Government spending

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

| Public finance |

|---|

|

Policies

|

Fiscal policy

|

Monetary policy

|

Trade policy

|

|

Optimum

|

Reform

|

Government spending or expenditure includes all government consumption, investment, and transfer payments.[1][2] In national income accounting the acquisition by governments of goods and services for current use, to directly satisfy the individual or collective needs of the community, is classed as government final consumption expenditure. Government acquisition of goods and services intended to create future benefits, such as infrastructure investment or research spending, is classed as government investment (government gross capital formation). These two types of government spending, on final consumption and on gross capital formation, together constitute one of the major components of gross domestic product.

Government spending can be financed by government borrowing, or taxes. Changes in government spending is a major component of fiscal policy used to stabilize the macroeconomic business cycle.

Contents

1 Macroeconomic fiscal policy

2 Current use: final consumption expenditure

3 National defense spending

4 Healthcare and medical research

5 Infrastructure and investment: gross fixed capital formation

6 Transfer payment spending

7 Per capita spending

8 As a percentage of GDP

9 Public social spending by country

10 See also

11 References

12 External links

Macroeconomic fiscal policy

The Market for Capital (the Loanable Funds Market) and the Crowding Out Effect. An increase in government deficit spending "crowds out" private investment by increasing interest rates and lowering the quantity of capital available to the private sector.

Government spending can be a useful economic policy tool for governments. Fiscal policy can be defined as the use of government spending and/or taxation as a mechanism to influence an economy.[3][4] There are two types of fiscal policy: expansionary fiscal policy, and contractionary fiscal policy. Expansionary fiscal policy is an increase in government spending or a decrease in taxation, while contractionary fiscal policy is a decrease in government spending or an increase in taxes. Expansionary fiscal policy can be used by governments to stimulate the economy during a recession. For example, an increase in government spending directly increases demand for goods and services, which can help increase output and employment. On the other hand, contractionary fiscal policy can be used by governments to cool down the economy during an economic boom. A decrease in government spending can help keep inflation in check.[3] During economic downturns, in the short run, government spending can be changed either via automatic stabilization or discretionary stabilization. Automatic stabilization is when existing policies automatically change government spending or taxes in response to economic changes, without the additional passage of laws.[5][3] A primary example of an automatic stabilizer is unemployment insurance, which provides financial assistance to unemployed workers. Discretionary stabilization is when a government takes actions to change government spending or taxes in direct response to changes in the economy. For instance, a government may decide to increase government spending as a result of a recession.[5] With discretionary stabilization, the government must pass a new law to make changes in government spending.[3]

John Maynard Keynes was one of the first economists to advocate for government deficit spending as part of the fiscal policy response to an economic contraction. According to Keynesian economics, increased government spending raises aggregate demand and increases consumption, which leads to increased production and faster recovery from recessions. Classical economists, on the other hand, believe that increased government spending exacerbates an economic contraction by shifting resources from the private sector, which they consider productive, to the public sector, which they consider unproductive.[6]

In economics, the potential "shifting" in resources from the private sector to the public sector as a result of an increase in government deficit spending is called crowding out.[3] The figure to the right depicts the market for capital, otherwise known as the market for loanable funds. The downward sloping demand curve D1 represents demand for private capital by firms and investors, and the upward sloping supply curve S1 represents savings by private individuals. The initial equilibrium in this market is represented by point A, where the equilibrium quantity of capital is K1 and the equilibrium interest rate is R1. If the government increases deficit spending, it will borrow money from the private capital market and reduce the supply of savings to S2. The new equilibrium is at point B, where the interest rate has increased to R2 and the quantity of capital available to the private sector has decreased to K1. The government has essentially made borrowing more expensive and has taken away savings from the market, which "crowds out" some private investment. The crowding out of private investment could limit the economic growth from the initial increase government spending.[5][4]

Current use: final consumption expenditure

Government acquisition of goods and services for current use to directly satisfy individual or collective needs of the members of the community is called government final consumption expenditure (GFCE.) It is a purchase from the national accounts "use of income account" for goods and services directly satisfying of individual needs (individual consumption) or collective needs of members of the community (collective consumption). GFCE consists of the value of the goods and services produced by the government itself other than own-account capital formation and sales and of purchases by the government of goods and services produced by market producers that are supplied to households—without any transformation—as "social transfers" in kind.[7]

National defense spending

The United States spends vastly more than other countries on national defense. The table below shows the top 10 countries with largest military expenditures as of 2015, the most recent year with publicly available data. As the table suggests, the United States spent nearly 3 times as much on the military than China, the country with the next largest military spending. The U.S. military budget dwarfed spending by all other countries in the top 10, with 8 out of countries spending less than $100 billion in 2016.

