National Action Party (Mexico)

National Action Party Partido Acción Nacional | |

|---|---|

| |

| President | Marko Cortés Mendoza |

| Secretary-General | Héctor Larios Córdova |

| Founder | Manuel Gómez Morín |

| Founded | 16 September 1939 (1939-09-16) |

| Headquarters | Av. Coyoacán No. 1546 Col. Del Valle, Delegación Benito Juárez, D.F., Mexico City |

| Youth wing | Acción Juvenil (Youth Action) |

| Ideology | Conservatism Liberal conservatism[1][2][3] Christian democracy[4] |

| Political position | Centre-right[5][6][7] to right-wing[8][9][10] |

| International affiliation | International Democrat Union Centrist Democrat International |

| Regional affiliation | Union of Latin American Parties Christian Democrat Organization of America |

| Colors | Blue and White |

| Slogan | Por una patria ordenada y generosa y una vida mejor y más digna para todos (For an orderly and generous homeland and a better and more dignified life for all) |

| Seats in the Chamber of Deputies | 79 / 500 |

| Seats in the Senate | 24 / 128 |

| Governorships | 11 / 32 |

| Seats in State legislatures | 229 / 1,123 |

| Website | |

| http://www.pan.org.mx/ | |

| |

The National Action Party (Spanish: Partido Acción Nacional, PAN), founded in 1939, is a conservative political party in Mexico, one of the three main political parties in Mexico. Since the 1980s, it has been an important political party winning local, state, and national elections. In 2000, PAN candidate Vicente Fox was elected president for a six-year term; in 2006, PAN candidate Felipe Calderón succeeded Fox in the presidency. During the period 2000-2012, both houses of the Congress of the Union (the federal legislature) contained PAN pluralities, but the party had a majority in neither. In the 2006 legislative elections the party won 207 out of 500 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 52 out of 128 Senators. In the 2012 legislative elections, the PAN won 38 seats in the Senate, and 114 seats in the Chamber of Deputies.[11] The members of this party are colloquially called Panistas.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Founding in the 20th century

1.2 21st century

1.2.1 Defeating the PRI to presidency

1.2.2 Return of the PRI to presidency

2 Ideology

2.1 Economic policies

2.2 Social policies

2.2.1 Abortion

2.2.2 Opposition to same-sex unions in Mexico

3 Party Presidents

4 Electoral history

4.1 Presidential elections

4.2 Congressional elections

4.2.1 Chamber of Deputies

4.2.2 Senate elections

5 Bibliography

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

History

Founding in the 20th century

Manuel Gómez Morín, founder of the PAN in 1939

| Part of a series on |

| Christian democracy |

|---|

|

Organizations

|

Ideas

|

Documents

|

People

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

Variants

|

Concepts

|

People

|

Organizations

|

Religious conservatism

|

National variants

|

Related topics

|

|

The National Action Party was founded in 1939 by Manuel Gómez Morín, who had held a number of important government posts in the 1920s and 1930s. He saw the need for the creation of a permanent political party rather than an ephemeral organization to oppose the expansion of power by the post-revolutionary Mexican state.[12][13] When Gómez Morín was rector of UNAM between 1933 and 1935, the government attempted to impose socialist education. In defending academic freedom, Gómez Morín forged connections with individuals and groups that later came together in the foundation of the PAN in September 1939. The Jesuit student organization, Unión Nacional de Estudiantes Católicos (UNEC), provided a well-organized network of adherents who successfully fought the imposition of a particular ideological view by the state. Gómez Morín was not himself a militant Catholic, but he was a devout believer who rejected liberalism and individualism.[14] In 1939, Gómez Morín and a significant number of UNEC's leadership came together to found the PAN. The PAN's first executive committee and committees on political action and doctrine also had former Catholic student activists, including Luis Calderón Vega, the father of Felipe Calderón, who was elected President of Mexico in 2006.[15] The PAN's “Doctrine of National Action” was strongly influenced by Catholic social doctrine articulated in Rerum novarum (1891) and Quadragesimo anno (1931) and rejected Marxist models of class warfare.[16] The PAN's newspaper, La Nación was founded by another former UNEC member, Carlos Séptien García.[17]

