Vandals

Vandalic goldfoil jewellery from the 3rd or 4th century

The Vandals were a large East Germanic tribe or group of tribes that first appear in history inhabiting present-day southern Poland. Some later moved in large numbers, including most notably the group which successively established kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula and then North Africa in the 5th century.[1]

The traditional view has been that the Vandals migrated from southern Scandinavia to the area between the lower Oder and Vistula rivers during the 2nd century BC and settled in Silesia from around 120 BC.[2][3][4] They are associated with the Przeworsk culture and were possibly the same people as the Lugii. Expanding into Dacia during the Marcomannic Wars and to Pannonia during the Crisis of the Third Century, the Vandals were confined to Pannonia by the Goths around 330 AD, where they received permission to settle from Constantine the Great. Around 400, raids by the Huns forced many Germanic tribes to migrate into the territory of the Roman Empire, and fearing that they might be targeted next the Vandals were pushed westwards, crossing the Rhine into Gaul along with other tribes in 406.[5] In 409 the Vandals crossed the Pyrenees into the Iberian Peninsula, where their main groups, the Hasdingi and the Silingi, settled in Gallaecia (northwest Iberia) and Baetica (south-central Iberia) respectively.[6]

After the Visigoths invaded Iberia in 418, the Iranian Alans and Silingi Vandals voluntarily subjected themselves to the rule of Hasdingian leader Gunderic, who was pushed from Gallaecia to Baetica by a Roman-Suebi coalition in 419. In 429, under king Genseric (reigned 428–477), the Vandals entered North Africa. By 439 they established a kingdom which included the Roman province of Africa as well as Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, Malta and the Balearic Islands. They fended off several Roman attempts to recapture the African province, and sacked the city of Rome in 455. Their kingdom collapsed in the Vandalic War of 533–4, in which Emperor Justinian I's forces reconquered the province for the Eastern Roman Empire.

Renaissance and early-modern writers characterized the Vandals as barbarians, "sacking and looting" Rome. This led to the use of the term "vandalism" to describe any pointless destruction, particularly the "barbarian" defacing of artwork. However, modern historians tend to regard the Vandals during the transitional period from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages as perpetuators, not destroyers, of Roman culture.[7]

Contents

1 Name

2 History

2.1 Origins

2.2 Introduction into the Roman Empire

2.3 In Gaul

2.4 In Hispania

2.5 Kingdom in North Africa

2.5.1 Establishment

2.5.2 Sack of Rome

2.5.3 Consolidation

2.5.4 Domestic religious tensions

2.5.5 Decline

2.5.6 Turbulent end

3 Physical appearance

4 List of kings

5 Language

6 Legacy

7 See also

8 References

9 Bibliography

10 Further reading

11 External links

Name

Neck ring with plug clasp from the Vandalic Treasure of Osztrópataka displayed at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria.

The name of the Vandals has often been connected to that of Vendel, the name of a province in Uppland, Sweden, which is also eponymous of the Vendel Period of Swedish prehistory, corresponding to the late Germanic Iron Age leading up to the Viking Age. The connection would be that Vendel is the original homeland of the Vandals prior to the Migration Period, and retains their tribal name as a toponym. Further possible homelands of the Vandals in Scandinavia are Vendsyssel in Denmark and Hallingdal in Norway.[8][self-published source]

The etymology of the name may be related to a Germanic verb *wand- "to wander" (English wend, German wandeln). The Germanic mythological figure of Aurvandil "shining wanderer; dawn wanderer, evening star", or "Shining Vandal" is reported as one of the "Germanic Dioscuri". R. Much has forwarded the theory that the tribal name Vandal reflects worship of Aurvandil or "the Dioscuri", probably involving an origin myth that the Vandalic kings were descended from Aurvandil (comparable to the case of many other Germanic tribal names).[9]

Some medieval authors applied the ethnonym "Vandals" to Slavs: Veneti, Wends, Lusatians or Poles.[10][11][12] It was once thought that the Slovenes were the descendants of the Vandals, but this is not the view of modern scholars.[13]

History

Origins

Germanic and Proto-Slavic tribes of Central Europe around 3rd century BC.

Tribes of Central Europe in the mid-1st century AD. The Vandals/Lugii are depicted in green, in the area of modern Poland.

Both Jordanes in his Getica and the Gotlandic Gutasaga tell that the Goths and Vandals migrated from southern Scandinavia[2][3][4] to the area between the lower Oder and Vistula prior to the 2nd century BC, and settled in Silesia from around 120 BC.[4] The earliest mention of the Vandals is from Pliny the Elder, who used the term Vandilii in a broad way to define one of the major groupings of all Germanic peoples. Tribes within this category who he mentions are the Burgundiones, Varini, Carini (otherwise unknown), and the Gutones.[14] According to the Gallaecian Christian priest, historian and theologian Paulus Orosius, the Vandals, who lived originally in Scoringa, near Stockholm, Sweden, were of the same stock as the Suiones ("Swedes") and the Goths.[15]

