Great Northern Railway (U.S.)

| |

GN system map, circa 1918; dotted lines represent nearby railroads | |

Great Northern 400, a preserved EMD SD45. | |

| Reporting mark | GN |

|---|---|

| Locale | British Columbia California Idaho Iowa Manitoba Minnesota Montana North Dakota Oregon South Dakota Washington Wisconsin |

| Dates of operation | 1857–1970 |

| Successor | Burlington Northern Railroad |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Length | 8,368 miles (13,467 kilometres) |

| Headquarters | Saint Paul, Minnesota |

GN's 4-8-4 S-2 "Northern" class locomotive #2584 and nearby sculpture, U.S.–Canada Friendship in Havre, Montana

The Great Northern Railway (reporting mark GN) was an American Class I railroad. Running from Saint Paul, Minnesota, to Seattle, Washington, it was the creation of 19th-century railroad entrepreneur James J. Hill and was developed from the Saint Paul & Pacific Railroad. The Great Northern's (GN) route was the northernmost transcontinental railroad route in the U.S.

In 1970 the Great Northern Railway merged with three other railroads to form the Burlington Northern Railroad, which merged in 1996 with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway to form the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway.

The Great Northern was the only privately funded – and successfully built – transcontinental railroad in U.S. history.[1][2] No federal subsidies were used during its construction, unlike all other transcontinental railroads.[1]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Mainline

1.2 Settlements

1.3 Later history

2 In popular culture

3 Passenger service

3.1 Named trains

3.2 Unnamed trains

4 Rails to trails

5 See also

6 Footnotes

7 References

8 External links

History

The Great Northern was built in stages, slowly to create profitable lines, before extending the road further into the undeveloped Western territories. In a series of the earliest public relations campaigns, contests were held to promote interest in the railroad and the ranchlands along its route. Fred J. Adams used promotional incentives such as feed and seed donations to farmers getting started along the line. Contests were all-inclusive, from largest farm animals to largest freight carload capacity and were promoted heavily to immigrants and newcomers from the East.[3]

The earliest predecessor railroad to the GN was the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, a bankrupt railroad with a small amount of track in the state of Minnesota. James Jerome Hill convinced John S. Kennedy (a New York banker), Norman Kittson (Hill's friend and a wealthy fur trader), Donald Smith (an executive with Canada's Hudson's Bay Company), George Stephen (Smith's cousin and president of the Bank of Montreal), and others to invest $5.5 million in purchasing the railroad.[4] On March 13, 1878, the road's creditors formally signed an agreement transferring their bonds and control of the railroad to Hill's investment group.[5] On September 18, 1889, Hill changed the name of the Minneapolis and St. Cloud Railway (a railroad which existed primarily on paper, but which held very extensive land grants throughout the Midwest and Pacific Northwest) to the Great Northern Railway. On February 1, 1890, he transferred ownership of the StPM&M, Montana Central Railway, and other rail systems he owned to the Great Northern.[6]

The Great Northern had branches that ran north to the Canada–US border in Minnesota, North Dakota, and Montana. It also had branches that ran to Superior, Wisconsin, and Butte, Montana, connecting with the iron mining fields of Minnesota and copper mines of Montana. In 1898 Hill purchased control of large parts of the Messabe Range iron mining district in Minnesota, along with its rail lines. The Great Northern began large-scale shipment of ore to the steel mills of the Midwest.[7] At its height, Great Northern operated over 8,000 miles.

Revenue freight traffic, in millions of net ton-miles (incl FG&S; not incl PC or MA&CR)

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 8521 |

| 1933 | 5434 |

| 1944 | 19583 |

| 1960 | 15831 |

| 1967 | 17938 |

The railroad’s best known engineer was John Frank Stevens, who served from 1889 to 1903. Stevens was acclaimed for his 1889 exploration of Marias Pass in Montana and determined its practicability for a railroad. Stevens was an efficient administrator with remarkable technical skills and imagination. He discovered Stevens Pass through the Cascade Mountains, set railroad construction standards in the Mesabi Range of northern Minnesota, and supervised construction of the Oregon Trunk Line. He then became the chief engineer of the Panama Canal.[8]

The logo of the railroad, a Rocky Mountain goat, was based on a goat William Kenney, one of the railroad's presidents, had used to haul newspapers as a boy.[9][10][11]

