.

In 1964, the Red Pelicans, flying six BAC Jet Provost T Mk 4s, assumed the role of the RAF's leading display team. In that same year, a team of five yellow Gnat trainers from No 4 Flying Training School displayed at the Farnborough Airshow. This team became known as the Yellowjacks after Flight Lieutenant Lee Jones's call sign, "Yellowjack".

In 1964, all the RAF display teams were amalgamated, as it was feared pilots were spending too much time practising formation aerobatics rather than operational training. The new team name took the word "red" from the fact that the Yellowjacks' planes had been painted red (for safety reasons, as it was a far clearer and more visible colour in the sky) and "arrows" after the Black Arrows; the official version, however, is that the red was a tribute to the Red Pelicans.[5] Another reason for the change to red was that responsibility for the team moved from Fighter Command to the Central Flying School, whose main colour was red.

Establishment

Gnat T.1s on the flightline at RAF Kemble in 1973

The Royal Air Force Aerobatic Team, the formal name of the Red Arrows, began life at RAF Fairford in Gloucestershire, then a satellite of the Central Flying School. The Red Arrows moved to RAF Kemble, now Cotswold Airport, in 1966 after RAF Fairford became the place of choice for BAC to run test flights for Concorde.[citation needed] When RAF Scampton became the CFS headquarters in 1983, the Red Arrows moved there. As an economy measure, Scampton closed in 1995, so the Red Arrows moved just 20 miles to RAF Cranwell; however, as they still used the air space above Scampton, the emergency facilities and runways had to be maintained. Since 21 December 2000, the Red Arrows have been based again at RAF Scampton, near Lincoln.

Hawk T.1s on the flightline at RAF Mildenhall in 1985

The first team, led by Squadron Leader Lee Jones, had seven display pilots and flew the Folland Gnat T1 jet trainer. The first display in the UK was on 6 May 1965, at Little Rissington for a press day. At the subsequent National Air Day display, three days later, at Clermont Ferrand in France, one French journalist described the team as "Les Fleches Rouges", confirming the name "The Red Arrows". By the end of their first season, the Red Arrows had displayed 65 times in Britain, France, Italy, Holland, Germany, and Belgium and were awarded the Britannia Trophy by the Royal Aero Club for their contribution to aviation.

In 1968, the then team leader (Sqn Ldr Ray Hanna) expanded the team from seven to nine jets, as he wanted to expand the team's capabilities and the permutations of formation patterns. During this season, the 'Diamond Nine' pattern was formed and it has remained the team's trademark pattern ever since. Ray Hanna served as Red Leader for three consecutive years until 1968 and was recalled to supersede Squadron Leader Timothy Nelson for the 1969 display season, a record four seasons as Leader, which still stands.[6] For his considerable achievements of airmanship with the team, Ray Hanna was awarded a bar to his existing Air Force Cross.

After displaying 1,292 times in the Folland Gnat, the Red Arrows took delivery of the BAE Hawk in the winter of 1979. Since being introduced into service with the Red Arrows, the Hawk has performed with the Red Arrows in 50 countries.

Later years

Red Arrows perform a manoeuvre called the "Spaghetti Break" over RAF Scampton, September 2015

In July 2004, speculation surfaced in the British media that the Red Arrows would be disbanded, after a defence spending review, due to running costs between £5 million and £6 million.[7] The Arrows were not disbanded and their expense has been justified through their public relations benefit of helping to develop business in the defence industry and promoting recruitment for the RAF. According to the BBC, disbanding the Red Arrows will be highly unlikely, as they are a considerable attraction throughout the world. This was reiterated by Prime Minister David Cameron on 20 February 2013,[8] when he guaranteed the estimated £9m per annum costs while visiting India to discuss a possible sale of Hawk aircraft to be used by India's military aerobatics team, the Surya Kiran.

