Sylheti language

| Sylheti ꠍꠤꠟꠐꠤ | |

|---|---|

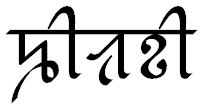

ꠍꠤꠟꠐꠤ ছিলটি সিলেটি | |

The word Silôṭi ('Sylheti') in Sylheti Nagari script | |

| Pronunciation | [silɔʈi] |

| Native to | Bangladesh, India |

| Region | Sylhet Division, Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, Manipur |

| Ethnicity | Sylheti people |

Native speakers | 11 million (2007)[1] |

Language family | Indo-European

|

Writing system | Sylheti Nagari, Bengali script |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | syl |

| Glottolog | sylh1242[2] |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-ui |

Sylheti speakers within South Asia | |

Sylheti (Sylheti: ꠍꠤꠟꠐꠤ, Bengali: সিলেটি) is an Indo-Aryan language, primarily spoken in the Sylhet Division of Bangladesh and in the Barak Valley of the Indian state of Assam. There is a substantial number of speakers in the Indian states of Meghalaya, Manipur and Tripura (North Tripura) with smaller populations in Kolkata and Nagaland.[3]

Contents

1 Status

2 Name of the language

3 Geographical distribution

3.1 Dialects

4 History

5 Sylheti variation from Standard Bengali

5.1 Vocabulary look

5.2 Grammar comparisons

6 Tone

7 Phonology

8 References

9 External links

Status

The status of Sylheti is hotly disputed with some considering it a dialect of Bengali, while others consider it a separate language.[4] There are significant differences in grammar and pronunciation as well as a lack of mutual intelligibility between the two varieties. There are greater differences between Sylheti and Bengali than between Sylheti and Assamese, which is recognised as a separate language.[5] Most Sylhetis are at least bilingual to some degree, as Bengali is taught at all levels of education in Bangladesh. Sylhet was part of the ancient kingdom of Kamarupa,[6] and Sylheti shares many common features with Assamese, including having a larger set of fricatives than other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages. According to George Abraham Grierson,[7] "The inflections also differ from those of regular Bengali, and in one or two instances assimilate to those of Assamese". Considering the unique linguistic properties such as phoneme inventory, allophony, and inflectional morphology in particular and lexicon in general, Sylheti is often regarded as a separate language (Grierson 1928, Chatterjee 1939, Gordon 2005). Indeed, it was formerly written using its own script, Sylheti Nagari, which, although largely replaced with the Bengali script in recent times, is beginning to experience a revival in use.

Sylheti shares at least 80% of its lexicon with Bengali.[8]

Name of the language

Sylheti is the common English spelling of the language name after the accepted British spelling of the Sylhet District. The Standard Bengali spelling of the name Sylheti is সিলেটি (Sileṭi). The Sylheti spelling is ꠍꠤꠟꠐꠤ or ছিলটি (Silôṭi). In Assamese it is called ছিলঠীয়া (Silothia).

Geographical distribution

The Sylheti language is native to the Greater Sylhet region, which comprises the present-day Sylhet Division of Bangladesh as well as the 3 districts of the Barak Valley in India.

Besides the native region it is also spoken by the Sylhetis living in North Tripura and the Meghalaya region. A significant amount of Sylheti migration to the United Kingdom and the United States from the 20th century has made Sylheti one of the most spoken languages of the Bangladeshi diaspora.

Dialects

The Sylhet region became a part of the Bengal Sultanate in 1303 during the Conquest of Sylhet led by Shamsuddin Firoz Shah. This led to influence from Arabic and Persian. When the British arrived in 1765, Sylhet became a part of Assam leading to Assamese influence on the language. Following the 1947 referendum, majority decided to join East Bengal and the Hill Tracts to form East Pakistan. However, due to the Radcliffe Line, the districts of Karimganj, Hailakandi and Cachar were separated from Sylhet and joined Assam. Due to this separation, the Sylheti language has evolved into many dialects.

