Illegal immigration to the United States

[dummy-text]

Illegal immigration to the United States

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Illegal immigration or undocumented immigration to the United States includes both unlawful entry of foreign nationals into the United States and remaining in the country after the expiration of their entry visa or parole documents.[1] Illegal immigration has been a matter of strong debate in the United States since the 1980s, and has been a major focus of President Donald Trump, as illustrated by his campaign to build a wall along the Mexico border.

Research shows that illegal immigrants increase the size of the U.S. economy/contribute to economic growth, enhance the welfare of natives, contribute more in tax revenue than they collect, reduce American firms' incentives to offshore jobs and import foreign-produced goods, and benefit consumers by reducing the prices of goods and services.[2][3][4][5] Economists estimate that legalization of the illegal immigrant population would increase the immigrants' earnings and consumption considerably, and increase U.S. gross domestic product.[6][7][8][9] There is scholarly consensus that illegal immigrants commit less crime than natives.[10][11]Sanctuary cities—which adopt policies designed to avoid prosecuting people solely for being in the country illegally—have no statistically meaningful impact on crime, and may reduce the crime rate.[12][13] Research suggests that immigration enforcement has no impact on crime rates.[14][15][12]

The illegal immigrant population of the United States peaked by 2007, when it was at 12.2 million and 4% of the total U.S. population.[16][17] Estimates in 2016 put the number of unauthorized immigrants at 10.7 million, representing 3.3% of the total U.S. population.[16] Since the Great Recession, more undocumented immigrants have left the United States than entered it, and illegal border crossings are at the lowest in decades.[18][19][20][21] Since 2007, visa overstays have accounted for a larger share of the growth in the undocumented immigrant population than illegal border crossings,[22] which have declined considerably from 2000 to 2018.[23] In 2012, 52% of unauthorized immigrants were from Mexico, 15% from Central America, 12% from Asia, 6% from South America, 5% from the Caribbean, and another 5% from Europe and Canada.[24] As of 2016, approximately two-thirds of unauthorized adult immigrants had lived in the U.S. for at least a decade.[16]

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 uldisplay:none

Contents

1 Definitions

2 History

3 Profile and demographics

3.1 Breakdown by state

3.2 Population

3.3 Children

3.4 2011–2016 surge in unaccompanied minors from Central America

3.5 2018 zero tolerance policy

3.6 Countries of origin

3.7 Trends

3.8 Illegal entry

3.9 Visa overstay

3.10 Border Crossing Card violation

3.11 In the workforce

3.12 Organized migrant caravans

4 Causes

4.1 Causes by region

4.2 Economic incentives

4.3 Channels for legal immigration

4.4 Family reunification

4.5 Further incentives

5 International controversies

5.1 Mexican federal and state government assistance

6 Legal issues

6.1 Improper entry

6.2 Visa overstay

6.3 Unlawful residence

6.4 Employment

6.5 Apprehension

6.5.1 At workplace

6.6 Detention

6.7 Deportation

6.7.1 The AEDPA and IIRIRA Acts of 1996

6.7.2 The USA Patriot Act

6.7.3 Complications of birthright citizen children and illegal immigrant parents

6.8 DREAM Act

6.9 Deportation trends

6.10 Military involvement

6.11 Sanctuary cities

6.12 Attacks on immigrants

6.13 Community-based involvement

7 Economic impact

7.1 Native welfare

7.2 Fiscal effects

7.3 Mortgages

8 Crime and law enforcement

8.1 Relationship between illegal immigration and crime

8.2 Impact of immigration enforcement

8.3 Gang activity

8.4 Identity theft

9 Education

10 Harm to illegal immigrants

10.1 Health

10.2 Exploitation by employers

10.3 Prostitution

10.4 Death

10.5 Workplace injury

11 Public opinion and controversy

11.1 United States economy

11.2 Opinions from influential groups in society

11.2.1 Investors

11.3 Response of government

11.3.1 Federal response

11.3.2 State and local response

11.3.2.1 Sanctuary cities

11.3.3 Enforcement

11.4 Culture

12 Cultural references

12.1 Commercial films

12.2 Documentary films

13 See also

14 References

15 Further reading

16 External links

Definitions[edit]

The categories of foreign-born people in the United States are:

- US citizens born as citizens outside the United States

- US citizens born outside the United States (naturalized and citizens by adoption)[25]

- Foreign-born non-citizens with current status to reside and/or work in the US (documented)[26]

- Foreign-born non-citizens without current status to reside and/or work in the US

- Foreign-born non-citizens who are prohibited from entry (illegal and also inadmissible)[27]

The latter two constitute illegal or undocumented immigrants.

Non-citizen residence can be or become illegal in one of four ways: by unauthorized entry, by failure of the employer to pay worker documentation fees, by staying beyond the expiration date of a visa or other authorization, or by violating the terms of legal entry.[28][not in citation given][29][not in citation given]

History[edit]

Fewer than seven years after ex-slaves had been granted citizenship in the Fourteenth Amendment, immigration controls were enacted with the Page Act of 1875, banning Chinese women, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, expanded to all Chinese immigrants.[30] A 1904 court decision defined illegal aliens as lacking constitutional rights.[a]Theodore Roosevelt signed the Naturalization Act of 1906, requiring immigrants to learn English in order to become citizens. In the third year of World War I, the Immigration Act of 1917 defined aliens with a long list of undesirables, including most Asians.[31] The U.S. had otherwise nearly open borders until the early 20th century,[32][33][34] with only 1% rejected from 1890–1924, usually because they failed the mental or health exam.[35][36]

The Immigration Act of 1924, signed just a week before Native Americans were granted citizenship, established visa requirements and enacted quotas for immigrants from specific countries, especially targeting Southern and Eastern Europeans,[35] particularly Italians and Jews,[37][38] and effectively prohibited virtually all Asians from immigrating to America.[39] The quotas were eased in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, and a year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on national origin,[37]an immigration and nationality act abolished the quota system while establishing other limits. A 1990 act increased the annual immigrant limit to 675,000 per year.

The debate over illegal immigration has continued amongst the fear of potential terrorist attacks in the wake of the September 11 attacks in 2001 and the lack of an effective Mexico–United States barrier. President Donald Trump enacted a travel ban from seven Muslim-majority countries which had been identified by Obama as countries of concern, which was struck down as unconstitutional and replaced by a "watered down, politically correct version".[40] During his successful election campaign, Trump promised to make Mexico pay for a new border wall. The federal government entered a partial shutdown from December 22, 2018 to January 25, 2019 in a standoff over Trump's demand for $5.7 billion in funding for the wall.

