Kingdom of Ait Abbas

Kingdom of Beni Abbas ⵜⴰⴳⴻⵍⴷⴰ ⵏ ⴰⵜ ⵄⴻⴱⴱⴰⵙ, Tagelda n Ait Abbas سلطنة بني عباس, salṭanat Beni Ɛabbas | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1510–1872 | |||||||||||

Flag | |||||||||||

Kingdom of Ait Abbas at its greatest extent in the end of the 16th century. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Kalâa of Ait Abbas | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Berber, Arabic | ||||||||||

| Religion | • Islam • Minorities: Christianity and Judaism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||

• 1510–1559 | Abdelaziz Labes | ||||||||||

• 1871-1872 | Boumezrag El Mokrani | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||||

• Established | 1510 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1872 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Algeria |

|

Prehistory

|

Antiquity

|

Middle Ages

|

Modern times Ottoman Algeria (16th - 19th centuries)

French Algeria (19th - 20th centuries)

|

Contemporary era 1960s–80s

1990s

2000s to present

|

Related topics

|

The kingdom of the Ait Abbas or sultanate of the Beni Abbas, in (Berber (phonetic) tagelda n At Ɛebbas, ⵜⴰⴳⴻⵍⴷⴰ ⵏ ⴰⵜ ⵄⴻⴱⴱⴰⵙ; Arabic: salṭanat Beni Ɛabbas, سلطنة بني عباس), is a former berber state of North Africa, then a fief and a principality, controlling Lesser Kabylie and its surroundings from the sixteenth century to the nineteenth century. It is referred to in the Spanish historiography as "reino de Labes";[1] sometimes more commonly referred to by its ruling family, the Mokrani, in Berber At Muqran, in Arabic أولاد مقران (Ouled Moqrane). Its capital was the Kalâa of Ait Abbas, an impregnable citadel in the Biban mountain range.

Founded by last Hafsid dynasty emirs of Bejaia, the kingdom was for a long time a bastion of resistance to the Spaniards, then to the regency of Algiers. Strategically located on the road from Algiers to Constantine and from the Mediterranean Sea to the Sahara, its capital Kalâa of Ait Abbas attracted Andalusians, Christians and Jews in the sixteenth century, fleeing Spain or Algiers. Their know-how enriched a local industrial fabric whose legacy is the handicraft of the Ait Abbas tribe. The surrounding tribes were also home to intense intellectual activity and a literary tradition that rivalled those of other Maghreb cities.

At its peak, the influence of the kingdom of Ait Abbas extended from the valley of the Soummam to the Sahara and its capital the Kalâa rivalled the biggest cities. In the seventeenth century, its chiefs took the title of sheikh of the Medjana, but were still described as sultans or kings of the Beni Abbés.[1] At the end of the eighteenth century, the kingdom led by the Mokrani family (Amokrane) broke up into several clans, some of which became vassals of the regency of Algiers. However, the Sheikh of the Medjana maintained himself at the head of his principality as a tributary of the Bey of Constantine, managing his affairs independently.

With the arrival of the French, some Mokrani took the side of the colonisers, while others sided with the resistance. The French, to strengthen their hold in the region, relied on the local lords, maintaining an appearance of autonomy of the region under its traditional leaders until 1871. Its sovereigns assumed various titles, successively sultan, amokrane [2] and sheikh of the Medjana. Temporarily integrated into the French military administration before the revolt of 1871, they were known as khalifa and bachagha. The defeat of 1871 marked the end of the political role of the Mokrani with the surrender of the Kalâa to the French.

Contents

1 History 1510-1830

1.1 The Maghreb political space in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries

1.2 Foundation at the beginning of the sixteenth century

1.3 Alliance with Algiers

1.4 War with Algiers

1.5 The kingdom at its peak

1.6 17th and 18th centuries

1.7 Dissent and relations with the Beylik of Constantine

2 The fall of the Mokranis, 1830-1872

2.1 After the fall of Algiers

2.2 The period of the khalifas

2.3 the collapse of Mokrani authority

3 Relations with neighbours

3.1 Spain

3.2 Kingdom of Kuku

3.3 Regency of Algiers

3.4 The Sahara

4 Social basis of power

5 Written culture

6 Architecture

7 Economy

7.1 Natural resources and agriculture

7.2 Commerce

7.3 Arts and crafts

8 See also

9 Bibliography

10 Old secondary sources

11 Primary sources

12 Contemporay sources

13 Notes

14 References

History 1510-1830

The Maghreb political space in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries

Hafside coin of Bejaia (1249-1276).

Ifriqiya, which corresponds to the eastern part of the present-day Maghreb, was part of the Hafsid kingdom. In this kingdom, the city of Bejaia, the ancient capital of the Hammadids in the eleventh century, was a prominent city. Indeed, its wealth and its strategic port location made it an object of covetousness for the Zayyanids and the Marinids; moreover, it often dissented within the Hafsid sultanate, and enjoyed a certain autonomy in normal times. The city was seen as the capital of the western regions of the Hafsid sultanate and it's "frontier place". In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries it became, on various occasions, the seat of power of independent emirates-governors[3] or dissidents from the Hafsid dynasty. These "sovereigns of Béjaïa"[4] extended their authority - which often went hand in hand with political dissent - to the entire domain of the ancient kingdom of the Hammadids: Algiers, Dellys, Medea, Miliana, Constantine, Annaba and the oases of the Zab. Ibn Khaldun describes them as ruling "Biğāya wa al-ṯagr al-garbī min Ifriqiya" (the city of Bejaia and the western march of Ifrīqiya). Ibn Khaldoun was also the vizier of the independent administration of a Hafsid prince of Béjaïa in 1365.[5] The fifteenth century saw a general return to the centralization of the Hafsid state. But at the end of the fifteenth century and the beginning of the sixteenth, Leo the African and Al-Marini described a prince of Bejaia, distinct from Tunis, in a position similar to Constantine and Annaba, reflecting a fragmentation of Hafsid territory.[6] These last emirs of Bejaia, independent of the central power of Tunis, were the origin of the dynasty that was to found and direct the kingdom of Beni Abbes.

Foundation at the beginning of the sixteenth century

Map of the kingdom of Kuku and the kingdom Ait Abbas (Labes) according to the Spanish map of the sixteenth century, preserved in the archives of Simancas.

In 1510, as part of the Reconquista, the Spaniards seized Bejaia, which was in the hands of dissident Hafsid emirs. They organized raids in the hinterland from this position. The Berbers of the region sought protection in the interior and took as their new capital the Kalâa of the Beni Abbas, in the heart of the Bibans mountains. This city was an ancient fortified place of the Hammadid era and a staging point on the triq sultan the commercial route going from Hautes Plaines to Béjaia. Abderahmane, the last of the emirs of Bejaia, chose the site for security reasons. His son Ahmed became famous for his religious status with the Kabylian and Arab tribes in the region who settled in the Kalâa, fleeing the relative chaos in the country. Benefiting from growing support among the surrounding tribes, he proclaimed himself "Sultan of the Kalâa". He was buried in Takorabt, a village in the vicinity of the Kalâa.[7][8]

Map of Béjaia in the 16th century.

