Brownsville, Pennsylvania

Brownsville, Pennsylvania | |

|---|---|

Borough | |

View of Brownsville from across the Monongahela River | |

| Etymology: Thomas Brown | |

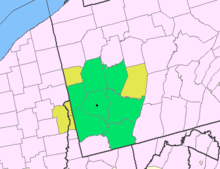

Location of Brownsville in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. | |

Brownsville Location of Brownsville in Pennsylvania | |

| Coordinates: 40°1′12″N 79°53′22″W / 40.02000°N 79.88944°W / 40.02000; -79.88944Coordinates: 40°1′12″N 79°53′22″W / 40.02000°N 79.88944°W / 40.02000; -79.88944 | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Fayette |

| Established | 1785 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ross H Swords, Jr. |

| Area [1] | |

| • Total | 1.09 sq mi (2.83 km2) |

| • Land | 0.98 sq mi (2.53 km2) |

| • Water | 0.11 sq mi (0.30 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 2,331 |

| • Estimate (2016)[2] | 2,270 |

| • Density | 2,323.44/sq mi (897.19/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 15417 |

| Area code(s) | 724 |

| FIPS code | 42-09432 |

GNIS feature ID | 1214026 |

| Website | brownsvilleborough.com |

Brownsville is a borough in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, United States, first settled in 1785 as the site of a trading post a few years after the pacification of the Iroquois enabled a post-Revolutionary war resumption of westward migration. The Trading Post soon became a tavern and Inn, and was soon receiving emigrants heading west as it was located above the cut bank overlooking first ford that could be reached to those descending from the Mountains[a] Brownsville is located 40 miles (64 km) south of Pittsburgh along the east bank of the Monongahela River.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the borough of Brownsville, located as a county border town has a total area of 1.1 square miles (2.8 km2), of which 0.97 square miles (2.5 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.3 km2), or 10.47%, is water[3]—most of which is the Fayette County half of the Monongahela River between the community and the flatter lands of opposite shore West Brownsville in Washington County. As a community, the town is the central population center for a number of outlying hamlets geographically tied to the town for the same reasons they were founded nearby—Western Pennsylvania has far more hills and steep slopes than flats or gentle sloping terrains suitable for settlement. This keeps Brownsville at the nexus of the transportation infrastructure which grew up during its history. While no longer a passenger depot, the town and cross-River West Brownsville share an important Railway bridge creating a balloon loop allowing the turning of complete coal trains. Newest is the limited access toll road PA Route 43, which connects the town to strategic points and southern Pittsburgh at Clairton. River hugging PA Route 88,[b] connects to towns up and down the Mon Valley and the historic National Road (now US Route 40) reached East Saint Louis, Illinois and connected the town to the immigrants arriving in the port of Baltimore traveling west on the Cumberland Turnpike and the National Road.

From its founding, well into the 19th century, as the first reachable population center west of the Alleghenies barrier range on the Mississippi watershed, the borough quickly grew into an industrial center, market town, transportation hub, outfitting center, and river boat-building powerhouse. It was a gateway destination for emigrants heading west to the Ohio Country when a trading post, and the new United States' Northwest Territory and their "legal successors" for travelers heading westwards on the various Emigrant Trails both to the Near West and later Far West from its founding until well into the 1850s. As outfitting center, the borough provided the markets for the small-scale industries in the surrounding counties—and also, quite a few in Maryland shipping goods over the pass by mule-train via the Cumberland Narrows toll-route.

Brownsville became a major center for building steamboats through the 19th century, producing 3,000 boats by 1888.

The borough developed in the late 19th century as a railroad yard and coking center, with other industries related to the rise of steel in the Pittsburgh area. It reached a peak of population of more than 8,000 in 1940. Postwar development occurred in suburbs, as was typical of the time. The restructuring of the railroad and steel industries caused a severe loss of jobs and population in Brownsville, beginning in the 1970s. The borough had a population of 2,331 as of the 2010 census.[3]

Contents

1 Infrastructure

1.1 Transportation

2 History

3 Geography

4 Demographics

5 Features

6 Education

6.1 Graduation rate

6.2 Votech

6.3 Charter schools

6.4 Intermediate unit

6.5 Public library

7 Notes

8 Notable people

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Infrastructure

Transportation

Brownsville is located on the banks of the Monongahela River, a major tributary of the Ohio River, one of North America's most important waterways. The Monongahela is fully navigable at Brownsville, and offers inexpensive barge transportation to Chicago, New Orleans, St. Marks in Florida, Minneapolis, Tulsa, Kansas City, Houston, and Brownsville, Texas, on the border with Mexico. The shipyards of Brownsville, Pennsylvania, provided Captain Richard King of Brownsville, Texas (founder of the King Ranch), with powerful new-built riverboats to navigate the fast currents of the Rio Grande in 1849.

