Circumscribed circle

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

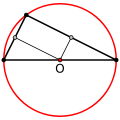

Circumscribed circle, C, and circumcenter, O, of a cyclic polygon, P

In geometry, the circumscribed circle or circumcircle of a polygon is a circle that passes through all the vertices of the polygon. The center of this circle is called the circumcenter and its radius is called the circumradius.

A polygon that has a circumscribed circle is called a cyclic polygon (sometimes a concyclic polygon, because the vertices are concyclic). All regular simple polygons, all isosceles trapezoids, all triangles and all rectangles are cyclic.

A related notion is the one of a minimum bounding circle, which is the smallest circle that completely contains the polygon within it. Not every polygon has a circumscribed circle, as the vertices of a polygon do not need to all lie on a circle, but every polygon has a unique minimum bounding circle, which may be constructed by a linear time algorithm.[2] Even if a polygon has a circumscribed circle, it may not coincide with its minimum bounding circle; for example, for an obtuse triangle, the minimum bounding circle has the longest side as diameter and does not pass through the opposite vertex.

Contents

1 Triangles

1.1 Straightedge and compass construction

1.2 Alternate construction

1.3 Circumcircle equations

1.3.1 Cartesian coordinates

1.3.2 Parametric equation

1.3.3 Trilinear and barycentric coordinates

1.3.4 Higher dimensions

1.4 Circumcenter coordinates

1.4.1 Cartesian coordinates

1.4.2 Trilinear coordinates

1.4.3 Barycentric coordinates

1.4.4 Circumcenter vector

1.4.5 Cartesian coordinates from cross- and dot-products

1.4.6 Location relative to the triangle

1.5 Angles

1.6 Triangle centers on the circumcircle of triangle ABC

1.7 Other properties

2 Cyclic quadrilaterals

3 Cyclic n-gons

3.1 Point on the circumcircle

3.2 Polygon circumscribing constant

4 See also

5 Notes

6 References

7 External links

7.1 MathWorld

7.2 Interactive

Triangles

All triangles are cyclic; i.e., every triangle has a circumscribed circle.

Straightedge and compass construction

Construction of the circumcircle (red) and the circumcenter Q (red dot)

The circumcenter of a triangle can be constructed by drawing any two of the three perpendicular bisectors. For three non-collinear points,

these two lines cannot be parallel, and the circumcenter is the point where they cross. Any point on the bisector is equidistant from the two points that it bisects, from which it follows that this point, on both bisectors, is equidistant from all three triangle vertices.

The circumradius is the distance from it to any of the three vertices.

Alternate construction

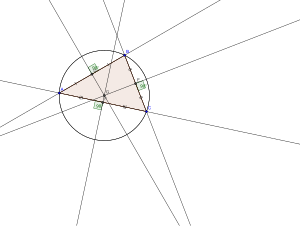

Alternate construction of the circumcenter (intersection of broken lines)

An alternate method to determine the circumcenter is to draw any two lines each one departing from one of the vertices at an angle with the common side, the common angle of departure being 90° minus the angle of the opposite vertex. (In the case of the opposite angle being obtuse, drawing a line at a negative angle means going outside the triangle.)

In coastal navigation, a triangle's circumcircle is sometimes used as a way of obtaining a position line using a sextant when no compass is available. The horizontal angle between two landmarks defines the circumcircle upon which the observer lies.

Circumcircle equations

Cartesian coordinates

In the Euclidean plane, it is possible to give explicitly an equation of the circumcircle in terms of the Cartesian coordinates of the vertices of the inscribed triangle. Suppose that

- A=(Ax,Ay)B=(Bx,By)C=(Cx,Cy)displaystyle beginalignedmathbf A &=(A_x,A_y)\mathbf B &=(B_x,B_y)\mathbf C &=(C_x,C_y)endaligned

are the coordinates of points A, B, and C. The circumcircle is then the locus of points v = (vx,vy) in the Cartesian plane satisfying the equations

- |v−u|2=r2|A−u|2=r2|B−u|2=r2|C−u|2=r2displaystyle ^2&=r^2\

guaranteeing that the points A, B, C, and v are all the same distance r from the common center u of the circle. Using the polarization identity, these equations reduce to the condition that the matrix

- [|v|2−2vx−2vy−1|A|2−2Ax−2Ay−1|B|2−2Bx−2By−1|C|2−2Cx−2Cy−1]displaystyle beginbmatrix

has a nonzero kernel. Thus the circumcircle may alternatively be described as the locus of zeros of the determinant of this matrix:

- det[|v|2vxvy1|A|2AxAy1|B|2BxBy1|C|2CxCy1]=0.displaystyle det ^2&C_x&C_y&1endbmatrix=0.

