Pedal steel guitar

Modern pedal steel guitar with two necks

The pedal steel guitar is a console-type of steel guitar with pedals and levers added to enable playing more varied and complex music which had not been possible with antecedent steel guitar designs. Like other steel guitars, it shares the ability to play unlimited glissandos (sliding notes) and deep vibratos—characteristics in common with the human voice. Pedal steel is most commonly associated with American country music.

Pedals and knee levers were added to a steel guitar in the 1950s, allowing the performer to play scales without moving the bar and also to push the pedals while striking a chord, making passing notes slur or bend up into harmony with existing notes. The latter creates a unique sound that has been particularly embraced by country and western music—a sound not previously possible on a non-pedal steel guitar of any type.

From its first use in Hawaii in the 19th century, the steel guitar sound became popular in the United States in the first half of the 20th century and spawned a family of instruments designed specifically to be played with the guitar a horizontal position, also known as "Hawaiian-style". The first instrument in this chronology was the Hawaiian guitar also called a lap steel; next was a lap steel with a resonator to make it louder, first made by National and Dobro Corporation. The electric guitar pickup was invented in 1934, allowing steel guitars to be heard equally with other instruments. Electronic amplification enabled subsequent development of the electrified lap steel, then the console steel, and finally the pedal steel guitar.

Playing the pedal steel has unusual physical requirements in requiring simultaneous coordination of both hands, both feet and both knees (knees operate levers on medial and lateral sides of each knee); the only other instrument with similar requirements is the American reed organ. Pioneers in development of the instrument include Buddy Emmons, Bud Isaacs, Zane Beck, and Paul Bigsby. In addition to American country music and Hawaiian music, the instrument is common in sacred music (called Sacred Steel), jazz, Nigerian Music, and Indian music.

Contents

1 Early history and evolution

2 Electrification of the steel guitar

3 Lap steel

4 Lap steel becomes console steel

5 Console steel becomes pedal steel

6 Bud Isaacs: the birth of a new sound in country music

7 Buddy Emmons' contributions to pedal steel

8 The modern pedal steel

9 Pedal steel in other genres

10 See also

11 References

12 External links

Early history and evolution

The instrument's ancestry is traced to the Hawaiian Islands in the late 19th century after the Spanish guitar was introduced there by European sailors[1] and by Mexican vaqueros who came there to herd cattle.[2] Hawaiians who perhaps did not want to take the time to learn how to play a Spanish guitar, re-tuned the instrument so it sounded a major chord when strummed, then thought to be an "unorthodox tuning".[2] This was known as "slack-key" because some of the strings were slackened to tune to a chord.[1] To change chords, they used some smooth object, usually a piece of pipe or metal, sliding it over the strings to the fourth or fifth position, easily playing a three-chord song. To make playing easier, they laid the guitar across the lap and played it while sitting. The problem with playing a traditional Spanish guitar this way was that the steel tone bar strikes against the frets making an unpleasant sound unless played very lightly—this was corrected by raising the strings higher off the fretboard with a piece of metal or wood over the nut.[1] This technique became popular throughout Hawaii.[1]

Kekuku's Hawaiian Quintet

Joseph Kekuku was a Hawaiian from Oahu who became proficient in this style of playing around the turn of the century and popularized it—some sources say he invented the steel guitar.[3] He moved to the United States mainland and became vaudeville performer and also toured Europe performing Hawaiian music.

