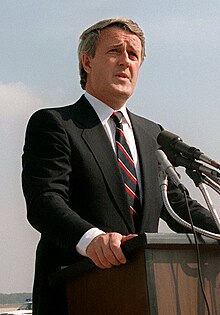

Brian Mulroney

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP The Right Honourable Brian Mulroney PC CC GOQ | |

|---|---|

| |

| 18th Prime Minister of Canada | |

In office September 17, 1984 – June 25, 1993 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governor General | Jeanne Sauvé Ray Hnatyshyn |

| Deputy | Erik Nielsen (1984–86) Don Mazankowski (1986–93) |

| Preceded by | John Turner |

| Succeeded by | Kim Campbell |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

In office August 29, 1983 – September 17, 1984 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Erik Nielsen |

| Succeeded by | John Turner |

| Leader of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada | |

In office June 11, 1983 – June 13, 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Erik Nielsen (interim) |

| Succeeded by | Kim Campbell |

| Member of the Canadian Parliament for Charlevoix | |

In office November 21, 1988 – September 8, 1993[1] | |

| Preceded by | Charles Hamelin |

| Succeeded by | Gérard Asselin |

| Member of the Canadian Parliament for Manicouagan | |

In office September 4, 1984 – November 21, 1988 | |

| Preceded by | André Maltais |

| Succeeded by | Charles Langlois |

| Member of the Canadian Parliament for Central Nova | |

In office August 29, 1983 – September 4, 1984 | |

| Preceded by | Elmer M. MacKay |

| Succeeded by | Elmer M. MacKay |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Martin Brian Mulroney (1939-03-20) March 20, 1939 Baie-Comeau, Quebec, Canada |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Political party | Progressive Conservative (until 2003) |

| Other political affiliations | Conservative (2003–present) |

| Spouse(s) | Mila Pivnički (m. 1973) |

| Children | 4, including Caroline and Ben |

| Residence | Westmount, Quebec, Canada Palm Beach, Florida, U.S. |

| Education | Political Science (B.A., 1959) Law (B.C.L. & LL.D., 1964) |

| Alma mater | St. Francis Xavier University Université Laval |

| Profession | Lawyer, businessman |

| Signature | |

Martin Brian Mulroney PC CC GOQ (born March 20, 1939) is a Canadian politician who served as the 18th Prime Minister of Canada from September 17, 1984, to June 25, 1993. His tenure as prime minister was marked by the introduction of major economic reforms, such as the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement and the Goods and Services Tax, and the rejection of constitutional reforms such as the Meech Lake Accord and the Charlottetown Accord. Prior to his political career, he was a prominent lawyer and businessman in Montreal.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Family

3 Education

4 Builds reputation, gains publicity

5 Loses first leadership race, 1975–76

6 Business leadership

7 Party leader

8 Prime minister (1984–1993)

8.1 First mandate (1984–1988)

8.1.1 Foreign policy

8.1.2 Free trade

8.2 Second mandate (1988–1993)

8.3 Retirement

8.4 Airbus/Schreiber affair

9 After politics

9.1 Current political affiliation

9.2 Legacy

10 Memoir

11 Honours

11.1 Honorary degrees

11.2 Order of Canada Citation

12 Supreme Court appointments

13 Notable cabinet ministers

14 Arms

15 See also

16 References

17 Further reading

17.1 Scholarly studies

17.2 Popular books

18 External links

Early life

Mulroney was born on March 20, 1939, in Baie-Comeau, Quebec, a remote and isolated town in the eastern part of the province. He is the son of Irish Canadian Catholic parents, Mary Irene (née O'Shea) and Benedict Martin Mulroney,[2] who was a paper mill electrician. As there was no English-language Catholic high school in Baie-Comeau, Mulroney completed his high school education at a Roman Catholic boarding school in Chatham, New Brunswick operated by St. Thomas University (in 2001, St. Thomas University named its newest academic building in his honour). Benedict Mulroney worked overtime and ran a repair business to earn extra money for his children's education, and he encouraged his oldest son to attend university.[3]

Mulroney would frequently tell stories about newspaper publisher Robert R. McCormick, whose company had founded Baie-Comeau. Mulroney would sing Irish songs for McCormick,[4] and the publisher would slip him $50.[5] He grew up speaking English and French fluently.[6]

Family

On May 26, 1973, he married Mila Pivnički, the daughter of a Serbian doctor, Dimitrije Mita Pivnički, from Sarajevo.[7] The Mulroneys have four children: Caroline, Benedict (Ben), Mark and Nicolas. His only daughter Caroline unsuccessfully ran for the 2018 Ontario PC leadership race and represents the party in York-Simcoe.[8]. Caroline is currently the Attorney General of Ontario.

Ben is the host of CTV morning show Your Morning, while Mark and Nicolas both work in financial industry in Toronto.[9]

Mulroney is the grandfather of Lewis H. Lapham III, and twins Pierce Lapham and Elizabeth Theodora Lapham, and Miranda Brooke Lapham from daughter, Caroline; and twins Brian Gerald Alexander and John Benedict Dimitri and daughter Isabel Veronica (known as Ivy) by son Ben and his wife Jessica. The twins served as page boys and train bearers at the wedding of Meghan Markle with Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex on 19 May 2018, which their parents also attended, and their sister was one of the bridesmaids.

Education

Mulroney entered St. Francis Xavier University in the fall of 1955 as a 16-year-old freshman. His political life began when he was recruited to the campus Progressive Conservative group by Lowell Murray and others, early in his first year. Murray would become a close friend, mentor, and adviser who was appointed to the Senate of Canada in 1979. Other important, lasting friendships made there by Mulroney included Gerald Doucet, Fred Doucet, Sam Wakim, and Patrick MacAdam. Mulroney enthusiastically embraced political organization, and assisted the local PC candidate in his successful 1956 Nova Scotia provincial election campaign; the PCs, led provincially by Robert Stanfield, swept to a surprise victory.[3]

Mulroney became a youth delegate and attended the 1956 leadership convention in Ottawa. While initially undecided, Mulroney was captivated by John Diefenbaker's powerful oratory and easy approachability. Mulroney joined the "Youth for Diefenbaker" committee which was led by Ted Rogers, a future scion of Canadian business. Mulroney struck an early friendship with Diefenbaker (who won the leadership) and received telephone calls from him.[6]

Mulroney won several public speaking contests at St. Francis Xavier University, was a star member of the school's debating team, and never lost an interuniversity debate. He was also very active in campus politics, serving with distinction in several Model Parliaments, and was campus prime minister in a Maritimes-wide Model Parliament in 1958.[3]

Mulroney also assisted with the 1958 national election campaign at the local level in Nova Scotia; a campaign that led to the then-largest majority in Canadian history.[10] After graduating from St. Francis Xavier with a degree in political science in 1959, Mulroney at first pursued a law degree from Dalhousie Law School in Halifax. It was around this time that Mulroney also cultivated friendships with the Tory premier of Nova Scotia, Robert Stanfield, and his chief adviser Dalton Camp. In his role as an 'advance man', Mulroney significantly assisted with Stanfield's successful 1960 re-election campaign. Mulroney neglected his studies, then fell seriously ill during the winter term, was hospitalized, and, despite getting extensions for several courses because of his illness, left his program at Dalhousie after the first year.[3] He then applied to Université Laval in Quebec City, and restarted first-year law there the next year.

