Neafie & Levy

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP Former type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Shipbuilding |

| Fate | Bankruptcy |

| Founded | 1844 |

| Defunct | 1907 |

| Headquarters | Kensington, Philadelphia, US |

| Products | Iron and steel steamships, marine engines, propellers, industrial equipment |

| Total assets | $1,000,000 (1870) |

Number of employees | 300 (1870) |

Neafie, Levy & Co., commonly known as Neafie & Levy, was a Philadelphia shipbuilding and engineering firm that existed from the middle of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century. Described as America's "first specialist marine engineers",[1] Neafie & Levy was probably the first company in the United States to combine the building of iron ships with the manufacture of steam engines to power them.[2] The company was also the largest supplier of screw propellers to other North American shipbuilding firms in its early years, and at its peak in the early 1870s was Philadelphia's busiest and most heavily capitalized shipbuilder.

Following the death of one of its proprietors, John P. Levy, in 1867, the company grew more conservative and eventually became a "niche" shipbuilder of smaller high quality vessels such as steam yachts and tugs. A few years after the retirement and death of its founder and longstanding manager Jacob Neafie in 1898, the company folded through a combination of indifferent management, bad publicity and unprofitable US Navy contracts.

Neafie & Levy's 1907 ferry Yankee, seen here in its heyday, is still operational today

Amongst the more notable vessels built by the company were the U.S. Navy's first submarine, the USS Alligator in 1862, and the Navy's first destroyer, USS Bainbridge (DD-1), in 1902.[3] Several of its vessels, such as the tugboats Jupiter and Tuff-E-Nuff and the ferry Yankee, are still operational today more than a hundred years after first entering service. In all, the company built more than 300 ships and 1,100 marine steam engines during the course of its 63-year history,[4] in addition to its non-marine manufactures, which included refrigeration and sugar refining equipment.

Contents

1 Early years

2 Innovation and leadership, 1850–1870

2.1 The Civil War

2.1.1 Submarine Alligator

2.2 Postwar slump and recovery

3 Conservatism, 1870–1880s

3.1 1870s slump and 1880s recovery

3.2 1883 strike and aftermath

4 A niche shipbuilder, 1880s–1890s

5 Naval contracts and bankruptcy, 1900s

6 Fate of the shipyard

7 Footnotes

8 Recurring references

Early years

The dominant figure in the company for most of its existence was Jacob G. Neafie. Born in New Jersey on Christmas Day 1815, Neafie served his apprenticeship as a machinist in New York before joining the Philadelphian shipbuilding firm of Thomas Holloway in 1832, where he gained experience in shipbuilding and reportedly took an interest in the new technology of screw propulsion.

After leaving Holloway to establish his own small business in 1838, Neafie joined with two other Philadelphian mechanics, Thomas Reaney and William Smith, to found the firm of Reaney, Neafie & Smith in 1844. The partners quickly established a plant on 7 acres (28,000 m2) of waterfront property along the Delaware River, and named the new plant the Penn Steam Engine and Boiler Works (thus giving the company its most often used alternative name, Penn Works).

Though originally established to build "fire engines, boilers and stationary steam engines",[5] the firm quickly added shipbuilding, constructing its first vessel, the 65-ton steamboat Conestoga, in its first year of operation, and the 99-ton Barclay the following year.[6] That same year, Smith died, and a new partner, Captain John P. Levy, joined the firm, which was then renamed Reaney, Neafie & Levy. Levy, a wealthy man with connections in government and industry, was an important addition to the company. His most significant early contribution was to persuade a local Philadelphian inventor and steamboat operator, Richard Loper, to license his patent for a unique type of curved propeller, and Reaney, Neafie & Levy were soon to acquire a reputation as specialist propeller makers. In 1859, Thomas Reaney left the firm to establish his own shipbuilding company, Reaney & Son (later Reaney, Son & Archbold), and Reaney, Neafie & Levy became Neafie, Levy & Co..[7]

Innovation and leadership, 1850–1870

Through the 1840s, Neafie & Levy was primarily a manufacturer and supplier of marine steam engines and screw propellers to builders of wooden ships, such as Birely, Hillman & Streaker and William Cramp & Sons. In the early 1850s however, Neafie & Levy began to experiment with iron shipbuilding as a corollary to its propeller-making business.

The screw propeller had a number of advantages over the paddlewheel, but it also had disadvantages. Amongst these were the vibration levels caused by higher RPM propeller engines, which loosened bolts on wooden ships, and the tendency for propeller shafts to break due to the phenomenon of "hogging" — the slight flexing of a ship's hull as waves pass beneath it. Since iron vessels were stronger and less prone to hogging, and were also less affected by vibration, it made sense to combine propeller technology with iron hulls.