The Vandals are associated with the Przeworsk culture, but the culture probably extended over several eastern European peoples. Their origin, ethnicity and linguistic affiliation are heavily debated.[16][4][17][18] The bearers of the Przeworsk culture mainly practiced cremation and occasionally inhumation.[18] The Lugii (Lygier, Lugier or Lygians) are identified by modern historians as the same people as the Vandals.[4][4][19][20][21] The Lugii are mentioned by Strabo, Tacitus and Ptolemy as a large group of tribes between the Vistula and the Oder. None of those authors mentions the Vandals, while Pliny the Elder mentions the Vandals but not the Lugii.[17] According to John Anderson, the "Lugii and Vandili are designations of the same tribal group, the latter an extended ethnic name, the former probably a cult-title."[19]Herwig Wolfram notes that "In all likelihood the Lugians and the Vandals were one cultic community that lived in the same region of the Oder in Silesia, where it was first under Celtic and then under Germanic domination."[20]

Introduction into the Roman Empire

The Roman empire under Hadrian (ruled 117–38), showing the location of the Vandilii East Germanic tribes, then inhabiting the upper Vistula region (Poland).

By the end of the 2nd century, the Vandals were divided in two main tribal groups, the Silingi and the Hasdingi, with the Silingi being associated with Silesia and the Hasdingi living in the Sudetes. Around the mid 2nd century AD, there was a significant migration by Germanic tribes of Scandinavian origin (Rugii, Goths, Gepidae, Vandals, Burgundians, and others)[22] towards the south-east, creating turmoil along the entire Roman frontier.[22][23][24][25] The 6th century Byzantine historian Procopius noted that the Goths, Gepidae and Vandals were physically and culturally identical, suggesting a common origin.[26] These migrations culminated in the Marcomannic Wars, which resulted in widespread destruction and the first invasion of Italy in the Roman Empire period.[25] During the Marcomannic Wars (166–180) the Hasdingi (or Astingi), led by the kings Raus and Rapt (or Rhaus and Raptus) moved south, entering Dacia as allies of Rome.[27] However they eventually caused problems in Dacia and moved further south, towards the lower Danube area. Together with the Hasdingi were the Lacringi, who were possibly also Vandals.[28][29] In about 271 AD the Roman Emperor Aurelian was obliged to protect the middle course of the Danube against them. They made peace and stayed on the eastern bank of the Danube.[27]

Reconstruction of an Iron Age warrior's garments representing a Vandalic man, with his hair in a "Suebian knot" (160 AD), Archaeological Museum of Kraków, Poland.

According to Jordanes' Getica, the Hasdingi came into conflict with the Goths around the time of Constantine the Great. At the time, the Vandals were living in lands later inhabited by the Gepids, where they were surrounded "on the east [by] the Goths, on the west [by] the Marcomanni, on the north [by] the Hermanduri and on the south [by] the Hister (Danube)." The Vandals were attacked by the Gothic king Geberic, and their king Visimar was killed.[30] The Vandals then migrated to Pannonia, where, after Constantine the Great (in about 330) granted them lands on the right bank of the Danube, they lived for the next sixty years.[30][31]

Around this time, the Hasdingi had already been Christianized. During the Emperor Valens's reign (364–78) the Vandals accepted, much like the Goths earlier, Arianism, a belief that was in opposition to that of the Nicene orthodoxy of the Roman Empire.[30] Yet there were also some scattered orthodox Vandals, among whom was the famous magister militum Stilicho, the chief minister of the Emperor Honorius probably more due to Stilicho being half Vandal and half Roman.

In 400 or 401, Hunnic raids forced many Germanic tribes such as the Goths to migrate Westward. Worried that they might be targeted next by the Huns, the Vandals under king Godigisel, along with their allies (the Iranian Alans and Germanic Suebians), moved westwards into Roman territory.[5] Some of the Silingi joined them later. Vandals raided the Roman province of Raetia in the winter of 401/402. From this, historian Peter Heather concludes that at this time the Vandals were located in the region around the Middle and Upper Danube.[32] It is possible that the Vandals were part of the Gothic king Radagaisus' invasion of Italy in 405–406 AD.[33]

In Gaul

In 406 the Vandals advanced from Pannonia travelling west along the Danube without much difficulty, but when they reached the Rhine, they met resistance from the Franks, who populated and controlled Romanized regions in northern Gaul. Twenty thousand Vandals, including Godigisel himself, died in the resulting battle, but then with the help of the Alans they managed to defeat the Franks, and on December 31, 406 the Vandals crossed the Rhine, probably while it was frozen, to invade Gaul, which they devastated terribly. Under Godigisel's son Gunderic, the Vandals plundered their way westward and southward through Aquitaine.

In Hispania

Migrations of the Vandals from Scandinavia through Dacia, Gaul, Iberia, and into North Africa. Grey: Roman Empire.