In Quebec City, Mulroney befriended future Quebec Premier Daniel Johnson, Sr, and frequented the provincial legislature, making connections with politicians, aides, and journalists. At Laval, Mulroney built a network of friends, including Lucien Bouchard, Bernard Roy, Michel Cogger, Michael Meighen, and Jean Bazin, that would play a prominent role in Canadian politics for years to come.[11] During this time, Mulroney was still involved in the Conservative youth wing and was acquainted with the President of the Student Federation, Joe Clark.[citation needed]

Mulroney secured a plum temporary appointment in Ottawa during the summer of 1962, as the executive assistant to Alvin Hamilton, minister of agriculture. Then a federal election was called, and Prime Minister Diefenbaker appointed Hamilton as the acting prime minister for the rest of the campaign. Hamilton took Mulroney with him on the campaign trail, where the young organizer gained valuable experience.[12]

Builds reputation, gains publicity

After graduating from Laval in 1964, Mulroney joined the Montreal law firm now known as Norton Rose Fulbright, which at the time was the largest law firm in the Commonwealth of Nations. Mulroney twice failed his bar exams, but the firm kept him due to his charming personality.[3] After ultimately passing his bar exams, Mulroney was admitted to the Quebec bar in 1965, and became a labour lawyer, which was then a new and exciting field of law in Quebec. Mulroney's superb political skills of conciliation and negotiation, with opponents often polarized and at odds, proved ideal for this field. He was noted for ending several strikes along the Montreal waterfront where he met fellow lawyer W. David Angus of Stikeman Elliott, who would later become a valuable fundraiser for his campaigns.[citation needed] In addition, he met fellow then Stikeman Elliott lawyer Stanley Hartt, who later played a vital role assisting him during his political career as Mulroney Chief of Staff.[13]

In 1966, Dalton Camp, who by then was president of the Progressive Conservative Party, ran for re-election in what many believed to be a referendum on Diefenbaker's leadership. Diefenbaker had reached his 70th birthday in 1965. Mulroney joined with most of his generation in supporting Camp and opposing Diefenbaker, but due to his past friendship with Diefenbaker, he attempted to stay out of the spotlight. With Camp's narrow victory, Diefenbaker called for a 1967 leadership convention in Toronto. Mulroney joined with Joe Clark and others in supporting former Justice minister E. Davie Fulton. Once Fulton dropped off the ballot, Mulroney helped in swinging most of his organization over to Robert Stanfield, who won. Mulroney, then 28, would soon become a chief adviser to the new leader in Quebec.[citation needed]

Mulroney's professional reputation was further enhanced when he ended a strike that was considered impossible to resolve at the Montreal newspaper La Presse. In doing so, Mulroney and the paper's owner, Canadian business mogul Paul Desmarais, became friends. After his initial difficulties, Mulroney's reputation in his firm steadily increased, and he was made a partner in 1971.[3]

Mulroney's big break came during the Cliche Commission in 1974,[14] which was set up by Quebec premier Robert Bourassa to investigate the situation at the James Bay Project, Canada's largest hydroelectric project. Violence and dirty tactics had broken out as part of a union accreditation struggle. To ensure the commission was non-partisan, Bourassa, the Liberal premier, placed Robert Cliche, a former leader of the provincial New Democratic Party in charge. Cliche asked Mulroney, a Progressive Conservative and a former student of his, to join the commission. Mulroney asked Lucien Bouchard to join as counsel. The committee's proceedings, which showed Mafia infiltration of the unions, made Mulroney well known in Quebec, as the hearings were extensively covered in the media.[14] The Cliche Commission's report was largely adopted by the Bourassa government. A notable incident included the revelation that the controversy may have involved the office of the Premier of Quebec, when it emerged that Paul Desrochers, Bourassa's special executive assistant had met with the union boss André Desjardins, known as the "King of Construction", to ask for his help with winning a by-election in exchange guaranteeing that only companies employing workers from his union would work on the James Bay project.[15] Although Bouchard favoured calling in Robert Bourassa as a witness, Mulroney refused, deeming it a violation of 'executive privilege'.[3] Mulroney and Bourassa would later cultivate a friendship that would turn out to be extremely beneficial when Mulroney ran for re-election in 1988.

Loses first leadership race, 1975–76

The Stanfield-led Progressive Conservatives lost the 1974 election to the Pierre Trudeau-led Liberals, leading to Stanfield's resignation as leader. Mulroney, despite never having run for elected office, entered the contest to replace him. Mulroney and provincial rival Claude Wagner were both seen as potentially able to improve the party's standing in Quebec, which had supported the federal Liberals for decades. Mulroney had played the lead role in recruiting Wagner to the PC party a few years earlier, and the two wound up as rivals for Quebec delegates, most of whom were snared by Wagner, who even blocked Mulroney from becoming a voting delegate at the convention.[3] In the leadership race, Mulroney spent an estimated $500,000, far more than the other candidates, and earned himself the nickname 'Cadillac candidate'. At the 1976 leadership convention, Mulroney placed second on the first ballot behind Wagner. However, his expensive campaign, slick image, lack of parliamentary experience, and vague policy positions did not endear him to many delegates, and he was unable to build upon his base support, being overtaken by eventual winner Joe Clark on the second ballot. Mulroney was the only one of the eleven leadership candidates who did not provide full financial disclosure on his campaign expenses, and his campaign finished deeply in debt.[3] Following the convention, Mulroney turned down the offer of a shadow cabinet portfolio in Clark's caucus.

Business leadership

Mulroney took the job of executive vice president of the Iron Ore Company of Canada, a joint subsidiary of three major U.S. steel corporations. Mulroney earned a salary well into the six-figure range. In 1977, he was appointed company president. Drawing upon his labour law experience, he instituted improved labour relations, and, with commodity prices on the rise, company profits soared during the next several years. In 1983 Mulroney successfully negotiated the closing of the Schefferville mine, winning a generous settlement for the affected workers.[16] Under his leadership, the company was sold off to foreign interests. In the wake of his loss in the 1976 leadership race, Mulroney battled alcohol abuse and depression for several years; he credits his loyal wife Mila with helping him recover. In 1979, he permanently became a teetotaler. During his IOC term, he made liberal use of the company's executive jet, frequently flying business associates and friends on fishing trips.[3] Mulroney also maintained and expanded his extensive political networking among business leaders and conservatives across the country. As his business reputation grew, he was invited onto several corporate boards. He declined an offer to run in a Quebec by-election as a federal Liberal.

Party leader

Joe Clark led the Progressive Conservative party to a minority government in the 1979 federal election which ended 16 years of continuous Liberal rule. However, the government fell after a successful no-confidence motion over his minority government's budget in December 1979. The PCs subsequently lost the federal election held two months later to Trudeau and the Liberals. Many Tories were also annoyed with Clark over his slowness in dispensing patronage appointments after he became prime minister in June 1979. By late 1982, Joe Clark's leadership of the Progressive Conservatives was being questioned in many party circles and among many Tory members of Parliament, despite his solid national lead over Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in opinion polls, which stretched to 19 percent in summer 1982.

Mulroney on the floor of the 1983 leadership convention. Photograph by Alasdair Roberts.

