Portarlington, County Laois

Portarlington | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Portarlington train station | |

Portarlington Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 53°09′36″N 7°11′24″W / 53.160°N 7.190°W / 53.160; -7.190Coordinates: 53°09′36″N 7°11′24″W / 53.160°N 7.190°W / 53.160; -7.190 | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| County | County Laois & County Offaly |

| Elevation | 66 m (217 ft) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • Urban | 8,368 |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

Eircode routing key | R32 |

| Telephone area code | +353(0)57 |

| Irish Grid Reference | N540125 |

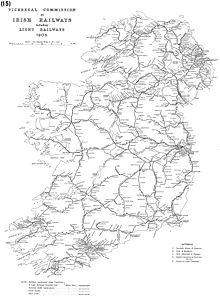

Island of Irish Rail 1906

Portarlington, historically called Cooletoodera[2] (from Irish: Cúil an tSúdaire, meaning "nook of the tanner"), is a town on the border of County Laois and County Offaly, Ireland. The River Barrow forms the border. The town was recorded in the 2016 census as having a population of 8,368.[1]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Huguenot settlement 1694

1.2 Lea Castle

1.3 Rotten borough

1.4 Geography

2 Demographics

3 Transport

3.1 Education

3.2 Commerce

4 Dirty Old Towns RTÉ TV Project

5 Sport

6 Culture

7 Festival Français de Portarlington

8 Notable people

9 International relations

9.1 Twin towns – Sister cities

10 See also

11 Notes and references

12 Further reading

13 External links

History

Blackhall Bridge

Portarlington was founded in 1666, by Sir Henry Bennet, who had been Home Secretary to Charles II and to whom that King, on his restoration, had made a grant of the extensive estates of Ó Díomasaigh, Viscount Clanmalier, confiscated after the Irish Rebellion of 1641. After some difficulties, the grant passed to Sir Henry Bennet of all the Ó Díomasaigh lands in the King's and Queen's Counties, and on 14 April 1664 he was created Baron Arlington of Harlington in the County of Middlesex. So great was the anxiety of these new settlers to efface all ancient recollections in Ireland, that the Parliament of Orrery and Ormond enacted that the governor and council should be able to give new English names instead of the Irish names of places; and that after a time such new names should be the only ones known or allowed in the country. In accordance with this enactment the borough created in Cooletoodera (Cúil an tSúdaire), received the name of Port-Arlington, or Arlington's Fort.[3]

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1821 | 2,877 | — |

| 1831 | 3,091 | +7.4% |

| 1841 | 3,106 | +0.5% |

| 1851 | 2,730 | −12.1% |

| 1861 | 2,581 | −5.5% |

| 1871 | 2,424 | −6.1% |

| 1881 | 2,357 | −2.8% |

| 1891 | 2,021 | −14.3% |

| 1901 | 1,943 | −3.9% |

| 1911 | 2,012 | +3.6% |

| 1926 | 1,954 | −2.9% |

| 1936 | 1,851 | −5.3% |

| 1946 | 2,092 | +13.0% |

| 1951 | 2,246 | +7.4% |

| 1956 | 2,720 | +21.1% |

| 1961 | 2,846 | +4.6% |

| 1966 | 2,804 | −1.5% |

| 1971 | 3,117 | +11.2% |

| 1981 | 3,386 | +8.6% |

| 1986 | 3,295 | −2.7% |

| 1991 | 3,211 | −2.5% |

| 1996 | 3,320 | +3.4% |

| 2002 | 4,001 | +20.5% |

| 2006 | 6,004 | +50.1% |

| 2011 | 7,788 | +29.7% |

| 2016 | 8,368 | +7.4% |

[4][5][6][7][8] | ||

Huguenot settlement 1694

Following the failure of Henry Bennet's English colony, Port Arlington was re-established with the settlement of Huguenot refugees following the Treaty of Limerick:

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

Unique among the French Protestant colonies established or augmented in Ireland following the Treaty of Limerick (1691), the Portarlington settlement was planted on the ashes of an abortive English colony.[9]

Fifteen or more Huguenot families who were driven from France as religious refugees settled on the ashes of Bennet's colony, and the settlement was unique among the Huguenot settlements in Ireland in that the French language survived, being used in church services till the 1820s and continuing to be taught in the town school.