List by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute 2017 Fact Sheet (for 2016)[8] SIPRI Military Expenditure Database[9]

|

Healthcare and medical research

Research Australia[12] found 91% of Australians think ‘improving hospitals and the health system’ should be the Australian Government’s first spending priority.

Crowding 'in' also[13] happens in university life science research Subsidies, funding and government business or projects like this are often justified on the basis of their positive return on investment. Life science crowding in contrasts with crowding out in public funding of research more widely:[14] “10% increase in government R&D funding reduced private R&D expenditure by 3%...In Australia the average cost of public funds is estimated to be $1.20 and $1.30 for each dollar raised (Robson, 2005). The marginal cost is probably higher, but estimates differ widely depending on the tax that is increased.”

Infrastructure and investment: gross fixed capital formation

Government acquisition intended to create future benefits, such as infrastructure investment or research spending, is called gross fixed capital formation, or government investment, which usually is the largest part of the government.[15] Acquisition of goods and services is made through production by the government (using the government's labour force, fixed assets and purchased goods and services for intermediate consumption) or through purchases of goods and services from market producers. In economic theory or in macroeconomics, investment is the amount purchased per unit of time of goods which are not consumed but are to be used for future production (i.e. capital). Examples include railroad or factory construction.

Infrastructure spending is considered government investment because it will usually save money in the long run, and thereby reduce the net present value of government liabilities.

Spending on physical infrastructure in the U.S. returns an average of about $1.92 for each $1.00 spent on nonresidential construction because it is almost always less expensive to maintain than repair or replace once it has become unusable.[16]

Likewise, government spending on social infrastructure, such as preventative health care, can save several hundreds of billions of dollars per year in the U.S., because for example cancer patients are more likely to be diagnosed at Stage I where curative treatment is typically a few outpatient visits, instead of at Stage III or later in an emergency room where treatment can involve years of hospitalization and is often terminal.[17]

Transfer payment spending

Government expenditures that are not acquisition of goods and services, and which represent transfers of money such as social security payments, are called transfer payments. These payments are considered to be non-exhaustive[jargon] because they do not directly absorb resources or create output. In other words, transfers are made without an exchange of goods or services.[18] Examples of certain transfer payments include welfare (financial aid), social security, and government giving subsidies to certain businesses (firms).

Per capita spending

In 2010 national governments spent an average of $2,376 per person, while the average for the world's 20 largest economies (in terms of GDP) was $16,110 per person. Norway and Sweden expended the most at $40,908 and $26,760 per capita respectively. The federal government of the United States spent $11,041 per person. Other large economy country spending figures include South Korea ($4,557), Brazil ($2,813), Russia ($2,458), China ($1,010), and India ($226).[19] The figures below of 42% of GDP spending and a GDP per capita of $54,629 for the U.S. indicate a total per person spending including national, state, and local governments was $22,726 in the U.S.

As a percentage of GDP

Tax Burden as a Percentage of GDP (2014 Index of Economic Freedom).[20]

Public spending / GDP in Europe.

Legend: maroon > 55%, red 50–55%, orange 45–50%, yellow 40–45%, green 35–40%, blue 30–35%

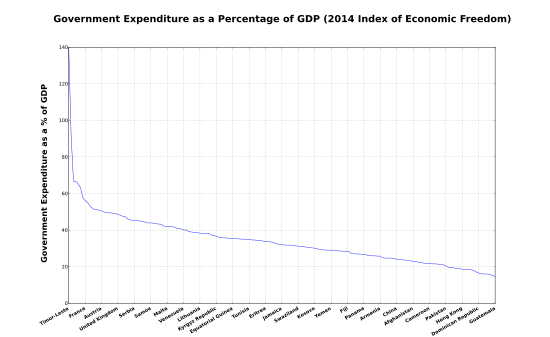

This is a list of countries by government spending as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) for the listed countries, according to the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom[20] by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal. Tax revenue is included for comparison.