Mulroney, while publicly endorsing Clark at a press conference in 1982, organized behind the scenes to defeat him at the party's leadership review. Clark's key Quebec organizer Rodrigue Pageau was in fact a double agent, working for Mulroney, undermining Clark's support.[3] When Clark received an endorsement by only 66.9 per cent of delegates at the party convention in January 1983 in Winnipeg, he resigned and ran to regain his post at the 1983 leadership convention. Despite still not being a member of Parliament, Mulroney ran against him, campaigning more shrewdly than he had done seven years before. Mulroney had been criticized in 1976 for lacking policy depth and substance, a weakness he addressed by making several major speeches across the country in the early 1980s, which were collected into a book, Where I Stand, published in 1983.[3] Mulroney also avoided most of the flash of his earlier campaign, for which he had been criticized. Mulroney was elected party leader on June 11, 1983, beating Clark on the fourth ballot, attracting broad support from the many factions of the party and especially from representatives of his native Quebec. Two months later, Mulroney entered Parliament as the MP for Central Nova in Nova Scotia, winning a by-election in what was then considered a safe Tory seat, after Elmer MacKay stood aside in his favour. This is a common practice in most parliamentary systems.

Throughout his political career, Mulroney's fluency in English and French, with Quebec roots in both cultures, gave him an advantage that eventually proved decisive.[3]

Because of health problems shortly after becoming party leader, Mulroney quit smoking in 1983.

By the start of 1984, as Mulroney began learning the realities of parliamentary life in the House of Commons, the Tories took a substantial lead in opinion polling. It was almost taken for granted that Trudeau would be heavily defeated by Mulroney in the general election due no later than 1985. Trudeau announced his retirement in February, and the Liberal Party chose John Turner, previously the Minister of Finance under Trudeau in the 1970s, as its new leader. The Liberals then surged in the polls, to take a lead, after trailing by more than 20 percentage points. Only four days after being sworn in as Prime Minister, Turner called a general election for September. In so doing, he had to postpone a planned Canadian summer visit by Queen Elizabeth II, who makes it her policy to not travel abroad during foreign election campaigns. But the Liberal election campaign machinery was in disarray, leading to a weak campaign.[17]

The campaign is best remembered for Mulroney's attacks on a raft of Liberal patronage appointments. In his final days in office, Trudeau had controversially appointed a flurry of Senators, judges, and executives on various governmental and crown corporation boards, widely seen as a way to offer 'plum jobs' to loyal members of the Liberal Party. Upon assuming office, Turner, who had been out of politics for nine years while he earned a lucrative salary as a Toronto lawyer, showed that his political instincts had diminished. He had been under pressure to advise Governor General Jeanne Sauvé to cancel the appointments—which convention would then have required Sauvé to do. However, Turner chose not to do so, and instead proceeded to appoint several more Liberals to prominent political offices per a signed, legal agreement with Trudeau.[18]

Ironically, Turner had planned to attack Mulroney over the patronage machine that the latter had set up in anticipation of victory. In a televised leaders' debate, Turner launched what appeared to be the start of a blistering attack on Mulroney by comparing his patronage machine to that of the old Union Nationale in Quebec. However, Mulroney successfully turned the tables by pointing to the recent raft of Liberal patronage appointments.[19] He demanded that Turner apologize to the country for making "these horrible appointments." Turner replied that "I had no option" except to let the appointments stand. Mulroney famously responded:

"You had an option, sir. You could have said, 'I am not going to do it. This is wrong for Canada, and I am not going to ask Canadians to pay the price.' You had an option, sir—to say 'no'—and you chose to say 'yes' to the old attitudes and the old stories of the Liberal Party. That, sir, if I may say respectfully, is not good enough for Canadians."[19]

Turner froze and wilted under this withering riposte from Mulroney.[19] He could repeat only, "I had no option." A visibly angry Mulroney called this "an avowal of failure" and "a confession of non-leadership." The exchange led most papers the next day, with most of them paraphrasing Mulroney's counterattack as "You had an option, sir—you could have said 'no.'" Many observers believe that at this point, Mulroney assured himself of becoming prime minister.[19]

On September 4, Mulroney and the Tories won the largest majority government in Canadian history. They took 211 seats, three more than their previous record in 1958. The Liberals won only 40 seats, which, at the time was their worst performance ever and the worst defeat for a governing party at the federal level in Canadian history. The Conservatives won just over half of the popular vote (compared to 53.4 percent in 1958) and led in every province, emerging as a national party for the first time since 1958. Especially important was the Tories' performance in Mulroney's home province, Quebec. The Tories had only won the most seats in that province once since 1896 – the 1958 Tory landslide. However, largely due to anger at Trudeau, and Mulroney's promise of a new deal for Quebec, the province swung over dramatically to support him. The Tories had only won one seat out of 75 in 1980 but took 58 seats in 1984. Mulroney yielded Central Nova back to MacKay and instead ran in the eastern Quebec riding of Manicouagan, which included Baie-Comeau.

In 1984, the Canadian Press named Mulroney "Newsmaker of the Year" for the second straight year, making him only the second prime minister to have received the honour both before becoming prime minister and when prime minister (the other being Lester Pearson).

Prime minister (1984–1993)

First mandate (1984–1988)

Mila (left) and Brian (right) Mulroney greet Rt. Hon. Pierre Trudeau (Foreground).

The first Conservative majority government in 26 years—and only the second in 54 years—initially seemed to give Mulroney a very formidable position. The Tories had won just over half the popular vote, and no other party crossed the 50-seat mark. On paper, he was free to take Canada in any direction he wanted. However, his position was far more precarious than his parliamentary majority would suggest. His support was based on a 'grand coalition' of socially conservative populists from the West, Quebec nationalists, and fiscal conservatives from Ontario and Atlantic Canada. Such diverse interests became difficult for Mulroney to juggle.[20]

He attempted to appeal to the Western provinces, whose earlier support had been critical to his electoral success, by cancelling the National Energy Program and including a large number of Westerners in his Cabinet (including Clark as minister of external affairs). However, he was not completely successful, even aside from economic and constitutional policy. For example, he moved CF-18 servicing from Manitoba to Quebec in 1986, even though the Manitoba bid was lower and the company was better rated,[21] and received death threats for exerting pressure on Manitoba over French language rights.[22]

Many of Mulroney's ministers had little government experience, resulting in conflicts of interest and embarrassing scandals. Many Tories expected patronage appointments due to the long time out of government.[23] Indeed, Mulroney made a number of unscripted gaffes regarding patronage, including the reference to Ambassador Bryce Mackasey as "there's no whore like an old whore".[24] The new Prime Minister's handlers were concerned by apparent unpredictability and rumours of drinking.

Mila (left) and Brian (right) Mulroney at Andrews Air Force Base in September 1984

One of Mulroney's main priorities was to lower the deficit, which had increased from $1 billion under Lester B. Pearson to $32.4 billion under Pierre Eliott Trudeau. However, the country's annual deficit increased during Mulroney's term from $32.4 billion to $39 billion.[25] His attempts to reduce spending limited his ability to deliver on many promises. Also impeding his progress was the Senate, where the Liberals had a large majority due to their previous long tenure in power. Led by Allan MacEachen, the Senate took a very assertive role in legislation, forcing the government to compromise on several points despite its considerable House majority.

A major undertaking by Mulroney's government was an attempt to resolve the divisive issue of national unity. Quebec was the only province that did not sign the new Canadian constitution negotiated by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in 1982, and Mulroney wanted to include Quebec in a new agreement with the rest of Canada. In 1987, he negotiated the Meech Lake Accord with the provincial premiers, a package of constitutional amendments designed to satisfy Quebec's demand for recognition as a "distinct society" within Canada, and to devolve some powers to the provinces.