... and till within the last twenty years divine service was performed in the French language. In the RC divisions Portarlington is the head of a union or district, called Portarlington, Emo and Killinard ...[10]

The Protestant Bishop of Kildare came to Portarlington to consecrate the new French Church, 1694.[11] To the present day one of the town's main thoroughfares is still named 'French Church Street', with the original French church (1694) situated just off the market square.[12][13]

The relationship to the French influence with Portarlington is celebrated every July with The French Festival.

Lea Castle

On the outskirts of the parish lies Lea Castle. The remnants of a great Norman castle built in 1260 by William de Vesey. It changed hands many times during its violent history, for example, it was burned by Fionn Ó Díomasaigh's men in 1284, rebuilt by de Vesey and given to the king, burned along with its town by the Scots army in 1315, burned by the O'Moores in 1346, captured by the O'Dempseys in 1422 and then lost to the Earl of Ormond in 1452, used by Silken Thomas Fitzgerald as a refuge in 1535, mortgaged to Sir Maurice Fitzgerald in 1556, and leased to Robert Bath in 1618. It was used by the confederates as a mint in the 1640s rebellion until Cromwellians blew up the fortifications by stuffing the stairways with explosives. The castle was never used as a fortification again.

Trescon Mass Rock: Just outside the town in an area known as Trescon, a mass rock (Carraig an Aifrinn in Irish) can be found deep in a wooded area.

Trescon mass rock is a stone used in mid-seventeenth century Ireland as a location for Catholic worship. Isolated locations were sought to hold religious ceremony, as Catholic mass was a matter of difficulty and danger at the time as a result of both Cromwell's campaign against the Irish, and the Penal Laws of 1695, whereby discrimination and violence against Catholics was legal. Bishops were banished and priests had to register thereafter. In some cases priest hunters were used.

The rebellion of 1798 resulted in several local men from Lea castle, being apprehended and subsequently put to death by hanging in the town's market square. A memorial in the shape of a Celtic cross with the rebels details was commissioned and erected in 1976. The memorial stands close to the perimeter wall of the French church in the market square .

Rotten borough

Two borough minute books have survived and in the National Library of Ireland Ms 90 for 1727–1777, and Ms 5095 for 1777–1841; they reveal the limitation of freemen, and increasing control by the Dawson-Damer family, the Earls of Portarlington. (See also John S. Powell, The Portarlington maces and its borough history 1669–1841, 2011). Imperial political democratic practices were responsible for turning Portarlington into a perfectly rotten borough. The reason was to preserve the planters positions politically and economically. Below is an extract that shows that a corporation of 15 people was solely responsible for the persistent re-election of perfect strangers to parliament to represent the other 2800 people.

"Prior to the legislative Union between Great Britain and Ireland, this borough sent two Members to the Irish Parliament; since 1800 it has returned one to the Imperial Parliament, and so close has been this corporation, that for 50 years previous to the last general election, the nominee of the Dawson family, commonly a total stranger to the borough, was always returned without a contest. According to the Parliamentary Returns of May 1829 and June 1830, the number of electors, resident and non-resident, was 15; that is, all the members of the corporation." Inquiry held 21, 23, and 24 September 1833, before John Colhoun and Henry Baldwin.

Geography

The Spire

Portarlington is split by the River Barrow. With County Offaly on the north bank and County Laois on the south Bank. The town is mostly flat, with some slight street undulations. The town was partially built on the river's flood plain. Better drainage recently has resulted in fewer floodings to areas close to the town.

Crossing the river into Co Offaly, the land becomes marshy and wet with extensive peat bogs.These peat bogs are broken by some glacial hills, one such hill is called 'Derryvilla' Hill.These hills have been used for gravel and sand production.

The southern end of the town is dominated visually by another glacial hill, know locally as 'Corrig'.

This hill is topped by a stone structure called the 'spire'. The spire was built the latter half of the 19th century. Next to the spire is the town's water supply reservoir. The reservoir uses the gravity afforded by the hill to supply water to the town below.

