Social science

[dummy-text]

Social science

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

It has been suggested that Human science be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since June 2018. |

| Part of a series on | ||||||||

| Science | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

Social science is a category of academic disciplines, concerned with society and the relationships among individuals within a society. Social science as a whole has many branches. These social sciences include, but are not limited to: anthropology, archaeology, communication studies, economics, history, human geography, jurisprudence, linguistics, political science, psychology, public health, and sociology. The term is also sometimes used to refer specifically to the field of sociology, the original "science of society", established in the 19th century. For a more detailed list of sub-disciplines within the social sciences see: Outline of social science.

Positivist social scientists use methods resembling those of the natural sciences as tools for understanding society, and so define science in its stricter modern sense. Interpretivist social scientists, by contrast, may use social critique or symbolic interpretation rather than constructing empirically falsifiable theories, and thus treat science in its broader sense. In modern academic practice, researchers are often eclectic, using multiple methodologies (for instance, by combining both quantitative and qualitative research). The term "social research" has also acquired a degree of autonomy as practitioners from various disciplines share in its aims and methods.

Contents

1 History

2 Branches

2.1 Anthropology

2.2 Communication studies

2.3 Economics

2.4 Education

2.5 Geography

2.6 History

2.7 Law

2.8 Linguistics

2.9 Political science

2.10 Psychology

2.11 Sociology

3 Additional fields of study

4 Methodology

4.1 Social research

4.2 Theory

5 Education and degrees

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 Bibliography

9.1 20th and 21st centuries sources

9.2 19th century sources

9.3 General sources

9.4 Academic resources

9.5 Opponents and critics

10 External links

History[edit]

The history of the social sciences begins in the Age of Enlightenment after 1650,[1] which saw a revolution within natural philosophy, changing the basic framework by which individuals understood what was "scientific". Social sciences came forth from the moral philosophy of the time and were influenced by the Age of Revolutions, such as the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution.[2] The social sciences developed from the sciences (experimental and applied), or the systematic knowledge-bases or prescriptive practices, relating to the social improvement of a group of interacting entities.[3][4]

The beginnings of the social sciences in the 18th century are reflected in the grand encyclopedia of Diderot, with articles from Jean-Jacques Rousseau and other pioneers. The growth of the social sciences is also reflected in other specialized encyclopedias. The modern period saw "social science" first used as a distinct conceptual field.[5] Social science was influenced by positivism,[2] focusing on knowledge based on actual positive sense experience and avoiding the negative; metaphysical speculation was avoided. Auguste Comte used the term "science sociale" to describe the field, taken from the ideas of Charles Fourier; Comte also referred to the field as social physics.[2][6]

Following this period, there were five paths of development that sprang forth in the social sciences, influenced by Comte on other fields.[2] One route that was taken was the rise of social research. Large statistical surveys were undertaken in various parts of the United States and Europe. Another route undertaken was initiated by Émile Durkheim, studying "social facts", and Vilfredo Pareto, opening metatheoretical ideas and individual theories. A third means developed, arising from the methodological dichotomy present, in which social phenomena were identified with and understood; this was championed by figures such as Max Weber. The fourth route taken, based in economics, was developed and furthered economic knowledge as a hard science. The last path was the correlation of knowledge and social values; the antipositivism and verstehen sociology of Max Weber firmly demanded this distinction. In this route, theory (description) and prescription were non-overlapping formal discussions of a subject.

Around the start of the 20th century, Enlightenment philosophy was challenged in various quarters. After the use of classical theories since the end of the scientific revolution, various fields substituted mathematics studies for experimental studies and examining equations to build a theoretical structure. The development of social science subfields became very quantitative in methodology. The interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary nature of scientific inquiry into human behaviour, social and environmental factors affecting it, made many of the natural sciences interested in some aspects of social science methodology.[7] Examples of boundary blurring include emerging disciplines like social research of medicine, sociobiology, neuropsychology, bioeconomics and the history and sociology of science. Increasingly, quantitative research and qualitative methods are being integrated in the study of human action and its implications and consequences. In the first half of the 20th century, statistics became a free-standing discipline of applied mathematics. Statistical methods were used confidently.

In the contemporary period, Karl Popper and Talcott Parsons influenced the furtherance of the social sciences.[2] Researchers continue to search for a unified consensus on what methodology might have the power and refinement to connect a proposed "grand theory" with the various midrange theories that, with considerable success, continue to provide usable frameworks for massive, growing data banks; for more, see consilience. The social sciences will for the foreseeable future be composed of different zones in the research of, and sometime distinct in approach toward, the field.[2]

The term "social science" may refer either to the specific sciences of society established by thinkers such as Comte, Durkheim, Marx, and Weber, or more generally to all disciplines outside of "noble science" and arts. By the late 19th century, the academic social sciences were constituted of five fields: jurisprudence and amendment of the law, education, health, economy and trade, and art.[3]

Around the start of the 21st century, the expanding domain of economics in the social sciences has been described as economic imperialism.[8]

Branches[edit]

|

The following are problem areas and discipline branches within the social sciences.[2]

|

The social science disciplines are branches of knowledge taught and researched at the college or university level. Social science disciplines are defined and recognized by the academic journals in which research is published, and the learned social science societies and academic departments or faculties to which their practitioners belong. Social science fields of study usually have several sub-disciplines or branches, and the distinguishing lines between these are often both arbitrary and ambiguous.

