Art Nouveau

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Paris metro station Abbesses, by Hector Guimard (1900); Lithograph by Alphonse Mucha (1897); Lamp by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1900–1910); Wall cabinet by Louis Majorelle; Interior of Hôtel Tassel by Victor Horta (1894) | |

| Years active | 1890–1910 |

|---|---|

| Country | International |

Art Nouveau (/ˌɑːrt nuːˈvoʊ, ˌɑːr/; French: [aʁ nuvo]) is an international style of art, architecture and applied art, especially the decorative arts, that was most popular between 1890 and 1910.[1] A reaction to the academic art of the 19th century, it was inspired by natural forms and structures, particularly the curved lines of plants and flowers.

English uses the French name Art Nouveau (new art). The style is related to, but not identical with, styles that emerged in many countries in Europe at about the same time: in Austria it is known as Secessionsstil after Wiener Secession; in Spanish Modernismo; in Catalan Modernisme; in Czech Secese; in Danish Skønvirke or Jugendstil; in German Jugendstil, Art Nouveau or Reformstil; in Hungarian Szecesszió; in Italian Art Nouveau, Stile Liberty or Stile floreale; in Latvian Jūgendstils; in Lithuanian Modernas; in Norwegian Jugendstil; in Polish Secesja; in Slovak Secesia; in Ukrainian and Russian Модерн (Modern); in Swedish and Finnish Jugend.

Art Nouveau is a total art style: It embraces a wide range of fine and decorative arts, including architecture, painting, graphic art, interior design, jewelry, furniture, textiles, ceramics, glass art, and metal work.

By 1910, Art Nouveau was already out of style. It was replaced as the dominant European architectural and decorative style first by Art Deco and then by Modernism.[2][3]

Contents

1 Naming

2 History

2.1 Origins

2.2 Maison de l'Art Nouveau (1895)

2.3 Beginning of Art Nouveau architecture (1893–1898)

2.4 Paris Exposition universelle (1900)

2.5 Art Nouveau in France

2.6 Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland

2.7 Modern Style and Glasgow School in Britain

2.8 Jugendstil in Germany

2.9 Vienna Secession in Austria

2.10 Secession in Central Europe

2.11 Stile Liberty in Italy

2.12 Modernisme in Spain, Arte Nova in Portugal

2.13 Jugendstil in the Nordic Countries

2.14 World of Art in Russia

2.15 Tiffany Style in the United States

3 Form and character

4 Relationship with contemporary styles and movements

5 Graphics

6 Painting

7 Glass art

8 Metal art

9 Jewelry

10 Architecture

11 Furniture

12 Ceramics

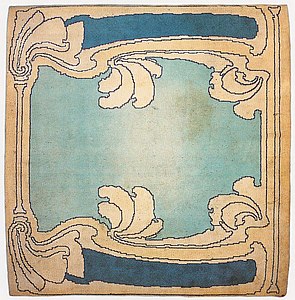

13 Textiles and wallpaper

14 See also

15 References

16 Bibliography

17 Further reading

18 External links

Naming

Art Nouveau took its name from the Maison de l'Art Nouveau (House of the New Art), an art gallery opened in 1895 by the Franco-German art dealer Siegfried Bing that featured the new style. In France, Art Nouveau was also sometimes called by the British term "Modern Style" due to its roots in the Arts and Crafts movement, Style moderne, or Style 1900.[4] It was also sometimes called Style Jules Verne, Le Style Métro (after Hector Guimard's iron and glass subway entrances), Art Belle Époque, and Art fin de siècle.[5]

In Belgium, where the architectural movement began, it was sometimes termed Style nouille (noodle style) or Style coup de fouet (whiplash style).[5]

In Britain, it was known as the Modern Style, or, because of the Arts and Crafts movement led by Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow, as the "Glasgow" style.

In Italy, because of the popularity of designs from London's Liberty & Co department store (mostly designed by Archibald Knox), it was often called Stile Liberty ("Liberty style"), Stile floreale, or Arte nuova (New Art).

In the United States, due to its association with Louis Comfort Tiffany, it was often called the "Tiffany style".[3][3][4][4]

In Germany and Scandinavia, a related style emerged at about the same time; it was called Jugendstil, after the popular German art magazine of that name.[5] In Austria and the neighboring countries then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a similar style emerged, called Secessionsstil in German, (Hungarian: szecesszió, Czech: secese) or Wiener Jugendstil, after the artists of the Vienna Secession.

The style was called Modern (Модерн) in Russia and Nieuwe Kunst (new art) in the Netherlands.[3][4] In Spain the related style was known as Modernismo, Modernisme (in Catalan), Arte joven ("young art"); and in Portugal Arte nova (new art).

