Anno II

| Saint Anno of Cologne | |

|---|---|

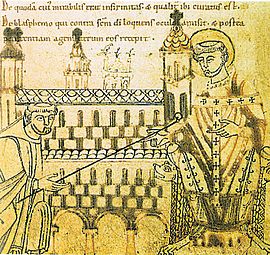

Archbishop Anno instates Erpho, first abbot of Michaelsberg Abbey, 12th century manuscript | |

| Archbishop | |

| Born | c. 1010 Altsteußlingen, Swabia |

| Died | (1075-12-04)4 December 1075 Siegburg |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Canonized | 29 April 1183 by Pope Lucius III |

| Major shrine | Michaelsberg Abbey, Siegburg |

| Feast | 4 December |

Anno II (c. 1010 – 4 December 1075) was Archbishop of Cologne from 1056 until his death. From 1063 to 1065 he acted as regent of the Holy Roman Empire for the minor Emperor Henry IV. Anno is venerated as a saint of the Catholic Church.

Contents

1 Life

2 Veneration

3 See also

4 References

5 Sources

Life

He was born to the edelfrei Steusslingen family at Altsteußlingen (near Ehingen) in Swabia, and was educated in Bamberg,[1] where he subsequently became head of the cathedral school. In 1046 he became chaplain to the Salian emperor Henry III, and accompanied him on his campaigns against KIng Andrew I of Hungary in 1051 and 1052. The emperor appointed him provost at the newly erected Cathedral of Goslar in 1054 and Archbishop of Cologne two years later.[2] Due to his dominant position at the imperial court, Anno was able to influence other appointments. Anno's nephew, Burchard, was made Bishop of Halberstadt in 1059, and in 1063, his brother, Werner, became Archbishop of Magdeburg.[3]

According to contemporary sources, Anno led an ascetic life and was open to reform. Nevertheless, he was a fearsome adversary to anyone perceived as a threat to the interests of his archdiocese.[4] His plans to seize the prosperous monastery in Malmedy, challenging the authority of the Imperial abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy, caused much controversy and ultimately failed. On the other hand, he founded the Benedictine abbey of Michaelsberg, modelled on the Italian Abbey of Fruttuaria, which soon evolved to a centre of the Cluniac Reforms in Germany.

After the death of Emperor Henry III in 1056, the archbishop took a prominent part in the government of the empire during the minority of the six-year-old heir to the throne, Henry IV. He was the leader of the party which in April 1062 seized the person of Henry in the Coup of Kaiserswerth, and deprived his mother, Empress Agnes, of power.[5] Agnes, initially with the support of Pope Victor II, had stirred up several German princes against her rule by assigning extended fiefs to presumed supporters and by appointing her confidant Bishop Henry II of Augsburg regent. After he also had secured the Imperial regalia for himself, Anno for a short time was able to exercise the chief authority in the Empire, but he was soon obliged to share this with his fellow conspirators, Archbishop Adalbert of Bremen and Archbishop Siegfried of Mainz, retaining for himself the supervision of Henry's education and the title of magister.

The office of archchancellor of the Imperial Kingdom of Italy was at this period regarded as an appanage of the Archbishopric of Cologne, and this was probably the reason why Anno had a considerable share in settling a papal dispute brewing since 1061: relying on an assessment by his nephew Bishop Burchard of Halberstadt, he declared Alexander II to be the rightful pope at a synod held at Mantua in May 1064, and took other steps to secure his recognition against Empress Agnes' candidate Antipope Honorius II.[1] Returning to Germany, however, he found the chief power in the hands of Archbishop Adalbert of Bremen, and as he was disliked by the young emperor, Anno gradually lost ground at the imperial court though he regained some of his former influence when Adalbert fell from power in 1066. In the same year he was able to secure the succession of his nephew, Conrad of Pfullingen, as Archbishop of Trier. By 1072 he had become imperial administrator and thus the second most powerful man,[5] acting as an arbitrator in the rising Saxon Rebellion.

Shrine in Michaelsberg Abbey, Siegburg

In the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the City of Cologne attained great prosperity. Local crafts flourished; the spinners, weavers, and dyers, the woollen-drapers, goldsmiths, sword-cutlers, and armour-makers of Cologne were especially celebrated. No city north of the Alps was so rich in great churches, sanctuaries, relics, and religious communities. It was known as the "German Rome,". With the growth of the municipal prosperity, the pride of the citizens and their desire for independence also increased, and caused them to feel more dissatisfied with the sovereignty of the archbishop. This resulted in bitter feuds between the bishops and the city, which lasted for two centuries with varying fortunes. The first uprising occurred under Anno II, at Easter of the year 1074. The citizens rose against the archbishop, but were defeated within three days, and severely punished.[6] It was reported he had allied himself with William the Conqueror, King of England, against the emperor. Having cleared himself of this charge, Anno took no further part in public business and died in Siegburg Abbey on 4 December 1075,[7] where he was buried.

Veneration

Archbishop of Cologne showing monasteries he established (Vita Annonis Minor)

He was canonised in 1183 by Pope Lucius III.[3] He was a founder or co-founder of monasteries (Michaelsberg, Grafschaft, St. Maria ad Gradus, St. George, Saalfeld and Affligem) and a builder of churches, advocated clerical celibacy and introduced a strict discipline in a number of monasteries. He was a man of great energy and ability, whose action in recognizing Alexander II was of the utmost consequence for Henry IV and for Germany. He is the patron of gout sufferers.[5]

Anno was the subject of two important literary works, the Latin Vita Annonis, and the Middle High German Annolied.

See also

References

^ ab Campbell, Thomas. "St. Anno." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 30 Dec. 2012

^ Monks of Ramsgate. “Anno”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info. 20 July 2012 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

^ ab Oediger, Friedrich Wilhelm, "Anno II Of Steusslingen", New German Biography 1 (1953), pp 304-306

^ Rotondo-McCord, Jonathan. "Body snatching and Episcopal Power", Journal of Medieval History Vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 296-312. 1996

^ abc "Archbishop Anno II", Cologne Cathedral Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

^ Lins, Joseph. "Cologne." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 6 Dec. 2014

^ Butler, Alban. Lives of the Saints, Vol. XII, James Duffy, Dublin, 1866

Sources

Vita Annonis archiepiscopi Coloniensis, R. Koepke ed., MGH Scriptores 11 (Hannover 1854) 462-518.- Anno von Köln, Epistola ad monachos Malmundarienses, Neues Archiv der Gesellschaft für altere deutsche Geschichtskunde XIV (Hanover, 1876).

- Dunphy, Graeme (ed.) 2003. Opitz's Anno: The Middle High German Annolied in the 1639 Edition of Martin Opitz. Scottish Papers in Germanic Studies, Glasgow. [Diplomatic edition with English translation].

- Lindner, T., Anno II der Heilige, Erzbischof von Köln (1056-1075) (Leipzig 1869).

- Jenal, G., Erzbischof Anno II. von Köln (1056-75) und sein politisches Wirken. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Reichs- und Territorialpolitik im 11. Jahrhundert. Monographien zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 8, 2 vol. (Stuttgart 1974-1975).

- Schieffer, R., Die Romreise deutscher Bischöfe im Frühjahr 1070. Anno von Köln, Siegfried von Mainz und Hermann von Bamberg bei Alexander II., Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 35 (1971) 152-174.

Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Hermann II of Cologne | Archbishop of Cologne 1056–1075 | Succeeded by Hildholf |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anno II, Archbishop of Cologne. |