Anthropology[edit]

Anthropology is the holistic "science of man", a science of the totality of human existence. The discipline deals with the integration of different aspects of the social sciences, humanities, and human biology. In the twentieth century, academic disciplines have often been institutionally divided into three broad domains. The natural sciences seek to derive general laws through reproducible and verifiable experiments. The humanities generally study local traditions, through their history, literature, music, and arts, with an emphasis on understanding particular individuals, events, or eras. The social sciences have generally attempted to develop scientific methods to understand social phenomena in a generalizable way, though usually with methods distinct from those of the natural sciences.

The anthropological social sciences often develop nuanced descriptions rather than the general laws derived in physics or chemistry, or they may explain individual cases through more general principles, as in many fields of psychology. Anthropology (like some fields of history) does not easily fit into one of these categories, and different branches of anthropology draw on one or more of these domains.[9] Within the United States, anthropology is divided into four sub-fields: archaeology, physical or biological anthropology, anthropological linguistics, and cultural anthropology. It is an area that is offered at most undergraduate institutions. The word anthropos (ἄνθρωπος) in Ancient Greek means "human being" or "person". Eric Wolf described sociocultural anthropology as "the most scientific of the humanities, and the most humanistic of the sciences."

The goal of anthropology is to provide a holistic account of humans and human nature. This means that, though anthropologists generally specialize in only one sub-field, they always keep in mind the biological, linguistic, historic and cultural aspects of any problem. Since anthropology arose as a science in Western societies that were complex and industrial, a major trend within anthropology has been a methodological drive to study peoples in societies with more simple social organization, sometimes called "primitive" in anthropological literature, but without any connotation of "inferior".[10] Today, anthropologists use terms such as "less complex" societies or refer to specific modes of subsistence or production, such as "pastoralist" or "forager" or "horticulturalist" to refer to humans living in non-industrial, non-Western cultures, such people or folk (ethnos) remaining of great interest within anthropology.

The quest for holism leads most anthropologists to study a people in detail, using biogenetic, archaeological, and linguistic data alongside direct observation of contemporary customs.[11] In the 1990s and 2000s, calls for clarification of what constitutes a culture, of how an observer knows where his or her own culture ends and another begins, and other crucial topics in writing anthropology were heard. It is possible to view all human cultures as part of one large, evolving global culture. These dynamic relationships, between what can be observed on the ground, as opposed to what can be observed by compiling many local observations remain fundamental in any kind of anthropology, whether cultural, biological, linguistic or archaeological.[12]

Communication studies[edit]

Communication studies deals with processes of human communication, commonly defined as the sharing of symbols to create meaning. The discipline encompasses a range of topics, from face-to-face conversation to mass media outlets such as television broadcasting. Communication studies also examines how messages are interpreted through the political, cultural, economic, and social dimensions of their contexts. Communication is institutionalized under many different names at different universities, including "communication", "communication studies", "speech communication", "rhetorical studies", "communication science", "media studies", "communication arts", "mass communication", "media ecology", and "communication and media science".

Communication studies integrates aspects of both social sciences and the humanities. As a social science, the discipline often overlaps with sociology, psychology, anthropology, biology, political science, economics, and public policy, among others. From a humanities perspective, communication is concerned with rhetoric and persuasion (traditional graduate programs in communication studies trace their history to the rhetoricians of Ancient Greece). The field applies to outside disciplines as well, including engineering, architecture, mathematics, and information science.

Economics[edit]

Economics is a social science that seeks to analyze and describe the production, distribution, and consumption of wealth.[13] The word "economics" is from the Ancient Greek οἶκος oikos, "family, household, estate", and νόμος nomos, "custom, law", and hence means "household management" or "management of the state". An economist is a person using economic concepts and data in the course of employment, or someone who has earned a degree in the subject. The classic brief definition of economics, set out by Lionel Robbins in 1932, is "the science which studies human behavior as a relation between scarce means having alternative uses". Without scarcity and alternative uses, there is no economic problem. Briefer yet is "the study of how people seek to satisfy needs and wants" and "the study of the financial aspects of human behavior".

Buyers bargain for good prices while sellers put forth their best front in Chichicastenango Market, Guatemala. |

Economics has two broad branches: microeconomics, where the unit of analysis is the individual agent, such as a household or firm, and macroeconomics, where the unit of analysis is an economy as a whole. Another division of the subject distinguishes positive economics, which seeks to predict and explain economic phenomena, from normative economics, which orders choices and actions by some criterion; such orderings necessarily involve subjective value judgments. Since the early part of the 20th century, economics has focused largely on measurable quantities, employing both theoretical models and empirical analysis. Quantitative models, however, can be traced as far back as the physiocratic school. Economic reasoning has been increasingly applied in recent decades to other social situations such as politics, law, psychology, history, religion, marriage and family life, and other social interactions.

This paradigm crucially assumes (1) that resources are scarce because they are not sufficient to satisfy all wants, and (2) that "economic value" is willingness to pay as revealed for instance by market (arms' length) transactions. Rival heterodox schools of thought, such as institutional economics, green economics, Marxist economics, and economic sociology, make other grounding assumptions. For example, Marxist economics assumes that economics primarily deals with the investigation of exchange value, of which human labour is the source.

The expanding domain of economics in the social sciences has been described as economic imperialism.[8][14]

Education[edit]

A depiction of world's oldest university, the University of Bologna, in Italy

Education encompasses teaching and learning specific skills, and also something less tangible but more profound: the imparting of knowledge, positive judgement and well-developed wisdom. Education has as one of its fundamental aspects the imparting of culture from generation to generation (see socialization). To educate means 'to draw out', from the Latin educare, or to facilitate the realization of an individual's potential and talents. It is an application of pedagogy, a body of theoretical and applied research relating to teaching and learning and draws on many disciplines such as psychology, philosophy, computer science, linguistics, neuroscience, sociology and anthropology.[15]

The education of an individual human begins at birth and continues throughout life. (Some believe that education begins even before birth, as evidenced by some parents' playing music or reading to the baby in the womb in the hope it will influence the child's development.) For some, the struggles and triumphs of daily life provide far more instruction than does formal schooling (thus Mark Twain's admonition to "never let school interfere with your education"). Family members may have a profound educational effect — often more profound than they realize — though family teaching may function very informally.