The Hawaiian style of playing spread to the United States mainland and became popular during the first half of the 20th century, to the degree that it has been called the "Hawaiian craze" which was ignited by several events.[4] One such event was a 1912 Broadway musical show called Bird of Paradise, which featured Hawaiian music and elaborate costumes.[5] The show became a hit and, to ride this wave of success, it was subsequently taken on the road in the U.S. and Europe, eventually spawning a motion picture of the same name.[4] Joseph Kekuku was a member of the show's original cast [6] and toured Europe with the Bird of Paradise show for eight years.[7] The Washington Herald in 1918 stated, "So great is the popularity of Hawaiian music in this country that 'The Bird of Paradise' will go on record as having created the greatest musical fad this country has ever known".[8] Another event fueling the popularity of Hawaiian music was a radio broadcast called "Hawaii Calls" which began broadcasting from Hawaii to the US west coast. It prominently featured the steel guitar and Hawaiian songs sung in English. Subsequently the program was heard worldwide on over 750 stations.[9] One of pedal steel guitar's foremost virtuosos, Buddy Emmons (sample below), at age 11 trained at the "Hawaiian Conservatory of Music" in South Bend, Indiana.[10] The Hawaiian style was adapted to blues music. Blues musicians played a conventional Spanish guitar as hybrid between the two types of guitars, using one finger inserted into a tubular slide or a bottleneck while using frets with the remaining fingers.[1] This is known as "slide guitar". One of the first southern blues musicians to adapt the Hawaiian sound to the blues was "Tampa Red"[11] whose playing, says historian Gérard Herzhaft, "created a style that has unquestionably influenced all modern blues."[11]

The acceptance of the sound of the steel guitar, then referred to as "Hawaiian guitars" or "lap steels", spurred instrument makers to produce them in quantity and create innovations in the design to accommodate this style of playing.[12][13]

Electrification of the steel guitar

Hawaiian lap steel guitars were not loud enough to compete with other instruments, a problem that many inventors were trying to remedy. In Los Angeles in the 1920s, a steel guitar player named George Beauchamp saw some inventions which added a horn, like a megaphone, to steel guitars to make them louder.[14] Beauchamp became interested, and went to a shop near his home to learn more. The shop was owned by a violin repairman named John Dopyera. Dopyera and his brother Rudy, showed Beauchamp a prototype of theirs which looked like a big Victrola horn attached to a guitar, but it was not successful.[14] Their next attempt yielded some success with a resonator cone, resembling a large metal loudspeaker, attached under the bridge of the guitar.[15] Buoyed by their success, Beauchamp joined the Dopyera brothers in forming a company to pursue their invention. The new resonator invention was promoted at a lavish party in Los Angeles and demonstrated by the well-known Hawaiian steel player Sol Hoopii. An investor wrote a check for $12,000 that very night.[14]

A factory was built to manufacture metal-body guitars with the new resonators. Money problems and disagreements followed, and the Doperyas won a legal battle against Beauchamp over the company, then went on their own to form "the Dobro Corporation", Dobro being an acronym for DOperya and BROthers. Beauchamp was out of a job. He had been thinking about an "electric guitar" for years, and at least part of the dispute with the Dopyeras was over him spending too much time on the electrification idea and not enough on improving the resonator guitar.[14]

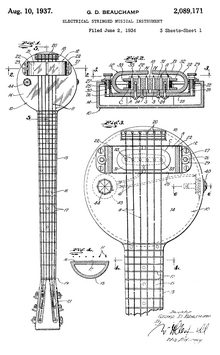

Rickenbacker Fryingpan Patent Diagram

Beauchamp enrolled in electronics courses and, for his first effort, he made a single-string guitar out of a 2x4 piece of lumber and experimented with phonograph pickups, but had no success. He eventually came up with the idea of using two horseshoe magnets encircling the guitar strings like a bracelet, and six small metal rods wrapped with wire to concentrate the magnetic field (one under each guitar string).[16] When connected to an electronic amplifier and loudspeaker, it worked.[14] He enlisted the aid of a skilled craftsman to fashion a guitar neck and body to connect to his device. The final construct, he thought, resembled a frying pan, and that is what the instrument was nicknamed. He applied for patent June 2, 1934 and received it on August 10, 1937.[16] Beauchamp asked a nearby engineer named Adolph Rickenbacker to help manufacture the product and together they founded a company first named "Ro-Pat-In", soon changed to "ElectroString".[14] The guitar brand was called "Rickenbacker" because they thought the name was easier to pronounce than "Beauchamp" (pronounced Beecham) and because Eddie Rickenbacker, Adolph's cousin, was an American pilot and WWI flying ace, well-known name in the U.S. at that time.[14]

