Béjaïa

Béjaïa بجاية / Bgayeth / Bgayet | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

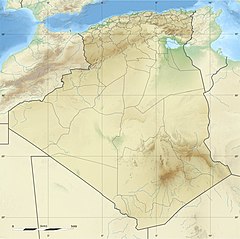

Location of Béjaïa, Algeria within Béjaïa Province | |

Béjaïa Location of Béjaïa, Algeria within Béjaïa Province | |

| Coordinates: 36°45′N 5°04′E / 36.750°N 5.067°E / 36.750; 5.067Coordinates: 36°45′N 5°04′E / 36.750°N 5.067°E / 36.750; 5.067 | |

| Country | |

| Province | Béjaïa Province |

| District | Béjaïa District |

| Area | |

| • Total | 120.22 km2 (46.42 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 949 m (3,114 ft) |

| Population (2008 census) | |

| • Total | 177,988 |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (3,800/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| Postal code | 06000 |

| Climate | Csa |

Béjaïa (Arabic: بِجَايَة, Bijayah; Berber languages: Bgayet, Bgayeth), formerly Bougie and Bugia, is a Mediterranean port city on the Gulf of Béjaïa in Algeria; it is the capital of Béjaïa Province, Kabylia. Béjaïa is the largest principally Kabyle-speaking city in the Kabylie region of Algeria. The history of Béjaïa explains the diversity of the local population.

Contents

1 Geography

2 History

2.1 Antiquity and Byzantine era

2.2 Muslim and feudal rulers

2.3 French colonial rule

2.3.1 Battle of Béjaïa

2.4 Algerian republic

3 Ecclesiastical history

3.1 Titular see of Bugia

4 Climate

5 Demography

6 Economy

7 Friendly relationship

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

Geography

Monkey Peak (Pic des singes).

The town is overlooked by the mountain Yemma Gouraya, whose profile is said to resemble a sleeping woman. Other nearby scenic spots include the Aiguades beach and the Pic des Singes (Monkey Peak); the latter site is a habitat for the endangered Barbary macaque, which prehistorically had a much broader distribution than at present. All three of these geographic features are located in the Gouraya National Park. The Soummam river runs past the town.

Under French rule, it was formerly known under various European names, such as Budschaja in German, Bugia in Italian, and Bougie [buˈʒi] in French. The French and Italian versions, due to the town's wax trade, eventually acquired the metonymic meaning of "candle".[1]

History

Antiquity and Byzantine era

The Western Roman empire in the second century AD during the reign of Hadrian. Saldae can be seen on the south coast of the Mediterranean.

According to Al-Bakri, the bay was first inhabited by Andalusians.[2]

Béjaïa stands on the site of the ancient city of Saldae, a minor port in Carthaginian and Roman times, in an area at first inhabited by Numidian Berbers and founded as a colony for old soldiers by emperor Augustus. It was an important town and a bishopric in the province of Mauretania Caesariensis, and later Sitifensis.

Coin of the Hafsids, with ornamental Kufic script, from Béjaïa hi, 1249-1276.

In the fifth century, Saldae became the capital of the short-lived Vandal Kingdom of the Germanic Vandals, which ended in about 533 with the Byzantine conquest, which established an African prefecture and later the Exarchate of Carthage.

Muslim and feudal rulers

After the 7th-century Muslim conquest, it was refounded as "Béjaïa"; the Hammadid dynasty made it their capital, and it became an important port and centre of culture.

Historic map of Algiers and Béjaïa by Piri Reis

The son of a Pisan merchant (and probably consul), posthumously known as Fibonacci (c. 1170 – c. 1250), there learned about Muslim mathematics (which he called "Modus Indorum") and Hindu-Arabic numerals. He introduced these and modern mathematics into medieval Europe.[3] A mathematical-historical analysis of Fibonacci's context and proximity to Béjaïa, an important exporter of wax in his time, has suggested that it was actually the bee-keepers of Béjaïa and the knowledge of the bee ancestries that truly inspired the Fibonacci sequence rather than the rabbit reproduction model as presented in his famous book Liber Abaci.[4]

According to Muhammad al-Idrisi, the port was, in the XIth century, a market place between Mediterranean merchant ships and caravans coming from the Sahara desert. Christian merchants settled fundunqs (or Khans) in Bejaïa. The Italian city of Pisa was closely tied to Béjaïa, where it built one of its two permanent consulates in the African continent.[2]

In 1315, Ramon Llull died as a result of being stoned at Béjaïa,[5][6] where, a few years before, Peter Armengaudius (Peter Armengol) is reputed to have been hanged.[6][7]

After a Spanish occupation (1510–55), the city was taken by the Ottoman Turks in the Capture of Bougie in 1555. For nearly three centuries, Béjaïa was a stronghold of the Barbary pirates (see Barbary States). The city consisted of Arabic-speaking Moors, Moriscos and Jews increased by Jewish refugees from Spain, with the Berber peoples not in the city but occupying the surrounding villages and travelling to the city occasionally for the market days.

City landmarks include a 16th-century mosque and a fortress built by the Spanish in 1545.