Geography[edit]

Map of the Earth

Geography as a discipline can be split broadly into two main sub fields: human geography and physical geography. The former focuses largely on the built environment and how space is created, viewed and managed by humans as well as the influence humans have on the space they occupy. This may involve cultural geography, transportation, health, military operations, and cities. The latter examines the natural environment and how the climate, vegetation and life, soil, oceans, water and landforms are produced and interact.[16]Physical geography examines phenomena related to the measurement of earth. As a result of the two subfields using different approaches a third field has emerged, which is environmental geography. Environmental geography combines physical and human geography and looks at the interactions between the environment and humans.[17] Other branches of geography include social geography, regional geography, and geomatics.

Geographers attempt to understand the Earth in terms of physical and spatial relationships. The first geographers focused on the science of mapmaking and finding ways to precisely project the surface of the earth. In this sense, geography bridges some gaps between the natural sciences and social sciences. Historical geography is often taught in a college in a unified Department of Geography.

Modern geography is an all-encompassing discipline, closely related to GISc, that seeks to understand humanity and its natural environment. The fields of urban planning, regional science, and planetology are closely related to geography. Practitioners of geography use many technologies and methods to collect data such as GIS, remote sensing, aerial photography, statistics, and global positioning systems (GPS).

History[edit]

History is the continuous, systematic narrative and research into past human events as interpreted through historiographical paradigms or theories.

History has a base in both the social sciences and the humanities. In the United States the National Endowment for the Humanities includes history in its definition of humanities (as it does for applied linguistics).[18] However, the National Research Council classifies history as a social science.[19] The historical method comprises the techniques and guidelines by which historians use primary sources and other evidence to research and then to write history. The Social Science History Association, formed in 1976, brings together scholars from numerous disciplines interested in social history.[20]

Law[edit]

A trial at a criminal court, the Old Bailey in London

The social science of law, jurisprudence, in common parlance, means a rule that (unlike a rule of ethics) is capable of enforcement through institutions.[21] However, many laws are based on norms accepted by a community and thus have an ethical foundation. The study of law crosses the boundaries between the social sciences and humanities, depending on one's view of research into its objectives and effects. Law is not always enforceable, especially in the international relations context. It has been defined as a "system of rules",[22] as an "interpretive concept"[23] to achieve justice, as an "authority"[24] to mediate people's interests, and even as "the command of a sovereign, backed by the threat of a sanction".[25] However one likes to think of law, it is a completely central social institution. Legal policy incorporates the practical manifestation of thinking from almost every social science and the humanities. Laws are politics, because politicians create them. Law is philosophy, because moral and ethical persuasions shape their ideas. Law tells many of history's stories, because statutes, case law and codifications build up over time. And law is economics, because any rule about contract, tort, property law, labour law, company law and many more can have long-lasting effects on the distribution of wealth. The noun law derives from the late Old English lagu, meaning something laid down or fixed[26] and the adjective legal comes from the Latin word lex.[27]

Linguistics[edit]

Ferdinand de Saussure, recognized as the father of modern linguistics

Linguistics investigates the cognitive and social aspects of human language. The field is divided into areas that focus on aspects of the linguistic signal, such as syntax (the study of the rules that govern the structure of sentences), semantics (the study of meaning), morphology (the study of the structure of words), phonetics (the study of speech sounds) and phonology (the study of the abstract sound system of a particular language); however, work in areas like evolutionary linguistics (the study of the origins and evolution of language) and psycholinguistics (the study of psychological factors in human language) cut across these divisions.

The overwhelming majority of modern research in linguistics takes a predominantly synchronic perspective (focusing on language at a particular point in time), and a great deal of it—partly owing to the influence of Noam Chomsky—aims at formulating theories of the cognitive processing of language. However, language does not exist in a vacuum, or only in the brain, and approaches like contact linguistics, creole studies, discourse analysis, social interactional linguistics, and sociolinguistics explore language in its social context. Sociolinguistics often makes use of traditional quantitative analysis and statistics in investigating the frequency of features, while some disciplines, like contact linguistics, focus on qualitative analysis. While certain areas of linguistics can thus be understood as clearly falling within the social sciences, other areas, like acoustic phonetics and neurolinguistics, draw on the natural sciences. Linguistics draws only secondarily on the humanities, which played a rather greater role in linguistic inquiry in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Ferdinand Saussure is considered the father of modern linguistics.

Political science[edit]

Aristotle asserted that man is a political animal in his Politics.[28]

Political science is an academic and research discipline that deals with the theory and practice of politics and the description and analysis of political systems and political behaviour. Fields and subfields of political science include political economy, political theory and philosophy, civics and comparative politics, theory of direct democracy, apolitical governance, participatory direct democracy, national systems, cross-national political analysis, political development, international relations, foreign policy, international law, politics, public administration, administrative behaviour, public law, judicial behaviour, and public policy. Political science also studies power in international relations and the theory of great powers and superpowers.

Political science is methodologically diverse, although recent years have witnessed an upsurge in the use of the scientific method,[29][page needed] that is, the proliferation of formal-deductive model building and quantitative hypothesis testing. Approaches to the discipline include rational choice, classical political philosophy, interpretivism, structuralism, and behaviouralism, realism, pluralism, and institutionalism. Political science, as one of the social sciences, uses methods and techniques that relate to the kinds of inquiries sought: primary sources such as historical documents, interviews, and official records, as well as secondary sources such as scholarly articles are used in building and testing theories. Empirical methods include survey research, statistical analysis or econometrics, case studies, experiments, and model building. Herbert Baxter Adams is credited with coining the phrase "political science" while teaching history at Johns Hopkins University.