Efraín González Luna, a former member of the Mexican Catholic Student Union (Unión Nacional de Estudiantes Católicos) (UNEC), a long-time militant Catholic and practicing lawyer from Guadalajara, helped broker the party's informal alliance with the Catholic Church. The relationship between the PAN and the Catholic Church was not without tension. The party's founder Gómez Morín was leery of clerical oversight of the party, although its members were mainly urban Catholic professionals and businessmen. For its part, the Church hierarchy did not want to identify itself with a particular political party, since the Constitution of 1917 forbade it. In the 1950s, the PAN, which had been seen to be Catholic in its makeup, became more ideologically secular.[17]

The PAN initially was a party of “civic example”, an independent loyal opposition that generally did not win elections at any level. However, in the 1980s it began a transformation to a political power, beginning at the local and state levels in the North of Mexico.[18] A split in the PAN occurred in 1977, with the pro-Catholic faction and the more secular wing splitting. The PAN had updated its positions following Vatican II, toward a greater affinity for the poor; however, more traditional Catholics were critical of that stance and nonreligious groups were also in opposition, since they wanted the party to be less explicitly Catholic and draw in more urban professionals and business groups, who would vote for a nonreligious opposition party. The conflict came to a head, and in 1977 the progressive Catholic wing left the party.[19] The party ran no presidential candidate in 1976.

The PAN had strength in Northern Mexico and its candidates had won elections earlier on, but these victories were small in comparison to those of the Institutional Revolutionary Party. In 1946, PAN members Miguel Ramírez Munguía (Tacámbaro, Michoacán), Juan Gutiérrez Lascurain (Federal District), Antonio L. Rodríguez (Nuevo León) and Aquiles Elorduy García (Aguascalientes) became the first four federal deputies from the opposition in post-revolutionary Mexico. The following year Manuel Torres Serranía from Quiroga, Michoacán became the party's first municipal president and Alfonso Hernández Sánchez (from Zamora, Michoacán) its first state deputy.[20] In 1962, Rosario Alcalá (Aguascalientes) became the first female candidate for state governor and two years later Florentina Villalobos Chaparro (Parral, Chihuahua) became the first female federal deputy. In 1967 Norma Villarreal de Zambrano (San Pedro Garza García, Nuevo León) became the first female municipal president.

Acción Juvenil official logo

Until the 1980s, the PAN was a weak opposition party that was considered pro-Catholic and pro-business, but never garnered many votes. Its strength, however, was that it was pro-democracy and pro-rule of law, so that its political profile was in contrast to the dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) that was widely and increasingly seen as corrupt. The PAN came to be viewed as viable opposition party for a wider range of voters as it became more secular and as Mexicans increasingly moved to cities. As the PAN increasingly called for end of fraud in Mexican elections, it appealed to a wider range of people.

In 1988, the newly created Assembly of Representatives of the Federal District had, for the first time, members of the PAN. In 1989, Ernesto Ruffo Appel (Baja California) became the first opposition governor. Two years later, his future successor in the Baja California government, Héctor Terán Terán, became the first federal senator from the PAN. From 1992 to 2000, PAN candidates won the elections for governorships in Guanajuato, Chihuahua, Jalisco, Querétaro, Nuevo León, Aguascalientes, Yucatán and Morelos.[20]

21st century

Defeating the PRI to presidency

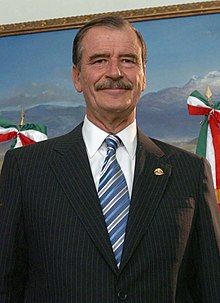

Vicente Fox, first PANista to be elected president of Mexico (2000-06), ended more than 70 years of PRI rule.

In the 2000 presidential elections, the candidate of the Alianza por el cambio ("Alliance for Change"), formed by the PAN and the Ecologist Green Party of Mexico (PVEM), Vicente Fox Quesada won 42.5% of the popular vote and was elected president of Mexico. Fox was the first opposition candidate to defeat the candidate of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and its precursors after 71 years. It was a significant victory not only for the PAN, but Mexican democracy.

In the senate elections of the same date, the Alliance won 46 out of 128 seats in the Senate. The Alliance broke off the following year and the PVEM has since participated together with the PRI in most elections.