Using cofactor expansion, let

- Sx=12det[|A|2Ay1|B|2By1|C|2Cy1],Sy=12det[Ax|A|21Bx|B|21Cx|C|21],a=det[AxAy1BxBy1CxCy1],b=det[AxAy|A|2BxBy|B|2CxCy|C|2]displaystyle beginalignedS_x&=frac 12det mathbf A ,\[5pt]S_y&=frac 12det mathbf B ,\[5pt]a&=det beginbmatrixA_x&A_y&1\B_x&B_y&1\C_x&C_y&1endbmatrix,\[5pt]b&=det ^2\B_x&B_y&endaligned

we then have a|v|2 − 2Sv − b = 0 and, assuming the three points were not in a line (otherwise the circumcircle is that line that can also be seen as a generalized circle with S at infinity), |v − S/a|2 = b/a + |S|2/a2, giving the circumcenter S/a and the circumradius √b/a + |S|2/a2. A similar approach allows one to deduce the equation of the circumsphere of a tetrahedron.

Parametric equation

A unit vector perpendicular to the plane containing the circle is given by

- n^=(P2−P1)×(P3−P1)|(P2−P1)×(P3−P1)|.displaystyle widehat n=frac (P_2-P_1)times (P_3-P_1)(P_2-P_1)times (P_3-P_1).

Hence, given the radius, r, center, Pc, a point on the circle, P0 and a unit normal of the plane containing the circle, n^textstyle widehat n

- R(s)=Pc+cos(sr)(P0−Pc)+sin(sr)[n^×(P0−Pc)].displaystyle mathrm R (s)=mathrm P_c +cos left(frac mathrm s mathrm r right)(P_0-P_c)+sin left(frac mathrm s mathrm r right)left[widehat ntimes (P_0-P_c)right].

Trilinear and barycentric coordinates

An equation for the circumcircle in trilinear coordinates x : y : z is[1]:p. 199a/x + b/y + c/z = 0. An equation for the circumcircle in barycentric coordinates x : y : z is a2/x + b2/y + c2/z = 0.

The isogonal conjugate of the circumcircle is the line at infinity, given in trilinear coordinates by ax + by + cz = 0 and in barycentric coordinates by x + y + z = 0.

Higher dimensions

Additionally, the circumcircle of a triangle embedded in d dimensions can be found using a generalized method. Let A, B, and C be d-dimensional points, which form the vertices of a triangle. We start by transposing the system to place C at the origin:

- a=A−C,b=B−C.displaystyle beginalignedmathbf a &=mathbf A -mathbf C ,\mathbf b &=mathbf B -mathbf C .endaligned

The circumradius, r, is then

- r=‖a‖‖b‖‖a−b‖2‖a×b‖=‖a−b‖2sinθ=‖A−B‖2sinθ,displaystyle r=frac mathbf a -mathbf b rightmathbf a times mathbf b right=frac 2sin theta =frac left2sin theta ,

where θ is the interior angle between a and b. The circumcenter, p0, is given by

- p0=(‖a‖2b−‖b‖2a)×(a×b)2‖a×b‖2+C.displaystyle p_0=frac (leftmathbf a times mathbf b right+mathbf C .