Psychology[edit]

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt was the founder of experimental psychology.

Psychology is an academic and applied field involving the study of behaviour and mental processes. Psychology also refers to the application of such knowledge to various spheres of human activity, including problems of individuals' daily lives and the treatment of mental illness. The word psychology comes from the Ancient Greek ψυχή psyche ("soul", "mind") and logy ("study").

Psychology differs from anthropology, economics, political science, and sociology in seeking to capture explanatory generalizations about the mental function and overt behaviour of individuals, while the other disciplines focus on creating descriptive generalizations about the functioning of social groups or situation-specific human behaviour. In practice, however, there is quite a lot of cross-fertilization that takes place among the various fields. Psychology differs from biology and neuroscience in that it is primarily concerned with the interaction of mental processes and behaviour, and of the overall processes of a system, and not simply the biological or neural processes themselves, though the subfield of neuropsychology combines the study of the actual neural processes with the study of the mental effects they have subjectively produced.

Many people associate psychology with clinical psychology, which focuses on assessment and treatment of problems in living and psychopathology. In reality, psychology has myriad specialties including social psychology, developmental psychology, cognitive psychology, educational psychology, industrial-organizational psychology, mathematical psychology, neuropsychology, and quantitative analysis of behaviour.

Psychology is a very broad science that is rarely tackled as a whole, major block. Although some subfields encompass a natural science base and a social science application, others can be clearly distinguished as having little to do with the social sciences or having a lot to do with the social sciences. For example, biological psychology is considered a natural science with a social scientific application (as is clinical medicine), social and occupational psychology are, generally speaking, purely social sciences, whereas neuropsychology is a natural science that lacks application out of the scientific tradition entirely. In British universities, emphasis on what tenet of psychology a student has studied and/or concentrated is communicated through the degree conferred: B.Psy. indicates a balance between natural and social sciences, B.Sc. indicates a strong (or entire) scientific concentration, whereas a B.A. underlines a majority of social science credits. This is not always necessarily the case however, and in many UK institutions students studying the B.Psy, B.Sc, and B.A. follow the same curriculum as outlined by The British Psychological Society and have the same options of specialism open to them regardless of whether they choose a balance, a heavy science basis, or heavy social science basis to their degree. If they applied to read the B.A. for example, but specialized in heavily science-based modules, then they will still generally be awarded the B.A.

Sociology[edit]

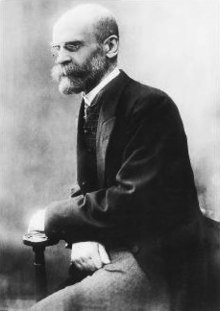

Émile Durkheim is considered one of the founding fathers of sociology.

Sociology is the systematic study of society, individuals' relationship to their societies, the consequences of difference, and other aspects of human social action.[30] The meaning of the word comes from the suffix "-logy", which means "study of", derived from Ancient Greek, and the stem "soci-", which is from the Latin word socius, meaning "companion", or society in general.

Auguste Comte (1798–1857) coined the term, Sociology, as a way to apply natural science principles and techniques to the social world in 1838.[31][32] Comte endeavoured to unify history, psychology and economics through the descriptive understanding of the social realm. He proposed that social ills could be remedied through sociological positivism, an epistemological approach outlined in The Course in Positive Philosophy [1830–1842] and A General View of Positivism (1844). Though Comte is generally regarded as the "Father of Sociology", the discipline was formally established by another French thinker, Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), who developed positivism as a foundation to practical social research. Durkheim set up the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux in 1895, publishing his Rules of the Sociological Method. In 1896, he established the journal L'Année Sociologique. Durkheim's seminal monograph, Suicide (1897), a case study of suicide rates among Catholic and Protestant populations, distinguished sociological analysis from psychology or philosophy.[33]

Karl Marx rejected Comte's positivism but nevertheless aimed to establish a science of society based on historical materialism, becoming recognized as a founding figure of sociology posthumously as the term gained broader meaning. Around the start of the 20th century, the first wave of German sociologists, including Max Weber and Georg Simmel, developed sociological antipositivism. The field may be broadly recognized as an amalgam of three modes of social thought in particular: Durkheimian positivism and structural functionalism; Marxist historical materialism and conflict theory; and Weberian antipositivism and verstehen analysis. American sociology broadly arose on a separate trajectory, with little Marxist influence, an emphasis on rigorous experimental methodology, and a closer association with pragmatism and social psychology. In the 1920s, the Chicago school developed symbolic interactionism. Meanwhile, in the 1930s, the Frankfurt School pioneered the idea of critical theory, an interdisciplinary form of Marxist sociology drawing upon thinkers as diverse as Sigmund Freud and Friedrich Nietzsche. Critical theory would take on something of a life of its own after World War II, influencing literary criticism and the Birmingham School establishment of cultural studies.

Sociology evolved as an academic response to the challenges of modernity, such as industrialization, urbanization, secularization, and a perceived process of enveloping rationalization.[34] The field generally concerns the social rules and processes that bind and separate people not only as individuals, but as members of associations, groups, communities and institutions, and includes the examination of the organization and development of human social life. The sociological field of interest ranges from the analysis of short contacts between anonymous individuals on the street to the study of global social processes. In the terms of sociologists Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, social scientists seek an understanding of the Social Construction of Reality. Most sociologists work in one or more subfields. One useful way to describe the discipline is as a cluster of sub-fields that examine different dimensions of society. For example, social stratification studies inequality and class structure; demography studies changes in a population size or type; criminology examines criminal behaviour and deviance; and political sociology studies the interaction between society and state.