Profile and demographics[edit]

This section needs to be updated. (August 2017) |

In 2012, an estimated 14 million people live in families in which the head of household or the spouse is in the United States without authorization.[41] Illegal immigrants arriving recently before 2012 tend to be better educated than those who have been in the country a decade or more. A quarter of all immigrants who have arrived in recently before 2012 have at least some college education. Nonetheless, illegal immigrants as a group tend to be less educated than other sections of the U.S. population: 49 percent haven't completed high school, compared with 9 percent of native-born Americans and 25 percent of legal immigrants.[41]

Illegal immigrants work in many sectors of the U.S. economy. Illegal immigrants have lower incomes than both legal immigrants and native-born Americans, but earnings do increase somewhat the longer an individual is in the country.[41]

Breakdown by state[edit]

As of 2014[update],[42] the following data table shows a spread of distribution of locations where illegal immigrants reside by state.

| State of residence | Estimated population in January | Percent of total |

|---|---|---|

| All states | 12,120,000 | 100 |

| California | 2,900,000 | 24 |

| Texas | 1,920,000 | 16 |

| Florida | 760,000 | 6 |

| New York | 640,000 | 5 |

| Illinois | 550,000 | 5 |

| New Jersey | 480,000 | 4 |

| Georgia | 430,000 | 4 |

| North Carolina | 400,000 | 3 |

| Arizona | 370,000 | 3 |

| Washington | 290,000 | 2 |

| Other states | 3,370,000 | 28 |

Population[edit]

From 2005 to 2009, the number of people entering the U.S. illegally declined by nearly 67%, according to the Pew Hispanic Center, from 850,000 yearly average in the early 2000s to 300,000.[43] The most recent estimates put the number of unauthorized immigrants at 11 million in 2015, representing 3.4% of the total U.S. population.[16] The population of unauthorized immigrants peaked in 2007, when it was at 12.2 million and 4% of the total U.S. population.[16][17] As of 2014, unauthorized immigrant adults had lived in the U.S. for a median of 13.6 years, with approximately two-thirds having lived in the U.S. for at least a decade.[16]

US illegal alien apprehensions from US Border Patrol as of 2017.

Narrowing the discussion to only Mexican nationals, a 2015 study performed by demographers of the University of Texas at San Antonio and the University of New Hampshire found that immigration from Mexico; both legal and illegal, peaked in 2003 and that from the period between 2003 and 2007 to the period of 2008 to 2012, immigration from Mexico decreased 57%. The dean of the College of Public Policy of the University of Texas at San Antonio, Rogelio Saenz, states that lower birth rates and the growing economy in Mexico slowed emigration, creating more jobs for Mexicans. Saenz also states that Mexican immigrants are no longer coming to find jobs but to flee from violence, noting that the majority of those escaping crime "are far more likely to be naturalized U.S. citizens".[44]

According to a 2017 National Bureau of Economic Research paper, "The number of undocumented immigrants has declined in absolute terms, while the overall population of low-skilled, foreign-born workers has remained stable. ... because major source countries for U.S. immigration are now seeing and will continue to see weak growth of the labor supply relative to the United States, future immigration rates of young, low-skilled workers appear unlikely to rebound, whether or not U.S. immigration policies tighten further."[45]

Children[edit]

The Pew Hispanic Center determined that according to an analysis of Census Bureau data about 8 percent of children born in the United States in 2008—about 340,000—were offspring of illegal immigrants. (The report classifies a child as offspring of illegal immigrants if either parent is unauthorized.) In total, 4 million U.S.-born children of illegal immigrant parents resided in this country in 2009 (alongside 1.1 million foreign-born children of illegal immigrant parents).[46] These infants are, according to the longstanding administrative interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, American citizens from birth. Congress has never legislated, nor the Supreme Court specifically ruled on whether babies born to visiting foreign nationals are eligible for automatic US Citizenship. These children are sometimes referred to as anchor babies because of the belief that the mother gave birth in the United States as a way to anchor their family in the US.[47]

2011–2016 surge in unaccompanied minors from Central America[edit]

Over the period 2011-2016, U.S. Border Patrol apprehended 178,825 unaccompanied minors from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.[48] The provisions of the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008, which specifies safe repatriation of unaccompanied children (other than those trafficked for sex or forced labor) from countries which do not have a common border with the United States, such as the nations of Central America other than Mexico, made expeditious deportation of the large number of children from Central America who came to the United States in 2014 difficult and expensive, prompting a call by President Barack Obama for an emergency appropriation of $4 billion[49] and resulting in discussions by the Department of Justice and Congress of how to interpret or revise the law in order to expedite handling large numbers of children under the act.[50]

A 2016 study found that Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which allows unauthorized immigrants who migrated to the United States before their 16th birthday and prior to June 2007 to temporarily stay, did not significantly impact the number of apprehensions of unaccompanied minors from Central America.[51] Rather, "the 2008 Williams Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act, along with violence in the originating countries and economic conditions in both the countries of origin and the United States, emerge as some of the key determinants of the recent surge in unaccompanied minors apprehended along the southwest US-Mexico border."[51] According to a 2015 report by the Government Accountability Office, the primary drivers of the surge "were crime and lack of economic opportunity at home. Other reasons included education concerns, desire to rejoin family and aggressive recruiting by smugglers."[52] A 2017 Center for Global Development study stated that violence was the primary driver behind the surge in unaccompanied Central American minors to the United States: an additional 10 homicides in Central America made 6 unaccompanied children flee to the US.[53]

2018 zero tolerance policy[edit]

In April 2018 the then-attorney general of the Trump administration, Jeff Sessions, announced a zero tolerance policy regarding asylum seekers crossing the US southern border without a visa. Asylum seekers and their families who turned themselves in to Border Control agents were charged with criminal entry. If the asylum seekers had children, the children were removed from their parent's custody and placed in detention centers.[54] As of June 2018[update], "thousands of children [have been] detained in makeshift shelters."[55] There was widespread condemnation of this policy including that of notable evangelical Christian leaders such as Franklin Graham.[56]

Countries of origin[edit]

According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the countries of origin for the largest numbers of illegal immigrants are as follows (latest of 2017):[42]

| Country of origin | Raw number | Percent of total |

|---|---|---|

Mexico | 6,640,000 | 55 |

El Salvador | 700,000 | 6 |

Guatemala | 640,000 | 5 |

India | 430,000 | 4 |

Honduras | 400,000 | 3 |

Philippines | 360,000 | 3 |

China | 270,000 | 2 |

Korea | 250,000 | 2 |

Vietnam | 200,000 | 2 |

Dominican Republic | 180,000 | 1 |

| Other | 2,050,000 | 17 |

According to the Migration Policy Institute, Mexicans represented 53% of the undocumented population.[57]

The Urban Institute also estimates "between 65,000 and 75,000 Canadians currently live illegally in the United States."[58]

Trends[edit]

Both the population of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. and southwestern border apprehensions have declined significantly over the past decade.[59][60]

In 2017, illegal border crossing arrests hit a 46-year low, and were down 25% from the previous year.[61] NPR stated that immigrants may be less likely to attempt to enter the U.S. illegally because of President Trump's stance on illegal immigration.[62][63] The majority of undocumented immigrants come from Mexico. Studies have shown that 40 million foreign born residents live in the US. 11.7 million of that population is undocumented.[64] During the 1950s, there were 45,000 documented immigrants from Central America. In the 1960s, this number more than doubled to 100,000. In the decade after, it increased to 134,000.[65]

Illegal entry[edit]

The Pew Hispanic Center estimated that 6–7 million immigrants came to the United States via illegal entry (the rest entering via legal visas allowing a limited stay, but then not leaving when their visa period ended).[29] There are an estimated half million illegal entries into the United States each year.[29][66] Illegal border crossings have declined considerably from 2000, when 71,000–220,000 migrants were apprehended each month, to 2018 when 20,000–40,000 migrants were apprehended.[23]

A common means of border crossing is to hire people smugglers to help them across the border. Those operating on the U.S.-Mexico border are known informally as coyotajes (coyotes).[66] Criminal gangs smuggling illegal immigrants from China are known as snakeheads, and charge as much as US$70,000 per person, which immigrants often promise to pay with money they hope to earn in the United States.[67][68]

Visa overstay[edit]

According to Pew, between 4 and 5.5 million foreigners entered the United States with a legal visa, accounting for between 33–50% of the total population.[29] A tourist or traveler is considered a "visa overstay" once he or she remains in the United States after the time of admission has expired. The time of admission varies greatly from traveler to traveler depending on the visa class into which they were admitted. Visa overstays tend to be somewhat more educated and better off financially than those who entered the country illegally.[69]

To help track visa overstayers the US-VISIT (United States Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology) program collects and retains biographic, travel, and biometric information, such as photographs and fingerprints, of foreign nationals seeking entry into the United States. It also requires electronic readable passports containing this information.