This formula only works in three dimensions as the cross product is not defined in other dimensions, but it can be generalized to the other dimensions by replacing the cross products with following identities:

- (a×b)×c=(a⋅c)b−(b⋅c)a,a×(b×c)=(a⋅c)b−(a⋅b)c,‖a×b‖=‖a‖2‖b‖2−(a⋅b)2.displaystyle &=sqrt left.endaligned

Circumcenter coordinates

Cartesian coordinates

The Cartesian coordinates of the circumcenter U=(Ux,Uy)displaystyle U=left(U_x,U_yright)

- Ux=1D[(Ax2+Ay2)(By−Cy)+(Bx2+By2)(Cy−Ay)+(Cx2+Cy2)(Ay−By)]Uy=1D[(Ax2+Ay2)(Cx−Bx)+(Bx2+By2)(Ax−Cx)+(Cx2+Cy2)(Bx−Ax)]displaystyle beginalignedU_x&=frac 1Dleft[left(A_x^2+A_y^2right)left(B_y-C_yright)+left(B_x^2+B_y^2right)left(C_y-A_yright)+left(C_x^2+C_y^2right)left(A_y-B_yright)right]\U_y&=frac 1Dleft[left(A_x^2+A_y^2right)left(C_x-B_xright)+left(B_x^2+B_y^2right)left(A_x-C_xright)+left(C_x^2+C_y^2right)left(B_x-A_xright)right]endaligned

with

- D=2[Ax(By−Cy)+Bx(Cy−Ay)+Cx(Ay−By)].displaystyle D=2left[A_xleft(B_y-C_yright)+B_xleft(C_y-A_yright)+C_xleft(A_y-B_yright)right].,

Without loss of generality this can be expressed in a simplified form after translation of the vertex A to the origin of the Cartesian coordinate systems, i.e., when A′ = A − A = (A′x,A′y) = (0,0). In this case, the coordinates of the vertices B′ = B − A and C′ = C − A represent the vectors from vertex A′ to these vertices. Observe that this trivial translation is possible for all triangles and the circumcenter U′=(Ux′,Uy′)displaystyle U'=(U'_x,U'_y)

- Ux′=1D′[Cy′(Bx′2+By′2)−By′(Cx′2+Cy′2)],Uy′=1D′[Bx′(Cx′2+Cy′2)−Cx′(Bx′2+By′2)]displaystyle beginalignedU'_x&=frac 1D'left[C'_yleft(B'_x^2+B'_y^2right)-B'_yleft(C'_x^2+C'_y^2right)right],\U'_y&=frac 1D'left[B'_xleft(C'_x^2+C'_y^2right)-C'_xleft(B'_x^2+B'_y^2right)right]endaligned

with

- D′=2(Bx′Cy′−By′Cx′).displaystyle D'=2left(B'_xC'_y-B'_yC'_xright).,

Due to the translation of vertex A to the origin, the circumradius r can be computed as

- r=‖U′‖=Ux′2+Uy′2U'right

and the actual circumcenter of ABC follows as

- U=U′+Adisplaystyle U=U'+A

Trilinear coordinates

The circumcenter has trilinear coordinates[1]:p.19

- cos α : cos β : cos γ

where α, β, γ are the angles of the triangle.

In terms of the side lengths a, b, c, the trilinears are[2]

- a(b2+c2−a2):b(c2+a2−b2):c(a2+b2−c2).displaystyle aleft(b^2+c^2-a^2right):bleft(c^2+a^2-b^2right):cleft(a^2+b^2-c^2right).

Barycentric coordinates

The circumcenter has barycentric coordinates

a2(b2+c2−a2):b2(c2+a2−b2):c2(a2+b2−c2),displaystyle a^2left(b^2+c^2-a^2right):;b^2left(c^2+a^2-b^2right):;c^2left(a^2+b^2-c^2right),,[3]

where a, b, c are edge lengths (BC, CA, AB respectively) of the triangle.

In terms of the triangle's angles α,β,γ,displaystyle alpha ,beta ,gamma ,

- sin2α:sin2β:sin2γ.displaystyle sin 2alpha :sin 2beta :sin 2gamma .