The Mulroneys with President and Mrs. Reagan in Quebec, Canada, March 18, 1985, the day after the famous "Shamrock Summit", when the two leaders sang "When Irish Eyes are Smiling."

Another of Mulroney's priorities was the privatization of many of Canada's crown corporations. In 1984, the Government of Canada held 61 crown corporations.[26] It sold off 23 of them including Air Canada which was completely privatized by 1989, although the Air Canada Public Participation Act[27] continued to make certain requirements of the airline. Petro-Canada was also later privatized.

The Air India Flight 182 bombing, which originated in Montreal, happened during Mulroney's first term. This was the largest terrorist act before September 11, 2001, with the majority of the 329 victims being Canadian citizens. Mulroney sent a letter of condolence to then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, which sparked an uproar in Canada since he did not call families of the actual victims to offer condolences. Gandhi replied that he should be the one providing condolences to Mulroney, given that the majority of victims were Canadian or lived in Canada. Many Indo-Canadians considered this to be a racist act because they felt Mulroney did not consider them to be true Canadian citizens as they were not of European descent.[citation needed] Furthermore, there were several warnings from the Indian government to the Mulroney government about terrorist threats towards Air India flights. Questions remain as to why these warnings were not taken more seriously and whether the events leading to the bombing could have been prevented.[28][29][30] The Governor General-in-Council in 2006 appointed the former Supreme Court Justice John Major to conduct a commission of inquiry. His report was completed and released on 17 June 2010.

Near the end of his first term, Mulroney gave a formal apology and a $300 million compensation package to the families of the 22,000 Japanese Canadians who had been divested of their property and interned during World War II.

Foreign policy

Mulroney's government opposed the apartheid regime in South Africa and he met with many of the regime's opposition leaders throughout his tenure. His position put him at odds with the American and British governments, but also won him respect elsewhere. Also, external affairs minister Joe Clark was the first foreign affairs minister to land in previously isolated Ethiopia to lead the Western response to the 1984–1985 famine in that country; Clark landed in Addis Ababa so quickly he had not even seen the CBC report that had created the initial and strong public reaction. Canada's response was overwhelming and led the U.S.A. and Britain to follow suit almost immediately — an unprecedented situation in foreign affairs at that time, since Ethiopia had a Marxist regime and had previously been isolated by Western governments.

The Mulroney government also took a strong stand against the U.S. intervention in Nicaragua under Reagan, and accepted refugees from El Salvador, Guatemala, and other countries with repressive regimes supported directly by the Reagan administration.

Free trade

During his tenure as prime minister, Brian Mulroney's close relationship with U.S. President Ronald Reagan helped secure a landmark treaty on acid rain and the ratification of a free-trade treaty with the United States under which all tariffs between the two countries would be eliminated by 1998.[31]

Critics noted that Mulroney had originally professed opposition to free trade during the 1983 leadership campaign.[32] Though the 1985 report of the MacDonald Commission suggeted free trade as one of the idea to him.[33] This agreement was controversial, and the Senate demanded an election before proceeding to a ratification vote. The Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement was the central issue of the 1988 election, with the Liberals and NDP opposing it.With the Liberals gaining the initial momentum, a successful counterattack by Allan Gregg resulted in the PCs being re-elected with a solid but reduced majority and 43 percent of the popular vote. In addition,the trade deal gain the support of future Quebec Premiers Jacques Parizeau and Bernard Landry, which helped Mulroney to maintain their standing in Quebec.[34] Thus he became the only Canadian Conservative party leader in the 20th century to lead his party to consecutive majority governments during peacetime. In this election, Mulroney transferred to another eastern Quebec seat, Charlevoix, after an electoral redistribution saw its boundary shift to include Baie-Comeau.

Although most Canadians voted for parties opposed to free trade, the Tories were returned with a majority government, and implemented the deal.

On election day, November 21, 1988, Mulroney made a controversial order in council which allowed the establishment of the AMEX Bank of Canada (owned by American Express).

Second mandate (1988–1993)

Mulroney's second term was marked by an economic recession. He proposed the introduction of a national sales tax, the Goods and Services Tax (GST), in 1989. When it was introduced in 1991, it replaced the Manufacturers' Sales Tax (MST) that had previously been applied at the wholesale level on goods manufactured in Canada. A bitter Senate battle ensued, and many polls showed that as many as 80% of Canadians were opposed to the tax. Mulroney had to use Section 26 (the Deadlock Clause), a little known Constitutional provision, allowing him in an emergency situation to ask the Queen to appoint 8 new Senators. Although the government argued that the tax was not a tax increase, but a tax shift, the highly visible nature of the tax was extremely unpopular, and many resented Mulroney's use of an "emergency" clause in the constitution.[35]

The Meech Lake Accord also met its doom in 1990. It was not ratified by the provincial governments of Manitoba and Newfoundland before the June ratification deadline. This failure sparked a revival of Quebec separatism,[36] and led to another round of meetings in Charlottetown in 1991 and 1992. These negotiations culminated in the Charlottetown Accord, which outlined extensive changes to the constitution, including recognition of Quebec as a distinct society. However, the agreement was overwhelmingly defeated in a national referendum in October 1992. Many blamed the GST battle and Mulroney's unpopularity for the fall of the Accord.[37]

In 1990 Mulroney nominated Ray Hnatyshyn, an MP from Saskatoon and a former Cabinet minister, to be Governor General (1990–1995).

On December 2, 1991, Canada became the first Western nation to recognize Ukraine as an independent country, next day after the landslide referendum in favor of independence in Ukraine.

NAFTA Initialing Ceremony, October 1992; From left to right: (Standing) Mexican President Salinas, US President Bush, Prime Minister Mulroney, (Seated) Jaime Serra Puche, Carla Hills, Michael Wilson.

The worldwide recession of the early 1990s significantly damaged the government's financial situation. Mulroney's inability to improve the government's finances, as well as his use of tax increases to deal with it, were major factors in alienating the western conservative portion of his power base – this contrasted with his tax cuts earlier as part of his 'pro-business' plan which had increased the deficit. At the same time, the Bank of Canada began to raise interest rates in order to meet a zero inflation target; the experiment was regarded as a failure that exacerbated the effect of the recession in Canada. Annual budget deficits ballooned to record levels, reaching $42 billion in his last year of office. These deficits grew the national debt dangerously close to the psychological benchmark of 100% of GDP, further weakening the Canadian dollar and damaging Canada's international credit rating.[37]

Mulroney supported the United Nations coalition during the 1991 Gulf War and when the UN authorized full use of force in the operation, Canada sent a CF-18 squadron with support personnel and a field hospital to deal with casualties from the ground war as well as a company of The Royal Canadian Regiment to safeguard these ground elements calling Canada's participation Operation Friction. In August he sent the destroyers HMCS Terra Nova and HMCS Athabaskan to enforce the trade blockade against Iraq. The supply ship HMCS Protecteur was also sent to aid the gathering coalition forces. When the air war began, Canada's planes were integrated into the coalition force and provided air cover and attacked ground targets. This was the first time since the fighting on Cyprus in 1974 that Canadian forces participated directly in combat operations.