The reign of his grandson Abdelaziz El Abbes brought the name of the Kalâa to wider attention: at its peak, the city had 80,000 inhabitants.[9] The Kalâa was equipped with weapons factories with the help of Christian renegades as well as some of the inhabitants of Bejaia driven out by the Spanish occupation, including Andalusians, Muslims, as well as a Jewish community who were welcomed for their know-how.[10]

Alliance with Algiers

Following successive annexations of territory, the kingdom of Ait Abbas Under Abdelaziz extended to the south and the surrounding mountains. The Spaniards, who had fallen back into Bejaia, offered him their alliance, and he temporarily ignored the establishment of the regency of Algiers led by the Barbarossa brothers because his kingdom was not oriented towards the sea. The Barbarossa brothers, wishing to isolate the Spaniards, attacked Abdelaziz and met him around Bejaïa in 1516. Faced with the technical superiority of their firearms, Abdelaziz submitted to them and preferred to break the alliance with the Spaniards, rather than confront the Turks immediately with inadequate resources.[11] In 1542, the regency of Algiers made the lord of the Kalâa, his khalifa (representative) in the Medjana.[12]

Abdelaziz used his reign and periods of peace with the Regency to fortify the Kalâa and to extend his influence further to the south. His infantry became a regular corps of 10,000 men, and he bought two regular cavalry corps. He built two borjs around the Kalâa, each with a khalifa (representative), who was in charge of making tours through his territory.[13]

This increasing power of the Sultan of the Kalâa worried the Turks of the regency of Algiers who, in 1550, twice sent troops that Abdelaziz repulsed. Hassan Pasha therefore concluded a treaty with him and obtained his aid in his expedition against Tlemcen (1551), then occupied by Sherif Saadi. According to the Spanish contemporary writer Luis del Mármol Carvajal, Abdelaziz commanded an infantry corps of 6,000 men for the Tlemcen expedition. According to historian Hugh Roberts, the Kabyle contingent amounted to 2,000 men.[14][15]

Elements of Andalusian architecture of the Mausoleum of Sultan Ahmed.

The arrival of Salah Rais at the head of the regency of Algiers confirmed the alliance with Abdelaziz, and they jointly led the Touggourt Expedition (1552). Abdelaziz sent 180 arquebusiers and 1,600 horsemen, in addition to the 3,000 arquebusiers of Salah Raïs. The Berbers of Abdelaziz dragged way guns, hoping to learn how to maneuver them and know how to hoist them up to their fortress of the Kalâa.

War with Algiers

Two hypotheses explain the eventual rupture with Algiers, according to Spanish historiography. The first is that Salah Rais tried to arrest Abdelaziz during his time in Algiers, suspecting him of wanting to raise the country against the regency of Algiers. The second is that Abdelaziz was suspicious of the Turks and their ability to attack distant cities like Touggourt. He feared that their ambition to control the country would end up making his kingdom a target and considered it a political mistake to have favored them through the two expeditions. The narratives of the Aït Abbas report that the rupture was linked to an attempt by the regency of Algiers to have Abdelaziz assassinated by Zouaouas auxiliaries. They refused to murder a chief of the same region and warned him instead. Allied with the Zouaoua, the troop of Sultan Abdelaziz defeated the Janissaries who had to retreat to Algiers.[16]

Salah Rais, for fear that the reputation of Sultan Abdelaziz would increase, launched an expedition in late 1552 and reached the Boni Mountains near the Kalâa by winter. Abdelaziz's brother, Sidi Fadel, died in battle but the snow prevented the Turks from advancing further and exploiting their victory.[17][18]

In 1553, the son of Salah Rais, Mohamed-bey, led an offensive on the Kalâa of the Beni Abbes which resulted in defeat and many losses among the Turks. Their reputation was tarnished by this battle because they avoided a disaster thanks to the support of the Arab tribes. Abdelaziz also repelled an expedition commanded by Sinan Reis and Ramdan Pasha near Wadi el Hammam, towards M'sila. The capture of Bejaia by Salah Rais in 1555 confirmed Abdelaziz's fears about the power of the regency of Algiers and he continued to strengthen his positions in the mountains. However, Salah Rai died and the return of Hassan Pasha allowed a return to peace for a year. Hassan Pasha delivered the town of M'sila and its defenses including 3 pieces of artillery to Abdelaziz, while maintaining control over tax contributions.[19][20][21]

The troops of the regency of Algiers allied to the kingdom of Beni Abbes marching towards Tlemcen.

Abdelaziz was therefore in possession of the city of M'sila and raised an army of 6,000 men among the surrounding tribes in order to levy the tax normally intended for the Turks of the Regency. Hassan Pasha declared war on him in 1559, took M'sila without difficulty and fortified Bordj of Medjana and the Bordj Zemoura. These two forts and their garrisons were immediately destroyed by a counter-attack by Abdelaziz who also took the artillery pieces to improve the defense of the Kalâa. Hassan Pasha, married to the daughter of the King of Kuku, formed an alliance with the latter to put an end to the sultan of Kalâa. He brought him to battle in front of the Kalâa in 1559, without being able to take it and suffering many losses. However, his rival Sultan Abdelaziz died on the second day of the fighting and his brother Sultan Ahmed Amokrane, his chosen successor, drove back the Turkish and Kuku forces. This decisive victory of the Kalâa made Hasan abandon his ambitions for a time; he consoled himself by who carrying the head of Abdelaziz to Algiers as a trophy.[22][23][19]

The kingdom at its peak

Conquests of Ahmed Amokrane, late 16th century

In 1559, sultan Ahmed Amokrane organised his army and welcomed renegades from Algiers as well as Christians, authorised to follow their faith. With these revived forces of 8000 infantry and 3000 horses he launched a campaign in the south. He subjugated Tolga and Biskra, and reached Touggourt where he named a member of a loyal tribe, the Hachem, El Hadj Khichan el Merbaï, as Sheikh. One of his close relatives was made Sheikh of the Tolga and Biskra oases, and Abd el-Kader Ben Dia, made khalifa in the Sahara, devoted great energy to defending his Sultan's interests in the region. Ahmed Mokrane established a network of signalling posts on high peaks, which sent messages by fire at night and by smoke during the day to relay messages from the southern domains to the Kalâa.[24]

Ahmed Amokrane then turned his attention to the territory of the Ouled Naïl, which he took from Bou Saâda to Djelfa. The date of these expeditions is generally held to be around 1573.[25] This period marks the high point of the kingdom in terms of its governance and the administration of its territories. Ahmed Amokrane was bold enough to send his own son to Algiers in 1580 to welcome the newly arrived Jaafar Pasha.[26] By 1590, his influence was such that whole tribes paid tribute to him rather than to Algiers. Khizr Pacha went back to war with him and laid siege to the Kalâa for two months, but he was unable to take it. Instead, he pillaged the surrounding countryside, razing its villages. Hostilities were eventually ended following mediation by a marabout, which involved Ahmed Amokrane paying a tribute of 30000 douros to secure Khizr Pasha's withdrawal and recognition of his independence.[27]

In 1598, it was Ahmed Amokrane who laid siege to Algiers: with the help of the townspeople, he managed to force the gate at Bab Azoun and breaking into the city, though he could not maintain his hold there. The siege lasted eleven days.[28]

17th and 18th centuries

Family tree of the Amokrane (or Mokrani) according to Louis Rinn (c.1891)