Some names refer specifically to the organic forms that were popular with the Art Nouveau artists: Stile Floreal ("floral style") in France; Paling Stijl ("eel style") in the Netherlands; and Wellenstil ("wave style") and Lilienstil ("lily style") in Germany.[4]

History

Origins

The Red House by William Morris and Philip Webb (1859)

Japanese woodblock print by Utagawa Kunisada (1850s)

The Peacock Room by James McNeil Whistler (1876–1877)

William Morris printed textile design (1883)

Swan, rush and iris wallpaper design by Walter Crane (1883)

The new art movement had its roots in Britain, in the floral designs of William Morris, and in the Arts and Crafts movement founded by the pupils of Morris. Early prototypes of the style include the Red House of Morris (1859), and the lavish Peacock Room by James Abbott McNeill Whistler. The new movement was also strongly influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite painters, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, and especially by British graphic artists of the 1880s, including Selwyn Image, Heywood Sumner, Walter Crane, Alfred Gilbert, and especially Aubrey Beardsley.[6]

In France, the style combined several different tendencies. In architecture, it was influenced by the architectural theorist and historian Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, a declared enemy of the historical Beaux-Arts architectural style. In his 1872 book Entretiens sur l'architecture, he wrote, "use the means and knowledge given to us by our times, without the intervening traditions which are no longer viable today, and in that way we can inaugurate a new architecture. For each function its material; for each material its form and its ornament."[7] This book influenced a generation of architects, including Louis Sullivan, Victor Horta, Hector Guimard, and Antoni Gaudí.[8]

The French painters Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard played an important part in integrating fine arts painting with decoration. "I believe that before everything a painting must decorate", Denis wrote in 1891. "The choice of subjects or scenes is nothing. It is by the value of tones, the colored surface and the harmony of lines that I can reach the spirit and wake up the emotions."[9] These painters all did both traditional painting and decorative painting on screens, in glass, and in other media.[10]

Another important influence on the new style was Japonism: the wave of enthusiasm for Japanese woodblock printing, particularly the works of Hiroshige, Hokusai, and Utagawa Kunisada which were imported into Europe beginning in the 1870s. The enterprising Siegfried Bing founded a monthly journal, Le Japon artistique in 1888, and published thirty-six issues before it ended in 1891. It influenced both collectors and artists, including Gustav Klimt. The stylized features of Japanese prints appeared in Art Nouveau graphics, porcelain, jewelry, and furniture.

New technologies in printing and publishing allowed Art Nouveau to quickly reach a global audience. Art magazines, illustrated with photographs and color lithographs, played an essential role in popularizing the new style. The Studio in England, Arts et idèes and Art et décoration in France, and Jugend in Germany allowed the style to spread rapidly to all corners of Europe. Aubrey Beardsley in England, and Eugène Grasset, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Félix Vallotton achieved international recognition as illustrators.[11]

With the posters by Jules Cheret for dancer Loie Fuller in 1893, and by Alphonse Mucha for actress Sarah Bernhardt in 1895, the poster became not just advertising, but an art form.

Maison de l'Art Nouveau (1895)

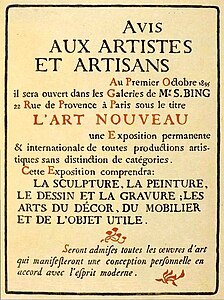

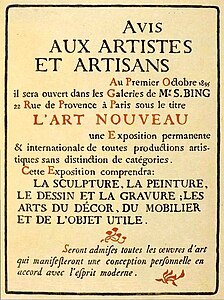

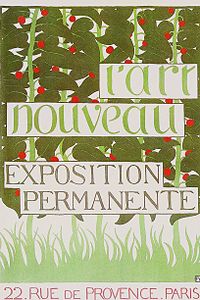

Siegfried Bing invited artists to show modern works in his new Maison de l'Art Nouveau (1895).

The Maison de l'Art Nouveau gallery of Siegfried Bing (1895)

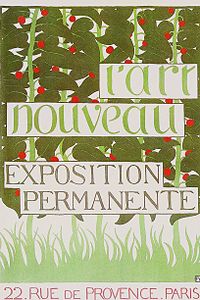

Poster by Félix Vallotton for the new Maison de l'Art Nouveau (1896)