Felipe Calderón, President of Mexico (2006-12)

PRI

PAN

PRD

PMC

PVEM

In the 2003 mid-term elections, the party won 30.74% of the popular vote and 153 out of 500 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. In 2003, the PAN lost the governorship of Nuevo León to the PRI and, the following year, failed to win back the state of Chihuahua from the PRI. Coupled with a bitterly fought election in Colima that was cancelled and later re-run, these developments were interpreted by some political analysts to be a significant rejection of the PAN in advance of the 2006 presidential election. In contrast, 2004 did see the PAN win for the first time in Tlaxcala, in a state that would not normally be considered PAN territory, although its candidate was a member of the PRI until a few months before the elections. It also managed to hold on to Querétaro (by a mere 3% margin against the PRI) and Aguascalientes (although in 2007, it lost most of the municipalities and the local Congress to the PRI). However, in 2005 the PAN lost the elections for the state government of Mexico State and Nayarit to the PRI. The former was considered one of the most important elections in the country because of the number of voters involved, which is higher than the elections for head of government of the Federal District. (See: 2003 Mexican elections, 2004 Mexican elections and 2005 Mexican elections for results.)

Significantly in the 2006 presidential election in 2006, the PAN candidate Felipe Calderón was elected to succeed Vicente Fox. Calderón was the son of one of the founders of the PAN, and was himself a former party president. He was selected as the PAN's candidate, after beating his opponents Santiago Creel (Secretary of the Interior during Fox's term) and Alberto Cárdenas (former governor of Jalisco) in every voting round in the party primaries. On July 2, 2006, Felipe Calderón secured a plurality of the votes cast. Finishing less than one percent behind was Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who challenged the results of the election on possible grounds of electoral fraud. In addition to the presidency, the PAN won 206 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 52 in the Senate, securing it the largest single party blocs in both houses.

In 2007, the PAN lost the governorship and the majority in the state congress of Yucatán to the PRI as well as the municipal presidency of Aguascalientes, but kept both the governorship and the majority in the state congress of Baja California. The PRI also obtained more municipal presidents and local congresspeople in Chihuahua, Durango, Zacatecas, Aguascalientes, Chiapas and Oaxaca. The PRD obtained more posts than the PAN in Zacatecas, Chiapas and Oaxaca.

In 2009, the PAN held 33 seats in the Senate and 142 seats in the Chamber of deputies.[11]

Return of the PRI to presidency

In 2012, the PAN lost the Presidential Election to Enrique Peña Nieto of the PRI. They also won 38 seats in the Senate (a gain of 3 seats), and 114 seats in the Chamber of Deputies (a loss of 28 seats).[11] The government of president of Mexico Enrique Peña Nieto (EPN) has faced multiple scandals, and allegations of corruption. Reforma who has run a surveys of presidential approval since 1995, revealed EPN had received a mere 12% approval rating, the lowest since they started to survey for presidential approval. The second lowest approval was for the Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000), also from the PRI. It also revealed that both presidents elected from National Action Party (PAN), Vicente Fox (2000-2006) and Felipe Calderon (2006-2012), both had higher presidential approvals than the PRI presidents.[21]

Ideology

The PAN has been linked to a conservative stance in Mexican politics since its inception, but the party does not consider itself a fundamentally conservative party. The party ideology, at least in principle, is that of "National Action" which rejects a fundamental adherence to left- or right-wing politics or policies, instead requiring the adoption of such policies as correspond to the problems faced by the nation at any given moment. Thus both right- and left-wing policies may be considered equally carefully in formulation of national policy.

This theory of National Action politics, rejecting a fundamental adherence to right or left, is held within a strongly Christian context, and falls under the umbrella of Christian democracy.[citation needed]

The party theory was largely developed by early figures such as Gómez Morín and his associates. However, some observers consider the PAN claim to National Action politics to be weakened by the apparent persistent predominance of conservatism in PAN policy in practice. The PAN has similarities with Europe and Latin America's Christian democratic parties.

Economic policies

The PAN currently occupies the right of Mexico's political spectrum, advocating free enterprise, pragmatism, small government, privatization and libertarian reforms as well. The PAN is a member of the Christian Democrat Organization of America. In general, PAN claims to support free enterprise and thus free trade agreements.[citation needed]

Social policies

Abortion

Carlos Abascal, secretary of the interior in the latter part of the Fox administration, called emergency contraception a "weapon of mass destruction" in July 2005.[22] It was during Fox's term, however, that the "morning-after" pill was legalized, even though the Church had condemned the use of these kind of pills, calling them "abortion pills".