In 1600, Ahmed Amokrane marched against the forces of Soliman Veneziano, Pasha of Algiers, which were trying to enter Kabylie. He defeated them and destroyed Borj Hamza, built in 1595 at Bouira, but he died during the fighting. He left as his legacy the family name "Amokrane" (meaning 'great' or 'leader" in kabyle) which was later arabised as "Mokrani", to hs descendents.[29][30]

His successor was Sidi Naceur Mokrani, who was very religious and surrounded himself with scholars and students of Islam, neglecting the affairs of his kingdom. This provoked the anger of his military commanders and of the merchants of Aït Abbas. Sidi Naceur was ambushed and assassinated in 1620. His children survived however, and his oldest son, Betka Mokrani, was taken in by the Hashemite tribe and raised among them. They helped him regain his princely rank by marrying him to the daughter of the chief of the Ouled Madi.[31]

Si Betka took part in the battle of Guidjel on 20 September 1638), at which the tribes fought together with the armies of Constantine against the Pasha of Algiers. This led to the Beys of Constantine becoming effectively independent of Ottoman rule from Algiers. Si Betka Mokrani simply never recognised the authority of Algiers, and managed to reconquer the lands of his grandfather. However instead of styling himself "Sultan of the Kalâa" he assumed the title "Sheikh of the Medjana'". He defeated the Aït Abbas tribe several times, but refused to return to his ancestral seat at the Kalaa. He died in 1680 at his fortress of "Borj Medjana", leaving four sons - Bouzid, Abdallah, Aziz and Mohammed-el-Gandouz.[27][32]

The oldest son, Bouzid Mokrani, known as sultan Bouzid,[note 1] who ruled from 1680 to 1735 on the same terms as his father, entirely free from the authority of Algiers. After a period of dissent from hs brothers, he managed to maintain family stability. He twice fought against the Regency of Algiers, which wanted him to allow its armies to cross his territory in order to link Algiers with Constantine, particularly through the strategic pass known as "the iron gates" in the Biban mountains. Having defeated Algiers, he reinstituted the "ouadia", a system which required Algiers to pay him if it wished to move its troops across his land. This arrangement remained in place until the fall of the Regency of Algiers in 1830.[33] The origins of the ouadia lay in the victory of the Aït Abbas over the Turks in 1553 and 1554, which had effectively made the Mokranis lords of the Hodna and the Bibans.[34]

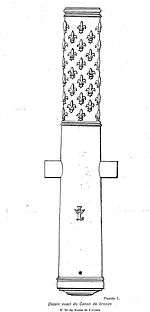

Sketch of a cannon from the time of Louis XIV, probably from the Djidjelli Expedition (1664), found at the Kalâa of Ait Abbas[35]

Despite this arrangement, the Mokranis refused to allow passage Algerian troops to cross their land when the French attacked the coast in 1664 during the Djidjelli Expedition. Ali, king of Kuku likewise refused passage to the armies of Algiers.[36] Nevertheless, they did join a jihad with Algiers and Constantine to repel the duke of Beaufort, Louis XIV's commander.[37]

The Berbers sought to negotiate with the duke of Beaufort, who was dug in around Djidjelli, Be he rejected their peace proposals.[38] The expedition ended with victory for the Berbers and Turks and a major defeat for Louis XIV, whose armies abandoned their artillery.[39] The Mokranis took the cannon away to the Kalaa as trophies, with their fleur de lys decorations.[40] Other French-type cannons were also found at the Kalaa later, most probably these date from the time of Louis XII, and were presented by Francis I of France to Tunis as part of his alliance with the Ottoman Empire. They were then captured by emperor a Charles V when he took Tunis in 1535, and transported to Béjaïa, which was a Spanish possession until 1555. From there, it appears that they were passed on to the Aït Abbas when they were Spanish allies.[41] A smaller cannon, also found in the Kalaa, indicates that there was a local foundry for small-bore guns, operated by a Spanish renegade.[42]

Dissent and relations with the Beylik of Constantine

After the death of Bouzid Mokrani in 1734, his son El hadj Bouzid Mokrani to power after his older brother Aderrebou Mokrani renounced the succession. He was opposed by two other brothers, Bourenane et Abdesselam Mokrani and by his cousin Aziz ben Gandouz Mokrani, son of Mohammed-el-Gandouz. Aziz created a "soff" (faction) of dissidents who aligned themselves with the Turks, who were known as the Ouled Gandouz.[43][44]

The Turks in Algiers wanted revenge for a massacre in 1737, when an entire column of their troops and its commander had been slaughtered by the "Sheikh of the Medjana" in retaliation for a crime of honour. Allied with the Ouled Gandouz and exploiting divisions between Bourenane et Abdesselam Mokrani, they inflicted defeat on them in 1740. The Aït Abbas had to abandon the Medjana and take refuge in the mountains, with El hadj Bouzid sheltering at the Kalaa. This was the second period of domination by Algiers after the first in 1559. The Turks rebuilt the fort of Bordj Bou Arreridj, and left a garrison of 300 janissaries there. They also installed their ally Aziz ben Gandouz Mokrani as caïd, at the head of the Ouled Madi tribe.[43][45]

The feuding Mokrani brothers were eventually reconciled by a leader of the Shadhili order so that they could form a united front against the Turks. They defeated them, demolished the fort at Bordj Bou Arreridj and sent the surviving janissaries back to Algiers with a letter affirming Mokrani independence. El hadj Bouzid Mokrani resumed authority over the Medjana and the Regency of Algiers recognised his independence, renouncing their claim that the tribes under Mokrani control needed to pay taxes to Algiers. Each year, the "Sheikh of the Medjana" was to receive a kaftan of honour from Algiers together with gifts recognising his independence. This diplomatic solution allied the Turks to find pretexts for intervening in Mokrani affairs or demanding support for a faction favourable to them.[46] The territory of El Hadj Bouzid was a state-within-a-state of the Ottoman domains.[47]

Before his death in 1783, El hadj Bouzid Mokrani married his daughter Daïkra to the Bey of Constantine, Ahmed el Kolli. He was succeeded by his brother, Abdessalam Mokrani, while his eldest son became heir apparent. The Ouled Bourenane and Ouled Gandouz rebelled however, and this provided a pretext for the Bey to involve himself in a Mokrani affairs. Without intervening militarily, he succeeded in getting all the Mokrani clans to weaken each other, recognising as Sheikh whichever of them was able to send him tribute.[46]

By this means the Mokrani became vassals of the Bey of Constantine, though with unusual arrangements. Rather than paying tribute to him, they received it in the form of the "ouadia", which gave him the right to march his troops over their land. He recognised the right of the Sheikh of the Medjana to administer justice, and it was agreed that the fort at Bordj Bou Arreridj was not to be rebuilt. In 1803 the Mokranis faced a peasant revolt from the Ouled Derradj, Madid, Ayad, Ouled Khelouf, Ouled-Brahim and Ouled Teben, led by sheikh Ben el Harche.[48] Ben el Harche, a religious leader, defeated the army of Osman Bey, who died in battle.[49] He based himself in the Djebel Megris, but died fighting in 1806 after two battles against the Mokranis, supported by a column of a Turkish troops from the Bey.[48]

After numerous fratricidal struggles, by 1825 there were no more than two Mokrani factions with any real power: the Ouled el Hadj and the Ouled Abdesselem. These two groups were led by Ben Abdallah Mokrani, who held the title "Sheikh of the Medjana". The appointment of Ahmed Bey as Bey of Constantine, who was himself a relative of the Mokrani, led to further clan disputes, and Ahmed Bey was able to eliminate a number of Mokrani before being defeated by those who remained, from the dissident groups of Ouled Bourenane and Ouled Gandouz.[50]