Visa overstayers mostly enter with tourist or business visas.[29] In 1994, more than half[70] of illegal immigrants were Visa overstayers whereas in 2006, about 45% of illegal immigrants were Visa overstayers.[71]

Those who leave the United States after overstaying their visa for more than 180 days but less than one year, leave and then attempt to apply for readmission will face a three-year ban which will not allow them to re-enter the U.S. for that period. Those who leave the United States after overstaying their visa for a period of one year or longer, leave and then attempt to apply for readmission will face a ten-year ban.[72]

Border Crossing Card violation[edit]

A smaller number of illegal immigrants entered the United States legally using the Border Crossing Card, a card that authorizes border crossings into the U.S. for a set amount of time. Border Crossing Card entry accounts for the vast majority of all registered non-immigrant entry into the United States—148 million out of 179 million total—but there is little hard data as to how much of the illegal immigrant population entered in this way. The Pew Hispanic Center estimates the number at around 250,000–500,000.[29]

In the workforce[edit]

Illegal immigrants within the workforce are extremely vulnerable due to their status. Being undocumented makes these individuals susceptible to exploitation by American employers as they are more willing to work through bad conditions and low income jobs — consequently making themselves vulnerable to abuse.[73] Most undocumented migrants end up being hired by U.S. employers who exploit the low-wage market produced through immigration. Typical jobs include: janitorial services, clothing production, and household work.[73]

Many undocumented Latin American immigrants are inclined to the labor market because of the constraints they have with their job opportunities. This consequently forms an informal sector within the labor market. As a result, this attachment formulates an ethnic identity for this sector.[73]

Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) in 1996. This prevented federal, state, and local public benefits from flowing to undocumented immigrants. It also required federal and state agencies to disclose if someone was undocumented. Additionally, PRWORA prohibited states from giving professional licenses to those undocumented.[74] Though PRWORA prevents public benefits from flowing to undocumented immigrants, there are exceptions. Undocumented immigrants are still entitled to medical assistance, immunizations, disaster relief, and k-12 education. Despite this, federal law still requires local and state governments to deny benefits to those undocumented.[74] The implementation of PRWORA demonstrated the shift towards personal responsibility over "public dependency."[75] There were about eight million undocumented workers in the United States in 2010. These workers were 5% of America's workforce.[74]

Organized migrant caravans[edit]

For several years, Pueblo Sin Fronteras, which means "People Without Borders" has organized an annual part-protest, part-mass migration march, from Honduras, through Mexico, to the United States border, where asylum in the United States is requested.[76] In April 2018, the annual "Stations of the Cross Caravan" saw 1,000 Central Americans trying to reach the United States, prompting President Trump to deem it a threat to national security and announce plans to send the national guard to protect the US border.[77] In October 2018, a second caravan of the year left the city of San Pedro Sula the day after US vice-president, Mike Pence, urged the presidents of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala to persuade their citizens to stay home.[78]

Causes[edit]

There are however numerous incentives which draw foreigners to the US. Most illegal immigrants who come to America come for better opportunities for employment, a greater degree of freedom, avoidance of political oppression, freedom from violence, famine, and family reunification.[79][80][53][81][82]

International polls by the Gallup organization from 2013 to 2016 in 156 foreign countries found that about 147 million adults would, if they could, move to the US, making it the most-desired destination country for potential migrants worldwide, followed by Germany and Canada.[83]

Causes by region[edit]

In general, illegal immigrants from Mexico and Central America come for economic reasons, but also sometimes due to political oppression.[79][better source needed] From Asia, they come for economic reasons but some come involuntarily as indentured servants or sex slaves.[79][better source needed] From Sub-Saharan Africa, they come for economic activities and there is some chance of slave trade.[79][better source needed] From Eastern Europe, they come for economic activities and to rejoin family already in the United States. However, there are also some who come involuntarily who work in the sex industry.[79][better source needed]

Economic incentives[edit]

Economic reasons are one motivation for people to illegally immigrate to the United States.[84][85] United States employers hire illegal immigrants at wages substantially higher than they could earn in their native countries.[84] A study of illegal immigrants from Mexico in the 1978 harvest season in Oregon showed that they earned six times what they could have earned in Mexico, and even after deducting the costs of the seasonal migration and the additional expense of living in the United States, their net U.S. earnings were three times their Mexican alternative.[85] In the 1960s and early 70s, Mexico's high fertility rate caused a large increase in population. While Mexican population growth has slowed, the large numbers of people born in the 1960s and 70s are now of working age looking for jobs.[85]

According to Judith Gans of the University of Arizona, United States employers are pushed to hire illegal immigrants for three main reasons:[84]

- Global economic change. Global economic change is one cause for illegal immigration because information and transportation technologies now foster internationalized production, distribution and consumption, and labor. This has encouraged many countries to open their economies to outside investment, then increasing the number of low-skilled workers participating in global labor markets and making low-skilled labor markets all more competitive. This and the fact that developed countries have shifted from manufacturing to knowledge-based economies, have realigned economic activity around the world. Labor has become more international as individuals immigrate seeking work, despite governmental attempts to control this migration. Because the United States education system creates relatively few people who either lack a high school diploma or who hold PhDs, there is a shortage of workers needed to fulfill seasonal low-skilled jobs as well as certain high-skilled jobs. To fill these gaps, the United States immigration system attempts to compensate for these shortages by providing for temporary immigration by farm workers and seasonal low-skilled workers, and for permanent immigration by high-skilled workers.

- A lack of legal immigration channels.

- The ineffectiveness of current employer sanctions for illegal hiring. This allows immigrants who are in the country illegally to easily find jobs. There are three reasons for this ineffectiveness—the absence of reliable mechanisms for verifying employment eligibility, inadequate funding of interior immigration enforcement, and the absence of political will due to labor needs to the United States economy. For example, it is unlawful to knowingly hire an illegal immigrant, but according to Judith Gans, there are no reliable mechanisms in place for employers to verify that the immigrants' papers are authentic.

Another reason for the large numbers of illegal immigrants present in the United States is the termination of the bracero program. This bi-national program between the U.S. and Mexico existed from 1942 to 1964 to supply qualified Mexican laborers as guest workers to harvest fruits and vegetables in the United States. During World War II, the program benefited the U.S. war effort by replacing citizens' labor in agriculture to serve as soldiers overseas. The program was designed to provide legal flows of qualified laborers to the U.S. Many Mexicans deemed unqualified for the program nonetheless immigrated illegally to the United States to work. In doing that they broke both U.S. and Mexican law.[86] Many legal temporary workers became illegal when they chose to continue working in the U.S. after this program ended. The change in law was not accompanied by a change in economic incentives for Mexican workers and the American growers.[85]

Channels for legal immigration[edit]

The United States immigration system provides channels for legal, permanent economic immigration, especially for high-skilled workers. For low-skilled workers, temporary or seasonal legal immigration is easier to acquire.[84] The United States immigration system rests on three pillars: family reunification, provision of scarce labor (as in agricultural and specific high-skilled worker sectors), and protecting American workers from competition with foreign workers.[84] The current system sets an overall limit of 675,000 permanent immigrants each year; this limit does not apply to spouses, unmarried minor children or parents of U.S. citizens.[87] Outside of this number for permanent immigrants, 480,000 visas are allotted for those under the family-preference rules and 140,000 are allocated for employment-related preferences.[87] The current system and low number of visas available make it difficult for low-skilled workers to legally and permanently enter the country to work, so illegal entry becomes the way immigrants respond to the lure of jobs with higher wages than what they would be able to find in their current country.[84]