In 1931, the great depression was at its worst, and people were not buying guitars; in addition, the patent office delayed on the application, in part because they had no category for the invention—was it a musical instrument or an electrical device?[14] Electrostring's competitors infringed on the patent, but the owners did not have the money to litigate the infringements. Beauchamp was ultimately deprived of economic benefit for his invention because his competitors rapidly improved on it making his specific patent obsolete.[16] Electrostring's most successful product was the Hawaiian guitar (lap steel) A22 "Frying Pan", the first electrified instrument of any kind [1]— made with a metal body, smaller than a traditional Spanish guitar, to be played on the musician's lap. Two additional breakthroughs emerged: One, the guitar amplifier, which had to be purchased in order to use the invention;[17] and two, perhaps unrealized at the time, that electrified guitars no longer had to have the traditional guitar shape—this profoundly influenced electric guitar designs forever forward.[12]

Lap steel

Rickenbacker lap steel guitar, Electro B6, with Beauchamp horseshoe pickup, late 1930s

The first lap steels had a smaller body, but still retained a guitar-like shape. Instrument makers rapidly began making them into a rectangular block of wood with an electric pickup, the precursor of the pedal steel. According to music writer Michael Ross, the first electrified stringed instrument on a commercial recording was a western swing tune by Bob Dunn in 1935.[1][18] He recorded with Milton Brown and his Musical Brownies.[1] Brown has been called "The father of western swing" [19]

Lap steel becomes console steel

The next problem to be dealt with was the need to play in different keys and with different chords on the steel guitar.[20] The only way to accomplish this at the time was the addition of a duplicate neck and strings on the same instrument, tuned differently.

Rickenbacker Console 758 tripleneck steel - 2011 TSGA Jamboree

Players continued to add more necks, eventually getting up to four. This meant a bigger and heavier instrument, now called a "console" which necessitated putting it on a stand or legs rather than the performer's lap. Noel Boggs, a lap steel player with Bob Wills, received the first steel guitar made by instrument maker Leo Fender in 1956. Fender relied on prominent performers to field test his instruments.[21] Boggs was one of the first players to switch to a different neck during a solo.[1]Leon McAuliffe, composer of "Steel Guitar Rag" also played with Bob Wills, and used a multi-neck steel guitar. When Wills said his well-known tag line, "Take it away, Leon", he was referring to McAuliffe.[1] A Fender triple-neck console steel was heard in a number one hit song in the 1960s, "Sleep Walk", a steel guitar instrumental by Santo and Johnny, the Farina Brothers.

Console steel becomes pedal steel

The expense of building multiple necks on the same instrument made them unaffordable for most players, and a more sophisticated solution was needed. At this point, the goal was simply to create a pedal that would change the pitch of all the strings at once to emulate a second neck.[22] In 1939, a guitar called the "Electradaire" featured a pedal controlling a solenoid, triggering an electrical apparatus to change the tension on the strings.[23] This was not successful. That same year, Alvino Rey worked with a machinist to design pedals to change the pitch of strings but was without success. The Harlan Brothers of Indianapolis created the "Multi-Kord" with a universal pedal that could fairly easily be configured to adjust the pitch of any or all strings, but was extremely hard to push when tensioning all strings at once.[23]Gibson Guitar Company introduced the "Electraharp" in 1940, which featured pedals radially oriented from a single axis at the instrument's left rear leg.

Bigsby steel

The most successful pedal system from the various contenders was designed about 1948 by Paul Bigsby, a motorcycle shop foreman and racer who also invented the commercially successful Spanish guitar vibrato tailpiece.[24] Bigsby put pedals on a rack between the two front legs of the steel guitar. The pedals operated a mechanical linkage to apply tension to raise the pitch of the strings.[25] This is not as straightforward as it might sound. The pedal mechanism itself has to have its own tuning system. As an example, assume the guitar is tuned perfectly using the familiar tuning pegs easily visible on the guitar. Then assume that the player pushes a pedal and the result is out of tune, but when he releases the pedal, it is in tune again. Underneath the guitar, a system of levers, springs and long rods is seen. At the player's right, on the end of the instrument, is an opening that exposes the ends of the rods, each representing a string. The player fits a small hex wrench that looks like a radio knob onto the rod controlling the out-of-tune note. While holding the pedal down, he turns the knob either direction to fine-tune the pedal in a process completely independent of the original tuning.[24] Bigsby built guitars incorporating his design for the foremost steel players of the day, including Speedy West, Noel Boggs, and Bud Isaacs, but Bigsby was a one-man operation working out of his garage at age 56, and not capable of keeping up with demand.[23] One of Bigsby's first guitars was used on "Candy Kisses" in 1949 by Eddie Kirk.[26] The second model Bigsby made went to Speedy West, who used it extensively.[24]