Ben Abdallah Mokrani had two lieutenants, Ahmed Mokrani and his cousin Abdesselem Mokrani. He entrusted the latter with collecting taxes for him in the Bibans. This lucrative task was coveted by Ahmed Mokrani, making it the starting point of a rivalry which lasted until the arrival of the French. The two lieutenants joined the forces of Ahmed Bey which went to the assistance of the Dey of Algiers in 1830.[51]

The fall of the Mokranis, 1830-1872

After the fall of Algiers

News of the fall of Hussein Dey spread rapidly across the country, carried by defeated tribesmen returning to their homelands. As the Turkish elite enjoyed no public sympathy, a series of uprisings threatened the foundations of Algerian society. This period of turbulence saw the strengthening of traditional tribal confederations and social arrangements which the Regency of Algiers had worked to diminish. Aside from the tribal confederations in the mountainous regions, it was the traditional marabout elements and the hereditary leadership, known as the "djouad" - which included the Mokrani - who took the lead in reasserting their positions.[48]

In the west of the country it was the marabouts who predominated, leading to the emergence of Emir Abdelkader. In the east, the "djouad" were more firmly established, as was the Beylik of Constantine. The resilience of the beylik was largely due to the flexible policies of Ahmed Bey and his advisors, who relied on the leading feudal chieftains. Nevertheless, even here there was a tribal rebellion against him. This divided the Mokrani family, as Abdesselem Mokrani supported the rebels in the name of Ben Abdallah Mokrani, Sheikh of the Medjana. His cousin and rival Ahmed Mokrani however remained loyal to Ahmed Bey. He and other chiefs allied to the Bey, including sheikh Bengana, managed to win back or bribe various rebel tribes, so that their insurrection came to nothing.[52]

In 1831, Abdesselem Mokrani and has allies proposed that the French recognise their authority, in return for a military effort that they hoped would help them get rid of Ahmed Bey. The French would not entertain this proposal howeve. A similar letter sent to the Bey of Tunis Al-Husayn II ibn Mahmud was intercepted by Ahmed Bey. Abdesselem Mokrani was subsequently captured and imprisoned in Constantine.

Ahmed Mokrani was appointed sheikh of the Medjana by Ahmed Bey, in the place of Ben Abdallah Mokrani who soon died. Ahmed Mokrani took part in the defence of Constantine in 1836, and again when the city fell to the French in 1837. His rival Abdesselem Mokrani, took advantage of the chaos to escape from Constantine in 1837.[53]

The period of the khalifas

A group crossing the Iron Gates pass in 1839. To make use of this narrow route, the Regency of Algiers paid the "ouadia".

Ahmed Mokrani followed Ahmed Bey and fled to the south before returning to his territory and falling back on the Kalâa of Ait Abbas; his rival Abdesselem Mokrani meanwhile took possession of the Medjana plain. In December 1837, when the Emir Abdelkader arrived in the Biban mountains to organise the administration of a region he considered to be part of his realm, each of the rivals offered allegiance to him if he would agree to their respective terms. As Abdesselem Mokrani was in a better position, it was he whom Abdelkader recognised as "khalifa of the Medjana."[54] Ahmed Mokrani was unable to overthrow his cousin, who was supported by the Hachem, the Ouled Madi of Msila and the marabouts. Even the Aït Abbas tribe, until then favouring Ahmed Mokrani, saw unrest grow against him in Ighil Ali, Tazaert and Azrou. To avoid being cut off in the Kalaa, he had to take refuge with the neighbouring Beni Yadel tribe at El Main.[55] In the end he was captured by Abdesselem Mokrani who exiled him to the Hodna.

At the end of July 1838 Ahmed Mokrani escaped and presented himself to the French authorities in Constantine. Having been appointed caïd by them, he was also given, on 30 September, the title "khalifa of the Medjana" by the French, who had by now occupied Sétif.[56] The title "khalifa" was used only in territories where the French did not exercise direct rule and which enjoyed the same privileges as they had under the Beylik of Constantine. "Khalifas" received local taxes on behalf of the state, maintained a guard of spahis paid for by France and governed their people according to Islamic law. These allies were invaluable to the French as supporters of their rule in a country they barely yet knew.[57]

In 1838 Abdesselem Mokrani was dismissed by Emir Abdelkader and replaced by his "khodja" (secretary), a man of marabout rather than noble pedigree. This was considered an affront for a "djouad", but was accepted by Abdesselem Mokrani as a means of blocking the advances of his cousin Ahmed Mokrani who was extending his alliances and influence. Ahmed encouraged the French to conduct the Iron Gates expedition in October 1839, to take control of this strategic route through the Biban mountains.[58] Ahmed ensured that his vassals in the area allowed the French army to pass through unmolested. Using this route allowed the French to take more effective control of the area and to link Algiers with Constantine.[59] Abdesselem Mokrani was left with no real support, Ahmed Mokrani had rebuilt his domain with French assistance. Emir Abdelkader considered the Iron Gates to be part of his own territory, and therefore declared war on France and on the local chiefs who supported her. The resulting conflict had serious consequences for the Medjana, and Ahmed Mokrani, allied to the French, was forced to retreat into the Kalâa of Ait Abbas. The followers of Abdelkader were finally repulsed in 1841. After this Ahmed Mokrani ruled his territories with little regard for French authority, remaining however in contact with captain Dargent in the base at Sétif[60][61]

His standing as a French ally continued to change. A French Royal ordinance of 15 April 1845 superseded the decrees of 1838 and gave him the status of a high official. Some tribes of the Ouled Naïl, Aït Yaala, Qsar, Sebkra, Beni Mansour, Beni Mellikech and the Biban mountains were detached from his command and placed under the authority of more pliable nobles or caïds. In 1849, the tribes of the Hodna were similarly removed from his control.[62] It was against this background that one of the leading figures of kabylie resistance to the French emerged in the person of Chérif Boubaghla.[63] In 1851 he began moving through the Medjana plain, the Kalaa, and the lands of the Beni Mellikech who had still not submitted to the French. Though the intermediary of a man named Djersba Ben Bouda, who was intendant of the Kalaa, Boubaghla sent Ahmed Mokrani a letter proposing war against the French, but the "khalifa" did not take this proposal seriously. Instead, he provided support for the columns of French troops sent to defeat Boubaghla in 1854. He took advantage of this action to punish certain Aït Abbas villages which in the past had been loyal to his rival Abdesselem, by accusing them of supporting Boubaghla. He died in 1854 at Marseille while returning from a visit to France, and his son Mohamed Mokrani was named Bachagha.[64]

the collapse of Mokrani authority

Portrait of the bachagha Mohamed Mokrani.

The title "bachagha" (Turkish: başağa=chief commander) was a creation of the French authorities, denoting an intermediate status between "caid" and "khalifa". The "khalifas", still of major importance, was later suppressed. The French continued to appoint "caids" and commanders for the tribes previously assigned to Ahmed Mokrani.