Brownsville is connected to the satellite community of West Brownsville (in Washington County) by the Brownsville Bridge completed in 1914, which spans the Monongahela River. In 1960, the Lane Bane Bridge was constructed just downstream, and path of U.S. Route 40 was moved to the new high-level structure and new four lane highway by-passing old Route 40 until the two merged in the small bedroom neighborhood known locally as Malden[c]

History

In pre-Columbian times, the right bank Monongahela held several mounds where iron rich red stone predominated,[d] now believed to have been constructed by a branch of the Mound Builders cultures, but were believed by colonials to have been forts—leading to the area near the river crossing being called Redstone Old Fort in various colonial government records,[7] and later Fort Burd, when an arms cache was built there. By the time the region first became known to Dutch colonists and traders and the French in the 1640s, the lands were largely unoccupied,[e] but under the management of one tribe or shared by several groups of Iroquoian peoples, likely the Erie people, or Wenro people[f] and possibly shared with Seneca, the Shawnee people and the Susquehannocks. With all the rivers and streams tributary to the Monongahela, Youghiogheny, Allegheny Rivers, there is little known about the region's precise role in the Beaver Wars of the 17th century, but when French and Dutch and Swedish fur traders penetrated to the Greater Ohio Basin in the 1640s-1650s, the one thing that seemed clear to those observers was the lands later termed the Ohio Country seemed empty and unpopulated.

When in the 17th century, the occasional Englishman, as provincial Virginian or Marylanders generated their observations the emptiness of the region was confirmed. Before the 1750s, the area was 'colonized' by weakened remnant tribes such as the Delaware, the few Erie and the Susquehannock survivors (climbing the gaps of the Allegheny) the Iroquois allowed to move there as tributary peoples. These migrations occurred over the 70–80 years preliminary to the French and Indian War in the 1750s, where today's historians usually report the lands were long held as 'hunting territories'[g] of the powerful Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy.[h] During the Revolution, the Iroquois were divided whether to back the Colonies or the mother country, and mostly did neither, attempting to stay neutral. Nonetheless in 1778, agitated by British Officers lobbying for frontier attacks, mixed parties of Tories (Loyalists) and Iroquois committed atrocities in 1778, so Washington sent the Sullivan Expedition in 1779, which broke the power of the Iroquois—re-opened the Ohio Country to homesteader settlement. As a river crossing, the closest to the pass that reached the Monongahela, the town would see a lot of boots of settlers passing by.

View of Market Street historic district

Because colonial settlers believed that earthwork mounds were a prehistoric fortification, they called the settlement Redstone Old Fort; later in the 1760s–70s, it eventually became known as "Redstone Fort" or by the mid-1760s, "Fort Burd"— named after the officer who commanded the British fort constructed in 1759.[8] The fort was constructed during the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War) on the bluff above the river near a prehistoric earthwork mound that was also the site of historic Native American burial grounds.[9]

In 1774, a force from the Colony of Virginia garrisoned and occupied the stockade during Lord Dunmore's War against the Mingo and Shawnee peoples. It commanded the important strategic river ford of Nemacolin's Trail, the western path to the summit; this was later improved and called "Burd's Road". It was an alternative route down to the Monongahela River valley from Braddock's Road, which George Washington helped to build. Washington came to own vast portions of the lands on the west bank of the Monongahela; the Pennsylvania legislature named Washington County, after him and territorially, the largest county of the state.

Entrepreneur Thomas Brown acquired the western lands in what became Fayette County, Pennsylvania, around the end of the American Revolution.[10] He realized the opening of the pass through the Cumberland Narrows,[11] and war's end made the land at the western tip of Fayette County a natural springboard for settlers traveling to points west, such as Kentucky, Tennessee and Ohio. Many travelers used the Ohio River and its tributary, the Monongahela. Eventually the settlement became known as "Brownsville" after him. In the 1780s, Jacob Bowman bought the land on which he built Nemacolin Castle; he had a trading post and provided services and supplies to emigrant settlers.

Redstone Old Fort is mentioned in C. M. Ewing's The Causes of that so called Whiskey Insurrection of 1794 (1930) as the site of a July 27, 1791, meeting in "Opposition to the Whiskey Excise Tax," during the Whiskey Rebellion. It was the first meeting of that illegal frontier insurrection.[12]

Brownsville was positioned at the western end of the primitive road network (Braddock's Road to Burd's Road via the Cumberland Narrows pass) that eventually became chartered as the Cumberland toll road and later, after the Federal Government appropriated funds for its first ever road project, became known as the National Pike and well after tolls were removed, became the present-day U.S. Route 40, one of the original federal highways.