Mainline

The mainline began at Saint Paul, Minnesota, heading west and topping the bluffs of the Mississippi River, crossing the river to Minneapolis on a massive multi-piered stone bridge. The Stone Arch Bridge stands in Minneapolis, near the Saint Anthony Falls, the only waterfall on the Mississippi. The bridge ceased to be used as a railroad bridge in 1978 and is now used as a pedestrian river crossing with excellent views of the falls and of the lock system used to grant barges access up the river past the falls. The mainline headed northwest from the Twin Cities, across North Dakota and eastern Montana. The line then crossed the Rocky Mountains at Marias Pass, and then followed the Flathead River and then Kootenai River to Athol, Idaho, and Spokane, Washington. From here, the mainline crossed the Cascade Mountains through the Cascade Tunnel under Stevens Pass, reaching Seattle, Washington, in 1893, with the driving of the last spike at Scenic, Washington, on January 6, 1893.

The main line west of Marias Pass has been relocated twice. The original route over Haskell Pass, via Kalispell and Marion, Montana was replaced in 1904 by a more circuitous but flatter route via Whitefish and Eureka, joining the Kootenai River at Rexford, Montana. A further reroute was necessitated by the construction of the Libby Dam on the Kootenai River in the late 1960s. The Army Corp of Engineers built a new route through the Salish Mountains, including the 7-mile-long Flathead Tunnel, second-longest in the United States, to relocate the tracks away from the Kootenai River. This route opened in 1970. The surviving portions of the older routes (from Columbia Falls to Kalispell and Stryker to Eureka, are now operated by Watco as the Mission Mountain Railroad.

The Great Northern mainline crossed the continental divide through Marias Pass, the lowest crossing of the Rockies south of the Canada–US border. Here, the mainline forms the southern border of Glacier National Park, which the GN promoted heavily as a tourist attraction. GN constructed stations at East Glacier and West Glacier entries to the park, stone and timber lodges at the entries and other inns and lodges throughout the Park. Many of the structures have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places due to unique construction, location and the beauty of the surrounding regions.

In 1931 the GN also developed the "Inside Gateway," a route to California that rivaled the Southern Pacific Railroad's route between Oregon and California. The GN route was further inland than the SP route and ran south from the Columbia River in Oregon. The GN connected with the Western Pacific at Bieber, California; the Western Pacific connected with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe in Stockton, California, and together the three railroads (GN, WP, and ATSF) competed with Southern Pacific for traffic between California and the Pacific Northwest. With a terminus at Superior, Wisconsin, the Great Northern was able to provide transportation from the Pacific to the Atlantic by taking advantage of the shorter distance to Duluth from the ocean, as compared to Chicago.

Settlements

A 1909 ad aimed at settlers from a St. Paul Newspaper

The Great Northern energetically promoted settlement along its lines in North Dakota and Montana, especially by Germans and Scandinavians from Europe. The Great Northern bought its lands from the federal government – it received no land grants – [citation needed] and resold them to farmers one by one. It operated agencies in Germany and Scandinavia that promoted its lands, and brought families over at low cost, building special colonist cars to transport immigrant families. The rapidly increasing settlement in North Dakota's Red River Valley along the Minnesota border between 1871 and 1890 was a major example of large-scale "bonanza" farming.[12][13][14]

Later history

On March 2nd, 1970 the Great Northern, together with the Northern Pacific Railway, the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway merged to form the Burlington Northern Railroad. The BN operated until 1996, when it merged with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway to form the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway.

In popular culture

The Great Northern Railway is considered to have inspired (in broad outline, not in specific details) the Taggart Transcontinental railroad in Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged.[15]

The railroad is mentioned in the lyrics of the Grateful Dead song Jack Straw: "Great Northern, out of Cheyenne, from sea to shining sea".

In Season One of Hey Arnold, the episode "Haunted Train" depicts the fictitious Engine 25, a 4-8-2 under the GNR mantle wrecked near Arnold's hometown due to a psychotic engineer. Now the ghost of the train apparently picks up unsuspecting passengers and takes them to Hell, driven by the insane engineer.

