Status symbol

A status symbol is a perceived visible, external denotation of one's social position and perceived indicator of economic or social status.[1] Many luxury goods are often considered status symbols. Status symbol is also a sociological term – as part of social and sociological symbolic interactionism – relating to how individuals and groups interact and interpret various cultural symbols.[2]

Contents

1 By region and time

2 Societal recognition

3 Body modifications

4 Material possessions

5 See also

6 References

By region and time

Social status is often associated with clothing and possessions. Compare the foreman with a horse and high hat with the inquilino in picture. Image from 19th century rural Chile

As people aspire to high status, they often seek also its symbols. As with other symbols, status symbols may change in value or meaning over time, and will differ among countries and cultural regions, based on their economy and technology.

Military symbol of excellence

Galero hat, symbol of ecclesiastical status

For example, before the invention of the printing press, possession of a large collection of laboriously hand-copied books was a symbol of wealth and scholarship. In later centuries, books (and literacy) became more common, so a private library became less-rarefied as a status symbol, though a sizable collection still commands respect.

In some past cultures of East Asia, pearls and jade were major status symbols, reserved exclusively for royalty. Similar legal exclusions applied to the toga and its variants in ancient Rome, and to cotton in the Aztec Empire. Special colors, such as imperial yellow (in China) or royal purple (in ancient Rome) were reserved for royalty, with severe penalties for unauthorized display. Another common status symbol of the European medieval past was heraldry, a display of one's family name and history.

Societal recognition

Status symbols also indicate the cultural values of a society or a subculture. For example, in a commercial society, having money or wealth and things that can be bought by wealth, such as cars, houses, or fine clothing, are considered status symbols. Where warriors are respected, a scar can represent honor or courage.[3] Among intellectuals being able to think in an intelligent and educated way is an important status symbol regardless of material possessions. In academic circles, a long list of publications and a securely tenured position at a prestigious university or research institute are a mark of high status. It has been speculated that the earliest foods to be domesticated were luxury feast foods used to cement one's place as a "rich person".[4]

A uniform symbolizes membership in an organization, and may display additional insignia of rank, specialty, tenure and other details of the wearer's status within the organization. A state may confer decorations, medals or badges that can show that the wearer has heroic or official status. Elaborate color-coded academic regalia is often worn during commencement ceremonies, indicating academic rank and specialty.

In many cultures around the world, diverse visual markers of marital status are widely used. Coming of age rituals and other rites of passage may involve granting and display of symbols of a new status. Dress codes may specify who ought to wear particular kinds or styles of clothing, and when and where specific items of clothing are displayed.

Body modifications

The condition and appearance of one's body can be a status symbol. In times past, when most workers did physical labor outdoors under the sun and often had little food, being pale and fat was a status symbol, indicating wealth and prosperity (through having more than enough food and not having to do manual labor). Now that workers usually do less-physical work indoors and find little time for exercise, being tanned and thin is often a status symbol in modern cultures.

Dieting to reduce excess body fat is widely practiced in Western society, while some traditional societies still value obesity as a sign of prosperity. Development of muscles through exercise, previously disdained as a stigma of doing heavy manual labor, is now valued as a sign of personal achievement. Some groups, such as extreme bodybuilders and sumo wrestlers use special exercise and diet to "bulk up" into an impressive appearance.

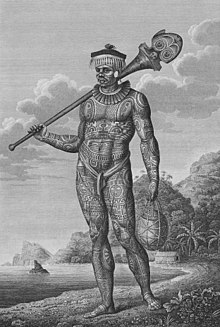

Warrior tattoos

Ancient Central American Maya cultures artificially induced crosseyedness and flattened the foreheads of high-born infants as a permanent, lifetime sign of noble status.[5] The Mayans also filed their teeth to sharp points to look fierce, or inset precious stones into their teeth as decoration.[5]

Material possessions

Hunting trophy of an aristocrat

Luxury goods are often perceived as status symbols. Examples may include a mansion or penthouse apartment,[6] a trophy spouse,[7]haute couture fashionable clothes,[8]jewellery,[9] or a luxury vehicle.[10] A sizeable collection of high-priced artworks or antiques may be displayed, sometimes in multiple seasonally occupied residences located around the world. Privately owned aircraft and luxury yachts are movable status symbols that can be taken from one glamorous location to another; the "jet set" refers to wealthy individuals who travel by private jet and who frequent fashionable resorts.[11]

Personal library of a wealthy American, 1919

Status symbols are also used by persons of much more modest means. In the Soviet Union before the fall of the Berlin Wall, possession of American-style blue jeans or rock music recordings (even pirated or bootlegged copies) was an important status symbol among rebellious teenagers. In the 1990s, foreign cigarettes in China, where a pack of Marlboro could cost one day's salary for some workers, were seen as a status symbol.[12]Mobile phone usage had been considered a status symbol (for example in Turkey in the early 1990s),[13] but is less distinctive today, because of the spread of inexpensive mobile phones. Nonetheless Apple products such as iPod or iPhone are common status symbols among modern teenagers.[14][15]

A common type of modern status symbol is a prestigious luxury branded item, whether apparel or other type of a good.[8] The brand name or logo is often prominently displayed, or featured as a graphic design element of decoration. Certain brands are so highly valued that cheap counterfeit goods or knock-off copies are purchased and displayed by those who do not want to, or are unable to, pay for the genuine item.

See also

- Badge of shame

- Conspicuous consumption

- Fashion accessory

- Narcissistic supply

- Positional good

- Social stratification

- Veblen good

References

^ Cherrington, David J. (1994). Organizational Behavior. Allyn and Bacon. p. 384. ISBN 0-205-15550-2..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ The Three Sociological Paradigms[dead link], from The HCC-Southwest College Archived 2004-08-05 at the Wayback Machine, December 2008.

^ "Real Men Have Dueling Scars". Stuff You Missed in History Class. 2009-05-04. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

^ Hayden B 2003. Were luxury foods the first domesticates? Ethnoarchaeological perspectives from Southeast Asia. World Archaeology 34(3)

^ ab "Maya Culture". Guatemala: Cradle of the Mayan Civilization. authenticmaya.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-07. Retrieved 2012-04-13.

^ Winter, Ian C. (1995). The Radical Home Owner. Taylor & Francis. p. 47. ISBN 2-88449-028-0.

^ Hill, Marcia; Esther D. Rothblum (1996). Classism and Feminist Therapy: Counting Costs. Haworth Press. p. 79. ISBN 1-56024-801-7.

^ ab Donna D. Heckler; Brian D. Till (10 October 2008). The Truth About Creating Brands People Love. FT Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-13-270118-1. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

^ Rebecca Ross Russell (5 June 2010). Gender and Jewelry: A Feminist Analysis. Rebecca Ross Russell. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4528-8253-6. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

^ Murray, Geoffrey (1994). Doing Business in China: The Last Great Market. China Library. ISBN 1-873410-28-X.

^ Merriam-Webster. Jet set. Accessed 2013-10-02.

^ J Brooks. American cigarettes have become a status symbol in smoke-saturated China. 1995.

^ Yusuf Ziya Özcan, Abdullah Koçak. Research Note: A Need or a Status Symbol? 2003

^ Alexander Greyling. Face your brand! The visual language of branding explained. Alex Greyling. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-620-44310-4. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

^ Said Baaghil (9 January 2013). Glamour Globals: Trends Over Brands. iUniverse. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4759-7167-5. Retrieved 10 September 2013.