As an embarkation point for travelers to the west, Redstone/Brownsville, blessed by several nearby wide & deep water minor river tributaries could support building slips, soon became a center in the 19th century for the construction of riverine watercraft, initially keelboats and Flatboats, but later steamboats large and small. The entire region sprouted small industries utilizing local coal and Iron deposits feeding iron fittings and products to outfitting settlers about to embark on the river. After 1845, its boats were used even by those intending to later take the Santa Fe Trail or Oregon Trail, as floating on a poleboat by river to St. Louis or other ports on the Mississippi River was generally safer, easier and far faster than overland travel of the time.[i]

A large flatboat building industry developed at Brownsville exploiting the flats across the river in present-day West Brownsville to erect building slips. This was followed by its rapid entry into the building of steamboats: local craftsmen built the Enterprise in 1814, the first steamboat powerful enough to travel down the Mississippi River to New Orleans and back.[14] Earlier boats did not have enough power to go upstream against the river's current. Brownsville developed as an early center of the steamboat-building industry in the 19th century. The Monongahela converges with the Ohio River at Pittsburgh and allowed for quick traveling to the western frontier.[15] From 1811 to 1888, boatyards produced more than 3,000 steamboats.[14] Steamboats were gradually supplanted in the passenger carrying trade after the American Civil War as the construction of railroad networks surged, but concurrently grew important locally on the Ohio River and tributaries as tugs delivering barge loads of minerals to the burgeoning steel industries growing up along the watershed from the 1850s. Steamboat propulsion would not be replaced by diesel powered commercial tugs until the technology matured in the mid-20th century.

Plaque commemorating the first cast iron bridge built in the United States

The first all-cast iron arch bridge constructed in the United States was built in Brownsville to carry the National Pike (at the time a wagon road) across Dunlap's Creek. See Dunlap's Creek Bridge. The bridge is still in use in 2019.

After the 1853 completion of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad to the Ohio, outfitting emigrant wagon trains in Brownsville declined in importance.

Yet the rise of the steel industry in the Pittsburgh area led Brownsville to develop as a railroad yard and coking center, generally integrated into other towns within the valley, so Brownsville and West Brownsville were tied to regional operations and while no one yard had space enough to be large, each township along the river shared resources and functioned as an elongated yard system. With its new role as Railroad center and coking center together with the decline of outfitting, the town gradually lost its diverse mix of businesses, but nonetheless, generally prospered during the early 20th century through the 1960s. Brownsville tightened its belt during the Great Depression, but the local economy resumed growth with the increased demand for steel during and after World War II, when many infrastructure projects hatched the improved and rerouted U.S. Route 40 over the new high level bridge, clearing up a perennial traffic congestion problem.

In 1940, 8,015 people lived in Brownsville. Its postwar growth led to the development of cross-county-line suburbs such as Malden, Lowhill, and Denbeau Heights (Denbow Heights), which were mainly bedroom communities within commuting distance. In the mid-1970s after the OPEC Oil Embargo of 1973–74 triggered a recession, with the restructuring of the steel industry and loss of industrial jobs, Brownsville suffered a severe decline, along with much of the Rust Belt. Generally, the region has declined in population and vitality ever since.

By 2000, the population was 2,804, as younger people had moved away to areas with more jobs. In 2011, Brownsville has a handful of buildings that are condemned or boarded up. Abandoned buildings include the Union Station of the railroad, several banks, and other businesses. The sidewalks around the town are still intact and usable.

Brownsville attracted major entertainers in the early postwar years, who also were performing in nearby Pittsburgh. According to Mike Evans in his book Ray Charles: The Birth of Soul (2007), the singer developed his hit "What'd I Say" as part of an after-show jam in Brownsville in December 1958.[16]

Lester Ward was elected mayor in 2009.

Geography

Brownsville is located at 40°1′12″N 79°53′22″W / 40.02000°N 79.88944°W / 40.02000; -79.88944 (40.020026, -79.889536),[17] situated on the east (convex) side of a broad sweeping westward bend in the northerly flowing Monongahela River on the northwestern edge of Fayette County. The river's action eroded the steep-sided sandstone hills, creating shelf-like benches and connecting sloped terrain that gave the borough lowland areas adjacent to or otherwise accessible to the river shores. Much of the borough's residential buildings are built above the elevation of the business district.

The opposite river shore of Washington County is, uncharacteristically for the region, shaped even lower to the water surface and is generally flatter. A small hamlet called West Brownsville developed on the western shore, with a current population of 992. Historically the area was a natural river crossing, and it was the site of development of a ferry, boat building and a bridge to carry roads. When the nascent United States government appropriated funds for its first road building project, in 1811 Brownsville was chosen as an early intermediate target destination along the new National Road. Until a bridge was built across the river, Brownsville was the western terminus.