Family reunification[edit]

According to demographer Jeffery Passel of the Pew Hispanic Center, the flow of Mexicans to the U.S. has produced a "network effect"—furthering immigration as Mexicans moved to join relatives already in the U.S.[88]

Further incentives[edit]

Lower costs of transportation, communication and information has facilitated illegal immigration. Mexican nationals, in particular, have a very low financial cost of immigration and can easily cross the border. Even if it requires more than one attempt, they have a very low probability of being detected and then deported once they have entered the country.[85]

International controversies[edit]

Mexican federal and state government assistance[edit]

The US Department of Homeland Security and some advocacy groups have criticized a program of the government of the state of Yucatán and that of a federal Mexican agency directed to Mexicans migrating to and residing in the United States. They state that the assistance includes advice on how to get across the U.S. border illegally, where to find healthcare, enroll their children in public schools, and send money to Mexico. The Mexican federal government also issues identity cards to Mexicans living outside of Mexico.[89]

- In 2005, the government of Yucatán produced a handbook and DVD about the risks and implications of crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. The guide told immigrants where to find health care, how to get their kids into U.S. schools, and how to send money home. Officials in Yucatán said the guide is a necessity to save lives but some American groups accused the government of encouraging illegal immigration.[90]

- In 2005, the Mexican government was criticized for distributing a comic book which offers tips to illegal emigrants to the United States.[91] That comic book recommends to illegal immigrants, once they have safely crossed the border, "Don't call attention to yourself. ... Avoid loud parties. ... Don't become involved in fights." The Mexican government defends the guide as an attempt to save lives. "It's kind of like illegal immigration for dummies," said the executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies in Washington, Mark Krikorian. "Promoting safe illegal immigration is not the same as arguing against it". The comic book does state on its last page that the Mexican Government does not promote illegal crossing at all and only encourages visits to the US with all required documentation.[91]

Legal issues[edit]

Department of Homeland Security's report of number of illegal immigrants removed or returned, numbers through 2016.[92]

Aliens can be classified as unlawfully present for one of three reasons: entering without authorization or inspection, staying beyond the authorized period after legal entry, or violating the terms of legal entry.[93]

Improper entry[edit]

Section 1325 in Title 8 of the United States Code, "Improper entry of alien", provides for a fine, imprisonment, or both for any non-citizen who:[94]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

- enters or attempts to enter the United States at any time or place other than as designated by immigration agents, or

- eludes examination or inspection by immigration agents, or

- attempts to enter or obtains entry to the United States by a willfully false or misleading representation or the willful concealment of a material fact.

The maximum prison term is 6 months for the first offense with a misdemeanor and 2 years for any subsequent offense with a felony. In addition to the above criminal fines and penalties, civil fines may also be imposed.

Visa overstay[edit]

Aliens entering the country legally and overstaying their visas for less than 180 days are (beyond deportation) subject only to the civil penalty of being restricted as to where they can apply for another US visa.[95] Since 2007, visa overstays have accounted for a larger share of the growth in the undocumented immigrant population than illegal border crossings.[22]

Unlawful residence[edit]

Those "unlawfully present" in the US for more than 180 consecutive days but less than a year, because of visa overstay or any other reason, are subject to the civil penalty of being barred from readmission to the US for three years; those overstaying for more than a year are barred from readmission to the US for ten years.[95]

Arizona passed immigration enforcement law Arizona SB 1070 in April 2010, which was at the time the "toughest bill on illegal immigration" in the United States,[96] and was challenged by the Department of Justice as encroaching on powers reserved by the United States Constitution to the Federal Government.[96] On July 28, 2010, United States District Court Judge Susan Bolton issued a preliminary injunction affecting the most controversial parts of the law, including the section that required police officers to check a person's immigration status after a person had been involved in another act or situation which resulted in police activity.[97] In 2016, Arizona reached a settlement with a number of immigrants rights organizations, including the National Immigration Law Center, overturning this aspect of the bill. The practice had led to racial profiling of Latinos and other minorities.[98]

Employment[edit]

During the Nannygate scandal, the Clinton administration reviewed hiring practices for over a thousand presidential appointments after it became known that certain candidates for office had employed illegal immigrants as domestic helpers.

Audits of employment records in 2009 at American Apparel, a prominent Los Angeles garment manufacturer, by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency uncovered discrepancies in the documentation of about 25 percent of the company's workers. This technique of auditing employment records originated during the George W. Bush presidency and has been continued under President Barack Obama. It may result in deportations should definite evidence of illegality be uncovered, but at American Apparel the audit resulted only in the termination of employees who could not resolve discrepancies. Most fired workers, some of whom had worked a decade at the plant, reported that they would seek other employment within the United States.[citation needed] This technique of enforcement is much less disruptive than mass raids at workplaces.

The neutrality of this section is disputed. (September 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Illegal immigrants are generally not allowed to receive state or local public benefits, which includes professional licenses.[99] However, in 2013 the California State Legislature passed laws allowing illegal immigrants to obtain professional licenses. On February 1, 2014. Sergio C. Garcia became the first illegal immigrant to be admitted to the State Bar of California since 2008, when applicants were first required to list citizenship status on bar applications.[100]

Apprehension[edit]

Federal law enforcement agencies, specifically U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the United States Border Patrol (USBP), and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), enforce the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (INA), and to some extent, the United States Armed Forces, state and local law enforcement agencies, and civilians and civilian groups guard the border.

At workplace[edit]

Before 2007, immigration authorities alerted employers of mismatches between reported employees' Social Security cards and the actual names of the card holders. In September 2007, a federal judge halted this practice of alerting employers of card mismatches.[101]

At times illegal hiring has not been prosecuted aggressively: between 1999 and 2003, according to The Washington Post, "work-site enforcement operations were scaled back 95 percent by the Immigration and Naturalization Service.[102] Major employers of illegal immigrants have included:

Wal-Mart: In 2005, Wal-Mart agreed to pay $11 million to settle a federal investigation that found hundreds of illegal immigrants were hired by Wal-Mart's cleaning contractors.[103]

Swift & Co.: In December 2006, in the largest such crackdown in American history, U.S. federal immigration authorities raided Swift & Co. meat-processing plants in six U.S. states, arresting about 1,300 illegal immigrant employees.[104]

Tyson Foods: This company was accused of actively importing illegal labor for its chicken packing plants; at trial, however, the jury acquitted the company after evidence was presented that Tyson went beyond mandated government requirements in demanding documentation for its employees.[105]- Gebbers Farms: In December 2009, U.S. immigration authorities forced this Brewster, Washington, farm known for its fruit orchards to fire more than 500 illegal workers, mostly immigrants from Mexico. Some were working with false social security cards and other false identification.[106]

El Paso (top) and Ciudad Juárez (bottom) seen from earth orbit; the Rio Grande is the thin line separating the two cities through the middle of the photograph.

Detention[edit]

About 31,000 people who are not American citizens are held in immigration detention on any given day,[107] including children, in over 200 detention centers, jails, and prisons nationwide.[108] The United States government held more than 300,000 people in immigration detention in 2007 while deciding whether to deport them.[109]

Deportation[edit]

Deportations of immigrants, which are also referred to as removals, may be issued when immigrants are found to be in violation of US immigration laws. Deportations may be imposed on a person who is neither native-born nor a naturalized citizen of the United States.[110]

Deportation proceedings are also referred to as removal proceedings and are typically initiated by the Department of Homeland Security. The United States issues deportations for various reasons which include security, protection of resources, and protection of jobs.