Neafie & Levy built its first iron ship in 1855. By 1860, it had become one of America's leading iron shipbuilding firms, with assets of $300,000, annual output of $368,000, and a workforce of 300.[8] It had also become America's largest supplier of screw propellers, which grew to be so popular with the shipping firms on North America's Great Lakes that the company's curved propeller was dubbed the "Philadelphia wheel".[9]

The Civil War

The American Civil War (1861–65) was an economic boom period for American shipbuilders. Over the course of the war, the U.S. Navy requisitioned more than a million tons of shipping from commercial companies, and those companies were then obliged to return to the shipbuilding industry to replace the ships sold to the Navy. In addition, the Navy itself placed contracts with shipbuilders for the construction of warships and other tonnage, such as supply ships and troop transports, sparking a speculative boom in which private firms placed more shipping contracts in hopes of selling them to the government at inflated wartime prices.

Neafie & Levy's experience with the Navy though, was to be less than agreeable. The company had supplied the engines for the USS Pawnee just prior to the war but the Navy Department was dissatisfied with the engine's performance and refused to make full payment, prompting Jacob Neafie to vow never to take another Navy contract. Apart from the construction of the experimental submarine USS Alligator in 1861, Neafie stuck to his vow and repudiated Navy contracts for the remainder of the war. His company still benefited from the boom in commercial shipping however, and made a substantial contribution to the war effort, supplying more than 120 engines for warships and other government vessels built at other yards.[10] At its wartime peak, the company employed 800 workers.[11]

Submarine Alligator

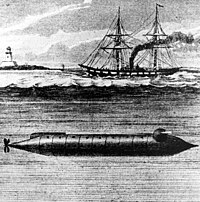

Contemporary artist's impression of the USS Alligator

In the autumn of 1861, the Navy asked Neafie and Levy to construct a small submersible designed by the French engineer Brutus DeVilleroi, who was prepared to act as a supervisor during construction. The vessel was designed with a special airlock through which a diver could attach mines to a ship's hull, and was intended for use against the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia, for which the U.S. Navy had no defense.

The contract with Neafie & Levy was signed in November 1861, and the submersible was expected to be completed within forty days, but difficulties with the design along with the departure of DeVilleroi delayed the ship's delivery by about six months, by which time the submersible's original purpose had been obviated. The Navy then attempted to use the submersible, now named Alligator, for another mission off Charleston, South Carolina, but while being towed there it sank during a storm on the night of 2 April 1863. The Alligator however, retains the distinction of being the first submarine to see service with the US Navy.[12][13]

Postwar slump and recovery

In 1865, the Civil War came to an end with the Union victory, and the wartime conditions that had created a shipbuilding boom now gave way to a corresponding slump. The Navy conducted an auction of hundreds of unwanted ships, flooding the market and leaving shipyards with no work. Decline in the need for domestic shipping caused by the extension of railroads to the South, along with the growing economic independence of the West, also contributed to the shipbuilding recession.

The immediate response of Neafie & Levy, as at many other shipyards, was to slash its workforce to the bone. It then joined with William Cramp & Sons in 1866 to create a small subsidiary ferryboat company, for the operation of which Cramp built a ferry called the Shackamaxon, while Neafie & Levy supplied the engines. The company's only other work in this period was for the production of a few towboats and some ship repair work.

In 1867, Neafie & Levy suffered a major setback with the death of John P. Levy, whose management position was then filled by his heir Edmund L. Levy. With John Levy's death, the company appears to have lost much of its original dynamism, as Jacob Neafie's caution and conservatism increasingly became the dominant factor in its management. This decline would not become evident for some years however.

By 1870 the slump had come to an end, and the years 1870–71 were amongst Neafie & Levy's most productive. In this two-year period, Neafie & Levy was Philadelphia's busiest shipyard, building 27 vessels and supplying the engines for many others, including those for the 1,200-ton Cramp steamer Clyde, built for the Clyde Line.[14]

Conservatism, 1870–1880s

The year 1871 however, also brought developments which signalled Neafie & Levy's eventual departure from the front rank of American shipbuilders. In this year, Cramp & Sons built its first marine engine, and henceforth was to purchase no more engines from Neafie & Levy, depriving the latter of a principal customer. Moreover, Cramp constructed a large dry dock which enabled it to enter the lucrative hull repair business. Jacob Neafie did not follow suit, preferring to rely upon his existing business model of building smaller iron vessels and supplying engines to builders of wooden ships. By 1880, although Neafie & Levy was still Philadelphia's most heavily capitalized firm with a million dollars in assets, its return on investment (ROI) was only 7.1% compared to that of Cramp with an ROI in excess of 15%. Moreover, Cramp's capitalization was not far behind at $750,000, but it employed 2,300 workers compared to Neafie & Levy's 500, and its output was more than 2½ times greater. A substantial part of the difference was due to the Cramp dry dock.[15]