For the Canadian Forces, the Mulroney years began with hope but ended with disappointment. Most members of the CF welcomed the return to distinctive uniforms for the three services, replacing the single green uniform worn since unification (1967–70). A White Paper proposed boosting the CF's combat capability, which had, according to Canadian Defence Quarterly, declined so badly that Canada would have been unable to send a brigade to the Gulf War had it desired to. The CF in this period did undergo a much-needed modernization of a range of equipment from trucks to a new family of small arms. Many proposed reforms, however, failed to occur, and according to historian J.L. Granatstein, Mulroney "raised the military's hopes repeatedly, but failed to deliver." In 1984, he had promised to increase the military budget and the regular force to 92,000 troops, but the budget was cut and the troop level fell to below 80,000 by 1993. This was, however, in step with other NATO countries after the end of the Cold War.[38] The Mulroney government undertook a defence policy review, publishing a new statement in late 1991, but political considerations meant that no comprehensive policy for the post Cold War era was arrived at before the government's defeat in 1993. According to Granatstein, this meant that Canada was not able to live up to its post-Cold War military commitments.

The decline of cod stocks in Atlantic Canada led the Mulroney government to impose a moratorium on the cod fishery there, putting an end to a large portion of the Newfoundland fishing industry, and causing serious economic hardship. The government instituted various programmes designed to mitigate these effects but still became deeply unpopular in the Atlantic provinces.

The environment was a key focus of Mulroney's government, as Canada became the first industrialized country to ratify both the biodiversity convention and the climate change convention agreed to at the UN Conference on the Environment. His government added significant new national parks (Bruce Peninsula, South Moresby, and Grasslands), and passed the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act and Canadian Environmental Protection Act.[37]

In 1991, Frank magazine ran a satirical advertisement for a contest inviting young Tories to "Deflower Caroline Mulroney". Her father was incensed and threatened physical harm toward those responsible before joining several women's groups in denouncing the ad as an incitement to rape on national television. Frank's editor Michael Bate, called the spoof, intended to mock her unpopular father for bringing her to public adult oriented events, "clumsy" but had no regrets. Bate also shared sympathy towards her father's reaction over the spoof.[39]

Retirement

Widespread public resentment of the Goods and Services Tax, an economic slump, the fracturing of his political coalition, and his lack of results regarding the Quebec situation caused Mulroney's popularity to decline considerably during his second term. An ominous sign was a 1989 by-election in the Alberta riding of Beaver River. In this election, called when Tory MP John Dahmer died before ever having a chance to attend a sitting, Reform Party candidate Deborah Grey won by a hefty 4,200 votes after finishing fourth in the general election just five months earlier. This was perhaps, the first sign that Mulroney's grand coalition was fracturing; the PCs had dominated Alberta's federal politics since the 1968 election. Another sign came before Meech Lake was finalized, when Bouchard resigned from both the cabinet and the party over changes to the proposal that he felt diluted its spirit. After the failure of Meech, Bouchard convinced several other Tories to break with the party and join him to form the Bloc Québécois, a pro-sovereigntist (i.e. independentist) party. Years later, Mulroney said that his biggest error as Prime Minister had been trusting his former university friend; indeed, he and Bouchard have not spoken to each other in over two decades.[40]

Mulroney entered 1993 facing a statutory general election (under Canadian law, federal governments can have a maximum duration of five years, but they often have lesser duration as they must enjoy the confidence of the House of Commons in order to continue in office). By this time, his approval ratings had dipped into the teens, and were at 11% in a 1992 Gallup poll, making him one of the most unpopular prime ministers since opinion polling began in Canada in the 1940s.[41] There was a consensus that Mulroney would be heavily defeated by Jean Chrétien and the Liberals if he led the Tories into the next election—ironically, the same situation that led to Trudeau's departure from the scene nine years earlier. He announced his retirement from politics in February and was replaced as Prime Minister by Defence Minister Kim Campbell in June. The last Gallup Poll taken before his retirement, in February 1993, showed his approval ratings had rebounded to 21%.[42]

In his final days in office, Mulroney made several decisions that hampered the Tory campaign later that year. He took a lavish international "farewell" tour[43] mostly at taxpayers' expense, without transacting any official business. Also, by the time he handed power to Campbell, there were only two-and-a-half months left in the Tories' five-year mandate. Further compounding the problem, Mulroney continued to live at 24 Sussex Drive for some time after Campbell was sworn in as Prime Minister. Brian and Mila Mulroney's new private residence in Montreal was undergoing renovations, and they did not move out of 24 Sussex until their new home was ready. Instead, Campbell took up residence at Harrington Lake, the Prime Minister's official summer retreat across the river in Gatineau Park, Quebec.

The 1993 election was a disaster for the Tories. The oldest party in Canada was reduced from a majority with 151 seats to two seats in the worst defeat ever suffered for a governing party at the federal level. The 149-seat loss far exceeded the 95-seat loss the Liberals suffered in 1984. The Tories were no longer recognized as an official caucus in the House of Commons, since the required minimum number of seats for official party status is 12. As an example of the antipathy toward Mulroney, his former riding fell to the Bloc by a lopsided margin; the Tory candidate finished a distant third, with only 6,800 votes—just a few votes shy of losing his electoral deposit.[44] In her memoirs, Time and Chance, and in her response in the National Post to The Secret Mulroney Tapes, Campbell said that Mulroney left her with almost no time to salvage the Tories' reputation once the bounce from the leadership convention wore off. Campbell went as far as to claim that Mulroney knew the Tories would be defeated regardless of who led them into the election, and wanted a "scapegoat who would bear the burden of his unpopularity" rather than a true successor.

Airbus/Schreiber affair

On September 29, 1995, the Canadian Department of Justice, acting on behalf of the RCMP, sent a Letter of Request to the Swiss Government asking for information related to allegations that Mulroney was involved in a criminal conspiracy to defraud the Government of Canada.[45]

The investigation pertained to “improper commissions” allegedly paid to German-Canadian businessman Karlheinz Schreiber (or to companies controlled by him), Brian Mulroney and former Newfoundland premier Frank Moores in exchange for three government contracts.[46]

These contracts involved the purchase of Airbus Industrie aircraft by Air Canada; the purchase of helicopters by the Canadian Coast Guard from Messerschmitt-Bolkow-Blohm GmbH (MBB) in 1986; and the establishment of a manufacturing plant for Thyssen Light Armoured Vehicles (Bear Head Project) in the province of Nova Scotia, a project which Mulroney as prime minister had cancelled.[46]

This Letter of Request (LOR) “and its contents were to be kept confidential” but the letter was leaked to the media.[47] As a result, Mulroney launched a $50 million libel lawsuit against the Government of Canada and the RCMP on November 20, 1995.[48] On January 5, 1997, Mr. Mulroney agreed to an out-of-court settlement with the Government of Canada and the RCMP.[49]

After politics

Since leaving office, Mulroney has served as an international business consultant and remains a partner with the law firm Ogilvy Renault. He currently sits on the board of directors of multiple corporations, including Barrick Gold, Quebecor Inc., Archer Daniels Midland, TrizecHahn Corp. (Toronto), Cendant Corp. (New York), AOL Latin America, Inc. (New York) and Cognicase Inc. (Montreal). He is a senior counselor to Hicks, Muse, Tate & Furst, a global private equity fund in Dallas, chairman of Forbes Global (New York), and was a paid consultant and lobbyist for Karl-Heinz Schreiber beginning in 1993. He is also chairman of various international advisory boards and councils for many international companies, including Power Corp. (Montreal), Bombardier (Montreal), the China International Trust and Investment Corp. (Beijing), J.P. Morgan Chase and Co. (New York), Violy, Byorum and Partners (New York), VS&A Communications Partners (New York), Independent Newspapers (Dublin) and General Enterprise Management Services Limited (British Virgin Islands).[50]

In 1998, Mulroney was accorded Canada's highest civilian honour when he was made a Companion of the Order of Canada.