The PAN produced a television spot against state-financed abortion, one that features popular comedian Chespirito (who was also featured on a TV spot promoting Vicente Fox in the 2000 presidential elections) and a second one that accuses the PRI and PRD of wanting to kill the unborn.[23] After the abortion bill, which made abortion available, anonymous, and free or government-paid, was approved at the local legislature, the PAN requested the Human Rights Commission of the Federal District (CDHDF) to enact actions on the unconstitutionality of the measure, the CDHDF rejected the request as it found no basis of unconstitutionality.[24] After unsuccessfully appealing to unconstitutionality, the PAN declared that it may request the remotion of Emilio Álvarez Icaza, the president of the Human Rights Commission of the Federal District, for his lack of moral quality.[25] The PAN, with the members of the Association of Catholic Lawyers, gathered signatures and turned them in to the Federal District Electoral Institute (IEDF) to void the abortion bill and force a referendum,[26] which was also rejected by the IEDF. In May 2007, the PAN started a campaign to encourage rejections to perform abortion amongst doctors in the Federal District based on conscience.[27]

Opposition to same-sex unions in Mexico

The PAN has opposed measures to establish civil unions in Mexico City and Coahuila. On November 9, 2006, the government of the Federal District approved the first law establishing civil unions in Mexico. The members of the PAN, and a member of New Alliance were the only legislators that voted against it.[28]

The same year, the local legislature of Coahuila approved the law of civil unions to which the PAN also opposed.[29] The PAN also lodged an unconstitutionality plea before the Supreme Court of Justice of the State of Coahuila, alleging that the constitution has vowed to protect the institution of the family.[30]

Guillermo Bustamente Manilla, a member of the PAN and the president of the National Parents Union (UNPF) is the father of Guillermo Bustamante Artasánchez, a law director of the Secretary of the Interior, Carlos Abascal, during Fox's presidency and worked in the Calderón administration against abortion and same-sex civil unions.[31] He called the latter as "anti-natural."[32] He has publicly asked voters not to cast votes for "abortionist" parties and those who are in favor of homosexual relationships.[33]

Party Presidents

Manuel Gómez Morín 1939-1949- Juan Gutiérrez Lascuráin 1949-1956

- Alfonso Ituarte Servín 1956-1958

- José González Torres 1958-1962

Adolfo Christlieb Ibarrola 1962-1968[34]- Ignacio Limón Maurer 1968-1969

- Manuel González Hinojosa 1969-1972

- José Ángel Conchelo Dávila 1972-1975

- Efraín González Morfín 19751

- Raúl González Schmall 1975 (interim)

- Manuel González Hinojosa 1975-1978

- Avel Vicencio Tovar 1978-1984

Pablo Emilio Madero 1984-1987

Luis H. Álvarez 1987-1993

Carlos Castillo Peraza 1993-1996

Felipe Calderón Hinojosa 1996-1999

Luis Felipe Bravo Mena 1999-2005

Manuel Espino Barrientos 2005-2007

Germán Martínez Cázares 2007-2009- César Nava Vázquez 2009-2010

Gustavo Madero Muñoz 2010-2014- Cecilia Romero Castillo 2014

Ricardo Anaya Cortés 2014–2015

Gustavo Madero Muñoz 2015

Ricardo Anaya Cortés 2015–20171

Damián Zepeda Vidales 2017-2018

Marcelo Torres Cofiño 2018

Marko Antonio Cortés Mendoza 2018–present

1.- Resigned to run for president

Electoral history

Presidential elections

| Election year | Candidate | # votes | % vote | Result | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1952 | Efraín González Luna | 285,555 | 7.8 | ||

1958 | Luis H. Álvarez | 705,303 | 9.4 | ||

1964 | José González Torres | 1,034,337 | 11.0 | ||

1970 | Efraín González Morfín | 1,945,070 | 14.0 | ||

1976 | No Candidate | null | null | ||

1982 | Pablo Emilio Madero | 3,700,045 | 16.4 | ||

1988 | Manuel Clouthier | 3,208,584 | 16.8 | ||

1994 | Diego Fernández de Cevallos | 9,146,841 | 25.9 | ||

2000 | Vicente Fox | 15,989,636 | 42.5 | Coalition: Alliance for Change | |

2006 | Felipe Calderón | 15,000,284 | 35.8 | ||

2012 | Josefina Vázquez Mota | 12,786,647 | 25.4 | ||

2018 | Ricardo Anaya | 12,609,472 | 22.3 | Coalition: Por México al Frente |

Congressional elections

Chamber of Deputies

| Election year | Constituency | PR | # of seats | Position | Presidency | Note | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| votes | % | votes | % | ||||||