Redstone Creek is a local tributary stream of the Monongahela River, entering just north of Brownsville. Its color came from the ferrous sandstone that lined its bed, as well as the sandstone heights near the Old Forts. The creek was wide enough for settlers to build, dock and outfit numerous flatboats, keelboats, and other river craft. Its builders made thousands of pole boats that moved the emigrants who settled the vast Northwest Territory. Later Brownsville industry built the first steamboats on the inland rivers, and many hundreds afterwards.[citation needed]

Colonists used the term "Old Forts" for the mounds and earthworks created by the prehistoric Mound Builders cultures. Archeologists and anthropologists have since determined that many prehistoric Native American cultures in North America along the Mississippi River and its tributaries built massive earthworks for ceremonial, burial and religious purposes over a period of thousands of years prior to European encounter. For instance, the Mississippian culture, reaching a peak about 1150 CE at Cahokia in present-day Illinois, had sites throughout the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys, and into the Southeast. Archaeological research is ongoing working to tie the local mounds and others regionally close to a particular era and culture.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 698 | — | |

| 1820 | 976 | 39.8% | |

| 1830 | 1,222 | 25.2% | |

| 1840 | 1,362 | 11.5% | |

| 1850 | 2,369 | 73.9% | |

| 1860 | 1,934 | −18.4% | |

| 1870 | 1,749 | −9.6% | |

| 1880 | 1,489 | −14.9% | |

| 1890 | 1,417 | −4.8% | |

| 1900 | 1,552 | 9.5% | |

| 1910 | 2,324 | 49.7% | |

| 1920 | 2,502 | 7.7% | |

| 1930 | 2,869 | 14.7% | |

| 1940 | 8,015 | 179.4% | |

| 1950 | 7,643 | −4.6% | |

| 1960 | 6,055 | −20.8% | |

| 1970 | 4,856 | −19.8% | |

| 1980 | 4,043 | −16.7% | |

| 1990 | 3,164 | −21.7% | |

| 2000 | 2,804 | −11.4% | |

| 2010 | 2,331 | −16.9% | |

| Est. 2016 | 2,270 | [2] | −2.6% |

| Sources:[18][19][20] | |||

As of the census[19] of 2000, there were 2,804 people, 1,238 households, and 716 families residing in the borough. The population density was 2,796.6 people per square mile (1,082.6/km²). There were 1,550 housing units at an average density of 1,545.9 per square mile (598.5/km²). The racial makeup of the borough was 85.95% White, 11.41% African American, 0.11% Native American, 0.07% Asian, 0.21% from other races, and 2.25% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.82% of the population.

There were 1,238 households, out of which 24.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.2% were married couples living together, 17.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.1% were non-families. 38.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 20.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.24 and the average family size was 2.97.

In the borough the population was spread out, with 23.2% under the age of 18, 9.0% from 18 to 24, 25.6% from 25 to 44, 21.1% from 45 to 64, and 21.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.7 males.

The median income for a household in the borough was $18,559, and the median income for a family was $32,662. Males had a median income of $31,591 versus $21,830 for females. The per capita income for the borough was $13,404. About 28.8% of families and 34.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 51.2% of those under age 18 and 17.9% of those age 65 or over.

Features

Dunlap's Creek Bridge (1839) under part of the level stretch of Market Street, carrying old U.S. Route 40 over Dunlap's Creek in Brownsville, is the nation's oldest cast iron bridge in existence. (Capt. Richard Delafield, engineer; John Snowden and John Herbertson, foundrymen)

The Flatiron Building (c. 1830), constructed as a business building in thriving 19th-century Brownsville, is one of the oldest, most intact iron commercial structures west of the Allegheny Mountains. Over its history, it has housed private commercial entities as well as public, such as a post office. It is the unofficial "prototype" for the flatiron buildings seen across the United States. The most notable is the Flatiron Building in Market Square in New York City.

After nearly being demolished, the building was saved by the Brownsville Area Revitalization Corporation (BARC). Throughout two decades, via private and public grants, BARC has restored the Flatiron Building as an historic asset to Brownsville. The Flatiron Building Heritage Center, located within the building at 69 Market Street, holds artifacts from Brownsville's heyday, as well as displays about the community's important coal and coke heritage. The Frank L. Melega Art Museum, located with the Heritage Center, displays many examples of this local southwestern Pennsylvanian's famous artwork, depicting the coal and coke era in the surrounding tri-state region.[21]

In addition to the Dunlap's Creek Bridge, Brownsville is the location of other properties on the National Register of Historic Places. They are Bowman's Castle (Nemacolin Castle), Brownsville Bridge, St. Peter's Church, and Thomas H. Thompson House. There are two national historic districts: the Brownsville Commercial Historic District and Brownsville Northside Historic District.[22]

Education

Map of Fayette County, Pennsylvania public school districts showing a portion of Brownsville Area SD in orange

Map of Washington County, Pennsylvania public school districts showing the portion of Brownsville Area SD

The Brownsville Area School District serves Brownsville as well as several nearby communities. Enrollment declined to 1,660 pupils in 2015.[23] The district served 1,883 pupils in 2006.[24] The district operates four schools::