In 1858, he was obliged to turn over some fines which he had collected in his own name to the French treasury. The zakat tax, already paid in kind to the Mokranis, was introduced in the Bordj Bou Arreridj region. The Hachem tribe was also obliged to pay the "achour" (tithe), and eventually the Mokrani themselves were brought under the cash payment system. In 1858 and 1859 they were granted an exemption however, ostensibly because of poor harvests, but in fact in order to accommodate them politically.[65]

Finally, the "oukil" or local agents of the Mokrani were replaced by caïds or sheikhs appointed directly by the colonial administration. 1859 and 1860 saw the suppression of the right of feudal lords to administer and the right to the "khedma", which tradiionally allowed the beneficiary to claim a fee in return for bearing letters or orders from the administration (formerly, on behalf of the Bey). These measures provoked discontent among the traditional chiefs allied to France, but they still sought to avoid armed conflict and hoped that the French would continue to bed them to administer the territory. The reassuring official statements from the French governmen5 and from Napoleon III about the role of the Algerian feudal nobility were unconvincing and unsupported by deeds. The transfer from military to civilian rule prompted Mohamed Mokrani to resign from his position as bachagha, and by 1870 he had begun to seriously consider rebellion.[66]

In parallel with the political situation, the years 1865 and 1866 were a social disaster for Algeria, where they were commonly referred to as "am ech cher" (the years of misery). A plague of locusts followed by a drought plunged the country into famine, followed by epidemics of cholera and typhus. The traditional leaders emptied their personal granaries to feed their people, and once these were exhausted, borrowed to keep them supplied.[67] These loans were later to place Mohamed Mokrani in difficulties.[68]

Map showing the geographic extent of the Mokrani revolt.

Engraving showing the siege of Bordj Bou Arreridj in 1871.

On 15 March 1871 Mohamed Mokrani joined the revolt of the spahis in eastern Algeria.[69] He sent 6000 men to attack Bordj Bou Arreridj, which he besieged and burned. On 8 April he was joined in revolt by the Rahmaniyya brotherhood under its leader Sheikh Aheddad. The whole of eastern Algeria now rose, from the outskirts of Algiers itself to Collo, with 150,000 Kabylies under arms at the height of the rebellion. However divisions between feudal and religious leaders, as well as mistrust between tribes, meant that these forces could not be mobilised to strike decisively against the French. Even with much inferior forces, the better-armed French were able to relieve towns under siege.[61] Mohamed Mokrani died on 5 May 1871 at Oued Soufflat, near Bouira, during a battle against a French army, and his body was immediately to the Kalâa of Ait Abbas.[70] The Kalaa itself, impregnable since the 16th century, surrendered on 22 July 1871. Boumezrag Mokrani, brother and successor of Mohamed Mokrani, struggled to pursue the rebellion in Kabylie, and then in the Hodna. Seeking to escape with his followe s to Tunisia, he was finally arrested at Ouargla on 20 January 1872.[69] the suppression and expropriation of the Mokranis marked the final extinction of their political role and their dominion over the region.[71]

Relations with neighbours

Spain

The Kingdom of Ait Abbas owed its founding to the withdrawal of the Hafsid Emir of Béjaïa, Aberrahmane, in 1510, following the conquest of the city by the Spanish under Pedro Navarro. Abderrahmane retreated to the Hautes Plaines, from where, centuries before, Zirid and Hammadid power had originated. This base allowed him to shelter from Spanish raids and organise a resistance to prevent them penetrating more deeply unto the country.[72][73] However, with the arrival and growing influence of the Ottoman Empire in Algiers, he gradually established relations with the Spanish based in Béjaïa, and eventually entered into a formal alliance with them. This provoked the hostility of the Regency of Algiers which sent an expedition against him in 1516, prompting him to break the alliance with Spain.[74] After the fall of Béjaïa to Salah Raïs in 1555, Abderrahmane's successor Abdelaziz acquired artillery and welcomed a 1000-strong Spanish militia to reinforce his armies, particularly during the Second Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbes (1559).[75][76] However, after the Battle of Djerba in 1560, Spanish power was significantly reduced by the Ottomans, and while they retained control of Oran, the Spanish no longer pursued ambitions in eastern Algeria. Nevertheless, the Kingdom of Ait Abbas maintained an ambassador in Spain[77] as well as at the Ottoman court, ensuring that the kabyle language had a presence outside its homeland.[78]

Kingdom of Kuku

The Kingdom of Kuku established itself in Kabylie on the other side of the Soummam valley, where it became a rival of the Kingdom of the Ait Abbas for control of the region. This division gave an advantage to the Ottomans in Algiers.[79] The Kingdom of Kuku, led by Ahmed Belkadi, was allied to the Ottomans and helped them establish the Regency before 1519. That year, to counter the Regency's growing influence, Belkadi allied himself with the Hafsid sultan of Tunis and inflicted a serious defeat on Hayreddin Barbarossa.[80] This victory opened the gates of Algiers to him from 1519 to 1527.[81] These developments did not lead to any degree of rapprochement between the two Kabyle kingdoms. In 1559, Kuku formed an alliance with Algiers to limit the growing influence of the Sultan of the Kalaa.[75]

Regency of Algiers

In the 16th century, the sultan of the Kalâa was a source of constant concern to the Regency of Algiers, considering his important influence in Kabylie, the high plateau of the interior and the Sahara. They were briefly allies in the early 16th century when the Kingdom of Kuku occupied Algiers from 1520-1527, as well as for the expeditions to Tlemcen in 1551 and Touggourt in 1552. However, despite these alliances, there were many armed conflicts in the late 16th and the early 17th centuries. Algiers could not succeed in taking the Kalâa, and had to content itself with receiving tribut in recognition of its pre-eminence.[75][82] In the 17th century sultan Bouzid, strengthened by his military success, was able to require Algiers to pay him the "ouadia" to secure passage of its troops, merchants and dignitaries because of his control of the Iron Gates pass through the Biban mountains. This was the only instance in the country where the Turkish-held cities paid tribute to the local tribespeople.[83] This relative independence continued until the end of the 18th century, when divisions and internal battles among the Mokranis meant that most of them ended up as vassals of Constantine, which granted them titles of caïd and assigned them to rule over tribes in the Hautes Plaines. The Beys of Constantine cleverly cultivated minor branches of the Mokrani family, so as to ensure that the Sheikh of the Medjana was not a serious threat. The matrimonial alliance of the Mokranis with Ahmed Bey caused further disorder.[84]

The Sahara

From the 16th century, sultan Ahmed Amokrane pushed his forces into the Sahara where they clashed with the Douaouida confederation and conquered their lands.[85] He managed to command the loyalty of some of the local tribes and appointed a khalifa in the South.[86][24] However control over the Zibans, Ouargla and Touggourt dissipated after the death of Ahmed Amokrane and his successor Sidi Naceur abandoned the South, where henceforth the Douaouida chief Ahmed Ben Ali, known as Bou Okkaz, who dominated the region. he gave his daughter in marriage to Sidi Naceur and his grandson Ben Sakheri was the victor at the battle of Guidjel (1638) against the Bey of Constantine.[86] · [87] During the following centuries, commercial relations were maintained between the Aït Abbas, the Aït Yaala and the oases of the asouth, particularly Bou Saâda.[88]

Social basis of power

Map of the Béjaïa region with the tribes under Mokrani rule, 17th-18th century. Tribes paying tribute to the Mokrani shown in orange