1. Jalalabadi Sylheti: This dialect is mostly spoken in the Sylhet, Moulvibazar and Habiganj districts. It is heavily influenced by Arabic and Persian due to arrival of Islam in the region. Named after Shah Jalal, it is mostly spoken by the Muslim population although Hindus in these areas may also speak in this dialect. Covering most of the Sylhet region, there are slight differences in vocabulary which can still be seen although it is one dialect. This dialect is also viewed as the standard version of Sylheti.

2. Lauṛi Sylheti/Sunamganji Sylheti: Named after the Lauṛ Kingdom which comprises modern-day Sunamganj as well as neighbouring districts. Baul Shah Abdul Karim is known for singing in this dialect. It may also be known as Sunamganji. This dialect is closer to the Bengali language than the standard Jalalabadi.

3. Jaintian Sylheti/Shillong Sylheti: Influenced by Sanskrit due to majority of speakers being Sylheti Hindus. It is spoken in the city of Shillong, Meghalaya and other Sylheti-populated areas of the Jaintia Hills. It is also known as Shillong Sylheti.

4. Barak Sylheti: Spoken in the Barak Valley and some other areas in Assam. It is influenced by the Assamese due to the population being part of the Assam state. It is also spoken by people of the North Tripura.

5. There is also a written form of Sylheti which was used to write Puthis and was identical to puthis written in Dobhashi Bengali due to both lacking the use of tatsama and using Perso-Arabic vocabulary as a replacement. Similar to Dobhashi, those written in Sylheti Nagri were paginated from right to left.[9][10]

History

SAMPLE TEXT:

Front page of a Nagari book titled Halat-un-Nabi, written in the mid-19th century by Sadeq Ali of Sylhet

In ancient literature, Sylhet was referred as Shilahat and Shilahatta.[11] In the 19th century, the British tea-planters in the area referred to the vernacular spoken in Surma and Barak Valleys as Sylheti language.[12] In Assam, the language is still referred to as Sylheti.

During the British colonial period, a Sylheti student by the name of Moulvi Abdul Karim studying in London, England, after completing his education, spent several years in London and learned the printing trade. After returning home, he designed a woodblock type for Sylheti Nagari and founded the Islamia Press in Sylhet Town in about 1870. Other Sylheti presses were established in Sunamganj, Shillong and Kolkata. These presses fell out of use during the early 1970s.[13][14] Since then, the Sylotinagri alphabet has been used mainly by linguists and academics.[15] It gradually became very unpopular.[16][17]

The script includes 5 independent vowels, 5 dependent vowels attached to a consonant letter and 27 consonants. The Sylheti abugida differs from the Bengali alphabet as it is a form of Kaithi, a script that belongs to the main group of North Indian scripts of Bihar.[18] The writing system's main use was to record religious poetry, described as a rich language and easy to learn.[19]

Campaigns started to rise in London during the mid-1970s to mid-1980s to recognise Sylheti as a language in its own right. During the mid-1970s, when the first mother-tongue classes were established for Bangladeshis by community activists, the classes were given in standard Bengali rather than the Sylheti dialect which triggered the campaign. During the 1980s, a recognition campaign for Sylheti took place in the area of Spitalfields, East End of London. One of the main organisations was the Bangladeshis' Educational Needs in Tower Hamlets (usually known by its acronym as BENTH). However this organisation collapsed in 1985 and with its demise, the pro-Sylheti campaign in the borough lost impetus. Nonetheless, Sylheti remains very widespread as a domestic language in working-class as well as upper-class Sylheti households in the United Kingdom.[20]

Sylheti variation from Standard Bengali

Vocabulary look

A phrase in:

- Standard Bengali: এক দেশের গালি আরেক দেশের বুলি æk desher gali arek desher buli.