Circumcenter vector

Since the Cartesian coordinates of any point are a weighted average of those of the vertices, with the weights being the point's barycentric coordinates normalized to sum to unity, the circumcenter vector can be written as

- U=a2(b2+c2−a2)A+b2(c2+a2−b2)B+c2(a2+b2−c2)Ca2(b2+c2−a2)+b2(c2+a2−b2)+c2(a2+b2−c2).displaystyle U=frac a^2left(b^2+c^2-a^2right)A+b^2left(c^2+a^2-b^2right)B+c^2left(a^2+b^2-c^2right)Ca^2left(b^2+c^2-a^2right)+b^2left(c^2+a^2-b^2right)+c^2left(a^2+b^2-c^2right).

Here U is the vector of the circumcenter and A, B, C are the vertex vectors. The divisor here equals 16S 2 where S is the area of the triangle.

Cartesian coordinates from cross- and dot-products

In Euclidean space, there is a unique circle passing through any given three non-collinear points P1, P2, and P3. Using Cartesian coordinates to represent these points as spatial vectors, it is possible to use the dot product and cross product to calculate the radius and center of the circle. Let

- P1=[x1y1z1],P2=[x2y2z2],P3=[x3y3z3]displaystyle mathrm P_1 =beginbmatrixx_1\y_1\z_1endbmatrix,mathrm P_2 =beginbmatrixx_2\y_2\z_2endbmatrix,mathrm P_3 =beginbmatrixx_3\y_3\z_3endbmatrix

Then the radius of the circle is given by

- r=|P1−P2||P2−P3||P3−P1|2|(P1−P2)×(P2−P3)|displaystyle mathrm r =frac P_1-P_2rightleft(P_1-P_2right)times left(P_2-P_3right)right

The center of the circle is given by the linear combination

- Pc=αP1+βP2+γP3displaystyle mathrm P_c =alpha ,P_1+beta ,P_2+gamma ,P_3

where

- α=|P2−P3|2(P1−P2)⋅(P1−P3)2|(P1−P2)×(P2−P3)|2β=|P1−P3|2(P2−P1)⋅(P2−P3)2|(P1−P2)×(P2−P3)|2γ=|P1−P2|2(P3−P1)⋅(P3−P2)2|(P1−P2)×(P2−P3)|2displaystyle beginalignedalpha =frac ^2left(P_1-P_2right)cdot left(P_1-P_3right)2left\beta =frac P_1-P_3right2left\gamma =frac ^2left(P_3-P_1right)cdot left(P_3-P_2right)2leftendaligned

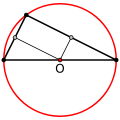

Location relative to the triangle

The circumcenter's position depends on the type of triangle:

If and only if a triangle is acute (all angles smaller than a right angle), the circumcenter lies inside the triangle.- If and only if it is obtuse (has one angle bigger than a right angle), the circumcenter lies outside the triangle.

- If and only if it is a right triangle, the circumcenter lies at the center of the hypotenuse. This is one form of Thales' theorem.

The circumcenter of an acute triangle is inside the triangle

The circumcenter of a right triangle is at the center of the hypotenuse

The circumcenter of an obtuse triangle is outside the triangle

These locational features can be seen by considering the trilinear or barycentric coordinates given above for the circumcenter: all three coordinates are positive for any interior point, at least one coordinate is negative for any exterior point, and one coordinate is zero and two are positive for a non-vertex point on a side of the triangle.

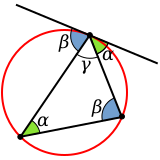

Angles

| |  |

The angles which the circumscribed circle forms with the sides of the triangle coincide with angles at which sides meet each other. The side opposite angle α meets the circle twice: once at each end; in each case at angle α (similarly for the other two angles). This is due to the alternate segment theorem, which states that the angle between the tangent and chord equals the angle in the alternate segment.

Triangle centers on the circumcircle of triangle ABC

In this section, the vertex angles are labeled A, B, C and all coordinates are trilinear coordinates:

Steiner point = bc / (b2 − c2) : ca / (c2 − a2) : ab / (a2 − b2) = the nonvertex point of intersection of the circumcircle with the Steiner ellipse. (The Steiner ellipse, with center = centroid(ABC), is the ellipse of least area that passes through A, B, and C. An equation for this ellipse is 1/(ax) + 1/(by) + 1/(cz) = 0.)