Traditional kabyle society was an agglomeration of "village republics" running their own affairs through village councils ("tajamâat"), gathered together in tribes.[72] These tribes maintained links with the prevailing local dynasties, such as the Zirids, Hammadids and Hafsids. They were also organised into domains that the Spanish, after taking Béjaïa, termed the "kingdoms" of Aït Abbas, Kuku and Abdeldjebbar.[note 2] Both Kuku and the Kingdom of Ait Abbas came into being in a society where the norm was for small self-governing 'republics', jealously guarding their independence. There were however earlier historic examples of larger Kabyle polities being formed; for example, during the Hafsid period, around 1340, a woman leader had wield power, supported by her sons, among the Aït Iraten.[72]

Rural kabyle communities had to preserve their autonomy, particularly in terms of resources such as their forests, from the hegemony of local lords, while at the same time they had to support them sufficiently in the face of pressure from the central government of the Regency of Algiers.[72] The Aït Abbas, Hachem and Ayad tribes were recognised as tributaries of the Mokrani, and the Deys of Algiers tacitly recognised the independence of the Mokranis by not demanding tax revenues from these tribes.[89] The kabyle "village republics" based in their "tajamâat" were neither an immutable structure in kabyle society nor a form of kabyle particularism but a result of the fall of the Hafsid state in the region.[72][90]

The Mokrani (or in kabyle the "Aït Mokrane") were a warrior aristocracy which was not alone in seeking to establish and maintain its authority over the people. Religious movements also exerted considerable power, most notably that of the family of Ben Ali Chérif in the Soummam valley.[71] Marabouts and religious confraternities also played a major role, among them the Rahmaniyya, founded in 1774. It was with this fraternity's support that Mohamed Mokrani launched his revolt in 1871.[91] Support was not uniform however. Hocine El Wartilani, an 18th-century thinker from the Aït Ourtilane tribe, issued a formal opinion in 1765, circulated among the kabyles under Mokrani rule, which said they had grown tyrannical to the people to avenge themselves for the loss of their supremacy in the region following the assassination of their forefather Sidi Naceur Mokrani.,[note 3] and his descendants carried out a form of vengeance on the region.[92]

For their part, following on the practices of their ancestors (in Berber "imgharen Naït Abbas"), the Mokranis helped the local population by providing a minimum level of assistance to those who came to the Kalâa to seek help. This tradition dated back to the first Aït Abbas princes.[93] It appears that the Aït Abbas tribe itself was founded at the same time as the Kalâa, shortly after the fall of Béjaïa to the Spanish in 1510. The Hafsid emirs of Béjaïa set themselves up on the Kalâa and gathered around them a new tribe of loyalists in their chosen centre of power.[94] In the 17th century, kabyle society was profoundly changed by the influx of people fleeing the authority of the Regency; this helped to give it the characteristics of an overpopulated mountain region which it was to retain until the period of independence.[90]

Written culture

Copy of a manuscript on the genealogy of the saint Sidi Yahia El Aidli.

The Kalâa of Ait Abbas was known in Berber as "l'qelâa taƐassamt", or "fortress of wonders" , indicating its status as a prestigious centre in the region.[95] Indeed, the Kalâa and the Buban mountains were the seat of an active intellectual life.[96]

Although kabyle culture was predominantly oral, a network of zaouïas, were home to a substantial written culture as well.[97] The most noteworthy example was the Aït Yaâla tribe, whose reputation was summed up in the local saying "In the lands of the Beni Yaala, religious scholars ("oulema") grow like the grass in Spring." Some compared the level of learning of the Aït Yaala with that of the universities of Zitouna in Tunis or Qaraouiyine in Fès. The surprising degree of literacy and the flourishing of a written culture may be attributed in part to the way urban elites from the coastal cities used the mountains as a refuge in hostile political conditions. Links with Béjaïa were important in this respect, as was the influx of refugees from Andalusia after the Reconquista. It certainly predates any Ottoman influence.[98]

The use of writing was not however confined to an educated elite. Before the French conquest of Algeria, nearly all of the Aït Yaala owned deeds to their land or contracts drawn up by cadis or other literate people. Laurent-Charles Féraud likewise reported that individuals still held property deeds issued by the administration of Ahmed Amokrane in the 19th century.[25] The 19th century library of Cheikh El Mouhoub is another indication of the extent of literacy in Berber society; it contained more than 500 manuscripts from different periods on subjects including fiqh, literature, astronomy, mathematics, botany and medicine.

Among the Aït Yaala, libraries were known in kabyle as "tarma". This word is certainly of Mediterranean origin and is used from Iraq to Peru to designate libraries. It is testament not only to the cultural enrichment brought to the region by refugees from Andalusia and of literati from Béjaïa, but also of the extent to which local people travelled; far from being secluded in their villages, they had links with the wider world.[98]

Architecture

Interior courtyard of a house in the Kalâa (c. 1865).

The villages of the region are characterised by a certain urban refinement unusual in Berber villages, and this legacy originates with the Kingdom of Ait Abbas. The houses of Ighil Ali are similar to those in the casbah of Constantine; the houses are of two stories, with balconies and arcades. The streets are narrow and paved, in contrast to the spaciousness of the dwellings. The doorways are built of hardwood, studded with floral and other patterns.[99]

The houses of the Kalâa are described as being of stone and tiled.[100] According to Charles Farine who visited in the nineteenth century, the houses were spacious, with interior courtyards, shaded with trees and climbing plants which reached the balconies. The walls were covered with lime. The Kalâa echoed some of the architectural features of kabyle villages, on a larger scale, with the addition of fortifications, artillery posts and watchtowers, barracks, armouries and stables for the cavalry.[101] The Kalâa also has a mosque with Berber-Andalusian architecture, still preserved.[102]

The building of military installations took place largely under Abdelaziz El Abbès in the sixteenth century, including the casbah mounted with four wide-calibre cannon[42] and the curtain wall, ere ted after the First Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbes (1553).[103]

Today the Kalâa is in a degraded condition because of bombardments during fighting with the French, and 3/5 of the buildings are in ruins.[104]

Economy

Natural resources and agriculture

The traditional kabyle economy which prevailed until the 19th century was based on a relative poverty of natural resources, combined with a relatively high population density - a contrast which had been noted since the time of Ibn Khaldun. The land was mountainous with little arable space, and agriculture was vulnerable to natural disasters such as drought as well as political events such as armed conflict. This fragile system maintained its viability through specific forms of social organisation, including how land was inherited.[105] While horticulture and arboriculture were key activities however, the poverty of resources meant that there was also a great deal of artisanal and commercial activity in the region.[106][107]

The Mokrani extended their power from the Kalaa to the Medjana plain (known in kabyle as the Tamejjant)[95] to the south, which was more extensive and more fertile than their home territory.[108] Here, at a large scale, they cultivated olives for their oil which was traded as well as used in local crafts. Cereals, figs and grapes were also grown and dried for storage and trade. Their territory also produced a great quantity of prickly pear. Sheep were also raised for wool.[109]

These conditions allowed for division of labour and specialism between the mountainous areas and the plains, with exchange taking place principally in the market towns. In times of peace, this trade was of great benefit to the Kabyles. Agricultural work was undertaken almost exclusively within the family unit, without use of additional labour except in exceptional cases where families might provide mutual aid for each other. This agricultural practice was known as tiwizi. The scarcity of arable soil compelled the peasants to exploit the smallest plots. Trees and grasses played a key role, allowing them to produce fruits and olive oil and raise cattle, sheep and goats. Links with the landowners of the plains kept them provisioned with wheat and barley, their staple foods.[110][111] A junior marabout branch of the Mokrani family, near Béjaïa, controlled the rights (known as the karasta) to exploit local forests on behalf of the Ottoman navy.[97]