Bud Isaacs: the birth of a new sound in country music

In 1953, Bud Isaacs attached a pedal to a guitar neck to change only two strings, and was the first to push the pedal while notes were still sounding. Other steel players strictly avoided doing this, because it was considered "un-Hawaiian".[1]

When Isaacs first used the setup on the 1956 recording of Webb Pierce's hit "Slowly", he pushed the pedal while playing a chord, so notes could be heard bending up from below into the existing chord to harmonize with the other strings, creating a stunning effect which had not been possible with the steel bar. Of this recording of "Slowly", steel guitar virtuoso Lloyd Green said, "This fellow, Bud Isaacs, had thrown a new tool into musical thinking about the steel with the advent of this record that still reverberates to this day."[24] It was the birth of the future sound of country music and caused a virtual revolution among steel players who wanted to duplicate it.[20][24]

Also in the 1950s, steel guitar hall-of-famer Zane Beck[27] added knee levers to the pedal steel guitar. The player can move each knee either right, left or up (depending on the model) triggering different pitch changes. The levers function basically the same as foot pedals, and may be used alone, in combination with the other knee, or more commonly, in combination with one or two foot pedals.[28] They were first added to Ray Noren's console steel.[24] Initially, the knee levers just lowered the pitch, but in later years with refinements, could raise or lower pitch.

Buddy Emmons' contributions to pedal steel

When "Slowly" was released, Bigsby was in the process of building a guitar for steel virtuoso Buddy Emmons. Emmons heard Isaacs' performance on the song, and told Bigsby to make his guitar setup to split the function of Isaacs' single pedal into two pedals, each controlling a different string. This gave the advantages of making chords without having to slant or move the bar, e.g., minors and suspended chords. Jimmy Day, another prominent steel player of the day, did the same thing, but reversed which strings were affected by the two pedals. This prompted future manufacturers to ask customers if they wanted a "Day" or an "Emmons" setup. In 1957, Emmons partnered with guitarist/machinist Harold "Shot" Jackson to form the Sho-Bud company, the first company devoted solely to pedal steel guitar manufacture.

Emmons made other innovations to the steel guitar, adding two additional strings (known as "chromatics") and a third pedal, changes which have been adopted as standard in the modern-day E9 instrument.[29][30] The additional strings allow the player to play a major scale without moving the bar.[31] He also developed and patented a mechanism to raise and lower the pitch of a string on a steel guitar and return to the original pitch without going out of tune.[32] The Sho-Bud instruments of the day had all the latest features: 10 strings, the third pedal, and the knee levers.

The modern pedal steel

Play media

Play mediaA song played on a pedal steel guitar.

The pedal steel continues to be an instrument in transition.[24] In the United States, as of 2017, the E9 neck is more common, but most pedal steels still have two necks. The C6 is typically used for Hawaiian and western swing music and the E9 neck is more often used for country music.[33] The different necks have distincty different voicings. The C6 has a wider pitch range than the E9, mostly on the lower notes.[34]

Certain players prefer different setups regarding which function the pedals and levers perform, and which string tuning is preferred. In the early 1970s, musician Tom Bradshaw coined the term "copedent" (pronounced co-PEE-dent), an acronym for "Chord-Pedal-Arrangement". Often represented in table form, it is a way of specifying the instrument's tuning, pedal and lever setup, string gauges and string windings.