Deportations from the United States increased by more than 60 percent from 2003 to 2008, with Mexicans accounting for nearly two-thirds of those deported.[111] Under the Obama administration, deportations have increased to record levels beyond the level reached by the George W. Bush administration with a projected 400,000 deportations in 2010, 10 percent above the deportation rate of 2008 and 25 percent above 2007.[112]Fiscal year 2011 saw 396,906 deportations, the largest number in the history of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; of those, about 55% had been convicted of crimes or misdemeanors, including:[113]

- 44,653 convicted of drug-related crimes

- 35,927 convicted of driving under the influence

- 5,848 convicted of sexual offenses

- 1,119 convicted of homicide

By the end of 2012, as many people had been deported during the first four years of the Obama presidency as were deported during the eight-year presidency of George W. Bush;[114] the number of deportations under Obama totalled 2.5 million by the end of 2015.[115]

The AEDPA and IIRIRA Acts of 1996[edit]

Two major pieces of legislation passed in 1996 had a significant effect on illegal immigration and deportations in the United States; the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA). These were introduced following the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, both of which were terrorist attacks that claimed American lives. These two acts changed the way criminal cases of lawful permanent residents were handled, resulting in increased deportations from the United States.[116] Before the 1996 deportation laws, there were two steps that lawful permanent noncitizen residents who were convicted of crimes went through. The first step determined whether or not the person was deportable. The second step determined if that person should or shouldn't be deported. Before the 1996 deportation laws, the second step prevented many permanent residents from being deported by allowing for their cases to be reviewed in full before issuing deportations. External factors were taken into consideration such as the effect deportation would have on a person's family members and a person's connections with their country of origin. Under this system permanent residents were able to be relieved of deportation if their situation deemed it unnecessary. The 1996 laws however issued many deportations under the first step, without going through the second step, resulting in a great increase in deportations.[citation needed]

One significant change that resulted from the new laws was the definition of the term aggravated felony. Being convicted of a crime that is categorized as an aggravated felony results in mandatory detention and deportation. The new definition of aggravated felony includes crimes such as shoplifting, which would be a misdemeanor in many states. The new laws have categorized a much wider range of crimes as aggravated felonies. The effect of this has been a large increase in permanent residents facing mandatory deportation from the United States without the opportunity to plea for relief. The 1996 deportation laws have received a lot of criticism for their curtailing of residents' rights.[116]

The USA Patriot Act[edit]

The USA Patriot Act was passed seven weeks after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The purpose of the act was to give the government more power to act upon suspicion of terrorist activity. The new governmental powers granted by this act included a significant expansion of the conditions in which illegal immigrants could be deported based on suspicion of terrorist activity. The act gave the government the power to deport individuals based not only on plots or acts of terrorism, but on affiliations with certain organizations. The Secretary of State designated specific organizations foreign terrorist organizations before the USA Patriot Act was implemented. Organizations on this list were deemed dangerous because they were actively involved in terrorist activity. The Patriot Act created a type of organization called designated organizations. The Secretary of State and Attorney General were given the power to designate any organization that supported terrorist activity on any level. The act also allows for deportation based on involvement in undesignated organizations that were deemed suspicious.[117]

Under the USA Patriot Act the Attorney General was granted the power to "certify" illegal immigrants that pose a threat to national security. Once an illegal immigrant is certified they must be taken into custody and face mandatory detention which will result in a criminal charge or release. The Patriot Act has been criticized for violating the Fifth Amendment right to due process. Under the Patriot Act, an illegal immigrant is not granted the opportunity for a hearing before given certification.[118]

Complications of birthright citizen children and illegal immigrant parents[edit]

Complications in deportation efforts ensue when parents are illegal immigrants but their children are birthright citizens. Federal appellate courts have upheld the refusal by the Immigration and Naturalization Service to stay the deportation of illegal immigrants merely on the grounds that they have U.S.-citizen, minor children.[119] As of 2005, there were some 3.1 million United States citizen children living in families in which the head of the family or a spouse was unauthorized;[120] at least 13,000 children had one or both parents deported in the years 2005–2007.[120][not in citation given]

DREAM Act[edit]

The DREAM Act (acronym for Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) was an American legislative proposal for a multi-phase process for illegal immigrants in the United States that would first grant conditional residency and upon meeting further qualifications, permanent residency. The bill was first introduced in the Senate on August 1, 2001 and has since been reintroduced several times but did not pass. It was intended to stop the deportation of people who had arrived as children and had grown up in the U.S. The Act would give lawful permanent residency under certain conditions which include: good moral character, enrollment in a secondary or post-secondary education program, and having lived in the United States at least 5 years. Those in opposition of the DREAM Act believe that it encourages illegal immigration.[121]

Although the DREAM Act has not been enacted by federal legislation, a number of its provisions were implemented by a memorandum issued by Janet Napolitano of the Department of Homeland Security during the Obama administration. To be eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), one must show that they were under 31 years of age as of June 15, 2012[update]; that they came to the United States before their 16th birthday; that they have continuously resided in the United States from June 15, 2007, until the present; that they were physically present in the United States on June 15, 2012, and at the time they applied for DACA; that they were not authorized to be in the United States on June 15, 2012; that they are currently in school, have graduated or obtained a certificate of completion from high school, have obtained a general education development (GED) certificate, or are an honorably discharged veteran of the Coast Guard or Armed Forces of the United States; and that they have not been convicted of a felony, significant misdemeanor, three or more other misdemeanors, and do not otherwise pose a threat to national security or public safety.[122]

Deportation trends[edit]

United States immigration enforcement actions, 1995–2015[clarification needed]

There have been two major periods of mass deportations in U.S. history. In the Mexican Repatriation of the 1930s, through mass deportations and forced migration, an estimated 500,000 Mexicans and Mexican Americans were deported or coerced into emigrating, in what Mae Ngai, an immigration historian at the University of Chicago, has described as "a racial removal program".[123] The majority of those removed were U.S. citizens.[123] Rep. Luis Gutierrez, D-Ill., cosponsor of a U.S. House Bill that calls for a commission to study the "deportation and coerced emigration" of U.S. citizens and legal residents, has expressed concerns that history could repeat itself, and that should illegal immigration be made into a felony, this could prompt a "massive deportation of U.S. citizens".[123]

In Operation Wetback in 1954, the United States and the Mexican governments cooperated to deport illegal immigrant Mexicans in the U.S. to Mexico. This cooperation was part of more harmonious Mexico-United States relations starting in World War II. Joint border policing operations were established in the 1940s when the Bracero Program (1942–1964) brought qualified Mexicans to the U.S. as guest workers. Many Mexicans who did not qualify for the program migrated illegally. According to Mexican law, Mexican workers needed authorization to accept employment in the U.S. As Mexico industrialized post-World War II in what was called the Mexican Miracle, Mexico wanted to preserve "one of its greatest natural resources, a cheap and flexible labor supply."[124] In some cases along with their U.S. born children (who are citizens according to U.S. law),[125] some illegal immigrants, fearful of potential violence as police swarmed through Mexican American barrios throughout the southeastern states, stopping "Mexican-looking" citizens on the street and asking for identification, fled to Mexico.[125]

In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act that gave amnesty to 3 million illegal immigrants in the country.[126]

A direct effect of the deportation laws of 1996 and the Patriot Act has been a dramatic increase in deportations. Prior to these acts deportations had remained at about an average of 20,000 per year. Between 1990 and 1995 deportations had increased to about an average of 40,000 a year. From 1996 to 2005 the yearly average had increased to over 180,000. In the year 2005 the number of deportations reached 208,521 with less than half being deported under criminal grounds.[127] According to a June 2013 report published by the Washington Office on Latin America, dangerous deportation practices are on the rise and pose a serious threat to the safety of the migrants being deported. These practices include repatriating migrants to border cities with high levels of drug-related violence and criminal activity, night deportations (approximately 1 in 5 migrants reports being deported between the hours of 10 pm and 5 am), and "lateral repatriations", or the practice of moving migrants from the region where they were detained to areas hundreds of miles away.[128] These practices increase the risk of gangs and organized criminal groups preying upon the newly arrived migrants.