With the planned closure of RAF Scampton, the future home of the Red Arrows became uncertain. On 20 May 2008, months of speculation were ended when it was revealed that the Ministry of Defence were moving the Red Arrows to nearby RAF Waddington.[9] However, in December 2011, those plans were put under review.[10] The Ministry of Defence confirmed in June 2012 that the Red Arrows would remain at RAF Scampton until at least the end of the decade. Scampton's runway was resurfaced as a result.[11]

In July 2018 the RAF announced that RAF Scampton would close by 2022, and that the Red Arrows would be relocated to another base at some point.[12]

Pilots

Since 1966, the team has had nine display pilots each year, all volunteers. Pilots must have completed one or more operational tours on a fast jet such as the Tornado, Harrier, or Typhoon, have accumulated at least 1,500 flying hours, and have been assessed as above average in their operational role to be eligible. Even then, more than ten pilots apply for each place on the team.[13] Pilots stay with the Red Arrows for a three-year tour of duty. Three pilots are changed every year, such that normally three first-year pilots, three second-year pilots, and three in their final year are on the team. The team leader also spends three years with the team. The 'Boss', as he is known to the rest of the team, is always a pilot who has previously completed a three-year tour with the Red Arrows, often (although not always) including a season as the leader of the Synchro Pair.

During the second half of each display, the Red Arrows split into two sections. Reds 1 to 5 are known as 'Enid' (named after Enid Blyton, author of the Famous Five books) and Reds 6 to 9 are known as 'Gypo' (the nickname of one of the team's pilots back in the 1960s). Enid continue to perform close-formation aerobatics, while Gypo perform more dynamic manoeuvres. Red 6 (Syncro Leader) and Red 7 (Synchro 2) make up the Synchro Pair and they perform a series of opposition passes during this second half. At the end of each season, one of that year's new pilots will be chosen to be Red 7 for the following season, with that year's Red 7 taking over as Red 6.

The pilots line up for an official photo after their display in June 2004

The Reds have no reserve pilots, as spare pilots would not perform often enough to fly to the standard required, nor would they be able to learn the intricacies of each position in the formation. If one of the pilots is not able to fly, the team flies an eight-plane formation. However, if the Team Leader, 'Red 1', is unable to fly, then the team does not display at all. Each pilot always flies the same position in the formation during a season. The pilots spend six months from October to April practising for the display season. Pilots wear green flying suits during training, and are only allowed to wear their red flying suits once they are awarded their Public Display Authority at the end of winter training.[14]

The new pilots joining the team spend their first season flying at the front of the formation near the team leader. As their experience and proficiency improve, they move to positions further back in the formation in their second and third seasons. Pilots who start on the left of the formation stay on that side for the duration of their three-year tour; the pilots on the right side stay on the right. The exception to this are Reds 6 and 7 (the Synchro Pair), who fly in the 'stem' of the formation - the two positions behind the team leader.

During an aerobatics display, Red Arrows pilots experience forces up to five times that of gravity (1 G), and when performing the aerobatic manoeuvre 'Vixen Break', forces up to 7 G can be reached, close to the 8-G structural limit of the aircraft.

As well as the nine pilots, 'Red 10', who is the team supervisor, is a fully qualified Hawk pilot who flies the tenth aircraft when the Red Arrows are away from base. This means the team have a reserve aircraft at the display site. Red 10's duties include co-ordination of all practices and displays and acting as the team's ground safety officer. Red 10 often flies TV cameramen and photographers for air-to-air pictures of the Red Arrows and also provides the commentary for all of the team's displays.[15]

The Red Arrows at the 2018 RIAT, England

On 13 May 2009, it was announced that the Red Arrows would include their first female display pilot. Flt Lt Kirsty Moore (née Stewart) joined for the 2010 season. [16] Flt Lt Moore was not the first female to apply to become a Red Arrow, but was the first to be taken forward to the intense final selection process. She joined the RAF in 1998 and was a qualified flying instructor on the Hawk aircraft at RAF Valley. Prior to joining the team, she flew the Tornado GR4 at RAF Marham.[17]

The 'Blues'