There are proponents of a "universal tuning" to combine the two most popular modern tunings (E9 and C6) into a single 12 or 14-string neck that encompasses some features of each.[24] It was developed by Maurice Anderson and later modified by Larry Bell. By lowering the C6 tuning a half-step to make it a B6, many commonalities with the E9 tuning are achieved on the same neck and it is called the E9/B6 tuning.[35]

Pedal steel in other genres

The pedal steel most commonly associated with American country music and Hawaiian music but is heard in jazz, sacred music, popular music, nu jazz, Indian music, and African music.[36][1]

In the United States in the 1930s, during the steel guitar's wave of popularity, the instrument was introduced into the House of God, a branch of an African-American Pentecostal denomination, based primarily in Nashville and Indianapolis. The sound bore no resemblance to typical American country music.[37] The pedal steel was embraced by the congregation and often took the place of an organ. This musical genre, known as "Sacred Steel" was largely unknown until, in the 1980s, a minister's son named Robert Randolph, took up the instrument as a teenager, and has popularized it and received critical acclaim as a musician.[38] Neil Strauss, writing in the New York Times, called Randolph "one of the most original and talented pedal steel guitarists of his generation.[39]

The pedal steel guitar became a signature component of Nigerian Juju music in the late 1970s.[40] Nigerian bandleader King Sunny Adé features steel guitar in his 17 piece band, which, says New York Times reviewer Jon Pareles, introduces "a twang or two from American blues and country" [41] Norwegian jazz trumpeter Nils Petter Molvaer, considered a pioneer of Future jazz (a fusion of jazz and electronic music), released the album Switch, which features the pedal steel guitar.[42]

The steel guitar's popularity in India began with a Hawaiian immigrant who settled in Calcutta in the 1940s named Tau Moe (pronounced mo-ay). Moe taught Hawaiian guitar style and made steel guitars, and is believed to have been a force in popularizing the instrument in India.[43] By the 1960s, the steel had become a common instrument in Indian popular music—later included in film sound tracks. Indian musicians generally have not used pedals —they have played the lap steel while sitting on the floor and modified the instrument by using, for example, three melody strings (played with steel bar and finger picks), four plucked drone strings, and 12 sympathetic strings to buzz like a sitar.[44] Performing in this manner, the Indian musician Brij Bhushan Kabra adapted the steel guitar to play ragas, traditional Indian compositions and is called the father of the genre of Hindustani Slide Guitar.[43]

See also

- Console steel guitar

- Electric guitar

- Frying pan (guitar)

- Pedal Steel Guitar Association

- Resonator guitar

- Slack-key guitar

- Slide guitar

- Steel guitar

References

^ abcdefghijkl Ross, Michael (February 17, 2015). "Pedal to the Metal: A Short History of the Pedal Steel Guitar". Premier Guitar Magazine. Retrieved September 1, 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ ab Fox, Margalit (March 5, 2008). "Ray Kane, Master of Slack-Key Guitar, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

^ "History of the Hawaiian Steel Guitar". Hawaiian Steel Guitar Association. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

^ ab Duchossoir, A.R. (2009). Gibson electric steel guitars : 1935-1967. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4234-5702-2. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

^ Ruymar, Lorene (1996). "The Hawaiian Steel Guitar and It's Great Hawaiian Musicians". Centerstream Publications. p. 31. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

^ "Hawaiian Music to be Feature of Big Chautauqua Program". The Colville Examiner (No. 456). Colville, WA. July 22, 1916. p. 6. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

^ "Polynesian Cultural Center Unveils Statue of Joseph Keku, Inventor of the Hawaiian Steel Guitar". polynesia.com. Polynesian Cultural Center. 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

^ "Bird of Paradise Brought Hawaiian Music Fad East". The Washington Herald (No. 4188). April 14, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

^ Ruymar, Lorene (1996). "The Hawaiian Steel Guitar and Its Great Hawaiian Musicians/Hawaii Calls". books.google.com. Centerstream. p. 46. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

^ Betts, Stephen L. (July 30, 2015). "Steel Guitar Great Buddy Emmons Dies". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media. ISSN 0035-791X. OCLC 693532152. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

^ ab Herzhaft, Gérard (1996). Encyclopedia of the Blues (5. Dr. ed.). Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press. pp. 334–335. ISBN 1-55728-252-8.