1946 | 51,312 | 2.2 | 4 / 147 | Minority | Miguel Alemán Valdés | ||||

1952 | 301,986 | 8.3 | 5 / 161 | Minority | Adolfo Ruiz Cortines | ||||

1958 | 749,519 | 10.2 | 6 / 162 | Minority | Adolfo López Mateos | ||||

1964 | 1,042,396 | 11.5 | 20 / 210 | Minority | Gustavo Díaz Ordaz | ||||

1970 | 1,893,289 | 14.2 | 20 / 213 | Minority | Luis Echeverría Álvarez | ||||

1976 | 1,358,403 | 9.0 | 20 / 237 | Minority | José López Portillo | ||||

1982 | 3,663,846 | 17.5 | 51 / 400 | Minority | Miguel de la Madrid | ||||

1988 | 3,276,824 | 18.0 | 101 / 500 | Minority | Carlos Salinas de Gortari | ||||

1994 | 8,664,834 | 25.8 | 8,833,468 | 25.8 | 119 / 500 | Minority | Ernesto Zedillo | ||

1997 | 7,696,197 | 25.9 | 7,792,290 | 25.9 | 121 / 500 | Minority | Ernesto Zedillo | ||

2000 | 14,212,032 | 38.2 | 14,321,975 | 38.3 | 223 / 500 | Minority | Vicente Fox | Coalition: Alliance for Change | |

2003 | 8,189,699 | 30.7 | 8,219,649 | 30.7 | 151 / 500 | Minority | Vicente Fox | ||

2006 | 13,753,633 | 33.4 | 13,845,121 | 33.4 | 206 / 500 | Minority | Felipe Calderón | ||

2009 | 9,679,435 | 28.0 | 9,714,181 | 28.0 | 143 / 500 | Minority | Felipe Calderón | ||

2012 | 12,895,902 | 25.9 | 12,971,363 | 25.9 | 114 / 500 | Minority | Enrique Peña Nieto | ||

2015 | 8,346,846 | 22.06 | 8,379,270 | 22.06 | 108 / 500 | Minority | Enrique Peña Nieto | ||

2018 | 79 / 500 | Minority | Andrés Manuel López Obrador | Coalition: For Mexico to the Front | |||||

Senate elections

| Election year | Constituency | PR | # of seats | Position | Presidency | Note | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| votes | % | votes | % | ||||||

1994 | 8,805,038 | 25.7 | 25 / 128 | Minority | Ernesto Zedillo | ||||

1997 | 7,880,966 | 26.1 | 33 / 128 | Minority | Ernesto Zedillo | ||||

2000 | 14,208,973 | 38.1 | 14,339,963 | 38.2 | 60 / 128 | Minority | Vicente Fox | Coalition: Alliance for Change | |

2006 | 13,889,159 | 33.5 | 14,035,503 | 33.6 | 52 / 128 | Minority | Felipe Calderón | ||

2012 | 13,126,478 | 26.3 | 13,245,088 | 26.3 | 38 / 128 | Minority | Enrique Peña Nieto | ||

2018 | 22 / 128 | Minority | Andrés Manuel López Obrador | Coalition: For Mexico to the Front | |||||

Bibliography

- Chand, Vikram K. Mexico's Political Awakening, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press 2001.

- Espinosa, David. Jesuit Student Groups, the Universidad Iberoamericana, and Political Resistance in Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2014.

Loaeza, Soledad. El Partido de Acción Nacional: La larga marcha, 1939-1994: Oposición leal y partido de protesta. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económico 1999.- Loaeza, Soledad. "Partido de Acción Nacional." In Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2, pp. 1048–1052. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- Mabry, Donald J. Mexico's Acción Nacional: A Catholic Alternative to Revolution. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press 1973.

- Nuncio, Abraham. El PAN: Alternativa de poder o instrumento de la oligarquía empresarial. Mexico: Editorial Nuevo Imagen 1986.

- Von Sauer, Franz A. The Alienated "Loyal" Opposition: Mexico's Partido de Acción Nacional. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1974.

- Ward, Peter. "Policy Making and Policy Implementation among Non-PRI Government: The PAN in Ciudad Juárez and in Chihuahua." In Victoria E. Rodríguez and Peter M. Ward, Opposition Government in Mexico pp. 135–52. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1995.