On October 13, 409 they crossed the Pyrenees into the Iberian peninsula. There, the Hasdingi received land from the Romans, as foederati, in Asturia (Northwest) and the Silingi in Hispania Baetica (South), while the Alans got lands in Lusitania (West) and the region around Carthago Nova.[6] The Suebi also controlled part of Gallaecia. The Visigoths, who invaded Iberia before receiving lands in Septimania (Southern France), crushed the Alans in 418, killing the western Alan king Attaces.[34] The remainder of his people and the remnants of the Silingi, who were nearly wiped out, subsequently appealed to the Vandal king Gunderic to accept the Alan crown. Later Vandal kings in North Africa styled themselves Rex Wandalorum et Alanorum ("King of the Vandals and Alans"). In 419 AD the Hasdingi Vandals were defeated by a joint Roman-Suebi coalition. Gunderic fled to Baetica, where he was also proclaimed king of the Silingi Vandals.[4] In 422 Gunderic decisively defeated a Roman-Suebi-Gothic coalition led by the Roman patrician Castinus at the Battle of Tarraco.[35][36][37] It is likely that many Roman and Gothic troops deserted to Gunderic following the battle.[37] For the next five years, according to Hydatius, Gunderic created widespread havoc in the western Mediterranean.[37] In 425, the Vandals pillaged the Balearic Islands, Hispania and Mauritania, sacking Carthago Spartaria (Cartagena) and Hispalis (Seville).[37] The capture of the maritime city of Carthago Spartaria enabled the Vandals to engage in widespread naval activities.[37] In 428 Gunderic captured Hispalis but died while laying siege to the city's church.[37] He was succeeded by his half-brother Genseric, who although he was illegitimate (his mother was a Roman slave) had held a prominent position at the Vandal court, rising to the throne unchallenged.[38]

Genseric is often regarded by historians as the most able barbarian leader of the Migration Period.[39] Michael Frasseto writes that he probably contributed more to the destruction of Rome than any of his contemporaries.[39] Although the barbarians controlled Hispania they still comprised a tiny minority among a much larger Hispano-Roman population, approximately 200,000 out of 6,000,000.[6] Shortly after seizing the throne, Genseric was attacked from the rear by a large force of Suebi under the command of Heremigarius who had managed to take Lusitania.[40] This Suebi army was defeated near Mérida and its leader Hermigario drowned in the Guadiana River while trying to flee.[40]

It is possible that the name Al-Andalus (and its derivative Andalusia) is derived from the Arabic adoption of the name of the Vandals.[41][42]

Kingdom in North Africa

Establishment

The Vandal Kingdom at its greatest extent in the 470s

Coin of Bonifacius Comes Africae (422–431 CE), who was defeated by the Vandals.[43]

The Vandals under Genseric (also known as Geiseric) crossed to Africa in 429.[44] Although numbers are unknown and some historians debate the validity of estimates, based on Procopius' assertion that the Vandals and Alans numbered 80,000 when they moved to North Africa,[45] Peter Heather estimates that they could have fielded an army of around 15,000–20,000.[46]

According to Procopius, the Vandals came to Africa at the request of Bonifacius, the military ruler of the region.[47] Seeking to establish himself as an independent ruler in Africa or even become Roman Emperor, Bonifacius had defeated several Roman attempts to subdue him, until he was mastered by the newly appointed Gothic count of Africa, Sigisvult, who captured both Hippo Regius and Carthage.[39] It is possible that Bonifacius had sought Genseric as an ally against Sigisvult, promising him a part of Africa in return.[39]

Advancing eastwards along the coast, the Vandals were confronted on the Numidian border in May–June 430 by Bonifacius. Negotiations broke down, and Bonifacius was soundly defeated.[48][49] Bonifacius subsequently barricaded himself inside Hippo Regius with the Vandals besieging the city.[44] Inside, Saint Augustine and his priests prayed for relief from the invaders, knowing full well that the fall of the city would spell conversion or death for many Roman Christians.[citation needed]

On 28 August 430, three months into the siege, St. Augustine (who was 75 years old) died,[50] perhaps from starvation or stress, as the wheat fields outside the city lay dormant and unharvested. The death of Augustine shocked the Regent of the Western Roman Empire, Galla Placidia, who feared the consequences if her realm lost its most important source of grain.[49] She raised a new army in Italy and convinced her nephew in Constantinople, the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II, to send an army to North Africa led by Aspar.[49]

Around July–August 431, Genseric raised the siege of Hippo Regius,[48] which enabled Bonifacius to retreat from Hippo Regius to Carthage, where he was joined by Aspar's army. Some time in the summer of 432, Genseric soundly defeated the joint forces of both Bonifacius and Aspar, which enabled him to seize Hippo Regius unopposed.[49] Genseric and Aspar subsequently negotiated a peace treaty of some sorts.[48] Upon seizing Hippo Regius, Genseric made it the first capital of the Vandal kingdom.[51]

The Romans and the Vandals concluded a treaty in 435 giving the Vandals control of coastal Numidia. Genseric chose to break the treaty in 439 when he invaded the province of Africa Proconsularis and seized Carthage on October 19.[52] The city was captured without a fight; the Vandals entered the city while most of the inhabitants were attending the races at the hippodrome. Genseric made it his capital, and styled himself the King of the Vandals and Alans, to denote the inclusion of the Alans of northern Africa into his alliance.[citation needed] His forces occupied Sardinia, Corsica and the Balearic Islands, he built his kingdom into a powerful state. His siege of Palermo in 440 was a failure as was the second attempt to invade Sicily near Agrigento in 442 (the Vandals occupied the island from 468-476 when it was ceded to Odovacer).[53] Historian Cameron suggests that the new Vandal rule may not have been unwelcomed by the population of North Africa as the great landowners were generally unpopular.[54]