^ ab "Early History of the Steel Guitar". steelguitaracademy.com. Steel Guitar Academy. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

^ Tom Noe. "Herman Weissenborn". Weissenborn → History. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

^ abcdefgh "The Earliest Days of the Electric Guitar". rickenbacker.com. Rickenbacker International. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

^ Drozdowski, Ted (December 18, 2012). "How Resonator Guitars Work and Sound So Cool". gibson.com. Gibson Brands. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

^ abc "First-ever electric guitar patent awarded to the Electro String Corporation". history.com. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

^ Teagle, John (September 1997). "Antique Guitar Amps 1928-1934". Vintage Guitar Magazine. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

^ Foley, Hugh W., Jr. "Dunn, Robert Lee (1908-1971)". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

^ Ginell, Cary (1994). Milton Brown and the Founding of Western Swing. Urbana, IL: Univ. of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02041-3.

^ ab Brenner, Patrick. "Early History of the Steel Guitar". steelguitaramerica.com. Patrick Brenner. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

^ Meeker, Ward (November 2014). "Boggs' Quad". Vintage Guitar Magazine. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

^ Anderson, Maurice (2000). "Pedal Steel Guitar, Back and To the Future!". The Pedal Steel Pages. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

^ abc Seymour, Bobbe (April 30, 2012). "Early History of the Pedal Steel Guitar". pedalsteelmusic.com. Steel Guitar Nashville. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

^ abcdefgh Winston, Winnie; Keith, Bill (1975). Pedal steel guitar. New York: Oak Publications. p. 116. ISBN 0-8256-0169-X.

^ Ross, Michael (November 17, 2011). "Forgotten Heroes: Paul Bigsby". Premier Guitar Magazine. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

^ "Eddie Kirk". allmusic.com. AllMusic, member of the RhythmOne group. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

^ Scott, Dewitt (1992). Back-Up Pedal Steel Guitar. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay. p. 41. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

^ "What's This Part? Knee Levers". steelguitar.com. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

^ Hurt, Edd (July 30, 2015). "Remembering Steel Guitar Innovator Buddy Emmons". Nashville Scene.

^ Miller, Tim Sterner (2017). "9. This Machine Plays Country Music: Invention, Innovation, and the Pedal Steel Guitar". In Stimeling, Travis D. The Oxford Handbook of Country Music. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190248178. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

^ Lee, Bobby (1996). "Basic Theory of the Standard E9th Tuning". The Pedal Steel Pages. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

^ Morris, Edward (July 30, 2015). "Steel Guitarist and Inventor Buddy Emmons Dead at 78". cmt.com. Viacom. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

^ Brenner, Patrick (2011). "The Open Tuning". steelguitaramerica. Steel Guitar Academy. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

^ McDuffie, John Groover (October 28, 2010). "The Steel Guitar Forum/C6 vs E9". bb.steelguitarforum.com. Steel Guitar Forum. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

^ Bell, Larry. "The E9/B6 Universal Tuning". larrybell.org. Larry Bell. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

^ Fischer, John (January 27, 2016). "Hawaiian Steel Guitar". tripsavy.com. Tripsavy. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

^ Stone, Robert L. (2010). Sacred steel : inside an African American steel guitar tradition. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0252-03554-8. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

^ Hansen, Liane; Wharton, Ned (August 5, 2001). "Heavenly 'Sacred Steel'". npr.org. NPR. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

^ Strauss, Neil (April 30, 2001). "Making Spirits Rock From Church to Clubland; A Gospel Pedal Steel Guitarist Dives Into Pop". The New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

^ "Juju and Pedal Steel". oldtimeparty.wordpress.com. WordPress. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

^ Pareles, Jon (May 15, 1987). "MUSIC: King Sunny Adé and Band from Nigeria". The New York Times. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

^ Molvaer, Nils Petter (March 11, 2014). "Nils Petter Molvaer releases album Switch". okeh-records.com. OKeh Records. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

^ ab Ellis, Andy (June 8, 2012). "The Secret World of Hindustani Slide". Premier Guitar Magazine. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

^ Bhatt, Vishwa Mohan (August 28, 2011). ""Raag Kirwani"(song)". youtube.com. YouTube. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

External links

- Universal tuning

- The British Steelies Society Forum

- Steel Guitar Forum - A discussion site for pedal steel, lap steel, and related musical instruments

- Steel Guitar Jazz - A website featuring pedal and nonpedal steel guitar in jazz music - run by Jim Cohen

- www.pedalsteel.co.uk - website run by Bob Adams

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Steel guitars. |