A picture of the Orientalist painter Maurice Boitel, who painted in the city for a while, can be found in the museum of Béjaïa.

French colonial rule

It was captured by the French in 1833 and became a part of colonial Algeria. Most of the time it was the seat ('sous-préfecture') of an arrondissement (mid 20th century, 513,000 inhabitants, of whom 20,000 'Bougiates' in the city itself) in the Département of Constantine, until Bougie was promoted to département itself in 1957.

Battle of Béjaïa

During World War II, Operation Torch landed forces in North Africa, including a battalion of the British Royal West Kent Regiment at Béjaïa on November 11, 1942.

That same day, at 4:40 PM, a German Luftwaffe air raid struck Béjaïa with thirty Ju 88 bombers and torpedo planes. The transports Awatea and Cathay were sunk and the monitor HMS Roberts was damaged. The following day, the anti-aircraft ship SS Tynwald was torpedoed and sank, while the transport Karanja was bombed and destroyed.[8]

Algerian republic

After Algerian independence, it became the eponymous capital of Béjaïa Province, covering part of the eastern Berber region Kabylia.

Ecclesiastical history

With the spread of Christianity, Saldae became a bishopric. Its bishop Paschasius was one of the Catholic bishops whom the Arian Vandal king Huneric summoned to Carthage in 484 and then exiled.

Christianity survived the Arab conquest, the disappearance of the old city of Saldae, and the founding of the new city of Béjaïa. A letter from Pope Gregory VII (1073–1085) exists, addressed to clero et populo Buzee (the clergy and people of Béjaïa), in which he writes of the consecration of a bishop named Servandus for Christian North Africa.[5][6][9]

No longer a residential bishopric, Saldae (v.) is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[10] and still has incumbents by that title (mostly of the lowest (episcopal) rank, some of the intermediary archiepiscopal rank).

Titular see of Bugia

This titular see was for a long time, alternatively and concurrently with the city's authentic Roman Latin name Saldae (v.), called Bugia, the Italian language form (used in the Roman Curia) of Béjaïa.

The 'modern' form and title, Bugia, seems out of use, after having had the following incumbents, all of the lowest (episcopal) rank :

- Miguel Morro (1510 – ?), as Auxiliary Bishop of Mallorca (Balearic Spain) (1510 – ?)

- Fernando de Vera y Zuñiga, Augustinians (O.E.S.A.) (1614.02.17 – 1628.11.13), as Auxiliary Bishop of Badajoz (Spain) (1614.02.17 – 1628.11.13); later Metropolitan Archbishop of Santo Domingo, finally Archbishop-Bishop of Cusco (Peru) (1629.07.16 – death 1638.11.09)

- François Perez (1687.02.05 – death 1728.09.20), as Apostolic Vicar of Cochin (Vietnam) (1687.02.05 – 1728.09.20)

- Antonio Mauricio Ribeiro (1824.09.27 – death ?), as Auxiliary Bishop of Évora (Portugal) (1824.09.27 – ?)

George Hilary Brown (5 June 1840 until 22 April 1842), as first and only Apostolic Vicar of Lancashire District (England) (1840.06.05 – 1850.09.29), later Titular Bishop of Tlous (1842.04.22 – 1850.09.29), promoted first bishop of successor see Liverpool (1850.09.29 – 1856.01.25)

Climate

Béjaïa, like most cities along the coast of Algeria, has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa), with very warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters.

| Climate data for Béjaïa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.7 (81.9) | 32.0 (89.6) | 37.0 (98.6) | 33.0 (91.4) | 37.3 (99.1) | 42.8 (109.0) | 44.7 (112.5) | 47.6 (117.7) | 42.5 (108.5) | 40.0 (104.0) | 37.4 (99.3) | 33.0 (91.4) | 47.6 (117.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 16.4 (61.5) | 16.8 (62.2) | 17.7 (63.9) | 19.3 (66.7) | 22.0 (71.6) | 25.3 (77.5) | 28.7 (83.7) | 29.3 (84.7) | 27.8 (82.0) | 24.3 (75.7) | 20.3 (68.5) | 16.9 (62.4) | 22.1 (71.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.1 (53.8) | 12.3 (54.1) | 13.1 (55.6) | 14.7 (58.5) | 17.6 (63.7) | 21.0 (69.8) | 24.0 (75.2) | 24.8 (76.6) | 23.2 (73.8) | 19.7 (67.5) | 15.8 (60.4) | 12.7 (54.9) | 17.6 (63.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) | 7.6 (45.7) | 8.5 (47.3) | 10.1 (50.2) | 13.1 (55.6) | 16.6 (61.9) | 19.3 (66.7) | 20.2 (68.4) | 18.5 (65.3) | 15.0 (59.0) | 11.2 (52.2) | 8.4 (47.1) | 13.0 (55.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) | −4.0 (24.8) | −0.1 (31.8) | 2.0 (35.6) | 5.8 (42.4) | 7.8 (46.0) | 13.0 (55.4) | 11.0 (51.8) | 11.0 (51.8) | 8.0 (46.4) | 1.6 (34.9) | −2.4 (27.7) | −4.0 (24.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 99.7 (3.93) | 85.9 (3.38) | 100.4 (3.95) | 70.7 (2.78) | 41.2 (1.62) | 16.2 (0.64) | 5.8 (0.23) | 13.0 (0.51) | 40.4 (1.59) | 89.5 (3.52) | 99.7 (3.93) | 135.0 (5.31) | 797.5 (31.39) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78.5 | 77.6 | 77.9 | 77.9 | 79.9 | 76.9 | 75.0 | 74.6 | 76.4 | 76.3 | 75.3 | 76.0 | 76.9 |

| Source #1: NOAA (1968-1990)[11] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: climatebase.ru (extremes, humidity)[12] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Cap Carbon Lighthouse in 2013 | |