Tarry point = sec (A + ω) : sec (B + ω) : sec (C + ω) = antipode of the Steiner point- Focus of the Kiepert parabola = csc (B − C) : csc (C − A) : csc (A − B).

Other properties

The diameter of the circumcircle, called the circumdiameter and equal to twice the circumradius, can be computed as the length of any side of the triangle divided by the sine of the opposite angle:

- diameter=asinA=bsinB=csinC.displaystyle textdiameter=frac asin A=frac bsin B=frac csin C.

As a consequence of the law of sines, it does not matter which side and opposite angle are taken: the result will be the same.

The diameter of the circumcircle can also be expressed as

- diameter=abc2⋅area=|AB||BC||CA|2|ΔABC|=abc2s(s−a)(s−b)(s−c)=2abc(a+b+c)(−a+b+c)(a−b+c)(a+b−c)displaystyle beginalignedtextdiameter&=frac abc2cdot textarea=frac \&=frac abc2sqrt s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)\&=frac 2abcsqrt (a+b+c)(-a+b+c)(a-b+c)(a+b-c)endaligned

where a, b, c are the lengths of the sides of the triangle and s = (a + b + c)/2 is the semiperimeter. The expression s(s−a)(s−b)(s−c)displaystyle sqrt scriptstyle s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)

- diameter=2⋅areasinAsinBsinC.displaystyle textdiameter=sqrt frac 2cdot textareasin Asin Bsin C.

The triangle's nine-point circle has half the diameter of the circumcircle.

In any given triangle, the circumcenter is always collinear with the centroid and orthocenter. The line that passes through all of them is known as the Euler line.

The isogonal conjugate of the circumcenter is the orthocenter.

The useful minimum bounding circle of three points is defined either by the circumcircle (where three points are on the minimum bounding circle) or by the two points of the longest side of the triangle (where the two points define a diameter of the circle). It is common to confuse the minimum bounding circle with the circumcircle.

The circumcircle of three collinear points is the line on which the three points lie, often referred to as a circle of infinite radius. Nearly collinear points often lead to numerical instability in computation of the circumcircle.

Circumcircles of triangles have an intimate relationship with the Delaunay triangulation of a set of points.

By Euler's theorem in geometry, the distance between the circumcenter O and the incenter I is

- OI=R(R−2r),displaystyle OI=sqrt R(R-2r),

where r is the incircle radius and R is the circumcircle radius; hence the circumradius is at least twice the inradius (Euler's triangle inequality), with equality only in the equilateral case.[5][6]:p. 198

The distance between O and the orthocenter H is[7][8]:p. 449

- OH=R2−8R2cosAcosBcosC=9R2−(a2+b2+c2).displaystyle OH=sqrt R^2-8R^2cos Acos Bcos C=sqrt 9R^2-(a^2+b^2+c^2).

For centroid G and nine-point center N we have

- IG<IO,2IN<IO,OI2=2R⋅IN.displaystyle beginalignedIG&<IO,\2IN&<IO,\OI^2&=2Rcdot IN.endaligned

The product of the incircle radius and the circumcircle radius of a triangle with sides a, b, and c is[9]: p. 189, #298(d)

- rR=abc2(a+b+c).displaystyle rR=frac abc2(a+b+c).

With circumradius R, sides a, b, c, and medians ma, mb, and mc, we have[10]:p.289–290

- 33R≥a+b+c9R2≥a2+b2+c2274R2≥ma2+mb2+mc2.displaystyle beginaligned3sqrt 3R&geq a+b+c\9R^2&geq a^2+b^2+c^2\frac 274R^2&geq m_a^2+m_b^2+m_c^2.endaligned

If median m, altitude h, and internal bisector t all emanate from the same vertex of a triangle with circumradius R, then[11]:p.122,#96

- 4R2h2(t2−h2)=t4(m2−h2).displaystyle 4R^2h^2(t^2-h^2)=t^4(m^2-h^2).

Carnot's theorem states that the sum of the distances from the circumcenter to the three sides equals the sum of the circumradius and the inradius.[11]:p.83 Here a segment's length is considered to be negative if and only if the segment lies entirely outside the triangle.