1870s slump and 1880s recovery

1873 marked another prolonged downturn in the industry, triggered by the 1873 financial panic. All American shipyards struggled, and the nadir for Neafie & Levy came in 1877, when not a single ship was launched. To keep their businesses solvent, shipyards at this time diversified into other areas—in Neafie & Levy's case, into the manufacture of refrigeration equipment. Shipyards also petitioned the government for Navy contracts, and Neafie & Levy was able to secure a modest $35,000 for Navy ship repairs in these years, which included the completion of the gunboat USS Quinnebaug.[16]

The slump in the shipbuilding industry finally came to an end in 1880, when new ship orders, generated by demand for foreign produce such as sugar, wool and coffee, began to arrive. Neafie & Levy contracted for freighters and tugs, in particular for the wooden steamships Maracaibo and Fortuano for the Red D Line's Venezuelan coffee imports. Reconstruction of the American South following the Civil War was also creating new demand, and in the same year Neafie & Levy also contracted for the Clyde steamer Delaware for the southern cotton trade. Further contracts came in the 1880s with the patronage of Philadelphia's Lewis Luckenbach Towing Company, which needed barges and powerful tugboats for its novel transport method of tandem barge towing, and which contracted with Neafie & Levy for such vessels as the 200-ton tugboat Ocean King, built in 1884.

Demand for vessels in the early 1880s was strong enough to motivate shipyards to upgrade their facilities, although once again Neafie & Levy chose to make only modest improvements. In 1882, the company booked orders for five small iron vessels and built engines for another fifteen wooden steamers. Demand was also driving the creation of new shipbuilding companies, such as the short-lived American Shipbuilding Company, which subcontracted vessels to Neafie & Levy including the 2,728-gross-ton steamer Chatham and the collier Frostburg.[17]

1883 strike and aftermath

In 1883, more than 500 ships' carpenters walked out of shipyards in Philadelphia and Camden, New Jersey in an attempt to gain a wage increase. They failed to shut down the yards however, since they had not invited metal tradesmen to join the strike.

The proprietors of the shipyards resolved to act in unison against the strikers, and did so by introducing strikebreakers and declaring an end to the closed shop system. After seven weeks of bitter standoff, the strikers were forced to return to work under the new open shop system, a system that would prevail until World War I.

By 1884 the brief upturn in shipbuilding was over, and the industry experienced another slump. Shipping companies responded, as always, by slashing their workforce — Cramp from 1,800 to 800 men, and Neafie & Levy from 300 to just 50.[18]

A niche shipbuilder, 1880s–1890s

J. P. Morgan's spectacular yacht Corsair, built by Neafie & Levy in 1890

In the latter half of the 1880s, the larger shipyards turned to government contracts for assistance in weathering the slump, while the government itself was keen to expand the Navy. Smaller Philadelphia shipyards like Neafie & Levy, however—mindful both of the rigorous conditions placed on Navy contracts, and of the recent example of an established shipyard bankrupted by such a contract—preferred other solutions.

Neafie & Levy refused to bid for Navy contracts in 1886–87, relying instead on private contracts for smaller vessels of under 1,500 tons—such as yachts, tugs, ferries and barges—demand for which had begun to increase after 1887. Between 1888 and 1893, Neafie & Levy built 28 small iron steamships and thirty engines for larger vessels built at other yards. Its major customers included the New York, Lake Erie & Western Railroad, which required tugs and ferryboats for the expansion of its harbor service fleet.

In addition, Neafie & Levy built some small warships and sugar-processing equipment for South American customers, a niche the company had filled since the 1870s. Business was solid enough for the company to invest in further expansion of its plant, with new offices, drafting rooms and workshops. To help pay for this expansion, the company went public, and formally became the Neafie & Levy Ship and Engine Building Company. The proprietors however, retained the majority of shares and thus control of the business.

The most spectacular vessel built by the company in this period was the steam yacht Corsair II for the millionaire businessman J. Pierpont Morgan. Designed by Morgan's friend J. Frederic Tams who was told to spare no expense, the lavishly outfitted vessel was the world's largest pleasure ship upon launch in 1890.[19]

USS St. Louis off Boston, 1917

In 1898, Jacob Neafie, who had successfully steered his company through the most turbulent half-century in American shipbuilding history, retired from the business at the age of 82 and died a few days later. His will assigned the business to a trustee, a real estate broker with little shipbuilding experience named Matthias Seddinger, who was to manage the estate on behalf of Neafie's daughter Mary. Seddinger, now the firm's nominal President, passed managerial control to the new vice president of the company, a marine engineer named Sommers N. Smith.