- Sylheti: ꠄꠇ ꠖꠦꠡꠞ ꠉꠣꠁꠟ ꠀꠣꠞꠇ ꠖꠦꠡꠞ ꠝꠣꠔ/এক দেশর গাইল, আরক দেশর মাত ex deshôr gail arôx deshôr mat.

which literally means "one land's obscenity is another land's language", and can be roughly translated to convey that a similar word in one language can mean something very different in another. For example:

মেঘ megh in Standard Bengali means cloud .

- ꠝꠦꠊ/মেঘ megh in Sylheti means rain.

- In Pali মেঘ megh means both rain and cloud.

- In Sylheti cloud is called ꠛꠣꠖꠟ/বাদল badôl, ꠢꠣꠎ/হাজ haz, or ꠀꠡꠝꠣꠘꠤ ꠢꠣꠎ/আসমানি হাজ ashmani haz (decor of the sky).

- In Standard Bengali rain is called বৃষ্টি brishti.

নাড়া naṛa in Standard Bengali means to stir or to move .

- In Sylheti, to stir is called laṛa (ꠟꠣꠠꠣ).

কম্বল kômbôl in Standard Bengali means blanket.

- In Sylheti, blanket is called ꠞꠣꠎꠣꠁ/রাজাই razai.

- ꠇꠝꠛꠟ/কম্বল xômbôl in Sylheti means buttock.

Grammar comparisons

The following is a sample text in Sylheti, of the Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations:

Sylheti in Sylheti Nagari script

ꠗꠣꠞꠣ ১: ꠢꠇꠟ ꠝꠣꠘꠥ ꠡꠣꠗꠤꠘꠜꠣꠛꠦ ꠢꠝꠣꠘ ꠁꠎ꠆ꠎꠔ ꠀꠞ ꠢꠇ ꠟꠁꠀ ꠙꠄꠖꠣ ‘ꠅꠄ। ꠔꠣꠞꠣꠞ ꠛꠤꠛꠦꠇ ꠀꠞ ꠀꠇꠟ ꠀꠍꠦ। ꠅꠔꠣꠞ ꠟꠣꠉꠤ ꠢꠇꠟꠞ ꠄꠇꠎꠘꠦ ꠀꠞꠇꠎꠘꠞ ꠟꠉꠦ ꠛꠤꠞꠣꠖꠞꠤꠞ ꠝꠘ ꠟꠁꠀ ꠀꠌꠞꠘ ꠇꠞꠣ ꠃꠌꠤꠔ।

Sylheti in Bengali script

ধারা ১: হকল মানু স্বাধীনভাবে হমান ইজ্জত আর হক লইয়া পয়দা ‘অয়। তারার বিবেক আর আকল আছে। অতার লাগি হকলর একজনে আরকজনর লগে বিরাদরির মন লইয়া আচরণ করা উচিত।

Sylheti in Phonetic Romanization

Dara ex: Hôxôl manu šadinbabe hôman ijjôt ar hôx lôia fôeda ôe. Tarar bibex ar axôl ase. Ôtar lagi hôxlôr exzône arôxzônôr lôge biradôrir môn lôia asôrôn xôra usit.

Sylheti in IPA

- /d̪aɾa ex | ɦɔxɔl manu ʃad̪ínbábe ɦɔman id͡ʒːɔt̪ aɾ ɦɔx lɔia fɔe̯d̪a ɔ́e̯ ‖ t̪aɾaɾ bibex aɾ axɔl asé ‖ ɔt̪aɾ lagi ɦɔxlɔɾ exzɔne arɔxzɔnɔɾ lɔge birad̪ɔɾiɾ mɔn lɔia asɔɾɔn xɔɾa usit̪ ‖/

Bengali in Bengali script

ধারা ১: সমস্ত মানুষ স্বাধীনভাবে সমান মর্যাদা এবং অধিকার নিয়ে জন্মগ্রহণ করে। তাঁদের বিবেক এবং বুদ্ধি আছে; সুতরাং সকলেরই একে অপরের প্রতি ভ্রাতৃত্বসুলভ মনোভাব নিয়ে আচরণ করা উচিত।

Bengali in Phonetic Romanization

Dhara æk: Šômôsto manuš šadhinbhabe šôman môrjada æbông odhikar niye jônmôgrôhôn kôre. Tãder bibek æbông buddhi achhe; šutôrang šôkôleri æke ôpôrer prôti bhratrittôšulôbh mônobhab niye achôrôn kôra uchit.