The land on the south side of town is well drained and rises slowly towards the hill of Corrig. This land is agriculturally productive and market farming is practiced here.[citation needed]

Demographics

1841–1881, the population of Laois, which was then called the Queen's County, halved from mass emigration and starvation, in spite of the fact that the county (and most other counties) increased food production throughout the period.[citation needed]

The county suffered badly during the Great Famine (1845–47); the county's population dropped from over 153,000 in 1841 to just over 73,000 in 1881.[citation needed]

Although figures for Portarlington are not readily available, it would be inconceivable to think that the town's population would have fared any better that those of the rest of the county.

Famine graveyards are known locally.

The population of Portarlington (and its environs) has risen by 50.1% from 2002 to 2006:[14]

- 1821 ...2877

- 1831 ...3091

- 1991 ...3221

- 2002 ... 4001

- 2006 ... 6,004 (Portarlington South, Laois - 4,395) & (Portarlington North, Offaly - 1,609)

- 2011 ... 7,788 (Portarlington South, Laois - 5,847) & (Portarlington North, Offaly - 1,941)[15]

Transport

Portarlington is a focal point of the Irish railway network, being situated on the junction for services to the west (Galway, Mayo), the south (Cork, Limerick, Tralee) and the east (Dublin, Kildare). Portarlington halt opened on 26 June 1847.[16]

Due to the rail service there is a very limited public transport by road. As of January 2017 only one intercity bus service operates direct to Dublin. Now operated by JJ Kavanagh and Sons, (replacing "Silver Dawn" who had run it for approximately 20 years)[citation needed] this service serves UCD once a day up and return.[citation needed] There is a local-link town service operated by Slieve Bloom Coaches linking Portarlington with Portlaoise and also with Tullamore.[17]

An additional private operator, Dublin Coach (known locally as 'the green bus' due its livery) operates an hourly service to Kildare Village Outlet via Monasterevin. From Monasterevin there is an hourly, 24 hour, service to Dublin Airport via Kildare Town, Newbridge, Naas and Red Cow Luas Station. Services from Kildare Village Outlet are available half-hourly direct to the Red Cow Luas Station and Dublin city centre. A weekday service by JJ Kavanagh and Sons via Portarlington en route to NUI Maynooth University and Institute of Technology, Carlow. This service operates during college term only.[citation needed]

Education

Coláiste Íosagáin is the main secondary school in Portarlington.[18] The school, which is located on the Offaly side of the border, has numerous ongoing programmes including Transition Year, Leaving Cert Applied and Leaving Cert Vocational Programme.

There are three Primary Schools,all located on the Laois side of the border.

There is also a third level education college providing various courses suitable for post-secondary pupils as well as adult education courses en route to university.

Commerce

The local economy and commerce has been dominated by the agricultural sector for many generations.[citation needed]

In recent years[when?] the town's location in relation to Dublin coupled with its railways services, assisted the town to grow, by attracting people to relocate. This growth in population was a welcomed change from the near population stagnation suffered throughout Ireland for generations.[tone] However, recent developments locally and nationally has resulted in the unemployment levels rapidly rising. The Leinster Express in August 2010, reported 3,406 people claiming social welfare in Portarlington. As of January 2017 that figure has reduced somewhat.[citation needed]

Major employers are a shadow of their former selves.[tone] Electricity generation at the local power station ended in the early 1990s. The cooling tower and turbine hall have since been demolished. Industrialised peat production within the semi-state company Bord na Móna has been decimated. The production of jewellery and cosmetics ended with the demise of 'Avon' Arlington on the Canal Road. The imposing redbrick Avon factory has since been demolished. Local Siac Butlers Steel located on the Lea Road is also undergoing serious decline, brought about by the demise of the construction industry. Flour production still takes place in Odlum's mill. The East End Hotel over the recent years has tried, unsuccessfully, to reopen under new management. As of 23rd June 2017 it reopened under new local management.