Since its inception, sociological epistemologies, methods, and frames of enquiry, have significantly expanded and diverged.[35] Sociologists use a diversity of research methods, collect both quantitative and qualitative data, draw upon empirical techniques, and engage critical theory.[32] Common modern methods include case studies, historical research, interviewing, participant observation, social network analysis, survey research, statistical analysis, and model building, among other approaches. Since the late 1970s, many sociologists have tried to make the discipline useful for purposes beyond the academy. The results of sociological research aid educators, lawmakers, administrators, developers, and others interested in resolving social problems and formulating public policy, through subdisciplinary areas such as evaluation research, methodological assessment, and public sociology.

In the early 1970s, women sociologists began to question sociological paradigms and the invisibility of women in sociological studies, analysis, and courses.[36] In 1969, feminist sociologists challenged the discipline's androcentrism at the American Sociological Association's annual conference.[37] This led to the founding of the organization Sociologists for Women in Society, and, eventually, a new sociology journal, Gender & Society. Today, the sociology of gender is considered to be one of the most prominent sub-fields in the discipline.

New sociological sub-fields continue to appear — such as community studies, computational sociology, environmental sociology, network analysis, actor-network theory, gender studies, and a growing list, many of which are cross-disciplinary in nature.

Additional fields of study[edit]

Additional applied or interdisciplinary fields related to the social sciences include:

Archaeology is the science that studies human cultures through the recovery, documentation, analysis, and interpretation of material remains and environmental data, including architecture, artifacts, features, biofacts, and landscapes.

Area studies are interdisciplinary fields of research and scholarship pertaining to particular geographical, national/federal, or cultural regions.

Behavioural science is a term that encompasses all the disciplines that explore the activities of and interactions among organisms in the natural world.

Computational social science is an umbrella field encompassing computational approaches within the social sciences.

Demography is the statistical study of all human populations.

Development studies a multidisciplinary branch of social science that addresses issues of concern to developing countries.

Environmental social science is the broad, transdisciplinary study of interrelations between humans and the natural environment.

Environmental studies integrate social, humanistic, and natural science perspectives on the relation between humans and the natural environment.

Gender studies integrates several social and natural sciences to study gender identity, masculinity, femininity, transgender issues, and sexuality.

Information science is an interdisciplinary science primarily concerned with the collection, classification, manipulation, storage, retrieval and dissemination of information.

International studies covers both International relations (the study of foreign affairs and global issues among states within the international system) and International education (the comprehensive approach that intentionally prepares people to be active and engaged participants in an interconnected world).

Legal management is a social sciences discipline that is designed for students interested in the study of state and legal elements.

Library science is an interdisciplinary field that applies the practices, perspectives, and tools of management, information technology, education, and other areas to libraries; the collection, organization, preservation and dissemination of information resources; and the political economy of information.

Management consists of various levels of leadership and administration of an organization in all business and human organizations. It is the effective execution of getting people together to accomplish desired goals and objectives through adequate planning, executing and controlling activities.

Marketing the identification of human needs and wants, defines and measures their magnitude for demand and understanding the process of consumer buying behaviour to formulate products and services, pricing, promotion and distribution to satisfy these needs and wants through exchange processes and building long term relationships.

Political economy is the study of production, buying and selling, and their relations with law, custom, and government.

Public administration is one of the main branches of political science, and can be broadly described as the development, implementation and study of branches of government policy. The pursuit of the public good by enhancing civil society and social justice is the ultimate goal of the field. Though public administration has been historically referred to as government management,[38] it increasingly encompasses non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that also operate with a similar, primary dedication to the betterment of humanity.

Religious studies and Western esoteric studies incorporate and inform social-scientific research on phenomena broadly deemed religious. Religious studies, Western esoteric studies, and the social sciences developed in dialogue with one another.[39]

Methodology[edit]

Social research[edit]

The origin of the survey can be traced back at least early as the Domesday Book in 1086,[40][41] while some scholars pinpoint the origin of demography to 1663 with the publication of John Graunt's Natural and Political Observations upon the Bills of Mortality.[42] Social research began most intentionally, however, with the positivist philosophy of science in the 19th century.

In contemporary usage, "social research" is a relatively autonomous term, encompassing the work of practitioners from various disciplines that share in its aims and methods. Social scientists employ a range of methods in order to analyse a vast breadth of social phenomena; from census survey data derived from millions of individuals, to the in-depth analysis of a single agent's social experiences; from monitoring what is happening on contemporary streets, to the investigation of ancient historical documents. The methods originally rooted in classical sociology and statistical mathematics have formed the basis for research in other disciplines, such as political science, media studies, and marketing and market research.

Social research methods may be divided into two broad schools:

Quantitative designs approach social phenomena through quantifiable evidence, and often rely on statistical analysis of many cases (or across intentionally designed treatments in an experiment) to create valid and reliable general claims.

Qualitative designs emphasize understanding of social phenomena through direct observation, communication with participants, or analysis of texts, and may stress contextual and subjective accuracy over generality.

Social scientists will commonly combine quantitative and qualitative approaches as part of a multi-strategy design. Questionnaires, field-based data collection, archival database information and laboratory-based data collections are some of the measurement techniques used. It is noted the importance of measurement and analysis, focusing on the (difficult to achieve) goal of objective research or statistical hypothesis testing. A mathematical model uses mathematical language to describe a system. The process of developing a mathematical model is termed 'mathematical modelling' (also modeling). Eykhoff (1974) defined a mathematical model as 'a representation of the essential aspects of an existing system (or a system to be constructed) that presents knowledge of that system in usable form'.[43] Mathematical models can take many forms, including but not limited to dynamical systems, statistical models, differential equations, or game theoretic models.