Bengali in IPA

- /d̪ʱara ɛk | ʃɔmɔst̪o manuʃ ʃad̪ʱinbʱabe ʃɔman mɔɾd͡ʒad̪a ɛbɔŋ od̪ʱikaɾ nije d͡ʒɔnmɔgɾɔɦɔn kɔɾe ‖ t̪ãd̪eɾ bibek ɛbɔŋ bud̪d̪ʱi at͡ʃʰe ‖ ʃut̪ɔɾaŋ ʃɔkɔleɾi ɛke ɔpɔɾeɾ prɔt̪i bʱɾat̪ɾit̪ːɔʃulɔbʱ mɔnobʱab nije at͡ʃɔɾɔn kɔɾa ut͡ʃit̪ ‖/

Below are the grammar similarities and differences appearing in a word to word comparison:

Sylheti word-to-word gloss

- All humans' born happen free and dignity plus rights with. Their conscious, intelligent and judgement-clever staying bearing a-person another-person's with spiritual brotherhood conduct stays.

Bengali word-to-word gloss

- All human free-manner-in equal dignity and right taken birth-take do. Their reason and intelligence exist; therefore everyone-indeed one another's towards brotherhood-ly attitude taken conduct do should.

English

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Tone

Sylheti is a tonal language. The Indo-Aryan languages are not generally recognized for tone. There are two types of tonal contrasts in Sylheti: the emergence of high tone in the vowels following the loss of aspiration, and a low tone elsewhere.[21]

at (ꠀꠔ) 'intestine'

át (ꠀ’ꠔ) 'hand'

xali (ꠇꠣꠟꠤ) 'ink'

xáli (ꠈꠣꠟꠤ) 'empty'

guṛa (ꠉꠥꠠꠣ) 'powder'

gúṛa (ꠊꠥꠠꠣ) 'horse'

suri (ꠌꠥꠞꠤ) 'theft'

súri (ꠍꠥꠞꠤ) 'knife'

zal (ꠎꠣꠟ) 'net, web'

zál (ꠏꠣꠟ) 'pungent'

ṭik (ꠐꠤꠇ) 'tick'

ṭík (ꠑꠤꠇ) 'correct'

ḍal (ꠒꠣꠟ) 'branch'

ḍál (ꠓꠣꠟ) 'shield'

tal (ꠔꠣꠟ) 'palmyra, rhythm'

tál (ꠕꠣꠟ) 'plate'

dan (ꠖꠣꠘ) 'donation'

dán (ꠗꠣꠘ) 'paddy'

ful (ꠙꠥꠟ) 'bridge'

fúl (ꠚꠥꠟ) 'flower'

bala (ꠛꠣꠟꠣ) 'bangle'

bála (ꠜꠣꠟꠣ) 'good, welfare'

bat (ꠛꠣꠔ) 'arthritis'

bát (ꠜꠣꠔ) 'rice'

Sylheti continues to have a long history of coexisting with other Tibeto-Burman languages such as various dialects of Kokborok, Reang which are tonal in nature. Even though there is no clear evidence of direct borrowing of lexical items from those tonal languages into Sylheti, there is still a possibility that the emergence of Sylheti tones is due to an areal feature as the indigenous speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages by and large use Sylheti as a common medium for interaction.