Brownsville Area High School (9–12)- Brownsville Area Middle School (6–8)

- Brownsville Area Elementary School (K-5)

Brownsville Area School District was ranked 468th out of 493 Pennsylvania school districts in 2015, by the Pittsburgh Business Times.[25] The ranking is based on the last 3 years of student academic achievement as demonstrated by PSSAs results in: reading, writing, math and science PSSAs and the three Keystone Exams: (literature, Algebra 1, Biology I) given in high school.[26] Three school districts were excluded because they do not operate high schools (Saint Clair Area School District, Midland Borough School District, Duquesne City School District). The PSSAs are given to all children in grades 3rd through 8th. Adapted PSSA examinations are given to children in the special education programs. Writing exams were given to children in 5th and 8th grades.[27] In 2007, the district ranked 473rd out of 501 school districts.[28]

- Opportunity - Lowest achievement - Scholarship list

In April 2014, the Pennsylvania Department of Education released a report identifying that three Brownsville Area School District schools were among the lowest achieving schools for reading and mathematics in the state.[29] Central Elementary School, Brownsville Area Middle School and Brownsville Area High School were all on the list. The high school has been on the list each year since 2011–12. The Middle School and Central Elementary School were both on and off the list over the past 5 years. Parents and students may be eligible for scholarships to transfer to another public or nonpublic school through the state's Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit Program passed in June 2012.[30] The scholarships are limited to those students whose family's income is less than $60,000 annually, with another $12,000 allowed per dependent. Maximum scholarship award is $8,500, with special education students receiving up to $15,000 for a year's tuition. Parents pay any difference between the scholarship amount and the receiving school's tuition rate. Students may seek admission to neighboring public school districts. Each year the PDE publishes the tuition rate for each individual public school district.[31] Fifty-three public schools in Allegheny County are among the lowest-achieving schools in 2011. According to the report, parents in 414 public schools (74 school districts) were offered access to these scholarships. Funding for the scholarships comes from donations by businesses which receive a state business tax credit for donating.

AYP status In 2012, Brownsville Area School District declined to District Improvement level I Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) status due to chronic, low academic achievement.[32] Brownsville Area HIgh School declined further to Corrective Action II 1st Year AYP status,[33] due to low student achievement. The administration was required by the federal government under the No Child Left Behind Act to notify parents of the school's poor performance and to offer transferring to a quality school in the district. No other high school is operated in the district.

- 2015 School Performance Profile

Brownsville Area High School achieved 52.9 out of 100. Reflects on grade level reading, mathematics and science achievement. The PDE reported that just 60% of the high school's students were on grade level in reading/literature. In Algebra 1, 47.37% of students showed on grade level skills at the end of the course. In Biology I, 42.48% demonstrated on grade level science understanding at the end of the course.[34] Statewide, 53 percent of schools with an eleventh grade achieved an academic score of 70 or better. Five percent of the 2,033 schools with 11th grade were scored at 90 and above; 20 percent were scored between 80 and 89; 28 percent between 70 and 79; 25 percent between 60 and 69 and 22 percent below 60. The Keystone Exam results showed: 73 percent of students statewide scored at grade-level in English, 64 percent in Algebra I and 59 percent in biology.[35][36]

Graduation rate

In 2015, Brownsville Area School District's graduation rate was 77.42%.[37]

- 2014 – 83.73%[38]

- 2013 – 78.40%[39]

- 2012 – 86.78%[40]

- 2011 – 77%.[41]

- 2010 – 86.78%, the Pennsylvania Department of Education issued a new, 4-year cohort graduation rate.[42]

Votech

High school aged students can attend the taxpayer funded Fayette County Career and Technical Institute, located in Uniontown, for training in: the building trades, auto mechanics, culinary arts, allied health careers and other areas. The School also offers driver's education courses and dual enrollment college courses in cooperation with Westmoreland County Community College. The Fayette County Career & Technical Institute is accredited by the Commission on Secondary Schools of the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools. Fayette County Career and Technology Institute is funded by a consortium of the school districts, which includes: Uniontown Area School District, Albert Gallatin Area School District, Brownsville Area School District and Laurel Highlands School District. The school districts pay a per pupil fee to the tech school each year based on the number of their students attending the tech school.