Repudiating Jacob Neafie's longstanding avoidance of Naval contracts, Smith sooned booked contracts for three US Navy destroyers—the Navy's first vessels of the type—the Bainbridge, Barry and Chauncey. He also booked contracts for the protected cruisers USS Denver and USS St. Louis.

Smith quickly ran into trouble with the new Navy contracts. Firstly, his bid of $374,000 per ship for the three destroyers proved too low. Delays in delivery of specialty steel for the ships meant postponement of Navy payments which were made on a milestone basis. Furthermore, the Navy design proved too ambitious, as the ships' hulls were too light to absorb vibrations caused by the powerful engines. As a result, the USS Bainbridge was subjected to more Navy trials than any other warship, and by the time the vessels were finally delivered in 1902, Smith had lost a total of $180,000 on the three destroyer contracts.

Similarly, delays in steel delivery for the USS St. Louis resulted in deferments of payment by the Navy, forcing Smith to obtain loans to pay for the ship's completion. At around the same time, a boiler exploded on a ship recently completed by the company, the river steamer City of Trenton, killing 24 passengers in one of the Delaware River's worst accidents.[20] Relatives of the passengers sued, and though the company was eventually exonerated, its reputation was harmed in the meantime and business slowed. By November 1903 the company was unable to service its debts.

Initially, a group of benevolent creditors placed the company into receivership, believing it just needed some time to trade its way out of difficulty. Unfortunately, the group appointed Sommers N. Smith himself as receiver, and when it was discovered that Seddinger and Smith had awarded themselves a large dividend out of capital in the midst of the company's troubles, as well as engaging in fraudulent bookkeeping, the remaining creditors' confidence was shaken. Seddinger and Smith were removed from their positions, and a more competent receiver appointed, but the latter was unable to persuade the creditors to make the necessary investments to revive the company's fortunes, and in May 1908 the Neafie & Levy plant was sold for the sum of only $50,000.

The company's last vessel, the steel tug Adriatic, was delivered in September 1908, after which the new owners discontinued shipbuilding operations.[21]

Fate of the shipyard

Following the delivery of Adriatic, wreckers tore down the shipyard's buildings and dismantled the ship's berths, and the premises was sold to the Immigration Service, which erected a quarantine station in its place.[4] In 1920, the site was resold to the Philadelphia Electric Company, which built the Delaware Power Station there. The power station operated until 2004 when it was shut down. The present owners, Exelon Corporation, have said they currently have no plans for the site, but are retaining it in hopes of one day returning it to electricity generation.[22]

Footnotes

^ Dawson, Andrew (2004): Lives of the Philadelphia Engineers: Capital, Class, and Revolution, 1830–1890, Ashgate Publishing, p. 36. ISBN 978-0-7546-3396-9.

^ Tyler, p.7.

^ USS Bainbridge (DD-1), Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

^ ab Heinrich, p. 151.

^ Heinrich p. 19.

^ Tyler, p. 7.

^ Heinrich, pp. 19–20.

^ Heinrich p. 20.

^ Neafie & Levy, Navy and Marine Living History Association, reprinted from The Neafie & Levy Ship and Engine Building Company (Penn Works), published by Ulysses Grant Duffield, New York (Franklin Printing Co., Philadelphia, 1896), pp. 4–9.

^ Heinrich, p. 28.

^ Story of the Alligator, Navy and Marine Living History Association.

^ Miles, Jim (2000): Forged in Fire: A History and Tour Guide of the War in the East, From Manassas to Antietam, 1861–1862, Cumberland House Publishing, ISBN 978-1-58182-089-8, p. 132.

^ Heinrich, pp. 50–54.

^ Heinrich, pp. 53–54, 74–75.

^ Heinrich, pp. 70–71.

^ Heinrich, pp. 77–84.

^ Heinrich, p. 93.

^ Heinrich, pp. 102, 105, 139.

^ Tyler, p. 99.

^ Heinrich, pp. 148–151.

^ How the Excelon (sic) Delaware power plant came to be, PlanPhilly website.

Coordinates: 39°58′6.65″N 75°7′26.12″W / 39.9685139°N 75.1239222°W / 39.9685139; -75.1239222

Recurring references

Neafie & Levy, Navy and Marine Living History Association.- Heinrich, Thomas R. (1997): Ships for the Seven Seas: Philadelphia Shipbuilding in the Age of Industrial Capitalism, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5387-7.

- Tyler, David B. (1958): The American Clyde: A History of Iron and Steel Shipbuilding on the Delaware from 1840 to World War I, University of Delaware Press, ASIN B0017WU3AW (reprinted 1992, ISBN 978-0-87413-101-7).