If a triangle has two particular circles as its circumcircle and incircle, there exist an infinite number of other triangles with the same circumcircle and incircle, with any point on the circumcircle as a vertex. (This is the n=3 case of Poncelet's porism). A necessary and sufficient condition for such triangles to exist is the above equality OI=R(R−2r).displaystyle OI=sqrt R(R-2r).

Cyclic quadrilaterals

Cyclic quadrilaterals

Quadrilaterals that can be circumscribed have particular properties including the fact that opposite angles are supplementary angles (adding up to 180° or π radians).

Cyclic n-gons

For a cyclic polygon with an odd number of sides, all angles are equal if and only if the polygon is regular. A cyclic polygon with an even number of sides has all angles equal if and only if the alternate sides are equal (that is, sides 1, 3, 5, ... are equal, and sides 2, 4, 6, ... are equal).[12]

A cyclic pentagon with rational sides and area is known as a Robbins pentagon; in all known cases, its diagonals also have rational lengths.[13]

In any cyclic n-gon with even n, the sum of one set of alternate angles (the first, third, fifth, etc.) equals the sum of the other set of alternate angles. This can be proven by induction from the n=4 case, in each case replacing a side with three more sides and noting that these three new sides together with the old side form a quadrilateral which itself has this property; the alternate angles of the latter quadrilateral represent the additions to the alternate angle sums of the previous n-gon.

Let one n-gon be inscribed in a circle, and let another n-gon be tangential to that circle at the vertices of the first n-gon. Then from any point P on the circle, the product of the perpendicular distances from P to the sides of the first n-gon equals the product of the perpendicular distances from P to the sides of the second n-gon.[9]:p. 72

Point on the circumcircle

Let a cyclic n-gon have vertices A1 , ..., An on the unit circle. Then for any point M on the minor arc A1An, the distances from M to the vertices satisfy[14]:p.190,#332.10

- {MA1+MA3+⋯+MAn−2+MAn<n/2if n is odd;MA1+MA3+⋯+MAn−3+MAn−1≤n/2if n is even.displaystyle begincasesMA_1+MA_3+cdots +MA_n-2+MA_n<n/sqrt 2&textif ntext is odd;\MA_1+MA_3+cdots +MA_n-3+MA_n-1leq n/sqrt 2&textif ntext is even.endcases

Polygon circumscribing constant

A sequence of circumscribed polygons and circles.

Any regular polygon is cyclic. Consider a unit circle, then circumscribe a regular triangle such that each side touches the circle. Circumscribe a circle, then circumscribe a square. Again circumscribe a circle, then circumscribe a regular 5-gon, and so on. The radii of the circumscribed circles converge to the so-called polygon circumscribing constant

- ∏n≥31cos(πn)=8.7000366….displaystyle prod _ngeq 3frac 1cos left(frac pi nright)=8.7000366ldots .

(sequence A051762 in the OEIS). The reciprocal of this constant is the Kepler–Bouwkamp constant.

See also

- Circumgon

- Circumscribed sphere

- Inscribed circle

- Japanese theorem for cyclic polygons

- Japanese theorem for cyclic quadrilaterals

Jung's theorem, an inequality relating the diameter of a point set to the radius of its minimum bounding sphere- Kosnita theorem

- Lester's theorem

- Tangential polygon

- Triangle center

Notes

^ ab Whitworth, William Allen. Trilinear Coordinates and Other Methods of Modern Analytical Geometry of Two Dimensions, Forgotten Books, 2012 (orig. Deighton, Bell, and Co., 1866). http://www.forgottenbooks.com/search?q=Trilinear+coordinates&t=books

^ ab Clark Kimberling's Encyclopedia of Triangles "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2012-06-02.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link).mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Wolfram page on barycentric coordinates

^ Dörrie, Heinrich, 100 Great Problems of Elementary Mathematics, Dover, 1965.

^ Nelson, Roger, "Euler's triangle inequality via proof without words," Mathematics Magazine 81(1), February 2008, 58-61.