The impression given by ancient sources such as Victor of Vita, Quodvultdeus, and Fulgentius of Ruspe was that the Vandal take-over of Carthage and North Africa led to widespread destruction. However, recent archaeological investigations have challenged this assertion. Although Carthage's Odeon was destroyed, the street pattern remained the same and some public buildings were renovated. The political centre of Carthage was the Byrsa Hill. New industrial centres emerged within towns during this period.[55] Historian Andy Merrills uses the large amounts of African Red Slip ware discovered across the Mediterranean dating from the Vandal period of North Africa to challenge the assumption that the Vandal rule of North Africa was a time of economic instability.[56] When the Vandals raided Sicily in 440, the Western Roman Empire was too preoccupied with war with Gaul to react. Theodosius II, emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, dispatched an expedition to deal with the Vandals in 441; however, it only progressed as far as Sicily. The Western Empire under Valentinian III secured peace with the Vandals in 442.[57] Under the treaty the Vandals gained Byzacena, Tripolitania, and part of Numidia, and confirmed their control of Proconsular Africa[58] as well as the Vandal Kingdom as the first barbarian state officially recognized as an independent kingdom in former Roman territory instead of foederati.[59] The Empire regained western Numidia and the two Mauretanian provinces until 455.

Sack of Rome

The Sack of Rome, Karl Briullov, 1833–1836

During the next thirty-five years, with a large fleet, Genseric looted the coasts of the Eastern and Western Empires. Vandal activity in the Mediterranean was so substantial that the sea's name in Old English was Wendelsæ (i. e. Sea of the Vandals).[60] After Attila the Hun's death, however, the Romans could afford to turn their attention back to the Vandals, who were in control of some of the richest lands of their former empire.

In an effort to bring the Vandals into the fold of the Empire, Valentinian III offered his daughter's hand in marriage to Genseric's son. Before this treaty could be carried out, however, politics again played a crucial part in the blunders of Rome. Petronius Maximus killed Valentinian III and claimed the Western throne. Diplomacy between the two factions broke down, and in 455 with a letter from the Empress Licinia Eudoxia, begging Genseric's son to rescue her, the Vandals took Rome, along with the Empress and her daughters Eudocia and Placidia.

The chronicler Prosper of Aquitaine[61] offers the only fifth-century report that, on 2 June 455, Pope Leo the Great received Genseric and implored him to abstain from murder and destruction by fire, and to be satisfied with pillage. Whether the pope's influence saved Rome is, however, questioned. The Vandals departed with countless valuables. Eudoxia and her daughter Eudocia were taken to North Africa.[58]

Consolidation

In 456 a Vandal fleet of 60 ships threatening both Gaul and Italy was ambushed and defeated at Agrigentum and Corsica by the Western Roman general Ricimer.[62] In 457 a mixed Vandal-Berber army returning with loot from a raid in Campania were soundly defeated in a surprise attack by Western Emperor Majorian at the mouth of the Garigliano river.[63]

As a result of the Vandal sack of Rome and piracy in the Mediterranean, it became important to the Roman Empire to destroy the Vandal kingdom. In 460, Majorian launched an expedition against the Vandals, but was defeated at the Battle of Cartagena. In 468 the Western and Eastern Roman empires launched an enormous expedition against the Vandals under the command of Basiliscus, which reportedly was composed of 100,000 soldiers and 1,000 ships. The Vandals defeated the invaders at the Battle of Cap Bon, capturing the Western fleet, and destroying the Eastern through the use of fire ships.[57] Following up the attack, the Vandals tried to invade the Peloponnese, but were driven back by the Maniots at Kenipolis with heavy losses.[64] In retaliation, the Vandals took 500 hostages at Zakynthos, hacked them to pieces and threw the pieces overboard on the way to Carthage.[64]

In the 470s, the Romans abandoned their policy of war against the Vandals. The Western general Ricimer reached a treaty with them,[57] and in 476 Genseric was able to conclude a "perpetual peace" with Constantinople. Relations between the two states assumed a veneer of normality.[65] From 477 onwards, the Vandals produced their own coinage, restricted to bronze and silver low-denomination coins. The high-denomination imperial money was retained, demonstrating in the words of Merrills "reluctance to usurp the imperial prerogative".[66]

Although the Vandals had fended off attacks from the Romans and established hegemony over the islands of the western Mediterranean, they were less successful in their conflict with the Berbers. Situated south of the Vandal kingdom, the Berbers inflicted two major defeats on the Vandals in the period 496–530.[57]

Domestic religious tensions

A denarius of the reign of Hilderic

Differences between the Arian Vandals and their Trinitarian subjects (including both Catholics and Donatists) were a constant source of tension in their African state. Catholic bishops were exiled or killed by Genseric and laymen were excluded from office and frequently suffered confiscation of their property.[67] He protected his Catholic subjects when his relations with Rome and Constantinople were friendly, as during the years 454–57, when the Catholic community at Carthage, being without a head, elected Deogratias bishop. The same was also the case during the years 476–477 when Bishop Victor of Cartenna sent him, during a period of peace, a sharp refutation of Arianism and suffered no punishment.[citation needed] Huneric, Genseric's successor, issued edicts against Catholics in 483 and 484 in an effort to marginalise them and make Arianism the primary religion in North Africa.[68] Generally most Vandal kings, except Hilderic, persecuted Trinitarian Christians to a greater or lesser extent, banning conversion for Vandals, exiling bishops and generally making life difficult for Trinitarians.[citation needed]

Decline

According to the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia: "Genseric, one of the most powerful personalities of the "era of the Migrations", died on 25 January 477, at the great age of around 88 years. According to the law of succession which he had promulgated, the oldest male member of the royal house was to succeed. Thus he was succeeded by his son Huneric (477–484), who at first tolerated Catholics, owing to his fear of Constantinople, but after 482 began to persecute Manichaeans and Catholics."[69]

Gunthamund (484–496), his cousin and successor, sought internal peace with the Catholics and ceased persecution once more. Externally, the Vandal power had been declining since Genseric's death, and Gunthamund lost early in his reign all but a small wedge of western Sicily to the Ostrogoths and had to withstand increasing pressure from the autochthonous Moors.