Revenue freight traffic, in millions of net ton-miles (incl FG&S; not incl PC or MA&CR)

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 8521 |

| 1933 | 5434 |

| 1944 | 19583 |

| 1960 | 15831 |

| 1967 | 17938 |

Passenger service

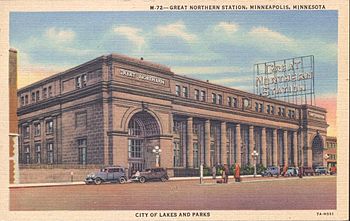

Great Northern Station, Minneapolis, Minnesota, which also served the Northern Pacific Railway. This historic depot was razed in 1978.

GN operated various passenger trains but the Empire Builder was their premier passenger train. It was named in honor of James J. Hill, known as the "Empire Builder." Amtrak's Empire Builder operates over much of the same route formerly covered by GN's train of the same name.

Named trains

Alexandrian: St. Paul–Fargo

Badger Express: St. Paul-Superior/Duluth (later renamed Badger)

Cascadian: Seattle–Spokane (1909-1959)

Dakotan: St. Paul-Minot

Eastern Express: Seattle-St. Paul (1903–1906) (replaced by Fast Mail in 1906)[16]

Empire Builder: Chicago-Seattle/Portland (1929–present)

Fast Mail No. 27: St. Paul–Seattle (1906–1910) (renamed The Oregonian in 1910)[16]

Glacier Park Limited: St. Paul–Seattle (1915-1929) (replaced by Oriental Limited in 1929)[16]

Gopher: St. Paul-Superior/Duluth

Great Northern Express: (1909-1918) Kansas City-Seattle[17][18]

International: Seattle-Vancouver, B.C.

Oregonian : St. Paul–Seattle (1910–1915) (replaced by Glacier Park Limited in 1915)[16]

Oriental Limited : Chicago-St. Paul-Seattle (replaced by Western Star in 1951)

Puget Sound Express: St. Paul-Seattle (1903–1906) (replaced by Fast Mail in 1906)[16]

Red River Limited: Grand Forks-St. Paul (later renamed Red River)

Seattle Express[19]

Southeast Express: (1909–1918) Seattle-Kansas City[17][20]

Western Star : Chicago-St. Paul-Seattle-Portland

Winnipeg Limited: St. Paul-Winnipeg

Unnamed trains

|

|

Rails to trails

In addition to the Stone Arch Bridge, parts of the railway has been turned into pedestrian and bicycle trails. In Minnesota, the Cedar Lake Trail is built in areas that were formerly railroad yards for the Great Northern Railway and the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway. Also in Minnesota, the Dakota Rail Trail is built on 26.5 miles of the railroad right-of-way. Further west, the Iron Goat Trail in Washington follows the late 19th-century route of the Great Northern Railway through the cascades and gets its name from the railway's logo.[21][22]

See also

- Western Fruit Express

- Cascade Tunnel

- Great Northern Railway: Mansfield Branch (1909-1985)

- Glacier National Park (U.S.)

W-1 GN's largest electric locomotive

Footnotes

^ ab "James J. Hill: Transforming the American Northwest - Daniel Oliver". fee.org. 1 July 2001. Retrieved 4 May 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-03-07. Retrieved 2018-02-01.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Martin (1991), chpt. 12.

^ Malone (1996), p. 38-41.

^ Malone (1996), p. 49.

^ Yenne (2005), p. 23.

^ Hofsommer (1996).

^ Hidy & Hidy (1969).

^ The Great Northern Goat. 10-15. 1939. p. 11.

^ Downs, Winfield Scott (1940). Encyclopedia of American Biography. American Historical Company.

^ ""Kenney's Goat" Story Recalled". Spokane Daily Chronicle. November 12, 1931. p. 1.

^ Murray (1957), p. 57-66.

^ Hickcox (1983), p. 58-67.

^ Zeidel (1993), p. 14–23.

^ Rand, Peikoff & Schwartz (1989), p. 92.

^ abcde "Glacier Park Limited". Ted's Great Northern Homepage. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

^ ab "Transcontinental Trains". Ted's Great Northern Homepage. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

^ "Great Northern Express". Ted's Great Northern Homepage. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

^ "Archives West: Great Northern Railway Company Wellington Disaster records, 1907-1911". nwda-db.wsulibs.wsu.edu. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

^ "Three Daily Trains". Great Northern Railway. c. 1912. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

^ Andrew Weber; Bryce Stevens (1 February 2010). 60 Hikes Within 60 Miles: Seattle: Including Bellevue, Everett, and Tacoma. Menasha Ridge Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-89732-812-8. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018.