The engineering team that supports the Red Arrows is known as "The Blues" and consists of 85 members drawn from various technical (and support) trades in the RAF.[15] Each season nine members of the Blues are selected to be members of the 'Circus'. The position of "Circus 1" (the engineer who accompanies the "Boss", Red 1) is normally occupied by the Junior Engineering Officer. Similarly, the position of Circus leader (Red 6 or 7) is occupied by a technician of sergeant rank; the other slots being filled by technicians holding corporal or senior aircraftsman/woman (SAC(W)) rank. Each member of the Circus works with the same pilot for the duration of the season and is responsible for servicing their aircraft and preparing their flying kit prior to each display. Circus members fly in the back seats of the jets during transit flights.

Aircraft

A Hawk T1A of the Red Arrows with new 2015 colour scheme

The team use the same two-seat training aircraft used for advanced pilot training, at first the Folland Gnat which was replaced in 1979 by the BAE Hawk T1.[18] The Hawks are modified with an uprated engine and a modification to enable smoke to be generated; diesel is mixed with a coloured dye and ejected into the jet exhaust to produce either red, white or blue smoke.[18]

Displays

The Red Arrows in formation with two Supermarine Spitfires at RIAT 2005

The first display by the Red Arrows was at RAF Little Rissington on 6 May 1965. The display was to introduce the Royal Air Force Aerobatic Team to the media. However, the first public display was on 9 May 1965 in France, at the French National Air Day in Clermont-Ferrand. The first public display in the UK was on 15 May 1965 at the Biggin Hill International Air Fair. The first display with nine aircraft was on 8 July 1966 at RAF Little Rissington.

The first display in Germany was at RAF Laarbruch on 6 August 1965. The Red Arrows performed in Germany a further 170 times before formation aerobatics were banned in Germany following the Ramstein airshow disaster in 1988.

During displays, the aircraft do not fly directly over the crowd apart from entering the display area by flying over the crowd from behind; any manoeuvres in front of and parallel to the audience can be as low as 300 feet (91 m), the 'synchro pair' can go as low as 100-foot (30 m) straight and level, or 150-foot (46 m) when in inverted flight. To carry out a full looping display the cloud base must be above 4,500 feet (1,400 m) to avoid the team entering the cloud while looping. If the cloud base is less than 4,500-foot (1,400 m) but more than 2,500-foot (760 m) the Team will perform the Rolling Display, substituting wing-overs and rolls for the loops. If the cloud base is less than 2,500-foot (760 m) the Team will fly the Flat Display, which consists of a series of fly-pasts and steep turns.

The Red Arrows in Apollo formation, 2010

The greatest number of displays flown in any year was in 1995, when the Red Arrows performed 136 times. The smallest number of displays in one year was in 1975, after the 1973 oil crisis limited their appearances. At a charity auction in 2008, a British woman paid £1.5 million to fly with them.[19]

By the end of the 2009 season, the Red Arrows had performed a total of 4,269 displays in 53 countries.[20] The 4,000th display was at RAF Leuchars during the Battle of Britain Airshow in September 2006.[21]

Following the accidents during the 2011 season, the Red Arrows retained Red 8 and moved the original Red 10 to the Red 5 position to enable them to continue displaying with nine aircraft. In March 2012, the MOD announced that the Red Arrows would fly aerobatic displays with seven aircraft during the 2012 display season as Flt Lt Kirsty Stewart had moved into a ground-based role with the team. It is believed this was due to the emotional stress she had been suffering over the loss of her two Red Arrows colleagues the previous year. As a consequence of this, Red 8 also dropped out of the display team to enable an odd number of aircraft to perform and thus maintain formation symmetry. However, the team carried out official flypasts with nine aircraft by utilising Red 8 as well as ex-Red Arrow display pilot and current Red 10 Mike Ling. The Red Arrows returned to a full aerobatic formation of nine aircraft in 2013.[22]

The Red Arrows with their 50th anniversary tail markings visible at the Eastbourne Airshow 2014

In 2014, The Red Arrows celebrated 50 years of Aerobatic history as a display team returning to RAF Fairford for the Royal International Air Tattoo. For the entirety of the 2014 display season, the aircraft carried special 50th Anniversary markings on their tails instead of just the red, white and blue stripes.