According to the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia: "While Thrasamund (496–523), owing to his religious fanaticism, was hostile to Catholics, he contented himself with bloodless persecutions".[69]

Turbulent end

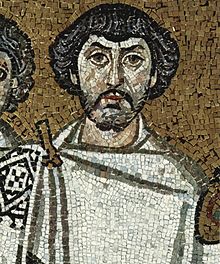

Belisarius may be this bearded figure on the right of Emperor Justinian I in the mosaic in the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, which celebrates the reconquest of Italy by the Byzantine army under the skillful leadership of Belisarius

Hilderic (523–530) was the Vandal king most tolerant towards the Catholic Church. He granted it religious freedom; consequently Catholic synods were once more held in North Africa. However, he had little interest in war, and left it to a family member, Hoamer. When Hoamer suffered a defeat against the Moors, the Arian faction within the royal family led a revolt, raising the banner of national Arianism, and his cousin Gelimer (530–533) became king. Hilderic, Hoamer and their relatives were thrown into prison.[70]

Byzantine Emperor Justinian I declared war, with the stated intention of restoring Hilderic to the Vandal throne. The deposed Hilderic was murdered in 533 on Gelimer's orders.[70] While an expedition was en route, a large part of the Vandal army and navy was led by Tzazo, Gelimer's brother, to Sardinia to deal with a rebellion. As a result, the armies of the Byzantine Empire commanded by Belisarius were able to land unopposed 10 miles (16 km) from Carthage. Gelimer quickly assembled an army,[71] and met Belisarius at the Battle of Ad Decimum; the Vandals were winning the battle until Gelimer's brother Ammatas and nephew Gibamund fell in battle. Gelimer then lost heart and fled. Belisarius quickly took Carthage while the surviving Vandals fought on.[72]

On December 15, 533, Gelimer and Belisarius clashed again at the Battle of Tricamarum, some 20 miles (32 km) from Carthage. Again, the Vandals fought well but broke, this time when Gelimer's brother Tzazo fell in battle. Belisarius quickly advanced to Hippo, second city of the Vandal Kingdom, and in 534 Gelimer surrendered to the Byzantine conqueror, ending the Kingdom of the Vandals.

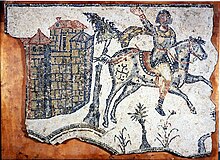

Vandal cavalryman, c. AD 500, from a mosaic pavement at Bordj Djedid near Carthage

North Africa, comprising north Tunisia and eastern Algeria in the Vandal period, became a Roman province again, from which the Vandals were expelled. Many Vandals went to Saldae (today called Béjaïa in north Algeria) where they integrated themselves with the Berbers. Many others were put into imperial service or fled to the two Gothic kingdoms (Ostrogothic Kingdom and Visigothic Kingdom). Some Vandal women married Byzantine soldiers and settled in north Algeria and Tunisia. The choicest Vandal warriors were formed into five cavalry regiments, known as Vandali Iustiniani, stationed on the Persian frontier. Some entered the private service of Belisarius.[73] The 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia states that "Gelimer was honourably treated and received large estates in Galatia. He was also offered the rank of a patrician but had to refuse it because he was not willing to change his Arian faith".[69] In the words of historian Roger Collins: "The remaining Vandals were then shipped back to Constantinople to be absorbed into the imperial army. As a distinct ethnic unit they disappeared".[71] Some of the few Vandals remained at North Africa while more migrated back to Spain.[5] In 546 the Vandalic Dux of Numidia, Guntarith, defected from the Byzantines and raised a rebellion with Moorish support. He was able to capture Carthage, but was assassinated by the Byzantines shortly afterwards.

Physical appearance

The 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius wrote that the Vandals were tall and blond haired:

For they all have white bodies and fair hair, and are tall and handsome to look upon...[26]

List of kings

Known kings of the Vandals:[citation needed]

Wisimar (d.335)

Godigisel (359–406)

Gunderic (407–428)

Genseric (428–477)

Huneric (477–484)

Gunthamund (484–496)

Thrasamund (496–523)

Hilderic (523–530)

Gelimer (530–534)

Language

Very little is known about the Vandalic language itself, which was of the East Germanic linguistic branch. The Goths have left behind the only text corpus of the East Germanic language type: a 4th-century translation of the Gospels.[74] All Vandals that modern historians know about were able to speak Latin, which also remained the official language of the Vandal administration (most of the staff seems to have been native African/Roman).[75] Levels of literacy in the ancient world are uncertain, but writing was integral to administration and business. Studies of literacy in North Africa have tended to centre around the administration, which was limited to the social elite. However, the majority of the population of North Africa did not live in urban centres.[76]