In 2013, deportation prioritization guidance used by Immigration and Customs enforcement, was extended to Customs and Border Protection, under the Obama Administration's prosecutorial discretion plan.[129] This has led to a reduction of the number of deportations of those who are in "non-priority" categories.[130]

According to survey by the Associated Press conducted in August 2014, The Homeland Security Department was on pace to remove the fewest number of immigrants since 2007. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the federal agency responsible for deportations, sent home 258,608 immigrants between the start of the budget year—October 1, 2013. and July 28, 2014—a decrease of nearly 20 percent from the same period in 2013, when 320,167 people were removed. Obama announced earlier in 2014 plans to slow down deportations; recently these were put on hold until the November 2014 election.[131]

A study by the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, estimated that the cost of forcibly removing most of the nation's estimated 10 million illegal immigrants is $41 billion a year.[132]

Military involvement[edit]

In 1995, the United States Congress considered an exemption from the Posse Comitatus Act, which generally prohibits direct participation of U.S. soldiers and airmen (and sailors and Marines by policy of the Department of the Navy) in domestic law enforcement activities, such as search, seizure, and arrests.[133]

In 1997, Marines shot and killed 18-year-old U.S. citizen Esequiel Hernández Jr[134] while on a mission to interdict smuggling and illegal immigration near the border community of Redford, Texas. The Marines observed the high school student from concealment while he was tending his family's goats in the vicinity of their ranch. At one point, Hernandez raised his .22-caliber rifle and fired shots in the direction of the concealed soldiers. He was subsequently tracked for 20 minutes then shot and killed.[135][136] In reference to the incident, military lawyer Craig T. Trebilcock argues, "the fact that armed military troops were placed in a position with the mere possibility that they would have to use force to subdue civilian criminal activity reflects a significant policy shift by the executive branch away from the posse comitatus doctrine."[137] The killing of Hernandez led to a congressional review[138] and an end to a nine-year-old policy of the military aiding the Border Patrol.[139]

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the United States again considered placing soldiers along the U.S.–Mexico border as a security measure.[140] In May 2006, President George W. Bush announced plans to use the National Guard to strengthen enforcement of the US-Mexico Border from illegal immigrants,[141] emphasizing that Guard units "will not be involved in direct law enforcement activities".[142] Mexican Foreign Secretary Luis Ernesto Derbez said in an interview with a Mexico City radio station, "If we see the National Guard starting to directly participate in detaining people ... we would immediately start filing lawsuits through our consulates."[143]

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) called on the President not to deploy troops to deter illegal immigrants, and stated that a "deployment of National Guard troops violates the spirit of the Posse Comitatus Act".[144] According to the State of the Union address in January 2007,[145] more than 6,000 National Guard members have been sent to the border to supplement the Border Patrol,[146] costing in excess of $750 million.[147]

Sanctuary cities[edit]

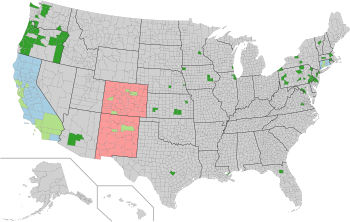

State has legislation in place that establishes a statewide sanctuary for illegal immigrants

County or county equivalent either contains a municipality that is a sanctuary for illegal immigrants, or is one itself

All county jails in the state do not honor ICE detainers

Alongside statewide legislation or policies establishing sanctuary for illegal immigrants, county contains a municipality that has policy or has taken action to further provide sanctuary to illegal immigrants

Several U.S. cities have instructed their own law enforcement personnel and civilian employees not to notify the federal government when they become aware of illegal immigrants living within their jurisdiction.

There is no official definition of "sanctuary city".[148] Cities which have been referred to as "sanctuary cities" by various politicians include Washington, D.C.; New York City; Los Angeles; Chicago; San Francisco;[149]San Diego; Austin; Salt Lake City; Dallas; Detroit; Honolulu; Houston; Jersey City; Minneapolis; Miami; Denver; Aurora, Colorado; Baltimore; Seattle; Portland, Oregon; Portland, Maine; and Senath, Missouri, have become "sanctuary cities", having adopted ordinances refraining from stopping or questioning individuals for the sole purpose of determining their immigration status.[150][151][clarification needed] Most of these ordinances are in place at the state and county, not city, level. These policies do not prevent the local authorities from investigating crimes committed by illegal immigrants.[148]

Attacks on immigrants[edit]

According to a 2006 report by the Anti-Defamation League, white supremacists and other extremists were engaging in a growing number of assaults against legal and illegal immigrants and those perceived to be immigrants.[152][needs update] including assault on migrants from Latin America.

Community-based involvement[edit]

The No More Deaths organization offers food, water, and medical aid to migrants crossing the desert regions of the American Southwest in an effort to reduce the increasing number of deaths along the border.[153]

In 2014, 'Dreamer Moms' began protesting, hoping that President Obama will grant them legal status. On November 12, 2014, there was a hunger strike near the White House undertaken by the group Dreamer Moms. On November 21, 2014, Obama provided 5 million undocumented immigrants legal status because he said that mass deportation "would be both impossible and contrary to our character." However, this decision was challenged in court during the Trump administration and then overturned.[154]

Economic impact[edit]

Illegal immigrants increase the size of the U.S. economy and contribute to economic growth.[17] Illegal immigrants contribute to lower prices of US-produced goods and services, which benefits consumers.[17]

Economists estimate that legalization of the current unauthorized immigrant population would increase the immigrants' earnings[6][7][8][155][17] and consumption considerably.[9] A 2016 National Bureau of Economic Research paper found that "legalization would increase the economic contribution of the unauthorized population by about 20%, to 3.6% of private-sector GDP."[156] Legalization is also likely to reduce untaxed labor in the informal economy.[17] A 2016 study found that Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which allows unauthorized immigrants who migrated to the United States as minors to temporarily stay, increases labor force participation, decreases the unemployment rate and increases the income for DACA-eligible immigrants.[157] The study estimated that DACA moved 50,000 to 75,000 unauthorized immigrants into employment.[157] Another 2016 study found that DACA-eligible households were 38% less likely than non-eligible unauthorized immigrant households to live in poverty.[158]

A 2017 study in the Journal of Public Economics found that more intense immigration enforcement increased the likelihood that US-born children with undocumented immigrant parents would live in poverty.[159]

Native welfare[edit]

A number of studies have shown that illegal immigration increases the welfare of natives.[160][4][5] A 2015 study found that " increasing deportation rates and tightening border control weakens low-skilled labor markets, increasing unemployment of native low-skilled workers. Legalization, instead, decreases the unemployment rate of low-skilled natives and increases income per native."[161] A study by economist Giovanni Peri concluded that between 1990 and 2004, immigrant workers raised the wages of native born workers in general by 4%, while more recent immigrants suppressed wages of previous immigrants.[162]

In a 2017 literature review by the National Academy of Sciences, they explain the positive impact of illegal immigrants on natives in the following way:[17]

The entry of new workers through migration increases the likelihood of filling a vacant position quickly and thus reduces the net cost of posting new offers. The fact that immigrants in each skill category earn less than natives reinforces this effect. Though immigrants compete with natives for these additional jobs, the overall number of new positions employers choose to create is larger than the number of additional entrants to the labor market. The effect is to lower the unemployment rate and to strengthen the bargaining position of workers.