Phonology

Sylheti is distinguished by its tonal characteristics and a wide range of fricative consonants corresponding to aspirated consonants in closely related languages and dialects such as Bengali; a lack of the breathy voiced stops; word-final stress; and a relatively large set of loanwords from Assamese, Standard Bengali and other Bengali dialects. Sylheti has affected the course of Standard Bengali in the rest of the state.

A notable characteristic of spoken Sylheti is the correspondence of the /ʜ/ (hereafter transliterated x), pronounced as a Voiceless epiglottal fricative to the [ʃ], or "sh", of Bengali, e.g.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Standard Bengali | Assamese | Sylheti | Transliteration | Meaning in English | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| চরণস্পর্শ Côrônspôrshô | ভৰি চোৱা Bhori süa | ꠇꠖꠝꠛꠥꠍꠤ Xôdômbusi | /xɔdɔmbusi/ | Touching the feet (A way showing respect) | |

| ঢাকা Dhaka | ঢাকা Dhaka | ꠓꠣꠇꠣ Daxa | /ɖaxa/ | Dhaka | |

| একজন লোক Ēkjôn lōk | এজন লোক Ezon lük | ꠄꠇꠎꠘ ꠝꠣꠘꠥꠡ Ēxzôn manush | /exzɔn manuʃ/ | A person | |

একজন Ekjôn | এজন Ezon | ꠄꠇꠎꠘ Exzôn | /exzɔn/ | Someone | |

| একজন পুরুষ Ekjôn purush | এজন মানুহ Ezon manuh | ꠄꠇꠐꠣ ꠛꠦꠐꠣ Exta beta | /exʈa beʈa/ | A man | |

| কীসের Kisher | কিহৰ kihor | ꠇꠤꠅꠞ Kior | /kioɾ/ | Informal of Whereof | |

| কন্যা, মেয়ে Kônna, Meye | জী, ছোৱালী Zi, Süali | ꠇꠂꠘ꠆ꠘꠣ, ꠏꠤ, ꠙꠥꠠꠤ Xôinna, Zi, Furi | /xoinna/, /zi/, /ɸuɽi/ | Daughter | |

| মানবজাতি Manôbjati | মানৱজাতি, মানুহৰ জাতি Manowzati, Manuhor zati | ꠝꠣꠁꠘꠡꠞ ꠎꠣꠔ Mainshor zat | /mainʃɔɾ zat̪/ | Mankind | |

| অসমিয়া, অহমিয়া Ôshômiya, Ôhômiya | অসমীয়া Oxomiya | ꠅꠢꠝꠤꠀ Ôhômia | /ɔɦɔmia/ | Assamese people | |

| আঙুল Angul | আঙুলি Anguli | ꠀꠋꠉꠥꠁꠟ Angguil | /aŋguil/ | Finger, toe | |

| আংটি Angti | আঙুঠি Anguthi | ꠀꠋꠑꠤ Angti | /aŋʈi/ | Ring | |

| আগুনপোড়া Agunpora | জুইত পোৰা, জুইত সেকা Zuit püra, Zuit xeka | ꠀꠉꠥꠁꠘꠙꠥꠞꠣ Aguinfura | /aguinfuɽa/ | Baked, grilled | |

| অসিধারী Oshidhari | খৰ্গধৰ,চোকৰধৰা Khorgodhor, Sükordhora | ꠔꠟꠥꠀꠞꠗꠣꠞꠤ Tôluardari | /t̪ɔluaɾd̪aɾi/ | Swordsman | |

| পাখি, পক্ষী Pakhi, Pôkkhi | চৰাই, পখী Sorai, Pokhi | ꠙꠣꠈꠤ, ꠙꠣꠈꠤꠀ Faki, Fakia | /ɸaki/, /ɸakia/ | Bird | |