Commerce

There were a number of weekly berber markets, which served as places of local exchange. The Aït Abbas had four, including the Thursday market at the Kalâa. To the south, the Sunday market at Bordj Bou Arreridj drew merchants and clients from a wide surrounding area.[112]

The Kingdom of the Ait Abbas controlled the Iron Gates pass on the Algiers-Constantine road, and levied the ouadia on those passing through it.[113][87] The Kalaa also stood on the 'Sultan's Road' (triq sultan) which linked Béjaïa with the south and had formed the route of the mehalla, the regular tax-raising expedition, since the Middle Ages.[114] By the sixteenth century the kingdom's merchants (ijelladen) were trading grain with the Spanish enclave of Béjaïa,[113] while trans-Saharan trade, centred on Bousaada and M'sila, was conducted by the merchants of Aït Abbas, Aït Yaala and Aït Ourtilane. The kabyle tribes exported oil, weapons, burnous, soap and wooden utensils, exchanging them for wool, henna and dates.[115]

Commercial links existed likewise with the cities under the Regency of Algiers, notably Constantine, where Aït Yaala, Aït Yadel et Aït Ourtilane merchants did business. Aït Abbas armourers supplied Ahmed Bey with weapons.[116] Like the Aït Yaala and the Aït Ourtilane, the Aït Abbas maintained a fondouk in Constantine. Although the Aït Yaala also operated one in Mascara,[114] the merchants preferred Béjaïa, their natural outlet to the Mediterranean. Overseas, the Aït Abbas and Aït Ourtilane sold their bournouses in Tunis and in Morocco.[117][108][118] Overseas trade also brought materials of superior quality to the Kingdom, such as European iron.[119]

Arts and crafts

Door from the Ighil Ali region.

The Aït Abbas tribe was famed for its riches, its commerce and its manufactures, and it is likely that the Mokrani family invested in a wide range of these,[120] including the manufacture of firearms.[109]

As well as farming, the blacksmiths (iḥeddaden) of the Kabyle tribes had always manufactured whatever tools they needed locally, while also using this activity to generate surplus income. Iron working and other metal craft existed in several tribes, and indeed some, like the Aït Abbas, specialised in it.

The forests of Kabylie allowed for the extraction of timber, used in the craft manufacture of doors, roofs, furniture and chests and exported to the shipyards of the Tunisian, Egyptian and Ottoman navies. Local wool supported cottage industries, mostly of women, in the making of clothes such as the burnous, carpets and covers. Other industries included pottery, tiles, basket weaving, salt extraction, soap, and plaster.[121]

See also

- First Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbes (1553)

- Second Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbes (1559)

Bibliography

Periodicals

- Dahbia Abrous, « Kabylie : Anthropologie sociale », Encyclopédie berbère, vol. 26, 2011, p. 4027-4033 (read online [archive])

- Djamel Aïssani, « Écrits de langue berbère de la collection de manuscrits Oulahbib (Béjaïa) », Études et documents berbères, no 15-16, 1998, p. 81-99 (read online [archive])

- Dehbia Akkache-Maacha, « Art et Artisanat traditionnels de Kabylie », Campus, Université Mouloud Mammeri de Tizi Ouzou, faculté des sciences économiques et de gestion, no 12, décembre 2008, p. 4-21 (ISSN 1112-783X, read online [archive] [PDF])

- Nedjma Abdelfettah Lalmi, « Du mythe de l'isolat kabyle », Cahiers d'études africaines, no 175, 2004, p. 507-531 (read online [archive])

- « Ighil-Ali », Encyclopédie berbère, no 24, 2011, p. 3675-3677 (read online [archive])

- Djamil Aïssani, « Le Milieu Intellectuel des Bibans à l'époque de la Qal`a des Beni Abbes », Extrait de conférence à l'occasion du 137e anniversaire de la mort d'El Mokrani, 2008

- Ghania Moufok, « Kabylie, sur les sentiers de la belle rebelle », Géo « Algérie La renaissance », no 332, 2006, p. 100-108

- Saïd Doumane, « Kabylie : Économie ancienne ou traditionnelle », Encyclopédie berbère, no 26, 2004, p. 4034-4038 (read online [archive])

Works

Julien, Charles-André (1964). Histoire de l'Algérie contemporaine: La conquête et les débuts de la colonisation (1827-1871) (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Presses universitaires de France..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

Benoudjit, Youssef (1997). La Kalaa des Béni Abbès au XVIe siècle (in French). Alger: Dahlab. ISBN 9961611322.

Allioui, Youcef (2006). Les Archs, tribus berbères de Kabylie: histoire, résistance, culture et démocratie (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-296-01363-5.

Allioui, Youcef (2013). Histoire d'amour de Sheshonq 1er: Roi berbère et pharaon d'Egypte - Contes et comptines kabyles (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-296-53739-1.

Roberts, Hugh (2014). Berber Government: The Kabyle Polity in Pre-colonial Algeria. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845112516.

Mahé, Alain (2001). Histoire de la Grande Kabylie, XIXe-XXe siècles: anthropologie historique du lien social dans les communautés villageoises. Saint-Denis: Bouchène. ISBN 2912946123.- Tahar Oussedik, Le Royaume de Koukou, Alger, ENAG édition, 2005, 91 p. (

ISBN 9789961624081) - Dominique Valérian, Bougie, port maghrébin, 1067-1510, Rome, Publications de l'École française de Rome, 2006, 795 p. (

ISBN 9782728307487, read online [archive]) - Smaïn Goumeziane, Ibn Khaldoun, 1332-1406: un génie maghrébin, Alger, EDIF 2000, 2006, 189 p. (

ISBN 2352700019) - Mouloud Gaïd, Les Beni-Yala, Alger, Office des publications universitaires, 1990, 180 p.

- Tassadit Yacine-Titouh, Études d'ethnologie des affects en Kabylie, Paris, Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, 2006, 177 p. (

ISBN 978-2735110865) - Bernard Bachelot, Louis XIV en Algérie : Gigeri 1664, Monaco, Rocher, 2003, 460 p. (

ISBN 2268048322) - Jean Morizot, Les Kabyles : Propos d'un témoin, Paris, Centre des hautes études sur l'Afrique et l'Asie modernes (diff. Documentation française), coll. « Publications du CHEAM », 1985, 279 p. (

ISBN 2-903-18212-4 et 2-747-51027-1, read online [archive]) - Pierre Montagnon, La conquête de l'Algérie : 1830-1871, Paris, Pygmalion Editions, coll. « Blanche et rouge », 1997, 450 p. (

ISBN 978-2857042044) - Mahfoud Kaddache, Et l'Algérie se libéra, Paris, Paris-Méditerranée, 2003, 235 p. (

ISBN 2842721799) - Mouloud Gaïd, Chroniques des Beys de Constantine, Alger, Office des publications universitaires, 1978, 160 p.