These and other types of models can overlap, with a given model involving a variety of abstract structures. The system is a set of interacting or interdependent entities, real or abstract, forming an integrated whole. The concept of an integrated whole can also be stated in terms of a system embodying a set of relationships that are differentiated from relationships of the set to other elements, and from relationships between an element of the set and elements not a part of the relational regime. A dynamical system modeled as a mathematical formalization has a fixed "rule" that describes the time dependence of a point's position in its ambient space. Small changes in the state of the system correspond to small changes in the numbers. The evolution rule of the dynamical system is a fixed rule that describes what future states follow from the current state. The rule is deterministic: for a given time interval only one future state follows from the current state.

Social sciences are criticized for neglecting the moral element of human behavior. Economists tend to focus on self-interest. Clinical psychologists—on the effects of early socialization. Anthropologists tend to assume moral relativism. Sociologists often blame the System for immoral behavior. Socio-biologists tend to assume limited choice behavior. All this, critics hold, contrasts with the fact that life is a constant wrestle between people's moral commitments and urges that pull them to violate these commitments.[44]

Theory[edit]

Other social scientists emphasize the subjective nature of research. These writers share social theory perspectives that include various types of the following:

Critical theory is the examination and critique of society and culture, drawing from knowledge across social sciences and humanities disciplines.

Dialectical materialism is the philosophy of Karl Marx, which he formulated by taking the dialectic of Hegel and joining it to the materialism of Feuerbach.

Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into theoretical, or philosophical discourse; it aims to understand the nature of gender inequality.

Marxist theories, such as revolutionary theory and class theory, cover work in philosophy that is strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory or is written by Marxists.

Phronetic social science is a theory and methodology for doing social science focusing on ethics and political power, based on a contemporary interpretation of Aristotelian phronesis.

Post-colonial theory is a reaction to the cultural legacy of colonialism.

Postmodernism refers to a point of departure for works of literature, drama, architecture, cinema, and design, as well as in marketing and business and in the interpretation of history, law, culture and religion in the late 20th century.

Rational choice theory is a framework for understanding and often formally modeling social and economic behaviour.

Social constructionism considers how social phenomena develop in social contexts.

Structuralism is an approach to the human sciences that attempts to analyze a specific field (for instance, mythology) as a complex system of interrelated parts.

Structural functionalism is a sociological paradigm that addresses what social functions various elements of the social system perform in regard to the entire system.

Other fringe social scientists delve in alternative nature of research. These writers share social theory perspectives that include various types of the following:

Intellectual critical-ism describes a sentiment of critique towards, or evaluation of, intellectuals and intellectual pursuits.

Scientific criticalism is a position critical of science and the scientific method.

Education and degrees[edit]

Most universities offer degrees in social science fields.[45] The Bachelor of Social Science is a degree targeted at the social sciences in particular. It is often more flexible and in-depth than other degrees that include social science subjects.[a]

In the United States, a university may offer a student who studies a social sciences field a Bachelor of Arts degree, particularly if the field is within one of the traditional liberal arts such as history, or a BSc: Bachelor of Science degree such as those given by the London School of Economics, as the social sciences constitute one of the two main branches of science (the other being the natural sciences). In addition, some institutions have degrees for a particular social science, such as the Bachelor of Economics degree, though such specialized degrees are relatively rare in the United States.

See also[edit]

- General

- Outline of social science

- Society

- Culture

- Structure and agency

Humanities (human science)

- Methods

- Historical method

- Empiricism

- Representation theory

- Scientific method

- Statistical hypothesis testing

- Regression

- Correlation

- Terminology

- Participatory Action Research

- Areas

- Political sciences

- Natural sciences

- Behavioural sciences

- Geographic information science

- History

- History of science

- History of technology

- Lists

- Fields of science

- Outline of academic disciplines

- People

- Aristotle

- Plato

- Confucius

- Augustine

- Niccolò Machiavelli

- Émile Durkheim

- Max Weber

- Karl Marx

- Friedrich Engels

- Herbert Spencer

- Sir John Lubbock

- Alfred Schutz

- Adam Smith

- David Ricardo

- Jean-Baptiste Say

- John Maynard Keynes

- Robert Lucas

- Milton Friedman

- Sigmund Freud

- Jean Piaget

- Noam Chomsky

- B.F. Skinner

- John Stuart Mill

- Thomas Hobbes

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Montesquieu

- John Locke

- David Hume

- Auguste Comte

- Steven Pinker

- John Rawls

- Other

- Behaviour

Ethology and Ethnology- Game theory

- Gulbenkian commission

- Labelling

Periodic table of human sciences (Tinbergen's four questions)- Social action

- Philosophy of social sciences

Notes[edit]

^ A Bachelor of Social Science degree can be earned at the University of Adelaide, University of Waikato (Hamilton, New Zealand), University of Sydney, University of New South Wales, University of Hong Kong, University of Manchester, Lincoln University, New Zealand, National University of Malaysia and University of Queensland.

References[edit]

^ Kuper, Adam (1996). The Social Science Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0415108294..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abcdefg Kuper, A., and Kuper, J. (1985). The Social Science Encyclopaedia.

^ ab Social sciences, Columbian Cyclopedia. (1897). Buffalo: Garretson, Cox & Company. p. 227.

^ Peck, H.T., Peabody, S.H., and Richardson, C.F. (1897). The International Cyclopedia, A Compendium of Human Knowledge. Rev. with large additions. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company.