Judith George explains that "Analysis of the [Vandal] poems in their context holds up a mirror to the ways and values of the times".[77] Very little work of the poets of Vandal North Africa survives, but what does is found in the Latin Anthology; apart from their names, little is known about the poets themselves, not even when they were writing. Their work drew on earlier Roman traditions. Modern scholars generally hold the view that the Vandals allowed the Romans in North Africa to carry on with their way of life with only occasional interference.[78]

Legacy

The Vandals' traditional reputation: a coloured steel engraving of the Sack of Rome (455) by Heinrich Leutemann (1824–1904), c. 1860–80

Since the Middle Ages, kings of Denmark were styled "King of Denmark, the Goths and the Wends", the Wends being a group of West Slavs formerly living in Mecklenburg and eastern Holstein in modern Germany. The title "King of the Wends" is translated as vandalorum rex in Latin. The title was shortened to "King of Denmark" in 1972.[79] Starting in 1540, Swedish kings (following Denmark) were styled Suecorum, Gothorum et Vandalorum Rex ("King of the Swedes, Geats, and Wends").[80]Carl XVI Gustaf dropped the title in 1973 and now styles himself simply as "King of Sweden".

The modern term vandalism stems from the Vandals' reputation as the barbarian people who sacked and looted Rome in AD 455. The Vandals were probably not any more destructive than other invaders of ancient times, but writers who idealized Rome often blamed them for its destruction. For example, English Enlightenment poet John Dryden wrote, Till Goths, and Vandals, a rude Northern race, / Did all the matchless Monuments deface.[81]

The term Vandalisme was coined in 1794 by Henri Grégoire, bishop of Blois, to describe the destruction of artwork following the French Revolution. The term was quickly adopted across Europe. This new use of the term was important in colouring the perception of the Vandals from later Late Antiquity, popularizing the pre-existing idea that they were a barbaric group with a taste for destruction. Vandals and other "barbarian" groups had long been blamed for the fall of the Roman Empire by writers and historians.[82]

Robin Hemley wrote a short story, "The Liberation of Rome," in which a professor of ancient history (mainly Roman) is confronted by a student claiming to be an ethnic Vandal.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vandals. |

- Aurvandil

- Migrations period

- Timeline of Germanic kingdoms

References

^ "Vandal". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 March 2014..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ ab "Germanic peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

[permanent dead link]

^ ab "History of Europe: Barbarian migrations and invasions: The Germans and Huns". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

^ abcdefg Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 821–825

^ abc Brian, Adam. "History of the Vandals". Roman Empire. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

^ abc "Spain: Visigothic Spain to c. 500". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

^

Contrasting articles in Frank M. Clover and R.S. Humphreys, eds, Tradition and Innovation in Late Antiquity (University of Wisconsin Press) 1989, highlight the Vandals' role as continuators: Frank Clover stresses continuities in North African Roman mosaics and coinage and literature, whereas Averil Cameron, drawing upon archaeology, documents how swift were the social, religious and linguistic changes once the area was conquered by Byzantium and then by Islam.

^ Ulwencreutz, Lars (2013). Ulwencreutz's The Royal Families in Europe V. Lulu.com. p. 408.

^ R. Much, Wandalische Götter, Mitteilungen der Schlesischen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde 27, 1926, 20–41. "R. Much has brought forth a relatively convincing argument to show that the very name Vandal reflects the worship of the Divine Twins." Donald Ward, The divine twins: an Indo-European myth in Germanic tradition, University of California publications: Folklore studies, nr. 19, 1968, p. 53.

^ Annales Alamannici, 795 ad

^ Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum by Adam Bremensis 1075 ad

^ Roland Steinacher under Reiner Protsch "Studien zur vandalischen Geschichte. Die Gleichsetzung der Ethnonyme Wenden, Slawen und Vandalen vom Mittelalter bis ins 18. Jahrhundert Archived 2007-01-19 at the Wayback Machine", 2002

^ Lenček, Rado L. (1990). "The Terms Wende-Winde, Wendisch-Windisch in the Historiographic Tradition of the Slovene Lands". Slovene Studies Journal. 12 (2). ISSN 0193-1075. Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

^ "Natural History 4.28". Archived from the original on 2013-05-30. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

^ Orosius (417). The Anglo-Saxon Version, from the Historian Orosius (Alfred the Great ed.). London: Printed by W. Bowyer and J. Nichols and sold by S. Baker. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

^ "Land and People, p.25" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2007. Retrieved July 30, 2005.

^ ab Merrils 2004, pp. 32–33

^ ab Todd 2009, p. 25

^ ab Anderson 1938, p. 198

^ ab Wolfram 1997, p. 42

^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 498

^ ab "History of Europe: The Germans and Huns". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

^ "Ancient Rome: The barbarian invasions". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

^ "Germanic peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 2013-11-20. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

^ ab "Germany: Ancient History". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 2013-08-28. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

^ ab Procopius. History of the Wars. Book III. II

^ ab Merrils & Miles 2010, p. 30

^ Dio Cassius, 72.12

^ Merrils & Miles 2010, p. 27

^ abc Schutte 2013, pp. 50–54

^ Jordanes chapter 22 Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine

^ Heather 2005, p. 195

^ Merrils & Miles 2010, p. 34

^ Vasconcellos 1913, p. 551

^ Jaques 2007

^ Jaques 2007, p. 999

^ abcdef Merrils & Mill 2010, p. 50

^ Merrils & Mills 2010, pp. 49–50

^ abcd Frasseto 2003, p. 173

^ ab Cossue (28 November 2005). "Breve historia del reino suevo de Gallaecia (1)". Celtiberia.net. Archived from the original on 2012-01-07. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

^ Mokhtar 1981, p. 281 (Volume 2)

^ Burke 1900, p. 410 (Volume 1)

^ "CNG Coins". Archived from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-08-10.