At the funeral of Ronald Reagan with former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev, former Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone and former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

In 2003, Mulroney received the Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars of the Smithsonian Institution at a ceremony in Montreal. The award was in recognition of his career in politics.

In January 2004, Mulroney delivered a keynote speech in Washington, D.C. celebrating the tenth anniversary of the North American Free Trade Agreement. In June 2004, Mulroney presented a eulogy for former U.S. President Ronald Reagan during the latter's state funeral. Mulroney and former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher were the first foreign dignitaries to eulogize at a funeral for an American president. Two years later, at the request of Prime Minister Stephen Harper, Mulroney traveled to Washington, DC along with Michael Wilson, Canada's ambassador to the United States, as Canada's representatives at the state funeral of former president Gerald Ford.

In February 2005, as part of a physical examination, a CT scan revealed two small lumps in one of Mulroney's lungs. In his youth, Mulroney had been a heavy smoker. His doctors performed a biopsy, which ruled out cancer. (His surgery is sometimes cited as an example of the dangers of unnecessary testing.)[51] He recovered well enough to tape a speech for the Conservative Party of Canada's 2005 Policy Convention in Montreal in March, though he could not attend in person. He later developed pancreatitis and he remained in hospital for several weeks. It was not until April 19 that his son, Ben Mulroney, announced he was recovering and would soon be released.[citation needed]

On September 12, 2005, veteran writer and former Mulroney confidant Peter C. Newman released The Secret Mulroney Tapes: Unguarded Confessions of a Prime Minister. Based in large part on remarks from the former prime minister which Newman had taped with Mulroney's knowledge, the book set off national controversy. Newman had been given unfettered access to Mulroney for a thorough biography, and claims Mulroney did not honour an agreement to allow him access to confidential papers.[52] After the falling out, Mulroney began work on his autobiography, without Newman's help. Mulroney himself has declared that he showed poor judgement in making such unguarded statements, but he says that he will have to live with it.

This led Mulroney to respond at the annual Press Gallery Dinner, which is noted for comedic moments, in Ottawa, October 22, 2005. The former Prime Minister appeared on tape and very formally acknowledged the various dignitaries and audience groups before delivering the shortest speech of the night: "Peter Newman: Go fuck yourself. Thank you ladies and gentlemen, and good night."[53]

Thirteen years after leaving office, Mulroney was named the "greenest" Prime Minister in Canadian history by a 12-member panel at an event organized by Corporate Knights magazine.[54]

In 2014, Mulroney became the chairman of Quebecor and defused tensions resulting from the continuing influence of former President and CEO Pierre Karl Péladeau.[55]

Current political affiliation

Mulroney joined the Conservative Party of Canada following its creation in 2003 by the merger of the Progressive Conservatives and the Canadian Alliance. According to press reports his membership lapsed in 2006. In early 2009, Mulroney "called a high-ranking person in the party and asked that his name be removed from all party lists" due to his anger at the continued inquiry into his financial affairs,[56] although he denies this claim.[57]

Legacy

Mulroney's legacy is complicated and even emotional. Mulroney makes the case that his once-radical policies on the economy and free trade were not reversed by subsequent governments, and regards this as vindication.[58] His Deputy Prime Minister Don Mazankowski said that his greatest accomplishment will be seen as, "Dragging Canada kicking and screaming into the 21st century." Mulroney's legacy in Canada is associated mostly with the 1988 Free Trade Agreement[32] and the Goods and Services Tax (GST).

Although the Tories were re-elected in 1988 campaigning on free trade, they won with only 43% of the popular vote, compared to 52% of the vote which went to the Liberals and the New Democratic Party who campaigned mostly against the agreement. However, when the Liberals under Jean Chrétien came to office in 1993 promising to re-negotiate key parts of the agreement, they continued the deal with only slight changes, and signed the North American Free Trade Agreement which expanded the free trade area to include Mexico.

The visibility of the GST proved to be very unpopular. The GST was created to help eliminate the ever-growing deficit and to replace the hidden Manufacturer's sales tax, which Mulroney argued was hurting business. Mulroney's usage of a rare Constitutional clause to push the tax through,[59] prices not falling very much with the MST removed, and the "in your face" nature of the tax infuriated politicians and the public. The succeeding Liberal government of Jean Chrétien campaigned in 1993 on a promise to eliminate the GST (as per the Red Book), but ultimately backed away from that promise. This prompted two of their members Sheila Copps and John Nunziata to resign or be expelled in protest. Mulroney's supporters argue that the GST helped the subsequent government eliminate the deficit, and that the visible nature of the tax kept politicians more accountable.

Mulroney's intense unpopularity at the time of his resignation led many Conservative politicians to distance themselves from him for some years. His government had flirted with 10 percent approval ratings in the early 1990s, when Mulroney's honesty and intentions were frequently questioned in the media, by Canadians in general and by his political colleagues.[60] During the 1993 election, the Progressive Conservative Party was reduced to just two seats, which was seen as partially due to a backlash against Mulroney, as well as due to the fracturing of his "Grand Coalition".

Social conservatives found fault with Mulroney's government in a variety of areas. These include Mulroney's opposition to capital punishment[22] and an attempted compromise on abortion.[61]Fiscal conservatives likewise didn't appreciate his tax increases and his failure to curtail expansion of "big government" programs and political patronage.

In the 1993 election, nearly all of the Tories' Western support transferred into Reform, which replaced the PCs as the major right-wing force in Canada. The Tories only won two seats west of Quebec in the next decade and recovered only upon reunification the elements that had split from the party in the late 1980s. The Canadian right was not reunited until they merged with Reform's successor, the Canadian Alliance, in December 2003 to form the new Conservative Party of Canada. Mulroney played an influential role by supporting the merger at a time when former PC leaders Joe Clark, Jean Charest and Kim Campbell either opposed it or expressed ambivalence.

Military historians Norman Hillmer and J.L. Granatstein ranked Mulroney eighth among Canada's prime ministers in their 1999 book Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders.

On March 31, 2009 it was reported by various news outlets that a Conservative official claimed Mulroney was no longer a member of the party. They claimed his membership expired in 2006 and was not renewed. Additionally, Mulroney allegedly "called a senior party official two months ago to ask that his name be pulled off all party lists and materials and that communications with him cease." However, a Mulroney confidante, speaking on condition of anonymity, called the party's claims preposterous. 'He's part of the history of this party, you can't rewrite history. If they're worried about branding, then shut the inquiry down. They're the ones who called the inquiry.' "[62]

Memoir

Mulroney appears during an interview with Heather Reisman, speaking about his memoirs.

Mulroney's Memoirs: 1939–1993 was released on September 10, 2007. Mulroney criticizes Trudeau for avoiding military service in World War II, and favourably references sources that describe the young Trudeau as holding anti-Semitic nationalist views and having an admiration for fascist dictators.[63][64]Tom Axworthy, a prominent Liberal strategist, responded that Trudeau should be judged on his mature views. Historian and former MP and Trudeau biographer John English said "I don't think it does any good to do this kind of historical ransacking to try to destroy reputations".[65][66]

An earlier book expressing Brian Mulroney's own opinions and aims, is Where I Stand (McClelland and Stewart, Toronto, 1983), which, on its front paperback cover, emblazons the words "The new Tory leader speaks out".