^ William Thompson (1775–1833) (1824). An Inquiry into the Principles of the Distribution of Wealth Most Conducive to Human Happiness; applied to the Newly Proposed System of Voluntary Equality of Wealth.

^ According to Comte, the social physics field was similar to that of natural sciences.

^ Vessuri, H. (2002). "Ethical Challenges for the Social Sciences on the Threshold of the 21st Century". Current Sociology. 50: 135–50. doi:10.1177/0011392102050001010.

^ ab Lazear, E.P. (2000). "Economic Imperialism". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 115: 99–146. doi:10.1162/003355300554683.

^ Wallerstein, I. (2003). "Anthropology, Sociology, and Other Dubious Disciplines". Current Anthropology. 44 (4): 453–65. doi:10.1086/375868.

^ Lowie, Robert (1924). Primitive Religion. Routledge and Sons.; Tylor, Edward (1920). Primitive Culture. New York:: J.P. Putnam's Sons. Originally published 1871.

^ Nanda, Serena and Richard Warms. Culture Counts. Wadsworth. 2008. Chapter One

^ Rosaldo, Renato. Culture and Truth: The remaking of social analysis. Beacon Press. 1993; Inda, John Xavier and Renato Rosaldo. The Anthropology of Globalization. Wiley-Blackwell. 2007

^ economics – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

^ Becker, Gary S. (1976). The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. Links to arrow-page viewable chapter. University of Chicago Press.

^ An overview of education

^ "What is geography?". AAG Career Guide: Jobs in Geography and Related Geographical Sciences. Association of American Geographers. Archived from the original on October 6, 2006. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

^ Hayes-Bohanan, James. "What is Environmental Geography, Anyway?". Retrieved October 9, 2006.

^ "About NEH". National Endowment for the Humanities.

^ Research-Doctorate Programs in the United States: Continuity and Change

^ See the SSHA website

^ Robertson, Geoffrey (2006). Crimes Against Humanity. Penguin. p. 90. ISBN 978-0141024639.

^ Hart, H.L.A. (1961). The Concept of Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198761228.

^ Dworkin, Ronald (1986). Law's Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674518360.

^ Raz, Joseph (1979). The Authority of Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199562688.

^ Austin, John (1831). The Providence of Jurisprudence Determined.

^ see Etymonline Dictionary

^ see Merriam-Webster's Dictionary

^ Ebenstein, Alan (2002). Introduction to Political Thinkers. Boston, Massachusetts: Wadsworth.

^ Hindmoor, Andrew (2006-08-08). Rational Choice. ISBN 978-1403934222.

^ Witt, Jon (2018). SOC 218. McGraw-Hill. p. 2. ISBN 978-1259702723.

^ A Dictionary of Sociology, Article: Comte, Auguste

^ ab Witt, Jon (2018). SOC 2018. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1259702723.

^ Gianfranco Poggi (2000). Durkheim. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chapter 1.

^ Habermas, Jürgen, The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Modernity's Consciousness of Time, Polity Press (1990), paperback,

ISBN 0745608302, p. 2.

^ Giddens, Anthony, Duneier, Mitchell, Applebaum, Richard. 2007. Introduction to Sociology. Sixth Edition. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. Chapter 1.

^ Lorber, Judith (1994). Paradoxes of Gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300064971.

^ Laube, Heather; Hess, Bess B. (2001). "The Founding of SWS". Sociologists for Women in Society. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

^ Zaki Badawi, A (2002). Dictionary of the Social Sciences – Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195123715.001.0001. ISBN 978-0195123715.

^ Josephson-Storm, Jason (2017). The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 101–14. ISBN 978-0226403366.

^ A.H. Halsey (2004), A history of sociology in Britain: science, literature, and society, p. 34

^ Geoffrey Duncan Mitchell (1970), A new dictionary of sociology, p. 201

^ Willcox, Walter (1938) The Founder of Statistics.

^ Eykhoff, Pieter System Identification: Parameter and State Estimation, Wiley & Sons, (1974).

ISBN 0471249807

^ Amitai Etzioni. 2017. "The Moral Wrestler: Ignored by Maslow." Society, Volume 54, Issue 6, pp. 512–19

^ Peterson's (Firm : 2006– ). (2007). Peterson's graduate programs in the humanities, arts, & social sciences, 2007. Lawrenceville, New Jersey: Peterson's.

Bibliography[edit]

20th and 21st centuries sources[edit]

Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes (2001). International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Amsterdam: Elsevier.- Byrne, D.S. (1998). Complexity theory and the social sciences: an introduction. Routledge.

ISBN 0415162963 - Kuper, A., and Kuper, J. (1985). The Social Science Encyclopedia. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. (ed., a limited preview of the 1996 version is available)

- Lave, C.A., and March, J.G. (1993). An introduction to models in the social sciences. Lanham, Md: University Press of America.

- Perry, John and Erna Perry. Contemporary Society: An Introduction to Social Science (12th Edition, 2008), college textbook

- Potter, D. (1988). Society and the social sciences: An introduction. London: Routledge [u.a.].

- David L. Sills and Robert K. Merton (1968). International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences.

- Seligman, Edwin R.A. and Alvin Johnson (1934). Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. (13 vol.)

- Ward, L.F. (1924). Dynamic sociology, or applied social science: As based upon statical sociology and the less complex sciences. New York: D. Appleton.

- Leavitt, F.M., and Brown, E. (1920). Elementary social science. New York: Macmillan.

- Bogardus, E.S. (1913). Introduction to the social sciences: A textbook outline. Los Angeles: Ralston Press.

- Small, A.W. (1910). The meaning of social science. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

19th century sources[edit]

- Andrews, S.P. (1888). The science of society. Boston, Mass: Sarah E. Holmes.