According to Georgetown University economist Anna Maria Mayda and University of California, Davis economist Giovanni Peri, "deportation of undocumented immigrants not only threatens the day-to-day life of several million people, it also undermines the economic viability of entire sectors of the US economy." Research shows that illegal immigrants complement and extend middle- and high-skilled American workers, making it possible for those sectors to employ more Americans. Without access to illegal immigrants, U.S. firms would be incentivized to offshore jobs and import foreign-produced goods. Several highly competitive sectors that depend disproportionately on illegal immigrant labor, such as agriculture, would dramatically shrink and sectors, such as hospitality and food services, would see higher prices for consumers. Regions and cities that have large illegal populations are also likely to see harms to the local economy were the illegal immigrant population removed. While Mayda and Peri note that some low-skilled American workers would see marginal gains, it is likely that the effects on net job creation and wages would be negative for the U.S. as a whole.[163][3]

A 2002 study of the effects of illegal immigration and border enforcement on wages in border communities from 1990 to 1997 found little impact of border enforcement on wages in U.S. border cities, and concluded that their findings were consistent with two hypotheses, "border enforcement has a minimal impact on illegal immigration, and illegal immigration from Mexico has a minimal impact on wages in U.S. border cities".[164]

According to University of California, San Diego economist Gordon H. Hanson, "there is little evidence that legal immigration is economically preferable to illegal immigration. In fact, illegal immigration responds to market forces in ways that legal immigration does not. Illegal migrants tend to arrive in larger numbers when the U.S. economy is booming (relative to Mexico and the Central American countries that are the source of most illegal immigration to the United States) and move to regions where job growth is strong. Legal immigration, in contrast, is subject to arbitrary selection criteria and bureaucratic delays, which tend to disassociate legal inflows from U.S. labor-market conditions. Over the last half-century, there appears to be little or no response of legal immigration to the U.S. unemployment rate."[165]

Fiscal effects[edit]

Illegal immigrants are not eligible for most federally-funded safety net programs.[166] Illegal immigrants are barred from receiving benefits from Medicare, non-emergency Medicaid, or the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and the Medicare program; they also cannot participate in health insurance marketplaces or eligible to receive insurance subsidies under the Affordable Care Act.[166] Illegal immigrants contribute up to $12 billion annually to the Social Security Trust Fund, but are not eligible to receive any Social Security benefits.[166] Unless the illegal immigrants transition to legal status, they will not collect these benefits.[166][17] According to a 2007 literature review by the Congressional Budget Office, "Over the past two decades, most efforts to estimate the fiscal impact of immigration in the United States have concluded that, in aggregate and over the long term, tax revenues of all types generated by immigrants—both legal and unauthorized—exceed the cost of the services they use."[2]

While the aggregate fiscal effects are beneficial to the United States, unauthorized immigration has small but net negative fiscal effects on state and local governments.[2] According to the 2017 National Academy of Science report on immigration, one reason for the adverse fiscal impact on state and local governments is that "the federal government reimburses state and local entities a fraction of costs to incarcerate criminal aliens, the remaining costs are borne by local governments."[17]

A paper in the peer-reviewed journal Tax Lawyer from the American Bar Association concluded that illegal immigrants contribute more in taxes than they cost in social services.[167]

A 2016 study found that, over the period 2000–2011, illegal immigrants contributed $2.2 to $3.8 billion more to the Medicare Trust Fund "than they withdrew annually (a total surplus of $35.1 billion). Had unauthorized immigrants neither contributed to nor withdrawn from the Trust Fund during those 11 years, it would become insolvent in 2029—1 year earlier than currently predicted."[168]

Mortgages[edit]

Around 2005, an increasing number of banks saw illegal immigrants as an untapped resource for growing their own revenue stream and contended that providing illegal immigrants with mortgages would help revitalize local communities, with many community banks providing home loans for illegal immigrants. At the time, critics complained that this practice would reward and encourage illegal immigration, as well as contribute to an increase in predatory lending practices. One banking consultant said that banks which were planning to offer mortgages to illegal immigrants were counting on the fact that immigration enforcement was very lax, with deportation unlikely for anyone who had not committed a crime.[169]

Crime and law enforcement[edit]

Relationship between illegal immigration and crime[edit]

According to empirical evidence, immigrants including the illegal ones, are less likely to commit crimes than native-born citizens in the United States.[170][171][172][11][10] For immigration in general, a majority of studies in the U.S. have found lower crime rates among immigrants than among non-immigrants, and that higher concentrations of immigrants are associated with lower crime rates.[173][174][175][176][177][178][179] Some research even suggests that increases in immigration may partially explain the reduction in the U.S. crime rate.[180][181][182][183][184][185] A 2013 study found that children of immigrants were more likely to commit crimes than their parents.[186]

2014 and 2018 studies found that undocumented immigration to the United States did not increase violent crime.[187][188] A 2016 study found no link between illegal immigrant populations and violent crime, although there is a small but significant association between illegal immigrants and drug-related crime.[189] A 2017 study found that "Increased undocumented immigration was significantly associated with reductions in drug arrests, drug overdose deaths, and DUI arrests, net of other factors."[190] A 2017 study found that California's extension of driving licenses to unauthorized immigrants "did not increase the total number of accidents or the occurrence of fatal accidents, but it did reduce the likelihood of hit and run accidents, thereby improving traffic safety and reducing costs for California drivers ... providing unauthorized immigrants with access to driver's licenses can create positive externalities for the communities in which they live."[191] A 2018 study in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy found that by restricting the employment opportunities for unauthorized immigrants, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) likely caused an increase in crime.[192][193] A 2018 PLOS One study estimated that the undocumented immigrant population in the United States was 22 million (approximately twice as large as the estimate derived from U.S. Census Bureau figures); an author of the study notes that this has implications for the relationship between undocumented immigration and crime suggesting the correlation is lower than previously estimated: "You have the same number of crimes but now spread over twice as many people as was believed before, which right away means that the crime rate among undocumented immigrants is essentially half whatever was previously believed."[194]

A 2018 study found no evidence that apprehensions of undocumented immigrants in districts in the United States reduced crime rates.[195]

Impact of immigration enforcement[edit]

Research suggests immigration enforcement deters unauthorized immigration[80] but has no impact on crime rates.[14][15][12][196] Immigration enforcement is costly and may divert resources from other forms of law enforcement.[80][196] Tougher immigration enforcement has been associated with greater migrant deaths, as migrants take riskier routes and use the services of smugglers.[80][197] Tough border enforcement may also encourage unauthorized immigrants to settle in the United States, rather than regularly travel across the border where they may be captured.[80][198] Immigration enforcement programs have been shown to lower employment and wages among unauthorized immigrants, while increasing their participation in the informal economy.[80]

Research finds that Secure Communities, an immigration enforcement program which led to a quarter of a million of detentions (when the study was published; November 2014), had no observable impact on the crime rate.[14] A 2015 study found that the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, which legalized almost 3 million immigrants, led to "decreases in crime of 3-5 percent, primarily due to decline in property crimes, equivalent to 120,000-180,000 fewer violent and property crimes committed each year due to legalization".[15]