Charter schools

Brownsville borough residents may also apply to attend any of the Commonwealth's 13 public cyber charter schools (in 2015) at no additional cost to the parents. This includes SusQ Cyber Charter School which is locally operated. The resident's public school district is required to pay the charter school and cyber charter school tuition for residents who attend these public schools.[43][44] The tuition rates for Brownsville Area School District for Elementary School was $7,465.49 and for high school was $8,427.07 in 2014.[45] By Commonwealth law, if the district provides transportation for its own students, then the district must provide transportation to any school that lies within 10 miles of its borders. Residents may also seek admission for their school-aged child to any other public school district. When accepted for admission, the student's parents are responsible for paying an annual tuition fee set by the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

Intermediate unit

Intermediate Unit #1 provides a wide variety of services to children living in its region which includes Brownsville.[46] Early screening, special education services, speech and hearing therapy, autistic support, preschool classes and many other services are available. Services for children during the preschool years are provided without cost to their families when the child is determined to meet eligibility requirements. Intermediate units receive taxpayer funding: through subsidies paid by member school districts; through direct charges to users for some services; through the successful application for state and federal competitive grants and through private grants.[47]

Public library

Community members have access to the Brownsville Free Public Library which is headquartered at 100 Seneca Street, Brownsville.[48] Through it all Pennsylvania residents have access to all POWER Library[49] online resources, as well as Ask Here PA a research assistance service.

Notes

^ In Somerset County near Fort Necessity traffic up through the Cumberland Narrows pass could take a northwards jog and descend along the Youghiogheny River from near Ohiopyle or descend by a more direct route through the area that later became Fayette County seat, Uniontown and descend near the Mound Builders culture's artifacts named as Redstone Old Fort along Nemacolin's Trail.

^ Via West Brownsville and the Brownsville Bridge.

^ Malden is a hamlet of four groups of a few dozen homes each plus those lining Old U.S. Route 40, the National Road, with the two largest suburban-style housing developments ranged off to either side of the old 40-highway after it has climbed out of the valley of the Monongahela and reached a mostly flat stretch from east to west.[4] In the heyday of Conestoga wagon migration travels and with the congestion of Brownsville's hilly terrain, the flat lands about Malden just two-to-three further on offered rare open spaces for west-bound travelers to camp and recuperate from the rigorous mountain descent.

Before the highway construction of the late 1950s was completed in the early 60s, two additional branchlike housing concentrations existed, the lined either side of 'California Road' which intersected Old U.S. 40 in the heart of the small business district at landmarks, Paci's Restaurant and Cuppies Drive-In Theatre;[5][6] the former set in a 17th century stone Inn. The fourth concentration of housing extended from beside and beyond Cuppies Drive-In for over a mile either side of U.S. 40, now once again, single lane secondary highway. The community has few stores and several housing developments sited along a hilly plateau above the river valleys. The California Area High School is in part sited within parts of Malden.

^ Due to the sparse availability of building space in Brownsville during its boom days 1800–1870, these mound builders constructs were demolished and only a little of them were available for examination by modern archaeologists.

^ The Dutch & Swedish fur traders did not leave historical documents, so accounts are decidedly second and third hand reports, but the rich lands of West Virginia, Western Pennsylvania, and Ohio—later called the Ohio Country were all reported as lacking population and Iroquois or Iroquoian hunting lands. Three Iroquoian military super-powers each had access to the region before the 1670s: The Erie peoples, the Susquehannock peoples, and the Confederacy of the Iroquois, whereafter the Iroquois emerged decimated, but atop the heap of survivors of the Beaver Wars as the Kingdom of England's colonies took over control of most of the Eastern seaboard after the 1660s. Settlements even through the lower Susquehanna River valley and Western Maryland were inhibited by the Iroquois well into the 1750s and those of the Province of Virginia, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania west of the Alleghenies were 'extremely chancy' until after the American Revolution. After the formation of the United States, the settlement by the government of conflicting colonial land claims and the establishment of Western Pennsylvania's and Virginia's western borders and the Northwest Territory on July 13, 1787 then served to spur western settlement from a trickle into a flood of emigrants.

^ French Jesuit missionaries and traders were required to report annually on events in the new world, so that their Chronicles' opine Western Pennsylvania and Eastern Ohio essentially vacant, and the Wenro small in numbers, it leads to speculation the Wenro recently lost a big internecine war, and had been driven into the few towns between present-day Buffalo and Rochester, NY. The Wenro tribes were sandwiched between the Iroquois' Seneca people's lands, and those of the Erie people—both thought to be militarily powerful in the mid-17th century.

^ as 'hunting territories' of the powerful Iroquois, likely held as conquest prizes for kicking off then prevailing the many decades of the Beaver Wars, when tribe after tribe fell to other Native Americans in vicious territorial wars historians tell us, were like nothing the Indians normally practiced.

^ The Erie had preemptively attacked the Iroquois c. 1653, but lost by 1657, at which time Iroquois were known to claim lands as far south as the right bank of the Ohio opposite Western Kentucky shorelines. In the early 1950s, the closest Indian towns were Mingo communities both along the Youghiogheny to the Northeast and near Mingo Creek above present-day Donora, Pennsylvania. Shawnee and Seneca were also living in the wider area, the former a French ally, and the latter as Iroquois, the blood enemies of the French along with their Mingo relatives. Susquehannocks suffered a devastating succession of plagues c. 1671, leaving the Iroquois take them over as well as the Delaware groups tributary to the once mighty Susquehannocks.