| Country | Tax burden % GDP | Govt. expend. % GDP |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | 23 | |

| 23 | 28 | |

| 10 | 40 | |

| 6 | 39 | |

| 35 | 41 | |

| 17 | 25 | |

| 26 | 35 | |

| 42 | 51 | |

| 13 | 34 | |

| 16 | 23 | |

| 3 | 31 | |

| 10 | 16 | |

| 27 | 41 | |

| 25 | 36 | |

| 44 | 53 | |

| 23 | 29 | |

| 16 | 22 | |

| 14 | 38 | |

| 22 | 35 | |

| 39 | 49 | |

| 28 | 32 | |

| 35 | 39 | |

| 26 | 34 | |

| 14 | 24 | |

| 4 | 19 | |

| 14 | 40 | |

| 11 | 20 | |

| 11 | 22 | |

| 31 | 42 | |

| 20 | 32 | |

| 9 | 16 | |

| 5 | 26 | |

| 19 | 23 | |

| 19 | 24 | |

| 15 | 29 | |

| 12 | 22 | |

| 24 | 29 | |

| 8 | 26 | |

| 22 | 18 | |

| 13 | 26 | |

| 33 | 43 | |

| 24 | 67 | |

| 27 | 46 | |

| 35 | 43 | |

| 48 | 58 | |

| 20 | 35 | |

| 24 | 36 | |

| 13 | 16 | |

| 18 | 44 | |

| 14 | 32 | |

| 15 | 22 | |

| 2 | 35 | |

| 50 | 34 | |

| 33 | 38 | |

| 11 | 18 | |

| 23 | 28 | |

| 43 | 55 | |

| 44 | 56 | |

| 10 | 25 | |

| 13 | 26 | |

| 25 | 32 | |

| 37 | 45 | |

| 15 | 24 | |

| 31 | 52 | |

| 11 | 15 | |

| 16 | 22 | |

| 9 | 21 | |

| 21 | 31 | |

| 13 | 34 | |

| 16 | 26 | |

| 14 | 19 | |

| 36 | 49 | |

| 36 | 47 | |

| 7 | 27 | |

| 12 | 19 | |

| 9 | 22 | |

| 2 | 45 | |

| 28 | 48 | |

| 33 | 45 | |

| 43 | 50 | |

| 23 | 32 | |

| 28 | 42 | |

| 14 | 33 | |

| 15 | 22 | |

| 20 | 29 | |

| 20 | 92 | |

| N/A | N/A | |

| 26 | 30 | |

| 1 | 39 | |

| 19 | 36 | |

| 14 | 21 | |

| 27 | 39 | |

| 17 | 30 | |

| 38 | 63 | |

| 20 | 31 | |

| 1 | 67 | |

| N/A | N/A | |

| 16 | 38 | |

| 37 | 42 | |

| 35 | 17 | |

| 11 | 16 | |

| 20 | 35 | |

| 15 | 29 | |

| 16 | 43 | |

| 14 | 25 | |

| 34 | 42 | |

| 18 | 28 | |

| 18 | 25 | |

| 11 | 27 | |

| 12 | 65 | |

| 31 | 39 | |

| 33 | 45 | |

| 24 | 44 | |

| 23 | 35 | |

| 20 | 34 | |

| 28 | 37 | |

| 13 | 19 | |

| 39 | 50 | |

| 32 | 48 | |

| 18 | 26 | |

| 14 | 20 | |

| 5 | 29 | |

| 26 | 31 | |

| 43 | 44 | |

| 2 | 38 | |

| 9 | 20 | |

| 18 | 27 | |

| 26 | 29 | |

| 13 | 19 | |

| 17 | 19 | |

| 12 | 16 | |

| 32 | 44 | |

| 31 | 49 | |

| 3 | 31 | |

| 28 | 37 | |

| 30 | 36 | |

| 13 | 27 | |

| 25 | 35 | |

| 22 | 30 | |

| 23 | 44 | |

| 17 | 49 | |

| 4 | 35 | |

| 19 | 29 | |

| 35 | 45 | |

| 32 | 36 | |

| 12 | 22 | |

| 14 | 17 | |

| 29 | 38 | |

| 37 | 51 | |

| 37 | 51 | |

| 27 | 32 | |

| 32 | 45 | |

| 12 | 21 | |

| 7 | 18 | |

| 19 | 27 | |

| 23 | 31 | |

| 45 | 51 | |

| 29 | 34 | |

| 10 | N/A | |

| 9 | 23 | |

| 20 | 27 | |

| 15 | 27 | |

| 16 | 23 | |

| 61.5 | 51.2 | |

| 17 | 24 | |

| 18 | 29 | |

| 17 | 35 | |

| 21 | 35 | |

| 25 | 35 | |

| 18 | 15 | |

| 17 | 21 | |

| 38 | 46 | |

| 6 | 24 | |

| 36 | 49 | |

| 25.1 | 41.6 | |

| 27 | 33 | |

| 20 | 31 | |

| 16 | 25 | |

| 13 | 40 | |

| 21 | 31 | |

| 5 | 29 | |

| 19 | 24 | |

| 30 | 35 | |

| N/A | N/A | |

| 24 | 34 |

Public social spending by country

Government Expenditure as a Percentage of GDP (2014 Index of Economic Freedom).[20]