The town has seen a spate of new start-up businesses in recent years[when?] leading to an improvement in employment. These businesses range from ecommerce (IT industry) to musical instrument manufacturing. Portarlington is also a hub for Fastway Couriers servicing a large number of surrounding counties.[citation needed]

Dirty Old Towns RTÉ TV Project

In 2012 RTÉ chose Portarlington as the focal point for the TV show Dirty Old Towns. The town was filmed extensively over a number of weeks as the local people, under the eye of presenter Dermot Gavin, changed what was becoming an eyesore into what has become a much more colourful and vibrant town. The show ran for 6 weeks with a lot of focus in each episode on the work carried out by local people and businesses. The show's producers remarked on the fantastic response to the call and the tremendous effort put in by all to see the town transformed. The most striking addition to the town was along the banks of the River Barrow where enormous red-painted letters spelling "L I F E" were erected. The original spelling was "L I V E" however when travelling from the Offaly side of the town it looked like the word "E V I L". Other additions to the town have been two all weather soccer pitches which have been Football Association of Ireland sanctioned for soccer schools. An old run down building along the main street revealed enormous potential and is under development as a boxing club, a conference hall and perhaps even a temporary cinema. The People's Park has been re-developed with new attractions for the many children of the town. Old shops have been redecorated and closed premises have all been repainted. The old French School on the banks of the river had been neglected for many years and with help from Dulux paints and the local Lions Club it had a major facelift. The exposure from the TV show had a dramatic effect on the town, making it much more colourful and welcoming.

Sport

| Club | Sport | League | Venue | Established |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portarlington Mud Dogs | American Football | Irish American Football League | The Dog Pound | 2007 |

| Gracefield GAA | Gaelic Athletic Association | Senior Football Championship | Gracefield | 1920 |

Portarlington | Gaelic Athletic Association | Senior Football Championship | McCann Park | 1893 |

O'Dempsey's GAA | Gaelic Athletic Association | Senior Football Championship | The Old Pound | 1951 |

| Gracefield FC | Soccer | [CCFL] | Botley Lane | 2009 |

Portarlington RFC | Rugby Union | Leinster League | Lea Road | 1974 |

| Portarlington Kestrels Basketball Club | Basketball | Superleague | Coláiste Íosagáin | 1996 |

| Arlington F.C. | Soccer | CCFL | Castle Park | 1967 |

| Portarlington Town F.C. | Soccer | CCFL | Coláiste Íosagáin | 2012 |

| Portarlington Lawn Tennis Club | Tennis | Laois League Division 2 | Station Road | 1954 |

| Heritage Golf Club | Golf | N/A | Killenard | |

| Portarlington Golf Club | Golf | N/A | Garryhinch | 1908 |

| Portarlington Taekwondo School | Taekwondo | N/A | Portarlington Business Park | 2010 |

| SBG Portarlington | Mixed Martial Arts | N/A | Riverside Business Park | 2017 |

| Portarlington Angling Club | Fishing | N/A |

Culture

The People's Museum, situated within the Catholic Club on Main Street in Portarlington is small but holds many different exhibits ranging from local memorabilia to a Bronze Age Celtic dagger.

The town appeared in the 1993 Irish film 'Into the West', a touching story about a family from Ireland's Travelling community. Portarlington, its Savoy cinema (now closed) and the nearby Lea Castle appear in the film. The town is also mentioned in Christy Moore's song 'Welcome to the Cabaret', featured on his 1994 album 'Christy live at the Point'.

Outdoor pursuits of angling and hunting are available.

Cuisine in the town is varied with pub grub, Chinese, Indian and several fast food restaurants.

Extensive architectural history ranging from the Middle Ages to Huguenot and Georgian houses can be seen.

Festival Français de Portarlington

A French Festival (Festival Français de Portarlington) takes place annually around 15–17 July. Having been dormant for seven years it was revived in 2010. The festival is now weekend-long with a wide range of entertainment to suit all interests, including live music (both open air concerts and in-pub gigs), dance, sport, history, food and a parade led by the Festival Queen which includes local businesses, clubs, groups and schools. The French influence in Portarlington is celebrated with French Street entertainers as well as French musicians playing live on the opening day. There is also the lively and well aniticapted National Snail Eating Championships or "Championnats d'escargots National Eating" held on the final day of the festival.