^ Dragutin Svrtan and Darko Veljan, "Non-Euclidean versions of some classical triangle inequalities", Forum Geometricorum 12 (2012), 197–209. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2012volume12/FG201217index.html

^ Marie-Nicole Gras, "Distances between the circumcenter of the extouch triangle and the classical centers",

Forum Geometricorum 14 (2014), 51-61. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2014volume14/FG201405index.html

^ Smith, Geoff, and Leversha, Gerry, "Euler and triangle geometry", Mathematical Gazette 91, November 2007, 436–452.

^ abc Johnson, Roger A., Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover, 2007 (orig. 1929).

^ Posamentier, Alfred S., and Lehmann, Ingmar. The Secrets of Triangles, Prometheus Books, 2012.

^ ab Altshiller-Court, Nathan, College Geometry, Dover, 2007.

^ De Villiers, Michael. "Equiangular cyclic and equilateral circumscribed polygons," Mathematical Gazette 95, March 2011, 102–107.

^

Buchholz, Ralph H.; MacDougall, James A. (2008), "Cyclic polygons with rational sides and area", Journal of Number Theory, 128 (1): 17–48, doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2007.05.005, MR 2382768.

^ Inequalities proposed in “Crux Mathematicorum”, [1].

References

Coxeter, H.S.M. (1969). "Chapter 1". Introduction to geometry. Wiley. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-471-50458-0.

Megiddo, N. (1983). "Linear-time algorithms for linear programming in R3 and related problems". SIAM Journal on Computing. 12 (4): 759–776. doi:10.1137/0212052.

Kimberling, Clark (1998). "Triangle centers and central triangles". Congressus Numerantium. 129: i–xxv, 1–295.

Pedoe, Dan (1988) [1970]. Geometry: a comprehensive course. Dover. ISBN 0-486-65812-0.

External links

Derivation of formula for radius of circumcircle of triangle at Mathalino.com

Semi-regular angle-gons and side-gons: respective generalizations of rectangles and rhombi at Dynamic Geometry Sketches, interactive dynamic geometry sketch.

MathWorld

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Circumcircle". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Cyclic Polygon". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Steiner circumellipse". MathWorld.

Interactive

Triangle circumcircle and circumcenter With interactive animation- An interactive Java applet for the circumcenter

![displaystyle beginalignedS_x&=frac 12det mathbf A ,\[5pt]S_y&=frac 12det mathbf B ,\[5pt]a&=det beginbmatrixA_x&A_y&1\B_x&B_y&1\C_x&C_y&1endbmatrix,\[5pt]b&=det ^2\B_x&B_y&endaligned](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1649c42b7532a101a98ee8d0eb5f18f72a4922a1)

![displaystyle mathrm R (s)=mathrm P_c +cos left(frac mathrm s mathrm r right)(P_0-P_c)+sin left(frac mathrm s mathrm r right)left[widehat ntimes (P_0-P_c)right].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7a70aa6cf6f613352caa88916c82a86f03bbc8b4)

![displaystyle beginalignedU_x&=frac 1Dleft[left(A_x^2+A_y^2right)left(B_y-C_yright)+left(B_x^2+B_y^2right)left(C_y-A_yright)+left(C_x^2+C_y^2right)left(A_y-B_yright)right]\U_y&=frac 1Dleft[left(A_x^2+A_y^2right)left(C_x-B_xright)+left(B_x^2+B_y^2right)left(A_x-C_xright)+left(C_x^2+C_y^2right)left(B_x-A_xright)right]endaligned](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f18b164631a503473d381715265669aaebd2f509)

![displaystyle D=2left[A_xleft(B_y-C_yright)+B_xleft(C_y-A_yright)+C_xleft(A_y-B_yright)right].,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6dfe50a8ec47588a885cce5ed93f76012335087f)

![displaystyle beginalignedU'_x&=frac 1D'left[C'_yleft(B'_x^2+B'_y^2right)-B'_yleft(C'_x^2+C'_y^2right)right],\U'_y&=frac 1D'left[B'_xleft(C'_x^2+C'_y^2right)-C'_xleft(B'_x^2+B'_y^2right)right]endaligned](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fb52f9069c5391ba4003bc27e8d6d3bacbd7a008)