- Denslow, V.B. (1882). Modern thinkers principally upon social science: What they think, and why. Chicago: Belford, Clarke & Co.

Harris, William Torrey (1879). Method of Study in Social Science: A Lecture Delivered Before the St. Louis Social Science Association, March 4, 1879. St. Louis: G.I. Jones and Co, 1879.- Hamilton, R.S. (1873). Present status of social science. A review, historical and critical, of the progress of thought in social philosophy. New York: H.L. Hinton.

- Carey, H.C. (1867). Principles of social science. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. [etc.]. Volume I, Volume II, Volume III.

- Calvert, G.H. (1856). Introduction to social science: A discourse in three parts. New York: Redfield.

General sources[edit]

- Backhouse, Roger E., and Philippe Fontaine, eds. A historiography of the modern social sciences (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Backhouse, Roger E.; Fontaine, eds., Philippe, eds. (2010). The History of the Social Sciences Since 1945. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: Extra text: editors list (link) ; covers the conceptual, institutional, and wider histories of economics, political science, sociology, social anthropology, psychology, and human geography.

Delanty, G. (1997). Social science: Beyond constructivism and realism. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Hargittai, E. (2009). Research Confidential: Solutions to Problems Most Social Scientists Pretend They Never Have. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472026531.

ISBN 978-0472050260, 978-0472070268

Hunt, E.F.; Colander, D.C. (2008). Social science: An introduction to the study of society. Boston: Peason/Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0205524068.

Carey, H.C.; McKean, K. (1883). Manual of social science; Being a condensation of the Principles of social science. Philadelphia: Baird.

Galavotti, M.C. (2003). Observation and experiment in the natural and social sciences. Boston studies in the philosophy of science. 232. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. ISBN 978-1402012518.

Gorton, W.A. (2006). Karl Popper and the social sciences. SUNY series in the philosophy of the social sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Harris, F.R. (1973). Social science and national policy. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books. ISBN 978-1412834452. distributed by Dutton

Krimerman, L.I. (1969). The nature and scope of social science: A critical anthology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Rule, J.B. (1997). Theory and progress in social science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shionoya, Y. (1997). Schumpeter and the idea of social science: A metatheoretical study. Historical perspectives on modern economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Singleton, Royce, A.; Straits, Bruce C. (1988). Approaches to Social Research. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195147940. Archived from the original on March 3, 2007.

Thomas, D. (1979). Naturalism and social science: a post-empiricist philosophy of social science. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0521296601.

Trigg, R. (2001). Understanding social science: A philosophical introduction to the social sciences. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishers.

Weber, M. (1906) [1904]. The Relations of the Rural Community to Other Branches of Social Science, Congress of Arts and Science: Universal Exposition. St. Louis: Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

Academic resources[edit]

The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,

ISSN 1552-3349 (electronic)

ISSN 0002-7162 (paper), SAGE Publications- Efferson, C. and Richerson, P.J.(In press). A prolegomenon to nonlinear empiricism in the human behavioral sciences. Philosophy and Biology. Full text

Opponents and critics[edit]

George H. Smith (2014). Intellectuals and Libertarianism: Thomas Sowell and Robert Nisbet- Phil Hutchinson, Rupert Read and Wes Sharrock (2008). There's No Such Thing as a Social Science.

ISBN 978-0754647768 - Sabia, D.R., and Wallulis, J. (1983). Changing social science: Critical theory and other critical perspectives. Albany: State University of New York Press.

External links[edit]

Institute for Comparative Research in Human and Social Sciences (ICR) (JAPAN)- Centre for Social Work Research

- Family Therapy and Systemic Research Centre

- International Conference on Social Sciences

- International Social Science Council

- Introduction to Hutchinson et al., There's No Such Thing as a Social Science

- Intute: Social Sciences (UK)

- Social Science Research Society

- Social Science Virtual Library

- Social Science Virtual Library: Canaktanweb (Turkish)

- Social Sciences And Humanities

- UC Berkeley Experimental Social Science Laboratory

The Dialectic of Social Science by Paul A. Baran- American Academy Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences

Social Phenomena by Teng Wang

Categories:

- Social sciences

- Academic disciplines

- Scientific disciplines

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function()mw.config.set("wgPageParseReport":"limitreport":"cputime":"1.264","walltime":"1.653","ppvisitednodes":"value":5297,"limit":1000000,"ppgeneratednodes":"value":0,"limit":1500000,"postexpandincludesize":"value":189748,"limit":2097152,"templateargumentsize":"value":7909,"limit":2097152,"expansiondepth":"value":13,"limit":40,"expensivefunctioncount":"value":11,"limit":500,"unstrip-depth":"value":1,"limit":20,"unstrip-size":"value":99774,"limit":5000000,"entityaccesscount":"value":2,"limit":400,"timingprofile":["100.00% 1219.364 1 -total"," 27.77% 338.576 2 Template:Reflist"," 20.89% 254.772 30 Template:Cite_book"," 18.70% 228.019 6 Template:Lang"," 7.10% 86.549 1 Template:Science"," 6.15% 74.989 5 Template:ISBN"," 4.58% 55.821 1 Template:Authority_control"," 4.43% 54.073 1 Template:Page_needed"," 4.43% 53.960 1 Template:Merge_from"," 4.15% 50.662 1 Template:Fix"],"scribunto":"limitreport-timeusage":"value":"0.617","limit":"10.000","limitreport-memusage":"value":20432252,"limit":52428800,"cachereport":"origin":"mw1262","timestamp":"20190107193135","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false);mw.config.set("wgBackendResponseTime":106,"wgHostname":"mw1238"););