Old secondary sources

Rinn, Louis (1891). Histoire de l'insurrection de 1871 en Algérie. Algiers: Librairie Adolphe Jourdan.- Laurent-Charles Féraud, Histoire Des Villes de la Province de Constantine : Sétif, Bordj-Bou-Arreridj, Msila, Boussaâda, vol. 5, Constantine, Arnolet, 1872 (réimpr. 2011), 456 p. (

ISBN 978-2-296-54115-3)

Primary sources

- Louis Piesse, Itinéraire historique et descriptif de l'Algérie, comprenant le Tell et le Sahara : 1830-1871, Paris, Hachette, 1862, 511 p.

- Ernest Carette, Études sur la Kabilie, Alger, Impr. nationale, 1849, 508 p.

- Charles Farine, À travers la Kabylie, Paris, Ducrocq, 1865, 419 p. (read online [archive])

- Ernest Mercier, Histoire de l'Afrique septentrionale (Berbérie) : depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à la conquête française (1830), vol. 3, Paris, Leroux, 1891, 636 p.

- Recueil des notices et mémoires de la Société archéologique de Constantine, vol. 44, Constantine, Arnolet, 1910, 407 p.

Contemporay sources

- (es) Luis Del Mármol, Descripciôn General de Africa : sus guerras y vicisitudes, desde la Fundación del mahometismo hasta el año 1571, Venise, 1571, 582 p. (read online [archive])

- (es) Diego De Haëdo, Topographia e historia general de Argel : repartida en cinco tratados, do se veran casos estraños, muertes espantosas, y tormentos exquisitos, Diego Fernandez de Cordoua y Ouiedo - impressor de libros, 1612, 420 p. (read online [archive])

- (ar) Hocine El Wartilani, Rihla : Nuzhat al-andhar fi fadhl 'Ilm at-Tarikh wal akhbar, 1768

- Jean André Peyssonnel, Voyages dans les régences de Tunis et d'Alger, vol. 1, Librairie de Gide, 1838, 435 p. (read online [archive])

Notes

^ according to Jean-André Peyssonnel who travelled into the Biban mountains in 1725 during Bouzid's reign

^ According to (Lalmi 2004), this latter kingdom was founded in the valley of the Soummam River some 30km from Béjaïa.

^ this Sultan was the victim of an Aït Abbas plot in 1600 because of his unpopular rule.

References

^ ab Afrique barbaresque dans la littérature française aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles (l') Par Guy Turbet-Delof page 25

^ Amokrane signifie en kabyle chef, grand.

^ Le premier est un certain Abu Zakariya vers 1285, à ne pas confondre avec le sultan hafside du même nom, puis Abou el Baqa' en 1301 et Abu Bakr, lui-même émir de Constantine, en 1312.

^ Souvent émirs de l'administration hafside ou princes hafsides eux-mêmes.

^ Goumeziane 2006, p. 19

^ Valérian 2006 - Chapitre 1 : Bougie, un pôle majeur de l'espace politique maghrébin, p. 35-101 (read online)

^ Benoudjit 1997, p. 85

^ Féraud 1872, p. 208-211.

^ Morizot 1985, p. 57

^ Allioui 2006, p. 205

^ Féraud 1872, p. 214

^ Gaïd 1978, p. 9

^ Féraud 1872, p. 217

^ Féraud 1872, p. 219

^ Roberts 2014, p. 195

^ Féraud 1872, p. 220-221

^ Féraud 1872, p. 221

^ Benoudjit 1997, p. 4

^ ab Rinn 1891, p. 13

^ Féraud 1872, p. 222-223

^ Benoudjit 1997, p. 243

^ Féraud 1872, p. 226

^ Roberts 2014, p. 192

^ ab (Féraud 1872, p. 229)

^ ab (Féraud 1872, p. 232)

^ (Gaïd 1978, p. 14)

^ ab (Rinn 1891, p. 12)

^ (Benoudjit 1997, p. 289)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 14)

^ (Féraud 1872, p. 259)

^ (Féraud 1872, p. 261)

^ (Féraud 1872, p. 269)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 13)

^ (Gaïd 1978, p. 10)

^ (Société Constantine 1910, p. 155)

^ (Bachelot 2003, p. 304)

^ (Bachelot 2003, p. 276)

^ (Bachelot 2003, p. 228)

^ (Bachelot 2003, p. 427)

^ (Bachelot 2003, p. 371)

^ (Société Constantine 1910, pp. 180–182)

^ ab (Société Constantine 1910, p. 151)

^ ab (Rinn 1891, p. 15)

^ (Féraud 1872, p. 250)

^ (Féraud 1872, p. 277)

^ ab (Rinn 1891, pp. 16–17)

^ (Féraud 1872, p. 262)

^ abc (Rinn 1891, p. 17)

^ (Féraud 1872, p. 273)

^ (Féraud 1872, pp. 301–303)

^ (Rinn 1891, pp. 17–19)

^ (Rinn 1891, pp. 19–20)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 20)

^ (Gaïd 1978, p. 114)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 21)

^ (Montagnon 1997, p. 250)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 22)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 24)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 25)

^ (Rinn 1891, pp. 26–27)

^ ab (Montagnon 1997, pp. 251–253)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 29)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 31)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 32)

^ (Rinn 1891, pp. 35–36)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 37)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 50)

^ (Montagnon 1997, p. 415)

^ ab (Rinn 1891, p. 647)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 350)

^ ab (Abrous 2011, p. 2)

^ abcde (Lalmi 2004, pp. 515–516)

^ (Benoudjit 1997, p. 104)

^ Cite error: The named referenceFéraud p214was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

^ abc Cite error: The named referenceRoberts192was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 11)

^ (Allioui 2006, p. 79)

^ (Allioui 2013, p. 18)

^ (Benoudjit 1997, p. 171)

^ (Féraud 1872, p. 216)

^ (Roberts 2014, p. 152)

^ (Rinn 1891, pp. 10–13)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 13)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 18)

^ (Mercier 1891, p. 206)

^ ab (Mercier 1891, p. 207)

^ ab Cite error: The named referenceharvspwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

^ (Carette 1849, pp. 406–407)

^ (Rinn 1891, p. 16)

^ ab (Yacine-Titouh 2006, pp. 12–13)

^ (Lalmi 2004, p. 517)

^ (Féraud 1872, p. 239)

^ (Allioui 2006, p. 97)

^ (Roberts 2014, p. 167)

^ ab (Allioui 2006, p. 113)

^ (Aïssani 2008)

^ ab (Lalmi 2004, p. 521)

^ ab (Lalmi 2004, p. 524)

^ (Ighil Ali 2011)

^ (Piesse 1862, p. 388)

^ (Benoudjit 1997, p. 139)

^ (Géo 2006, p. 108)

^ (Benoudjit 1997, p. 244)

^ (Kaddache 2003, p. 54)

^ (Doumane 2004, p. 2)

^ (Roberts 2014, p. 34)

^ (Benoudjit 1997, p. 330)

^ ab (Morizot 1985, p. 59)

^ ab (Carette 1849, p. 357)

^ (Doumane 2004, p. 3)

^ (Morizot 1985, p. 58)

^ (Carette 1849, p. 358)

^ ab (Benoudjit 1997, p. 86)

^ ab (Lalmi 2004, p. 520)

^ (Carette 1849, p. 406)

^ (Ighil Ali 2014)

^ (Carette 1849, p. 407)

^ (Morizot 1985, p. 122)

^ (Benoudjit 1997, p. 336)

^ (Benoudjit 1997, p. 334)

^ (Doumane 2004, p. 4)