See also

- National Action Party Jalisco

References

^ Shirk, David A. (2005). Mexico's New Politics: The PAN and Democratic Change. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 57..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ O'Toole, Gavin (2007). Politics Latin America. Pearson Education. p. 383.

^ Cook, Rhodes (2004). The Presidential Nominating Process: A Place for Us?. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7425-2594-8.

^ Loaeza, Soledad (2003). The National Action Party (PAN): From the Fringes of the Political System to the Heart of Change. Christian Democracy in Latin America: Electoral Competition and Regime Conflicts. Stanford University Press. p. 196.

^ Bensusán, Graciela; Middlebrook, Kevin J. (2012). Organized Labor and Politics in Mexico. The Oxford Handbook of Mexican Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 347.

^ Wiltse, Evren Çelik (2007). Globalization and Mexico. Globalization: Universal trends, regional implications. University Press of New England. p. 214.

^ Cornelius, Wayne A. (2002). Mexicans Would Not Be Bought, Coerced. The Mexico Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. p. 684.

^ Adler-Lomnitz, Larissa; Salazar-Elena, Rodrigo; Adler, Ilya (2010). Symbolism and Ritual in a One-Party Regime: Unveiling Mexico's Political Culture. University of Arizona Press. p. 293.

^ Mazza, Jacqueline (2001). Don't Disturb the Neighbors: The United States and Democracy in Mexico, 1980-1995. Routledge. p. 9.

^ Needler, Martin C. (1995). Mexican Politics: The Containment of Conflict (3rd ed.). Praeger Publishers. p. 61.

^ abc Seelke, Claire. "Mexico's 2012 Elections" (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

^ Soledad Loaeza, "Partido de Acción Nacional (PAN)" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 2, p. 1048. Chicago: Fitzroy and Dearborn 1997.

^ Vikram K. Chand, Mexico’s Political Awakening. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press 2001.

^ Loaeza, "Partido de Acción Nacional", p. 1049.

^ Espinosa, Jesuit Student Groups, p. 73

^ Espinosa, Jesuit Student Groups, p. 73.

^ ab Espinosa, Jesuit Student Groups, p. 73.

^ Vikram K. Chand, Mexico’s Political Awakening, see especially chapter 3 “The Transformation of Mexico’s National Action Party (PAN): From Civic Example to Political Power.”

^ Loaeza, "Partido de Acción Nacional", p. 1051.

^ ab History of the PAN. PAN official website.

^ "Why Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto is so unpopular".

^ "PALABRAS DEL SECRETARIO DE GOBERNACIÓN, CARLOS ABASCAL CARRANZA, DURANTE EL DESAYUNO CON DIRECTIVOS DEL CENTRO DE REHABILITACIÓN INTEGRAL TELETON (CRIT) TLALNEPANTLA Y DIRECTIVOS DE LOS MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN" (in Spanish). Secretaría de Gobernación. 19 July 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

^ "Difunde PAN spot Vs. aborto en Internet". Frontera (in Spanish). 26 April 2007. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008.

^ "Improcedente, acción de inconstitucionalidad contra aborto: CDHDF". La Crónica (in Spanish). 11 May 2007.

^ "El PAN-DF, molesto porque Álvarez Icaza apoyó la despenalización, ahora pide la cabeza del ombudsman". La Crónica (in Spanish). 5 May 2007.

^ "Invalida IEDF solicitud de referendum sobre el aborto". El Sol de México (in Spanish). 7 May 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

^ "Inicia PAN-DF campaña contra el aborto en hospitals". La Jornada (in Spanish). 8 May 2007. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007.

^ "Aprueban la Ley de Sociedades de Convivencia". El Universal (in Spanish). November 10, 2006.

^ "New law propels gay rights in Mexico - (Coahuila moves boldly with civil unions as nation watches)". Free Republic. March 5, 2007.

^ "Legisladores mexicanos presentan recurso ante la Suprema Corte de Justicia contra la ley de uniones civiles". Hispavista (in Spanish). 11 February 2007. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007.

^ "Calderón, cómplice del clero". Proceso (in Spanish). 24 April 2007.

^ "Mexico City's law on civil unions draws mixed reaction". Noticias de Oaxaca. March 16, 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

^ "Padres de familia mexicanos piden no votar por partidos abortistas". ACI Prensa (in Spanish). 30 April 2007.

^ "Biography of Adolfo Christlieb Ibarrola". Memoria Política de México.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Action Party. |

(in Spanish) Official website of the National Action Party