Festival goers can obtain many delights at the Town Market such as cheeses, pastries, soaps and accessories. The entertainment provided over the weekend includes a carnival, arts & crafts, face painters, bouncing castles and much more. Since its revival the festival has grown steadily with more events and a healthier promotional budget drawing in larger crowds. So much so that the festivities now take in three full days and continue well into the night with outdoor live music from various artists drawing large audiences.

Notable people

Peter Burrowes (1753–1841) – Irish barrister and politician.

Richard Pennefather (1773–1859) leading Irish judge, went to school in Portarlington.

Edward Carson, Baron Carson (1854–1935), Irish barrister, politician and judge, went to school in Portarlington.

John Wilson Croker (1780–1857) politician and essayist, creator of the term Conservative for the British political party, went to school in Portarlington

Feargus O'Connor (1794–1855) Chartist leader, went to Thomas Willis's school in Portarlington and attempted to elope with the headmaster's daughter.

Jonathan Swift (1667–1745) Prolific writer and satirist, wrote large part of his famous work Gulliver's Travels in Woodbrook House in Portarlington.[19][20]

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Portarlington, as designated by Sister Cities International is sister city to:

Arlington, Massachusetts

Arlington, Massachusetts

See also

- List of towns and villages in Ireland

- Market Houses in Ireland

Notes and references

^ ab "Sapmap Area - Settlements - Portarlington". Census 2016. Central Statistics Office Ireland. 2016. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Placenames Database of Ireland

^ Rev. M Comerford Collections relating to the Dioceses of Kildare and Leighlin Vol 2 (1883).

^ Census for post 1821 figures.

^ http://www.histpop.org

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 2013-08-24.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Lee, JJ (1981). "Pre-famine". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

^ Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x.

[dead link]

^ Hylton, Raymond Pierre (1987), "The Huguenot settlement at Portarlington, 1692–1771", in Caldicott, C.E.J.; Gough, Hugh; Pittion, Jean-Paul, The Huguenots and Ireland : anatomy of an emigration : [proceedings of the Dublin Colloquium on the Huguenot Refuge in Ireland 1685–1985, 9th–12th April, 1985, Trinity College Dublin, University College Dublin], Dun Laoghaire: Glendale Press, pp. 297–315

^ A Topographical dictionary of Ireland Page 465 Samuel Lewis – 1837

^ Raymond Hylton Ireland's Huguenots and their refuge, 1662–1745: an unlikely haven Page 194 2005 "The Bishop of Kildare did come to Portarlington to consecrate the churches, backed by two prominent Huguenot Deans of ... Moreton held every advantage and for most of the Portarlington Huguenots there could be no option but acceptance ...

^ Grace Lawless Lee The Huguenot Settlements in Ireland 2009 Page 169

^ Raymond P. "The Huguenot Settlement at Portarlington, ...

^ "Demographic context" (PDF). Offaly County Council Development Plan 2009 – 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

^ http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/documents/census2011vol1andprofile1/Table_5.pdf

^ "Portarlington station" (PDF). Railscot – Irish Railways. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

^ http://www.slievebloomcoaches.ie/portarlington_16.html

^ "Coláiste Íosagáin - Secondary School in Portarlington, Co. Laois, Ireland". www.colaisteiosagainport.ie. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

^ http://www.independent.ie/lifestyle/property-homes/the-house-that-begat-gullivers-travels-is-not-for-the-little-people-26446253.html

^ http://www.mygullivertravels.com/author-other-works.html

Further reading

Dempsey, Karen, "Lea Castle, Co. Laois: the story so far", The Castle Studies Group Journal, 30: 237–252- Goode, P.J.: O'Dempsey Chronicles

- Huguenot Society of London: Registers of the French Church of Portarlington, Ireland. Publications, vol. 19. 1908, reprinted 1969.

- Mathews, Ronnie: Portarlington, the inside story,

ISBN 0863350275, 1999. - Mathews, Ronnie: Portarlington, the old town, a collection of facts, images and stories from the past. 2012.

- Powell, John Stocks: Huguenots planters Portarlington,

ISBN 0951629921, 1994 - Powell, John Stocks: Portarlington 1800–1850 the combined registers of Portarlington, Lea ...

ISBN 9780953801091, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portarlington, County Laois. |

- Portarlington Community Website

- Portarlington Community Facebook page