A 2017 review study of the existing literature noted that the existing studies had found that sanctuary cities — which adopt policies designed to avoid prosecuting people solely for being an illegal immigrant — either have no impact on crime or that they lower the crime rate.[13] A second 2017 study in the journal Urban Affairs Review found that sanctuary policy itself has no statistically meaningful effect on crime.[199][200][201][202][203] The findings of the study were misinterpreted by Attorney General Jeff Sessions in a July 2017 speech when he claimed that the study showed that sanctuary cities were more prone to crime than cities without sanctuary policies.[204][205] A third study in the journal Justice Quarterly found evidence that the adoption of sanctuary policies reduced the robbery rate but had no impact on the homicide rate except in cities with larger Mexican undocumented immigrant populations which had lower rates of homicide.[206]

According to a study by Tom K. Wong, associate professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego, published by the Center for American Progress, a progressive think tank: "Crime is statistically significantly lower in sanctuary counties compared to nonsanctuary counties. Moreover, economies are stronger in sanctuary counties – from higher median household income, less poverty, and less reliance on public assistance to higher labor force participation, higher employment-to-population ratios, and lower unemployment."[207] The study also concluded that sanctuary cities build trust between local law enforcement and the community, which enhances public safety overall.[208] The study evaluated sanctuary and non-sanctuary cities while controlling for differences in population, the foreign-born percentage of the population, and the percentage of the population that is Latino."[207]

After the Obama administration reduced federal immigration enforcement, Democratic counties reduced their immigration enforcement more than Republican counties; a paper by a University of Pennsylvania PhD candidate found "that Democratic counties with higher non-citizen population shares saw greater increases in clearance rates, a measure of policing efficiency, with no increase in crime rates. The results indicate that reducing immigration enforcement did not increase crime and rather led to an increase in policing efficiency, either because it allowed police to focus efforts on solving more serious crimes or because it elicited greater cooperation of non-citizens with police."[196] A 2003 paper by two Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas economists found "that while the volume of illegal immigration is not related to changes in property-related crime, there is a significant positive correlation with the incidence of violent crime. This is most likely due to extensive smuggling activity along the border. Border enforcement meanwhile is significantly negatively related to crime rates. The bad news is that the deterrent effect of the border patrol diminishes over this time period, and the net impact of more enforcement on border crime since the late 1990s is zero."[209]

According to Cornell University economist Francine Blau and University of California at Berkeley economist Gretchen Donehower, the existing "evidence does not suggest that ... stepping up enforcement of existing immigration laws would generate savings to existing taxpayers."[210] By complicating circular migration and temporary work by migrants, and by incentivizing migrants to settle permanently in the US, the 2017 National Academy of Sciences report on immigration notes that "it is certainly possible that additional costs have been created to the economy by the increased border enforcement, beyond the narrow costs of the programs themselves in the federal budget."[17]

Gang activity[edit]

A US Justice Department report from 2009 indicated that one of the largest transnational criminal organizations in the United States, Los Angeles-based 18th Street gang, has a membership of some 30,000 to 50,000 with 80% of them being illegal immigrants from Mexico and Central America. Active in 44 cities in 20 states, its main source of income is street-level distribution of cocaine and marijuana and, to a lesser extent, heroin and methamphetamine. Gang members also commit assault, auto theft, carjacking, drive-by shootings, extortion, homicide, identification fraud, and robbery.[211]

Identity theft[edit]

Identity theft is sometimes committed by illegal immigrants who use Social Security numbers belonging to others in order to obtain fake work documentation.[212] In 2009, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Flores-Figueroa v. United States that illegal immigrants cannot be prosecuted for identity theft if they use "made-up" Social Security numbers that they do not know belong to someone else; to be guilty of identity theft with regard to social security numbers, they must know that the social security numbers that they use belong to others.[213]

Education[edit]

An estimated 65,000 undocumented youth graduate from high school every year but only 5 to 10 percent go on to college.[citation needed]

Studies have shown that undocumented immigrants are wary of disclosing their immigration status to counselors, teachers and mentors. In other words, undocumented students sometimes did not disclose their status to the very individuals that could help them find pathways to higher education.[214][215]

Harm to illegal immigrants[edit]

There are significant dangers associated with illegal immigration including potential death when crossing the border. According to Chicano activist Roberto Martinez, since the 1994 implementation of an immigration-control effort called Operation Gatekeeper, immigrants have attempted to cross the border in more dangerous locations.[216] Those crossing the border come unprepared, without food, water, proper clothing, or protection from the elements or dangerous animals; sometimes the immigrants are abandoned by those smuggling them.[216] Deaths also occur while resisting arrest. In May 2010, the National Human Rights Commission in Mexico accused Border Patrol agents of tasering illegal immigrant Anastasio Hernández-Rojas to death. Media reports that Hernández-Rojas started a physical altercation with patrol agents and later autopsy findings concluded that the suspect had trace amounts of methamphetamine in his blood levels which contributed to his death.[217][218] The foreign ministry in Mexico City has demanded an explanation from San Diego and federal authorities, according to Tijuana newspapers.[217] According to the U.S. Border Patrol, there were 987 assaults on Border Patrol agents in 2007 and there were a total of 12 people killed by agents in 2007 and 2008.[219]

According to the Washington Office on Latin America's Border Fact Check site, Border Patrol rarely investigates allegations of abuse against migrants, and advocacy organizations say, "even serious incidents such as the shootings of migrants result in administrative, not criminal, investigations and sanctions."[220]

Health[edit]

A 2017 Science study found that Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which allows unauthorized immigrants who migrated to the United States as minors to temporarily stay, led to improved mental health outcomes for the children of DACA-eligible mothers.[221] A 2017 Lancet Public Health study reported found that DACA-eligible individuals had better mental health outcomes as a result of their DACA-eligibility.[222]

Exploitation by employers[edit]

Many Mexican immigrants have been trafficked by either their smugglers or the employers after they have gotten to the United States. According to research at San Diego State University, approximately 6% of illegal Mexican immigrants were trafficked by their smugglers while entering the United States and 28% were trafficked by their employers after entering the United States. Trafficking rates were particularly high in the construction and cleaning industries. They also determined that 55% of illegal Mexican immigrants were abused or exploited by either their smugglers or employers.[223]

Indian, Russian, Thai, Vietnamese and Chinese women have been reportedly brought to the United States under false pretenses. "As many as 50,000 people are illicitly trafficked into the United States annually, according to a 1999 CIA study. Once here, they're forced to work as prostitutes, sweatshop laborers, farmhands, and servants in private homes." US authorities call it "a modern form of slavery".[224][225] Many Latina women have been lured under false pretenses to illegally come to the United States and are instead forced to work as prostitutes catering to the immigrant population. Non-citizen customers without proper documentation that have been detained in prostitution stings are generally deported.[226]

Prostitution[edit]

The Coalition Against Trafficking in Women has reported scores of cases where women were forced to prostitute themselves. "Trafficking in women plagues the United States as much as it does underdeveloped nations. Organized prostitution networks have migrated from metropolitan areas to small cities and suburbs. Women trafficked to the United States have been forced to have sex with 400–500 men to pay off $40,000 in debt for their passage."[227]

Death[edit]

Death by exposure has been reported in the deserts, particularly during the hot summer season.[228] "Exposure to the elements" encompasses hypothermia, dehydration, heat strokes, drowning, and suffocation. Also, illegal immigrants may die or be injured when they attempt to avoid law enforcement. Martinez points out that engaging in high speed pursuits while attempting to escape arrest can lead to death.[229] Many migrants are also killed or maimed riding the roofs of cargo trains in Mexico.[230]

Workplace injury[edit]

Recent studies have found that illegal immigration status is perceived by Latino immigrant workers as a barrier to safety at work.[231][232]

Public opinion and controversy[edit]

United States economy[edit]