^ According to the book The Delaware and Lehigh Canals[13] the Philadelphia to Pittsburgh used to take just about a month by wagon or half-that on horseback. With the construction of the Pennsylvania Canal System and the Allegheny Portage Railroad, a traveler willing to stay on and sleep aboard the mule towed barges could make the same trip in just four days after the early 1830s.

Notable people

John Brashear (1840–1920), astronomer and builder of scientific instruments

Thomas Brown (1738–1797), founder and entrepreneur

Vincent Colaiuta (born 1956 in Brownsville, but lived in Republic), renowned jazz-rock-pop drummer

Richard Gary Colbert (February 12, 1915 – December 2, 1973), four-star admiral in the United States Navy and former President of the Naval War College

Doug Dascenzo (born 1964), former MLB outfielder with the Chicago Cubs, Texas Rangers and San Diego Padres

Bill Eadie (born 1947), three-time WWF tag team champion Ax of Demolition

Daniel French (1770–1853), pioneering designer and builder of steam engines

Israel Gregg (1775–1847), first captain of the steamboat Enterprise

Alfred Hunt (1817–1888), first president of Bethlehem Iron Company, precursor of Bethlehem Steel Corporation[50][51]

Esther Hunt (1751–1820), a pioneer who lived on America's frontier as a wife, a mother and a leader in her Quaker faith[52][53]

Lisa Kirk (1925–1990), singer and actress

Philander C. Knox (1853–1921), lawyer and politician who served as United States Attorney General (1901–1904), a senator from Pennsylvania (1904–1909, 1917–1921) and Secretary of State (1909–1913)

Gary L. Lancaster (1949–2013), United States court judge

Andy Linden (1922–1987), Indy car driver

George Marcus (born 1946), anthropologist

Thomas Novak (born 1952), mining safety engineer

Samuel Shapiro, state treasurer of Maine (1981–1996)

Henry Miller Shreve (1785–1851), pioneering steamboat captain, and steamboat designer

Jacob B. Sweitzer (1821–1881), Civil War Union Army brigade commander

Joe Taffoni (born 1945), NFL player

Amos Townsend (1821–1895), U.S. congressman

Bill Viola (born 1947), mixed martial arts pioneer

Andy Gresh (born 1974) talk show host, television host, color commentator

References

^ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Aug 13, 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ ab "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

^ ab "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Brownsville borough, Pennsylvania". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

^ Malden mailing addresses use RD#2 Brownsville as postal addresses, but the lands and school systems are administered as part of Washington, County. It lies nearly equidistant from Centerville, Brownsville, and California.

^ Landmark Cuppies Drive-In, later renamed the Malden Drive-in under new management operated for about 60 years before 2007, and was a well-known landmark in four counties of Southwestern Pennsylvania.

^ www.cinematreasures.org/theaters/10344

^ See notes quoted in Redstone Old Fort.

^ Site designed by Meghan Hoke on April 21, 2001. The French and Indian War in Southwestern Pennsylvania. "Fort Burd in the French and Indian War in Southwestern Pennsylvania". Retrieved 2009-07-02.In 1759, the Pennsylvania Militia constructed Fort Burd south of Pittsburgh high atop a hill overlooking the Monongahela River. The fort was used as a supply depot for the British Army during the French and Indian War and made river transportation to Pittsburgh possible at that time. A sturdy square fort, its curtain walls were 97.5 feet and its bastions had thirty-foot faces with sixteen-foot flanks. This stockade was surrounded by a ditch. Fort Burd was constructed on the same site as an even earlier Indian fortification known as Redstone Old Fort.

^ "Nemacolin (Bowman's) Castle". Brownsville Historical Society. 2009-07-02.The site itself is steeped in history, once the location of Indian burial grounds and fortifications, the area was the intended destination of Chief Nemacolin when he guided the Cresap expeditions across the mountains, establishing the Nemacolin Trail which later became the approximate route of the National Road. In 1759, during the French and Indian Wars, Fort Burd was constructed very near the Castle's current site. In 1780, Jacob Bowman purchased a building lot from Thomas Brown, co founder of Brownsville for 23 English pounds. He named the site in honor of Chief Nemacolin, setting up a trading post and later building the Castle around it.

Missing or empty|url=(help)

^ Official borough website. "Welcome to Brownsville". Retrieved 2009-07-02.Brownsville situated, at the western most point of Fayette County, on the National Road and overlooking the Monongahela River was the gateway to the west. Thomas Brown, realizing that pioneers would be drawn to the Brownsville area to get to the Ohio Valley and the U.S. state of Kentucky, purchased land in the 18th century and by mid-18th century a settlement was being mapped out. It was then, that the community of Brownsville (named for Thomas Brown and formerly known as Redstone Old Fort) became a "keel-boat" building center as well as other businesses for travelers. The businessmen from Brownsville supplied transportation and supplies to the traveling pioneers, and the settlement became very prosperous. The steamboat industry soon took over to facilitate traffic along the Monongahela River. The very first steamboat, the 'Enterprise,' to travel to New Orleans and return by its own power was designed and built in the Brownsville boatyards and launched from the Brownsville Wharf in 1814.