Algeria | |

| Location | Cap Carbonbr Béjaïa |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°46′34.25″N 5°6′14.83″E / 36.7761806°N 5.1041194°E / 36.7761806; 5.1041194 |

| Year first constructed | 1906[13] |

| Construction | masonry tower |

| Tower shape | cylindrical tower with balcony and lantern rising from the keeper’s house |

| Markings / pattern | white tower, black lantern roof |

| Tower height | 14.60 metres (47.9 ft)[13] |

| Focal height | 224.10 metres (735.2 ft)[13] |

| Range | 29 nautical miles (54 km; 33 mi)[13] |

| Characteristic | Fl (3) W 20s.[14] |

Admiralty number | E6572 |

NGA number | 22328 |

ARLHS number | ALG-007[15] |

| Managing agent | Office Nationale de Signalisation Maritime |

| | |

The population of the city in 2008 in the latest census was 177,988.

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1901 | 14,600 |

| 1906 | 17,500 |

| 1911 | 10,000 |

| 1921 | 19,400 |

| 1926 | 15,900 |

| 1931 | 25,300 |

| 1936 | 30,700 |

| 1948 | 28,500 |

| 1954 | 43,900 |

| 1960 | 63,000 |

| 1966 | 49,900 |

| 1974 | 104,000 |

| 1977 | 74,000 |

| 1987 | 114,500 |

| 1998 | 144,400 |

| 2008 | 177,988 |

Economy

Maritime front of Béjaïa: a view of its industrial facilities and the airport.

The northern terminus of the Hassi Messaoud oil pipeline from the Sahara, Béjaïa is the principal oil port of the Western Mediterranean. Exports, aside from crude petroleum, include iron, phosphates, wines, dried figs, and plums. The city also has textile and cork industries.[citation needed]

Cevital has its head office in the city.[17]

The city's soccer team is JSM Béjaïa and currently plays in the Algerian Ligue Professionnelle 2.

Friendly relationship

Béjaïa has an official friendly relationship (protocole d'amitié) with:

Glasgow, Scotland, since 1995

Glasgow, Scotland, since 1995 Brest

Brest Bad Homburg

Bad Homburg

See also

- List of lighthouses in Algeria

Saldae, for Roman history and concurrent Catholic titular see

- Related people

- Abu al-Salt

- Fibonacci

References

^ "Bougie (n)". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 29 November 2012.Etymology: < French bougie wax candle, < Bougie (Arabic Bijiyah), a town in Algeria which carried on a trade in wax

.mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

Available online to subscribers

^ ab Bejaia - Algeria, Muslimheritage.com

^ Stephen Ramsay, Reading Machines: Toward an Algorithmic Criticism, (University of Illinois Press, 2011), 64.

^ Scott, T.C.; Marketos, P. (March 2014), On the Origin of the Fibonacci Sequence (PDF), MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

^ ab Stefano Antonio Morcelli, Africa christiana, Volume I, Brescia 1816, p. 269

^ abc H. Jaubert, Anciens évêchés et ruines chrétiennes de la Numidie et de la Sitifienne, in Recueil des Notices et Mémoires de la Société archéologique de Constantine, vol. 46, 1913, pp. 127-129

^ J. Frank Henderson, "Moslems and the Roman Catholic Liturgical Calendar. Documentation" (2003), p. 18

^ Atkinson 2002.

^ J. Mesnage, L'Afrique chrétienne, Paris 1912, pp. 8 e 268-269

^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013

ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 963

^ "Climate Normals for Béjaïa". Retrieved 11 February 2013.

^ "Béjaïa, Algeria". Climatebase.ru. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

^ abcd "Cap Carbon". Office Nationale de Signalisation Maritime. Ministere des Travaux Publics. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

^ List of Lights, Pub. 113: The West Coasts of Europe and Africa, the Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea and Azovskoye More (Sea of Azov) (PDF). List of Lights. United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. 2015.

^ "Eastern Algeria". The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

^ populstat.info Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

^ "Cevital & vous Archived 12 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine." Cevital. Retrieved on 26 August 2011. "Adresse : Nouveau Qaui Port de -Béjaïa - Algérie"

Atkinson, An Army At Dawn

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Béjaïa. |

(in French) Bgayet.Net

(in French) History of Béjaïa

- GigaCatholic, with titular incumbent biography links

- Google map of Béjaïa