| ভালোবাসা, প্রেম, পিরিতি Bhalobasha, Prem, Piriti | মৰম, ভালপোৱা, প্রেম, পিৰিটি Morom, Bhalpüwa, Prem, Piriti | ꠜꠣꠟꠣꠙꠣꠅꠣ, ꠙꠦꠞꠦꠝ, ꠙꠤꠞꠤꠔꠤ, ꠝꠢꠛ꠆ꠛꠔ Balafawa, Ferem, Firiti, Môhôbbôt | Firiti | /balaɸawa/, /ɸeɾem/, /ɸiɾit̪i/, /mɔɦɔbbɔt̪/ | Love |

| পরে Pôre | পিছত, পৰত pisot, porot | ꠙꠞꠦ, ꠛꠣꠖꠦ Fôre, Bade | /ɸɔɾe/, /bad̪e/ | Later | |

| সকল, সমস্ত, সব Shôkôl, Shômôsto, Shôb | সকলো, সব, চব Xokolü; Xob; Sob | ꠢꠇꠟ, ꠢꠇ꠆ꠇꠟ, ꠡꠛ Hôxôl, Hôkkôl, Shôb | /ɦɔxɔl/, /ɦɔkkɔl/, /ʃɔb/ | All | |

| সারা Shara | গোটেই Gutei | ꠢꠣꠀꠣ Hara | /ɦaɾa/ | Whole | |

| সাত বিল Shat bil | সাত বিল Xat bil | ꠢꠣꠔ ꠛꠤꠟ Hat bil | /ɦat̪ bil/ | Seven wetlands | |

| সাতকড়া Shatkôra | সাতকৰা Xatkora | ꠢꠣꠔꠇꠠꠣ Hatxôra | /ɦat̪xɔɽa/ | Citrus macroptera fruit | |

| সাতবার Shatbar | সাতবাৰ Xatbar | ꠢꠣꠔꠛꠣꠞ Hatbar | /ɦat̪baɾ/ | Seven-times (Sylheti term for lots of time) | |

| সিলেটি Sileṭi | ছিলঠীয়া Silôṭiya | ꠍꠤꠟꠐꠤ Silôṭi | /silɔʈi/ | Sylheti | |

| সৌভাগ্য Shoubhaggô | সৌভাগ্য Xoubhaiggô | ꠈꠥꠡꠘꠍꠤꠛ, Shoubaiggô, Kushnôsib | /kuʃnɔsib/ | Good luck (Sylheti: God's Authority) | |

| ভালো করে খান। Bhalo kôre khan. | ভালকৈ খাওক। Bhalkoi khaük. | ꠜꠣꠟꠣ ꠇꠞꠤ ꠈꠣꠃꠇ꠆ꠇꠣ, ꠜꠣꠟꠣ ꠑꠤꠇꠦ ꠈꠣꠃꠇ꠆ꠇꠣ। Bala xôri xaukka, Bala tike xaukka. | /bala xɔɾi xaukka/, /bala ʈike xaukka/ | Bon appetit | |

| স্ত্রী, পত্নী StrI, Pôtni | ঘৈণী, পত্নী Stri, Ghôini, Pôtni | ꠛꠃ Bôu | /bɔu/ | Wife | |

| স্বামী, বর, পতি Shami, Bôr, Pôti | গিৰি, পৈ, স্বামী Swami, Giri, Pôti | ꠎꠣꠝꠣꠁ Zamai | /zamai/ | Husband | |