Honours

According to Canadian protocol, as a former Prime Minister, he is styled "The Right Honourable" for life.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

| Ribbon | Description | Notes |

| Companion of the Order of Canada (C.C.) |

| |

| Grand Officer of the Ordre national du Québec |

| |

| 125th Anniversary of the Confederation of Canada Medal |

| |

Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal for Canada |

| |

Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal for Canada |

| |

| Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Kniaz Yaroslav the Wise (Ukraine) |

| |

| Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (Japan) |

| |

Supreme Companion of O. R. Tambo (Gold) (South Africa) |

| |

| Commander of the National Order of the Legion of Honour (France) |

|

Honorary degrees

Brian Mulroney has received several honorary degrees, including:

| Location | Date | School | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 1980 | Memorial University of Newfoundland | Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[73] | |

| 21 May 1992 | Johns Hopkins University | Doctor of Humane Letters (DHL) [74] | |

| 26 April 1994 | Central Connecticut State University | Doctor of Social Science (D.S.Sc) | |

| May 1998 | University of Missouri–St. Louis | Doctor of Laws(LL.D) [75] | |

| December 2005 | Concordia University | Doctor of Laws (LL.D) [76] | |

| 21 May 2007 | Boston College | Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[77] | |

| 15 June 2007 | University of Western Ontario | Doctor of Laws (LL.D) [78] | |

| 16 June 2007 | Laval University | ||

| 3 May 2015 | St. Francis Xavier University | [79] | |

| 15 May 2018 | St. Thomas University | Doctorate [80] |

Order of Canada Citation

Brian Mulroney was appointed a Companion of the Order of Canada on May 6, 1998. His citation reads:[81]

As the eighteenth Prime Minister of Canada, he led the country for nine consecutive years. His accomplishments include, among others, the signing of the Free Trade Agreement with the United States, the North American Free Trade Agreement with Mexico and the United States, and the Acid Rain Treaty. In other international activities, he assumed the leadership of the Commonwealth countries against apartheid in South Africa and was appointed Co-chair of the United Nations' World Summit for Children. Fiscal reform, important environmental initiatives and employment equity were also highlights of his political career.

Supreme Court appointments

Mulroney chose the following jurists to be appointed by the Governor General as Governor-General-in-Council/Governor-in-Council to be Puisne Justices of the

Supreme Court of Canada (and two subsequently were elevated to Chief Justice of Canada):

Gerard La Forest (January 16, 1985 – September 30, 1997)

Claire L'Heureux-Dubé (April 15, 1987 – July 1, 2002)

John Sopinka (May 24, 1988 – November 24, 1997)

Charles Gonthier (February 1, 1989 – August 1, 2003)

Peter Cory (February 1, 1989 – June 1, 1999)

Beverley McLachlin (March 30, 1989 – December 15, 2017, as Chief Justice from January 7, 2000)

Antonio Lamer (as Chief Justice, July 1, 1990 – January 6, 2000; appointed a Puisne Justice under Prime Minister Trudeau, March 28, 1980)

William Stevenson (September 17, 1990 – June 5, 1992)

Frank Iacobucci (January 7, 1991 – June 30, 2004)

John C. Major (November 13, 1992 – December 25, 2005)

Notable cabinet ministers

|

|

Arms

|

|

See also

- List of Canadian Prime Ministers

- Mulroney: The Opera

- Shamrock Summit

References

^ "Parliament of Canada". .parl.gc.ca. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ "School of Canadian Irish Studies – Irene Mulroney Scholarship". Cdnirish.concordia.ca. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ abcdefghijklm Mulroney: The Politics of Ambition, by John Sawatsky, 1991

^ Peter C. Newman, The Secret Mulroney Tapes: Unguarded Confessions of a Prime Minister. Random House Canada, 2005, p. 54.

^ Gordon Donaldson, The Prime Ministers of Canada, (Toronto: Doubleday Canada Limited, 1997), p. 309.

^ ab Donaldson, p. 310.

^ "SAN Dnevne novine". San.ba. 2008-03-14. Retrieved 2010-06-07. [dead link]

^ "Caroline Mulroney named Ontario PC candidate in York-Simcoe riding". The Globe and Mail. 2017-09-10. Retrieved 2018-05-02.

^ "MEET THE MULRONEYS". Retrieved 2018-05-02.

^ The Politics of Ambition, by John Sawatsky, 1991

^ H. Graham Rawlinson and J.L. Granatstein, The Canadian 100: The 100 Most Influential Canadians of the 20th century, Toronto: McArthur & Company, 1997, pp. 19–20.

^ The Politics of Ambition, by John Sawatsky, 1991, pp. 129–135

^ "Stanley Hartt, 80, was 'an articulate advocate for Canada'". Retrieved 2018-05-04.

^ ab Jim Lotz, Prime Ministers of Canada, Bison Books, 1987, p. 144.

^ Sawatsky, John Mulroney: the politics of ambition, Toronto: Mcfarlane Walter & Ross, 1991 page 257.

^ "Private life after public loss – Television – CBC Archives". CBC News.

^ The Insiders: Government, Business, and the Lobbyists, by John Sawatsky, 1987

^ Donaldson, p. 320; Newman, p. 71.

^ abcd Newman, pp. 71–72.

^ David Bercuson et al. Sacred Trust? Brian Mulroney and the Conservative Party in Power (1987)

^ Newman, p. 116.

^ ab Newman, p. 427.

^ Newman, p. 91, quoting "Mulroney's friend Arthur Campeau."

^ Hamovitch, Eric, Rae Murphy, Robert Chodos. Selling Out: Four Years of the Mulroney Government, 1988. Page 115.

^ "Canada's deficits and surpluses, 1963-2014". CBC. 18 Mar 2014.

^ "Lessons from the North: Canada's Privatization of Military Ammunition Production" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ "Air Canada Public Participation Act". Laws.justice.gc.ca. 2010-05-31. Archived from the original on 2013-05-07. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

^ "story". Canada.com. 2006-06-19. Archived from the original on 2012-11-09. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ "ctv story". Ctv.ca. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ "CBC website November 7, 2007". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The Canadian Press. 2006-11-07. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ Stephen Clarkson. Canada and the Reagan Challenge: Crisis and Adjustment, 1981–85 (2nd ed. 1985) ch 5, 8

^ ab Donaldson, p. 334.

^ Banting, Keith G. "Royal Commission on Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-05-05.

^ "Parti Québécois the author of its own misfortune: Hébert | The Star". thestar.com. Retrieved 2018-05-05.

^ Raymond B. Blake, ed., Transforming the Nation: Canada and Brian Mulroney (2007)

^ Rawlinson and Graham, p. 22.

^ abc Blake, ed., Transforming the Nation: Canada and Brian Mulroney (2007)

^ "Defence Policy Review (MR-112E)". Parl.gc.ca. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ Trueheart, Charles (1993-07-05). "TO BE PERFECTLY FRANK ..." Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-05-02.