Public social spending comprises cash benefits, direct in-kind provision of goods and services, and tax breaks with social purposes provided by general government (that is central, state, and local governments, including social security funds).[21]

| Country | Public social spending % of GDP |

|---|---|

| 31.7 | |

| 30.6 | |

| 29.2 | |

| 28.9 | |

| 28.8 | |

| 28.0 | |

| 26.7 | |

| 26.4 | |

| 25.4 | |

| 25.0 | |

| 24.1 | |

| 23.9 | |

| 22.4 | |

| 22.3 | |

| 22.2 | |

| 21.5 | |

| OECD | 21.0 |

| 20.7 | |

| 19.7 | |

| 19.6 | |

| 19.5 | |

| 19.4 | |

| 19.4 | |

| 19.0 | |

| 18.8 | |

| 17.2 | |

| 17.0 | |

| 17.0 | |

| 16.0 | |

| 15.7 | |

| 14.4 | |

| 11.2 | |

| 10.1 |

See also

- Rahn curve

- Government operations

- Public expenditure

- Public finance

- Government budget

- Government waste

- Fiscal policy

- Tax

- Mandatory spending

- Taxpayers unions

- Eurostat

- Government spending in the United Kingdom

- Government spending in the United States

References

^ "Frequently Asked Questions: BEA seems to have several different measures of government spending. What are they for and what do they measure?". Bureau of Economic Analysis. 28 May 2010. Retrieved 12 July 2014..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Robert Barro and Vittorio Grilli (1994), European Macroeconomics, Ch. 15–16. Macmillan,

ISBN 0-333-57764-7.

^ abcde Taylor, Timothy, (2017). Principles of Macroeconomics: Economics and the Economy (Fourth ed.). Minneapolis: Textbook Media Press. pp. 366–340. ISBN 9780996996334. OCLC 1001342630.

^ ab Gregory, Mankiw (2014). Principles of Economics (Seventh ed.). Stamford, CT: Southwestern Publishing Group. ISBN 9781285165875. OCLC 884664951.

^ abc Jonathan, Gruber. Public Finance and Public Policy (Fifth ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 9781464143335. OCLC 914290290.

^ Irvin, Tucker (2012). Macroeconomics for Today (8th ed.). Mason, OH: Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781133435051. OCLC 830731890.

^ F. Lequiller, D. Blades: Understanding National Accounts, Paris: OECD 2006, pp. 127–30

^ "Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2016" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

^ "Data for all countries from 1988–2016 in constant (2015) USD (pdf)" (PDF). SIPRI. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

^ ab SIPRI estimate.

^ The figures for Saudi Arabia include expenditure for public order and safety and might be slightly overestimated.

^ "Research Australia". crm.researchaustralia.org.

^ http://www.nber.org/papers/w15146.pdf

^ "Do innovation programs actually increase innovation?". robwiblin.com. 24 September 2012.

^ "Gross capital formation" Statistics Explained European Union Statistics Directorate, European Commission

^ Cohen, Isabelle; Freiling, Thomas; Robinson, Eric (January 2012). The Economic Impact and Financing of Infrastructure Spending (PDF) (report). Williamsburg, Virginia: Thomas Jefferson Program in Public Policy, College of William & Mary. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

^ Hogg, W.; Baskerville, N.; Lemelin, J. (2005). "Cost savings associated with improving appropriate and reducing inappropriate preventive care: Cost-consequences analysis" (PDF). BMC Health Services Research. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-5-20. PMC 1079830. PMID 15755330.

^ Bishop, Matthew (2012). "Economics AZ– terms beginning with T;transfer". The Economist. Retrieved 11 July 2012.Payments that are made without any good or service being received in return. Much PUBLIC SPENDING goes on transfers, such as pensions and WELFARE benefits. Private-sector transfers include charitable donations and prizes to lottery winners.

^ CIA World Factbook, population data from 2010, Spending and GDP data from 2011. Note: these numbers do not include U.S. state and local government spending which when included bring the per capita spending to $16,755

^ abc "Economic Data and Statistics on World Economy and Economic Freedom". www.heritage.org.

^ ab "Social spending Public, % of GDP, 2015". OECD.

OECD data

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Government Spending. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Public expenditure. |

- OECD Government spending statistics

- Canadian Governments Compared

- Eurostat's government spending per sector