| জামাই Jamai | জোঁৱাই Züai | ꠖꠣꠝꠣꠘ Daman | /daman/ | Son-in-law | |

| শ্বশুর Shôshur | শহুৰ Xohur | ꠢꠃꠞ Hôur | /ɦɔúɾ/ | Father-in-law | |

| শাশুড়ি Shashuṛi | শাহু Xahu | ꠢꠠꠣ Hoṛi | /ɦɔɽi/ | Mother-in-law | |

| শালা Shala | খুলশালা Khulxala | ꠢꠣꠟꠣ Hala | /ɦala/ | Brother-in-law | |

| শালী Shali | খুলশালী Khulxali | ꠢꠣꠟꠤ Hali | /ɦali/ | Sister-in-law | |

| শেখা Shekha | শিকা Xika | ꠢꠤꠇꠣ Hika | /ɦika/ | Learn | |

| সরষে Shorshe | সৰিয়হ Xorioh | ꠢꠂꠞꠢ Hoiroh | /ɦoiɾoɦ/ | Mustard | |

| শিয়াল Shiyal | শিয়াল Xial | ꠢꠤꠀꠟ Hial | /ɦial/ | Fox, Jackal | |

| বেড়াল Beral | মেকুৰী, বিৰালী Mekuri, birali | ꠝꠦꠇꠥꠞ, ꠛꠤꠟꠣꠁ Mékur, Bilai | /mekuɾ/, /bilai/ | Cat | |

| শুঁটকি Shuṭki | শুকটি, শুকান মাছ Xukoti, Xukan mas | ꠢꠥꠐꠇꠤ, ꠢꠥꠇꠂꠘ Huṭki, Hukôin | /ɦuʈki/, /ɦukoin/ | Sundried Fish | |

| আপনার নাম কী? Apnar nam ki? | আপোনাৰ নাম কি? Apünar nam ki? | ꠀꠙꠘꠣꠞ ꠘꠣꠝ ꠇꠤꠔꠣ? Afnar nam kita? | /aɸnaɾ nam kit̪a/ | What's your name? | |

| ডাক্তার আসার পূর্বে রোগী মারা গেল। Daktar ashar purbe rogi mara gelo | ডাক্তৰ অহাৰ আগতেই ৰোগী মৰি গ’ল। Daktor ohar agotei rügi mori gól | ꠒꠣꠇ꠆ꠔꠞ ꠀꠅꠣꠞ ꠀꠉꠦꠃ ꠛꠦꠝꠣꠞꠤ ꠝꠞꠤ ꠉꠦꠟ। Daxtôr awar ageu bemari môri gelo. | /ɖaxt̪ɔɾ awaɾ ageu bemaɾi mɔɾi gelo/ | Before the doctor came, the patient had died. | |

| বহুদিন দেখিনি। Bôhudin dekhini. | বহুদিন দেখা নাই। Bohudin dekha nai. | ꠛꠣꠇ꠆ꠇꠣ ꠖꠤꠘ ꠖꠦꠈꠍꠤ ꠘꠣ। Bakka din dexsi na. | /bakka d̪in d̪exsi na/ | Long time, no see. | |

| আপনি কি ভালো আছেন? Apni ki bhalo Achen? | আপুনি ভালে আছে নে? Apuni bhale asê nê? | ꠀꠙꠘꠦ ꠜꠣꠟꠣ ꠀꠍꠂꠘ ꠘꠤ? Afne bala asôin ni? | /bála asoin ni/ | How are you? | |

| আমি তোমাকে ভালোবাসি। Ami tomake bhalobashi. | মই তোমাক ভাল পাওঁ। Moi tümak bhal paü. | ꠀꠝꠤ ꠔꠥꠝꠣꠞꠦ ꠜꠣꠟꠣ ꠙꠣꠁ। Ami tumare bala fai. | /ami t̪umare bála ɸai/ | I love you. | |

| আমি ভুলে গিয়েছি। Ami bhule giechi. | মই পাহৰি গৈছোঁ। Môi pahôri goisü. | ꠀꠝꠤ ꠙꠣꠅꠞꠤ ꠟꠤꠍꠤ। Ami faûri lisi. | /ami ɸaʊ́ɾi lisi/ | I have forgotten. | |

| মাংসের ঝোলটা আমার খুব ভালো লেগেছে। Mangsher jholṭa amar khub bhalo legeche. | মাংসৰ তৰকাৰীখন মোৰ খুব ভাল লাগিছে। Mangxor torkarikhon mür khub bhal lagise. | ꠉꠥꠍꠔꠞ ꠍꠣꠟꠘꠐꠣ ꠀꠝꠣꠞ ꠈꠥꠛ ꠜꠣꠟꠣ ꠟꠣꠉꠍꠦ। Gustôr salônṭa amar kub bala lagse. | /gust̪ɔɾ salɔnʈa amaɾ kúb bála lagse/ | I liked the meat curry. | |