^ Mike McQuaide (2005). Day Hike! Central Cascades: The Best Trails You Can Hike in a Day. Sasquatch Books. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-57061-412-5. Archived from the original on 2018-05-04.

References

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Doyle, Ted. "Great Northern Flyer". Teds' Great Northern Homepage.

Hickcox, David H. "The Impact of the Great Northern Railway on Settlement in Northern Montana, 1880-1920". Railroad History. 148 (Spring 1983): 58–67. JSTOR 43523868.

Hidy, Ralph; Hidy, Muriel E. (1969). "John Frank Stevens, Great Northern Engineer" (PDF). Minnesota History. 41 (8): 345–361.

Hidy, Ralph W.; Hidy, Muriel E.; Scott, Roy V.; Hofsummer, Don L. (2004) [1988]. The Great Northern Railway: A History. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press. ISBN 978-0-816-64429-2. OCLC 54885353.

Martin, Albro (1991). James J. Hill and the Opening of the Northwest. Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0873512619.

Hofsommer, Don L. "Ore Docks and Trains: The Great Northern Railway and the Mesabi Range". Railroad History. 174 (Spring 1996): 5–25. JSTOR 43521883.

Malone, James P. (1996). James J. Hill: Empire Builder of the Northwest. Norman, OK, USA: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806128603.

Rand, Ayn; Peikoff, Leonard; Schwartz, Peter (1989). The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought. New American Library.

Sherman, T. Gary (2004). Conquest and Catastrophe: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Great Northern Railway Through Stevens Pass. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. ISBN 1-4184-9575-1.

Sobel, Robert (1974). "Chapter 4: James J. Hill". The Entrepreneurs: Explorations within the American business tradition. Weybright & Talley. ISBN 0-679-40064-8.

Murray, Stanley N. (1957). "Railroads and the Agricultural Development of the Red River Valley of the North, 1870-1890". Agricultural History. 31 (4).

Whitney, F.I. (1894). "Valley, Plain and Peak..Scenes on the line of the Great northern railway". St. Paul, Minnesota: Great Northern Railway Office of the general passenger and ticket agent.

Wilson, Jeff (2000). Great Northern Railway in the Pacific Northwest (Golden Years of Railroading). Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. ISBN 0-89024-420-0.

Wood, Charles (1989). Great Northern Railway. Edmonds, Washington: Pacific Fast Mail. ISBN 0-915713-19-5.

Yenne, Bill (2005). Great Northern Empire Builder. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI. ISBN 0-7603-1847-6.

Zeidel, Robert F (1993). "Peopling the Empire: The Great Northern Railroad and the Recruitment of Immigrant Settlers to North Dakota". North Dakota History. 60 (2): 14–23.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Northern Railway (US). |

- Fort Langley

Great Northern Railway Company Records, Minnesota Historical Society.- Great Northern Railway Historical Society

- The Great Northern Empire — Then and Now

- The Great Northern Railway

- Great Northern Railway Page

Great Northern Railway Post Office Car No. 42 — photographs and short history of one of six streamlined baggage-mail cars built for the Great Northern by the American Car and Foundry Company in 1950.- Burlington Northern Adventures: Railroading in the Days of the Caboose, written by former brakeman, conductor and trainmaster William J. Brotherton

- Great Northern History, photos and O gage model railroad.

- Great Northern Railway route map (1920)

University of Washington Libraries: Digital Collections:

Lee Pickett Photographs Over 900 photographs documenting scenes from Snohomish, King and Chelan Counties in Washington state from the early 1900s to the 1940s. Includes images of the Great Northern Railway.

Transportation Photographs An ongoing digital collection of photographs depicting various modes of transportation in the Pacific Northwest region and Western United States during the first half of the 20th century. Includes images of the Great Northern Railway.

Dutiful Son: Louis W. Hill Sr. Book, Book about Louis W. Hill Sr., son and successor of empire builder James J. Hill at Ramsey County Historical Society.- "The Egotistigraphy", by John Sanford Barnes. An autobiography, including his role in the early financing of the Great Northern Railway and the career of James J. Hill, privately printed 1910. Internet edition edited by Susan Bainbridge Hay 2012