After the 2016 display season, the Red Arrows embarked on an Asia-Pacific and Middle East Tour. They performed flypasts or displays in Karachi in Pakistan; Hindon and Hyderabad in India; Dhaka in Bangladesh; Singapore; Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia; Danang in Vietnam; Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Zhuhai in China; Muscat in Oman; Manama in Bahrain; Abu Dhabi and Kuwait.[23] The programme was the first time the team had displayed in China, and the first time a British military aircraft had deployed to Vietnam.

The summer 2019 display season is expected to take the team on a tour of North America, to be known as Western Hawk 19. After performing at the Royal International Air Tattoo (RIAT), the team will depart across the Atlantic at the end of July. As well as performing at US and Canadian air shows, they are expected to promote the UK through school visits and meetings with business leaders.[24]

Display charges

In 1977, a charge of £200 was introduced by the MOD for a Red Arrows display. By 2000, the charge had risen to £2,000 (including VAT and insurance). In 2011 the team manager quoted the charge as £9,000.[25]

Transits

On a transit flight (getting to or from a display location) the team may fly at the relatively low altitude of 1,000 feet (300 m). This avoids the complication of moving though the cloud base in formation, and also avoids much controlled air space. Jets are more efficient at higher altitude, so longer flights are made at 35,000 to 42,000 feet (11,000 to 13,000 m). On transit flights, the formation can include spare planes. Sometimes a C-130 Hercules accompanies them, carrying spare parts. They often provide flypasts and brief displays to smaller events if they are already passing over or it is a small detour.

Red Arrows with red and blue smoke, in April 2016 at Tanagra Air Base in Greece

As the fuel capacity of the Hawk sets a limit to nonstop flight distance, and the Hawk is incapable of air-to-air refuelling, very long flights between display sites may need landings on the way to refuel. For example, a flight from RAF Scampton to Quebec for an international air display team competition had to be done in seven hops: RAF Scampton, RAF Kinloss (Scotland), Keflavík (Iceland), Kangerlussuaq (west Greenland), Narsarsuaq (south tip of Greenland), Goose Bay (Newfoundland), Bagotville, Quebec.

For the same reason, Red Arrows displays in New Zealand are unlikely because there is no land near enough for a Hawk to land and refuel to reach New Zealand on the most fuel that it can carry.

Smoke

The smoke trails left by the team are made by releasing diesel into the exhaust; this vaporizes in the hot exhaust flow, then re-condenses into very fine droplets that give the appearance of a white smoke trail. Dyes can be added to produce the red and blue colour. The diesel is stored in the pod on the underside of the plane; it houses three tanks: one 50-imperial-gallon (230 L) tank of pure diesel and two 10-imperial-gallon (45 L) tanks of blue and red dyed diesel. The smoke system uses 10-imperial-gallon (45 L) per minute; therefore each plane can trail smoke for a total of seven minutes: – five minutes of white smoke, a minute of blue and a minute of red.

Incidents and accidents

- 26 March 1969 (1969-03-26): A Gnat hit trees while joining formation during a practice at RAF Kemble. Flt Lt Jerry Bowler (no ejection) was killed.[26]

- 16 December 1969 (1969-12-16): Two Gnats crashed, one at Kemble and the other in a field near Chelworth. The pilots both ejected safely although a fire warning from air traffic was intended for only one of the aircraft.[27]

- 20 January 1971 (1971-01-20): Two Gnats collided during the cross-over manoeuvre, over the runway at Kemble with four fatalities.[28]

- 17 May 1980 (1980-05-17): A Hawk hit a yacht mast at an air show in Brighton, Sussex. The pilot, Sqn Ldr Steve Johnson, ejected safely.[28]

- 21 March 1984 (1984-03-21): A Hawk hit the ground at RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus, while practising a loop. The pilot, Flt Lt Chris Hurst, suffered serious injuries when the impact with the ground forced the ejection seat through the canopy and deployed the chute, dragging him out.[29]

- 1986 (1986): A Hawk rammed into the back of another on a runway.