^ "Lucien Bouchard says 'wounds' remain with Brian Mulroney". CBC. The Canadian Press. August 21, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

^ Russell Ash, The Top 10 of Everything 2000, Montreal: The Reader's Digest Association (Canada) Ltd., 1999, p. 80.

^ "Home | Waterloo News". Newsrelease.uwaterloo.ca. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

^ Donaldson, p. 349.

^ "1993 Canadian Federal Election Results (Detail)". Esm.ubc.ca. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ "Mulroney Launches Suit". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

^ ab "Government of Canada website – Oliphant Commission p. 54" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-05. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

^ Government of Canada website – Oliphant Commission Executive Summary p. 3

^ "Superior Court exhibit" (PDF). William Kaplan. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

^ "Mulroney Wins Apology". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

^ "Mulroney-Harper alliance bad news for Canada's workers". Nupge.ca. 2004-06-23. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ A Check on Physicals, By JANE E. BRODY, The New York Times, January 21, 2013

^ Newman, p. 50.

^ "Video of Brian Mulroney's speech to the Press Gallery Dinner". YouTube. 2006-12-12. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ "Mulroney praised for his green record as PM". CTV.ca. 2006-04-20. Archived from the original on 2007-10-23. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ "Péladeau's political exit raises questions for Quebecor". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2016-05-04.

^ Mulroney not a Tory any more? Archived 2009-04-04 at the Wayback Machine., Campbell Clark, The Globe and Mail, April 1, 2009

^ Ignatieff has 'no moral compass,' PM says Archived 2009-04-11 at the Wayback Machine., Brian Laghi, The Globe and Mail, April 8, 2009

^ Newman, p. 361.

^ Donaldson, p. 344.

^ Donaldson, p. 327.

^ Donaldson, p. 356.

^ Tories, Mulroney in tiff over party membership[permanent dead link]. March 31, 2009, CTV.ca

^ "Mulroney slams Trudeau as lacking moral fibre to lead". CBC News. September 5, 2007.

^ Post, National (2007-09-05). "National Post: Repairing Trudeau's mistakes". Canada.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ Reuters: Mulroney lashes Trudeau, calls him a coward[permanent dead link]Archived copy at WebCite (June 28, 2007).

^ [1][dead link]

^ "The Governor General of Canada > Find a Recipient". Gg.ca. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

^ abc "Commemorative Medals of The Queen's Reign in Canada". Dominionofcanada.com. 2011-12-10. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

^ "Embassy of Ukraine in Canada – Publications". Mfa.gov.ua. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

^ "Investiture Ceremony for the Right Honourable Brian Mulroney, PC, CC, GOQ". Embassy of Japan in Canada. 2011.

^ "Brian Mulroney honoured with the order of the companions of or tambo in south africa". Norton Rose Fulbright. 2015-04-20. Retrieved 2015-05-21.

^ "AWARDS TO CANADIANS". 2016-11-26. Retrieved 2016-12-20.

^ (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20160215162823/http://www.mun.ca/senate/honorary_degrees_by_convo.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2015. Missing or empty|title=(help)

^ "Honorary Degrees Awarded (Alphabetical Order) | Johns Hopkins University Commencement". Web.jhu.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

^ "Honorary Degree Recipients". Umsl.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

^ "Honorary Degree Citation – Brian Mulroney | Concordia University Archives". Archives.concordia.ca. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

^ "@BC » Feature Archive » 2007 honors". At.bc.edu. 2007-05-16. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

^ "The University of Western Ontario : Honorary Degrees Awarded, 1881 – present" (PDF). Uwo.ca. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

^ "StFX celebrates Class of 2015, former Canadian Prime Minister delivers address to graduates | St. Francis Xavier University". Stfx.ca. 2015-05-03. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

^ http://w3.stu.ca/stu/News/161090

^ "Order of Canada". Archive.gg.ca. 2009-04-30. Retrieved 2012-08-28.

^ Canadian Heraldic Authority (Volume II), Ottawa, 1994, p. 370

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Scholarly studies

- Bercuson, David J., J. L. Granatstein and W. R. Young. Sacred Trust?: Brian Mulroney and the Conservative Party in Power (1987)

- Blake, Raymond B. ed. Transforming the Nation: Canada and Brian Mulroney (McGill-Queen's University Press), 2007. 456pp; ISBN 978-0-7735-3214-4

- Clarkson, Stephen. Canada and the Reagan Challenge: Crisis and Adjustment, 1981–85 (2nd ed. 1985) excerpt and text search

- Donaldson, Gordon. The Prime Ministers of Canada (Toronto: Doubleday Canada Limited, 1997)

Popular books

Winners, Losers, by Patrick Brown (journalist), Rae Murphy, and Robert Chodos, 1976.

Where I Stand, by Brian Mulroney, McClelland and Stewart, Toronto, 1983, ISBN 0-7710-6671-6

Discipline of Power: the Conservative Interlude and the Liberal Restoration, by Jeffrey Simpson, Macmillan of Canada, 1984, ISBN 0-920510-24-8.

Brian Mulroney: The Boy from Baie Comeau, by Nick Auf der Maur, Rae Murphy, and Robert Chodos, 1984.

Mulroney: The Making of the Prime Minister, by L. Ian MacDonald, 1984.

The Insiders: Government, Business, and the Lobbyists, by John Sawatsky, 1987.

Prime Ministers of Canada, by Jim Lotz, 1987.

Selling Out: Four Years of the Mulroney Government, by Eric Hamovitch, Rae Murphy, and Robert Chodos, 1988.

Spoils of Power: the Politics of Patronage, by Jeffrey Simpson, 1988.

Friends in high places: politics and patronage in the Mulroney government, by Claire Hoy, 1989.

Betrayal of Canada, by Mel Hurtig, Stoddart Pub. Co., 1991, ISBN 0-7737-2542-3

Mulroney: The Politics of Ambition, by John Sawatsky, 1991.

Right Honourable Men: the Descent of Canadian Politics from Macdonald to Mulroney, by Michael Bliss, 1994.

On the Take: Crime, Corruption and Greed in the Mulroney Years, by Stevie Cameron, 1994.

The Prime Ministers of Canada, by Gordon Donaldson (journalist), 1997.

Promises, Promises: Breaking Faith in Canadian Politics, by Anthony Hyde, 1997.

Presumed Guilty: Brian Mulroney, the Airbus Affair, and the Government of Canada, by William Kaplan, 1998.

Prime Ministers: Rating Canada's Leaders, by Norman Hillmer and J.L. Granatstein, 1999. ISBN 0-00-200027-X.

The Last Amigo: Karlheinz Schreiber and the Anatomy of a Scandal, by Stevie Cameron and Harvey Cashore, 2001.

Egotists and Autocrats: The Prime Ministers of Canada, by George Bowering, 1999.

Bastards and Boneheads: Canada's Glorious Leaders, Past and Present, by Will Ferguson, 1999.

A Secret Trial: Brian Mulroney, Stevie Cameron, and the Public Trust, by William Kaplan, 2004.

The Secret Mulroney Tapes: Unguarded Confessions of a Prime Minister, by Peter C. Newman, 2005.

Master of Persuasion: Brian Mulroney's Global Legacy, by Fen Osler Hampson, 2018.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Brian Mulroney |

- Brian Mulroney – Parliament of Canada biography

- Ubben Lecture at DePauw University

- CBC Digital Archives – Brian Mulroney: The Negotiator

- "Brian Mulroney," by Norman Hillmer

Appearances on C-SPAN