^ See Nemacolin's Path, the French and Indian War (causes) and the history of George Washington as lieutenant and major in the Colonial Virginia Militia.

^ "Timeline", Whiskey Rebellion

^ Bartholomew, Ann M.; Metz, Lance E.; Kneis, Michael (1989). DELAWARE and LEHIGH CANALS, 158 pages (First ed.). Oak Printing Company, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: Center for Canal History and Technology, Hugh Moore Historical Park and Museum, Inc., Easton, Pennsylvania. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0930973097. LCCN 89-25150.

^ ab Mary Pickels, "Oral history project focuses on Mon Valley's steamboat era", Pittsburgh TRIBUNE-REVIEW, 26 July 2010, accessed 8 February 2012

^ Marc N. Henshaw, The Steamboat Industry in Brownsville Pennsylvania: An Ethnohistoric Perspective on the Economic Change in the Monongahela River Valley, Ypsilanti, Michigan: Western Michigan University, 2004

^ Mike Evans, Ray Charles: The Birth of Soul, London: Omnibus Press, 2007

^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

^ "Census of Population and Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

^ ab "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

^ "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

^ "BARC Flatiron Building", Flatiron Center

^ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (December 4, 2015). "Brownsville Area School District Fast Facts 2015".

^ PDE, Enrollment and Projections by LEA and School 2006–2020, 2010

^ Pittsburgh Business Times (April 10, 2015). "Guide to Pennsylvania Schools Statewide School District Ranking 2015".

^ Pittsburgh Business Times (April 11, 2014). "What makes up a district's School Performance Profile score?".

^ Paul Jablow (November 18, 2015). "Understanding the PSSA exams". The Notebook.

^ "Three of top school districts in state hail from Allegheny County". Pittsburgh Business Times. May 23, 2007. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education, Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit Program 2014–15, April, 2014

^ Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development (April 2014). "Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit Program FAQ".

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (May 2012). "Tuition rate Fiscal Year 2011-2012".

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (September 21, 2012). "Brownsville Area School District AYP Overview 2012".

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (September 21, 2012). "BROWNSVILLE AREA High School AYP Overview 2012".

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (November 4, 2015). "Brownsville Area High School School Performance Profile 2015".

^ Jan Murphy (November 4, 2015). "Report card for state's high schools show overall decline". Pennlive.com.

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (November 4, 2015). "2015 Keystone Exam School Level Data".

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (December 4, 2015). "Brownsville Area School District Performance profile 2015".

^ PDE, Graduation rate by LEA, 2014

^ PDE, Graduation rate by LEA, 2013

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (September 21, 2012). "Brownsville Area School District AYP Data Table 2012".

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (September 29, 2011). "Brownsville Area School District AYP Data Table".

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (March 15, 2011). "New 4-year Cohort Graduation Rate Calculation Now Being Implemented". Archived from the original on September 14, 2010.

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (2013). "Charter Schools".

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (2013). "What is a Charter School?".

^ Pennsylvania Department of Education (May 2013). "Pennsylvania Public School District Tuition Rates".

^ http://www.iu1.k12.pa.us/

^ Intermediate Unit 1 Administration, About the Intermediate Unit 1, 2015

^ http://www.bfpl.org/index.html

^ http://www.powerlibrary.org/

^ Alfred Hunt's obituary "The announcement of the death of Alfred Hunt, president of the Bethlehem Iron Company, will be a shock to his numerous friends throughout the Lehigh Valley and the State. The sad event occurred last evening at the home of his brother, Mordecai Hunt, in Moorestown, N. J." "Mr. Hunt was born of Quaker parentage, at Brownsville, Pa., on April 5, 1817, and was consequently in the 71st year of his age."

^ Hunt family history

^ Specht, Neva Jean (1997), Mixed blessing: trans-Appalachian settlement and the Society of Friends, 1780–1813, Ph. D. dissertation, University of Delaware

^ Specht, Neva Jean (2003), "Women of one or many bonnets?: Quaker women and the role of religion in trans-Appalachian settlement", NWSA Journal 15 (2): 27–44

Further reading

- Brownsville Historical Society (1883). The three towns: a sketch of Brownsville, Bridgeport, and West Brownsville. Brownsville, Pennsylvania: Tru Copy Printing. (1976, second edition; 1993, third edition)

- Ellis, Franklin (1882). History of Fayette County, Pennsylvania, with biographical sketches of many of its pioneers and prominent men. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts and Company.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brownsville, Pennsylvania. |

- Brownsville borough official website

- Brownsville Area Revitalization Corporation

One Year in Brownsville - WQED special