- 16 November 1987 (1987-11-16): Two Hawks collided during a winter training practice with one aircraft crashing into a house in the village of Welton, Lincolnshire. The aircraft of Flt Lt Spike Newbery struck the aircraft of new Team Leader Sqn Ldr Tim Miller from behind, knocking off the tail. Both pilots ejected successfully. Flt Lt Newbery suffered a broken leg and had to leave the team.[30]

- 24 June 1988 (1988-06-24): A Hawk crashed whilst attempting to take off, and the fuel tanks exploded. The pilot ejected safely.[31]

- 1988 (1988): Flt Lt Neil MacLachlan died practising a "roll back" at RAF Scampton.[32]

- 17 October 1998 (1998-10-17): Flt Lt R. Edwards landed short of the runway after a practice run at the Red Arrows then home base, RAF Cranwell, and ejected safely at low altitude.[33]

- 9 September 2003 (2003-09-09): A Hawk overshot the runway while landing at Jersey Airport in advance of an air display. The pilot ran the jet into a gravel pile and little damage was sustained.[34]

- 2007 (2007): The wingtip of a Hawk hit the tail of another during a practice flight near RAF Scampton.[35]

- 23 March 2010 (2010-03-23): Two Hawks were involved in a mid-air collision. The synchro pair were practising one of their manoeuvres when the two aircraft collided. Red 7 (Flt Lt David Montenegro) landed his plane safely, but Red 6 (Flt Lt Mike Ling) ejected and suffered a dislocated shoulder. The incident took place during pre-season training in Crete. Due to his injuries, Flt Lt Ling was unable to participate in the forthcoming display season and was replaced by 2008's Red 6, Flt Lt Paul O'Grady.[36]

- 20 August 2011 (2011-08-20): A Hawk aircraft crashed into a field near Throop Mill, one mile from Bournemouth Airport following a display at the Bournemouth Air Festival. Flt Lt Jon Egging, pilot of Red 4 (XX179), died in the accident.[37] The investigation into the incident determined that Flt Lt Egging was incapacitated due to the effects of g-LOC until very shortly before impact.[citation needed]

- 8 November 2011 (2011-11-08): Pilot Flt Lt Sean Cunningham was ejected from his aircraft while it was on the ground at RAF Scampton and subsequently died from his injuries. He was shot 220 feet (67 m) into the air and received fatal injuries when his parachute failed to open. The UK Health and Safety Executive announced in 2016 that it would be prosecuting the ejection seat manufacturer Martin-Baker for breach of Health and Safety law.[38][39][40] The company has since pleaded guilty to breaching Section 3(1) of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974.[41]

- 20 March 2018: A Hawk crashed at RAF Valley. Two people, the pilot and an engineer, were on board at the time. The pilot of Red 3, Flt Lt David Stark, was hospitalised with non-life-threatening injuries whilst the engineer, Cpl Jonathan Bayliss, was killed.[42][43] Flt Lt Stark was unable to resume his place in the 2018 display team and was replaced by Sqn Ldr Mike Ling, outgoing Red 10.

| Wikinews has related news: Red Arrows pilot killed at 2011 Bournemouth air display |

Video game

In 1985, Database Software released a flight simulator called Red Arrows, made in cooperation with the flight team. In the simulator, stunts have to be performed while flying in formation. It was available for the ZX Spectrum, Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC, Acorn Electron, BBC Micro and Atari.[44]

References

^ "Why everyone loves the Red Arrows". BBC. 10 April 2017. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "Red Arrows - Royal Air Force". www.raf.mod.uk. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

^ Scott, C.W.A. Scott's Book, the life and Mildenhall-Melbourne flight of C. W. A. Scott, London : Hodder & Stoughton, 1934., Bib ID 2361252 Chapter 3, Aerobatics