^ ab Collins 2000, p. 124

^ Procopius Wars 3.5.18–19 in Heather 2005, p. 512

^ Heather 2005, pp. 197–198

^ Procopius Wars 3.5.23–24 in Collins 2004, p. 124

^ abc Merrils & Mills 2010, pp. 53–55

^ abcd Reynolds, pp. 130–131

^ "Newadvent.org". Archived from the original on 2017-10-20. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

^ Merrils & Mills 2010, p. 60

^ Collins 2004, pp. 124–125

^ J.B. Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire, Dover Vol. I. pp. 254, 258, 410 Library of Congress Catalog Number -58-11273

^ Cameron 2000, pp. 553–554

^ Merrills 2004, p. 10

^ Merrills 2004, p. 11

^ abcd Collins 2000, p. 125

^ ab Cameron 2000, p. 553

^ Patout Burns, J.; Jensen, Robin M. (November 30, 2014). Christianity in Roman Africa: The Development of Its Practices and Beliefs– Google Knihy. ISBN 978-0-8028-6931-9. Archived from the original on 2016-12-26. Retrieved 2016-12-25.

^ "Mediterranean". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

^ Prosper's account of the event was followed by his continuator in the sixth century, Victor of Tunnuna, a great admirer of Leo quite willing to adjust a date or bend a point (Steven Muhlberger, "Prosper's Epitoma Chronicon: was there an edition of 443?" Classical Philology 81.3 (July 1986), pp 240–244).

^ Jaques 2007, p. 264

^ Jaques 2008, p. 383

^ ab Greenhalgh & Eliopoulos 1985, p. 21

^ Bury 1923, p. 125

^ Merrills 2004, pp. 11–12

^ Collins 2004, pp. 125–126

^ Cameron 2000, p. 555

^ abc Löffler 1912

^ ab Bury 1923, p. 131

^ ab Collins 2004, p. 126

^ Bury 1923, pp. 133–135

^ Bury 1923, pp. 124–150

^ Mallory & Adams 1997, pp. 217, 301

^ Wickham 2009, p. 77

^ Conant 2004, pp. 199–200

^ George 2004, p. 138

^ George 2004, pp. 138–139

^ Norman Berdichevsky (21 September 2011). An Introduction to Danish Culture. McFarland. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-7864-6401-2. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

^ J. Guinchard (1914). Sweden: Historical and statistical handbook. Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söner. p. 188. Archived from the original on 2013-05-26. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

^ Dryden, John, "To Sir Godfrey Kneller", 1694. Dryden also wrote of Renaissance Italy "reviving from the trance/Of Vandal, Goth and Monkish ignorance. ("To the Earl of Roscommon", 1680).

^ Merrills & Miles 2010, pp. 9–10

Bibliography

Anderson, John (1938). Germania. Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 978-1-85399-503-3. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

Burke, Ulick Ralph (1900), A History of Spain from the Earliest Times to the Death of Ferdinand the Catholic, 1, Year Books, p. 410, ISBN 978-1-4437-4054-8

Bury, John Bagnell (1923), History of the Later Roman Empire, from the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian (A.D.395 to A.D. 565). Volume II, Macmillan

Cameron, Averil (2000), "The Vandal conquest and Vandal rule (A.D. 429–534)", The Cambridge Ancient History. Late Antiquity: Empire and Successors, A.D. 425–600, XIV, Cambridge University Press, pp. 553–559

Collins, Roger (2000), "Vandal Africa, 429–533", The Cambridge Ancient History. Late Antiquity: Empire and Successors, A.D. 425–600, XIV, Cambridge University Press, pp. 124–126

Conant, Jonathan (2004), "Literacy and Private Documentation in Vandal North Africa: The Case of the Albertini Tablets", Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on Late Antique North Africa, Ashgate Publishing, pp. 199–224, ISBN 978-0-7546-4145-2

Frassetto, Michael (January 1, 2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576072639. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

George, Judith (2004), "Vandal Poets in their Context", Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on Late Antique North Africa, Ashgate Publishing, pp. 133–144, ISBN 978-0-7546-4145-2

Greenhalgh, P. A. L.; Eliopoulos, Edward (1985), Deep into Mani: Journey to the Southern Tip of Greece, Faber and Faber, ISBN 978-0-571-13523-3

Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A-E. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313335372. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

Jaques, Tony (2008). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313335389. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: P-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313335396. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

Heather, Peter (2005), The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-98914-2

Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (eds) (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Merrills, Andy (2004), "Vandals, Romans and Berbers: Understanding Late Antique North Africa", Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on Late Antique North Africa, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-4145-2