| শিলচর কোনদিকে? Shilcôr kondike? | শিলচৰ কোন ফালে/পিনে? Xilsor kün fale/pine? | ꠢꠤꠟꠌꠞ ꠇꠥꠘ ꠛꠣꠄ/ꠛꠣꠁꠖꠤ/ꠝꠥꠈꠣ? Hilcôr kun bae/baidi/muka? | /ɦil͡tʃɔɾ kun bae, baid̪i, muka/ | Which way to Silchar? | |

| শৌচাগার কোথায়? Shôucagar kothay? | শৌচালয় ক’ত? Xousaloy kót? | ꠐꠣꠐ꠆ꠐꠤ ꠇꠥꠘꠈꠣꠘꠧ/ꠇꠥꠘꠣꠘꠧ/ꠈꠣꠘꠧ/ꠇꠁ? ṭaṭṭi kunxano/kunano/xano/xoi? | /ʈaʈʈi kunxano, kunano, xano, xoi/ | Where is the toilet? | |

| এটা কী? Eṭa ki? | এইটো কি? Eitü ki? | ꠁꠉꠥ/ꠁꠇꠐꠣ/ꠁꠐꠣ ꠇꠤꠔꠣ? Igu/Ikṭa/Iṭa kita? | /igu, ikʈa, iʈa kit̪a/ | What is this? | |

| সেটা কী? Sheṭa ki? | সেইটো কি? Xeitü ki? | ꠢꠤꠉꠥ/ꠢꠤꠇꠐꠣ/ꠢꠤꠐꠣ ꠇꠤꠔꠣ? Higu/Hikṭa/Hiṭa kita? | /ɦigu, ɦikʈa, ɦiʈa kit̪a/ | What is that? | |

| শেষ Shesh | শেষ Xex/xeh | ꠢꠦꠡ Hesh | /ɦeʃ/ | End, finish |

References

^ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Sylheti". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ "Sylheti". Ethnologue.

^ Sebastian M. Rasinger (2007). Bengali-English in East London: A Study in Urban Multilingualism. pp.F 26-27. Retrieved on 2017-05-02.

^ Glanville Price (2000). Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. pp. 91-92.

^ Edward Gait, History of Assam, p. 274

^ George Grierson, Language Survey of India, Vol II, Pt 1, p224

^ Chalmers (1996)

^ http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Sylheti_Nagri

^ d'Hubert, Thibaut (May 2014). "In the Shade of the Golden Palace: Alaol and Middle Bengali Poetics in Arakan".

^ James Lloyd-Williams & Sue Lloyd-Williams (Sylheti Translation and Research/STAR); Peter Constable (SIL International) Date: 1 November 2002

^ Grierson, George A. (1903). Linguistic Survey of India. Volume V, Part 1, Indo-Aryan family. Eastern group. Specimens of the Bengali and Assamese languages. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India.

^ Banglapedia

^ Archive

^ Sylheti Alphabets

^ Syloti Nagri alphabet

^ Sylheti unicode chart

^ Sylheti Literature

^ Sylheti Literature

^ Anne J. Kershen (2005). Strangers, Aliens and Asians: Huguenots, Jews and Bangladeshis in Spitalfields, 1660–2000. Routledge. pp. 148–150. ISBN 978-0-7146-5525-3.

^ Gope, Amalesh; Mahanta, Shakun (May 2014). "Lexical Tones in Sylheti". ResearchGate.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sylheti phrasebook. |

![]() Sylheti phrasebook travel guide from Wikivoyage

Sylheti phrasebook travel guide from Wikivoyage

- UK-Based Group that collects and republishes Sylheti literature