^ London Defended Torchlight and Searchlight spectacle, The Stadium Wembley May 9 to June 1, 1925 official programme. London: Fleetway Press

^ "Team History". Royal Air Force Arrows. 2012. Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

^ "Ray Hanna Recalled to Red Arrows". Flight International. 26 June 1969. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

^ Duffy, Jonathan (20 July 2004). "Why everyone loves the Red Arrows". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

^ "Red Arrows 'future safe under David Cameron'". BBC News. 20 February 2013. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

^ "Red Arrows moving to new RAF base". BBC News. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

^ "Red Arrows RAF Scampton move plan to be reviewed". BBC News. 16 December 2011. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

^ "RAF units to remain at Scampton". Estate and Environment. Ministry of Defence. 18 June 2012. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

^ "Red Arrows air base to be sold off". 24 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

^ "The Red Arrows" Archived 26 September 2004 at the Wayback Machine from BBC Jersey, 9 September 2004. Retrieved 18 April 2005.

^ "The Reds' Year". Royal Air Force. 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

^ ab "The Support Team". Royal Air Force. 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

^ "2010 Team Announced". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

^ "First female pilot for Red Arrows". BBC News. 12 May 2009. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

^ ab "Red Arrows - Royal Air Force". www.raf.mod.uk. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

^ "Planespotter pays $3.2m for Red Arrows ride". www.meeja.com.au. 3 September 2008. Archived from the original on 22 March 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

^ "Best of British". Royal Air Force. 2009. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

^ "Team History". Royal Air Force. 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

^ https://www.google.com/hostednews/ukpress/article/ALeqM5j5lURBGbDPtBGuU8Ty_BTYv9zHKA?docId=N0892591330839602757A

^ "Asia-Pacific & Middle East Tour 2016". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

^ Lancaster, Mark (23 January 2019). "Royal Air Force Aerobatic Team - North American Tour 2019 :Written statement - HCWS1264". UK Parliament. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

^ "Red Arrow Rookies" documentary broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 19 January 2011.

^ Halley 2001, p. 77

^ "Red Arrow pilot ejects in error". News. The Times (57745). London. 17 December 1969. col F, p. 3.

^ ab "Red Arrows Losses and Ejections". Ejection History. 25 April 2007. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

^ "Red Arrows Losses & Ejections". Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

^ "Welton Village News". Old Welton Village. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

^ "Pilot Ejects Safely From Burning Jet". St. Louis Post Dispatch. 26 June 1988. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

^ "A brief history of the Red Arrows". The Telegraph. 20 August 2011. Archived from the original on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

^ "Red Arrows Losses and Ejections". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

^ "Red Arrows jet in runway drama". BBC News. 9 September 2003. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

^ "Red Arrows in mid-air collision". BBC News. 12 January 2007. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

^ "Red Arrows Collide During Greek Training". Sky News. 23 March 2010. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

^ "Red Arrows pilot dies in Bournemouth Air Festival crash". BBC News Online. BBC. 20 August 2011. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

^ "Red Arrows pilot dies after incident at RAF Scampton". BBC. 8 November 2011. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

^ "Daredevil Red Arrows pilot dies after 'ejector crash'". news.com.au. 8 November 2011. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

^ "Red Arrows pilot death: Ejector seat firm to be prosecuted". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

^ "Red Arrows ejector seat firm guilty over RAF Scampton death". Retrieved 22 January 2018.

^ "Red Arrow aircraft crashes at RAF Valley". BBC News. 20 March 2018. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

^ "Red Arrows crash: Cpl Jonathan Bayliss named as victim". BBC News. 21 March 2018. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

^ "Red Arrows". SpectrumComputing. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

Halley, James (2001). Royal Air Force Aircraft XA100 to XZ999. Air-Britain. ISBN 0-85130-311-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Red Arrows. |

- Official website

BBC Archive video from Go With Noakes in 1976 at RAF Kemble