Merrills, Andy; Miles, Richard (2010), The Vandals, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-4051-6068-1

Mokhtar, G (1981), Ancient Civilizations of Africa, 2, University of California Press, p. 281, ISBN 978-0-520-06697-7

Reynolds, Julian (2011-06-25). Defending Rome: The Masters of the Soldiers. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1477164600. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

[self-published source]

Schutte, Gudmund (2013). Our Forefathers, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-67723-4. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

Todd, Malcolm (2009). The Early Germans. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-3756-0. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

Vasconcellos, José Leite (1913), Religiões da Lusitania na parte que principalmente se refere a Portugal, 3, Imprensa Nacional

Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-2918-1. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

Wickham, Chris (2009), The Inheritance of Rome, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0

Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and its Germanic peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08511-4. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Löffler, Klemens (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 15. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Löffler, Klemens (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 15. New York: Robert Appleton.

Further reading

- Blume, Mary. "Vandals Exhibit Sacks Some Cultural Myths", International Herald Tribune, August 25, 2001.

- Christian Courtois: Les Vandales et l'Afrique. Paris 1955

- Clover, Frank M: The Late Roman West and the Vandals. Aldershot 1993 (Collected studies series 401),

ISBN 0-86078-354-5 - Die Vandalen: die Könige, die Eliten, die Krieger, die Handwerker. Publikation zur Ausstellung "Die Vandalen"; eine Ausstellung der Maria-Curie-Sklodowska-Universität Lublin und des Landesmuseums Zamość ... ; Ausstellung im Weserrenaissance-Schloss Bevern ... Nordstemmen 2003.

ISBN 3-9805898-6-2

John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries- F. Papencordt's Geschichte der vandalischen Herrschaft in Afrika

- Guido M. Berndt, Konflikt und Anpassung: Studien zu Migration und Ethnogenese der Vandalen (Historische Studien 489, Husum 2007),

ISBN 978-3-7868-1489-4. - Hans-Joachim Diesner: Vandalen. In: Paulys Realencyclopädie der class. Altertumswissenschaft (RE Suppl. X, 1965), S. 957–992.

- Hans-Joachim Diesner: Das Vandalenreich. Aufstieg und Untergang. Stuttgart 1966. 5.

- Helmut Castritius: Die Vandalen. Etappen einer Spurensuche. Stuttgart u.a. 2007.

- Ivor J. Davidson, A Public Faith, Chapter 11, Christians and Barbarians, Volume 2 of Baker History of the Church, 2005,

ISBN 0-8010-1275-9 - L'Afrique vandale et Byzantine. Teil 1. Turnhout 2002 (Antiquité Tardive 10),

ISBN 2-503-51275-5. - L'Afrique vandale et Byzantine. Teil 2, Turnhout 2003 (Antiquité Tardive 11),

ISBN 2-503-52262-9. - Lord Mahon Philip Henry Stanhope, 5th Earl Stanhope, The Life of Belisarius, 1848. Reprinted 2006 (unabridged with editorial comments) Evolution Publishing,

ISBN 1-889758-67-1. Evolpub.com - Ludwig Schmidt: Geschichte der Wandalen. 2. Auflage, München 1942.

- Pauly-Wissowa

- Pierre Courcelle: Histoire littéraire des grandes invasions germaniques. 3rd edition Paris 1964 (Collection des études Augustiniennes: Série antiquité, 19).

- Roland Steinacher: Vandalen – Rezeptions- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte. In: Hubert Cancik (Hrsg.): Der Neue Pauly, Stuttgart 2003, Band 15/3, S. 942–946,

ISBN 3-476-01489-4. - Roland Steinacher: Wenden, Slawen, Vandalen. Eine frühmittelalterliche pseudologische Gleichsetzung und ihr Nachleben bis ins 18. Jahrhundert. In: W. Pohl (Hrsg.): Auf der Suche nach den Ursprüngen. Von der Bedeutung des frühen Mittelalters (Forschungen zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 8), Wien 2004, S. 329–353. Uibk.ac.at

- Stefan Donecker; Roland Steinacher, Rex Vandalorum – The Debates on Wends and Vandals in Swedish Humanism as an Indicator for Early Modern Patterns of Ethnic Perception, in: ed. Robert Nedoma, Der Norden im Ausland – das Ausland im Norden. Formung und Transformation von Konzepten und Bildern des Anderen vom Mittelalter bis heute (Wiener Studien zur Skandinavistik 15, Wien 2006) 242–252. Uibk.ac.at

- Victor of Vita, History of the Vandal Persecution

ISBN 0-85323-127-3. Written 484. - Walter Pohl: Die Völkerwanderung. Eroberung und Integration. Stuttgart 2002, S. 70–86,

ISBN 3-17-015566-0. - Westermann, Grosser Atlas zur Weltgeschichte (in German)

Yves Modéran: Les Maures et l'Afrique romaine. 4e.-7e. siècle. Rom 2003 (Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises d'Athènes et de Rome, 314),

ISBN 2-7283-0640-0.- Robert Kasperski, Ethnicity, ethnogenesis, and the Vandals: Some Remarks on a Theory of Emergence of the Barbarian Gens, „Acta Poloniae Historia” 112, 2015, pp. 201–242.

External links

| Look up Vandals in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up vandal in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Kingdom of the Vandals – location map