The Franco-German art dealer and publisher Siegfried Bing played a key role in publicizing the style. In 1891, he founded a magazine devoted to the art of Japan, which helped publicize Japonism in Europe. In 1892, he organized an exhibit of seven artists, among them Pierre Bonnard, Félix Vallotton, Édouard Vuillard, Toulouse-Lautrec and Eugène Grasset, which included both modern painting and decorative work. This exhibition was shown at the Société nationale des beaux-arts in 1895. In the same year, Bing opened a new gallery at 22 rue de Provence in Paris, the Maison de l'Art Nouveau, devoted to new works in both the fine and decorative arts. The interior and furniture of the gallery were designed by the Belgian architect Henry Van de Velde, one of the pioneers of Art Nouveau architecture. The Maison de l'Art Nouveau showed paintings by Georges Seurat, Paul Signac and Toulouse-Lautrec, glass from Louis Comfort Tiffany and Emile Gallé, jewelry by René Lalique, and posters by Aubrey Beardsley. The works shown there were not at all uniform in style. Bing wrote in 1902, "Art Nouveau, at the time of its creation, did not aspire in any way to have the honor of becoming a generic term. It was simply the name of a house opened as a rallying point for all the young and ardent artists impatient to show the modernity of their tendencies."[12]

Beginning of Art Nouveau architecture (1893–1898)

Bloemenwerf house in Brussels, by Henry Van de Velde (1895)

Bloemenwerf chair made by Henry Van de Velde for his residence (1895)

Gateway of the Castel Béranger by Hector Guimard (1895–1898)

The first Art Nouveau houses, the Hôtel Tassel by Victor Horta and the Bloemenwerf house by Henry Van de Velde, were built in Brussels in 1893–1895. Both Horta and Van de Velde designed not only the houses, but also all of the interior decoration, furniture, carpets, and architectural details.

Horta, an architect with classical training, designed the residence of a prominent Belgian chemist, Émile Tassel, on a very narrow and deep site. The central element became the stairway, beneath a high skylight. The floors were supported by slender iron columns like the trunks of trees. The mosaic floors and walls were decorated with delicate arabesques in floral and vegetal forms, which became the most popular signature of Art Nouveau.[13]

Van de Velde was by training a designer, not an architect, and collaborated with an architect on the plan of the Bloemenwerf, the house that he built for himself. He was inspired by the British Arts and Crafts Movement, particularly William Morris's Red House, and like them he designed all aspects of the building, including the furniture, wallpaper and carpets.

After visiting Horta's Hôtel Tassel, Hector Guimard built the Castel Béranger, the first Paris building in the new style, between 1895 and 1898. Parisians had been complaining of the monotony of the architecture of the boulevards built under Napoleon III by Georges-Eugène Haussmann. They welcomed Guimard's colorful and picturesque style; the Castel Béranger was chosen as one of the best new façades in Paris, launching Guimard's career. Guimard was given the commission to design the entrances for the new Paris Métro system, which brought the style to the attention of the millions of visitors to the city's 1900 Exposition Universelle.[5]

Paris Exposition universelle (1900)

Main entrance to the Paris 1900 Exposition universelle

The Bigot Pavilion, showcasing the work of ceramics artist Alexandre Bigot

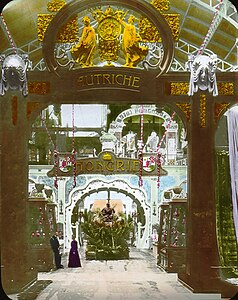

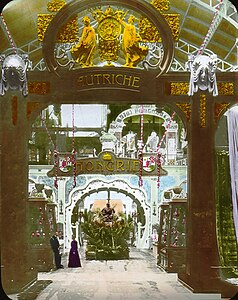

Entrance to the Austrian exhibit

The German Pavilion by Bruno Möhring

Paris metro station entrance at Abbesses designed by Hector Guimard for the 1900 Exposition universelle

The Paris 1900 Exposition universelle marked the high point of Art Nouveau. Between April and November 1900, it attracted nearly fifty million visitors from around the world, and showcased the architecture, design, glassware, furniture and decorative objects of the style. The architecture of the Exposition was often a mixture of Art Nouveau and Beaux-Arts architecture: the main exhibit hall, the Grand Palais had a Beaux-Arts façade completely unrelated to the spectacular Art Nouveau stairway and exhibit hall in the interior.

The Exposition particularly highlighted French designers, who all made special works for the Exhibition: Lalique crystal and jewelry; jewelry by Henri Vever and Georges Fouquet; Daum glass; the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres in porcelain; ceramics by Alexandre Bigot; sculpted glass lamps and vases by Emile Gallé and Louis Comfort Tiffany, and Company from the United States; furniture by Édouard Colonna and Louis Majorelle; and many other prominent arts and crafts firms from around Europe and the world. At the 1900 Paris Exposition, Siegfried Bing presented a pavilion called Art Nouveau Bing, which featured six different interiors entirely decorated in the Style.[14][15]

While the Paris Exposition was by far the largest, other expositions did much to popularize the style. The 1888 Barcelona Universal Exposition marked the beginning of the Modernisme style in Spain, with some buildings of Lluís Domènech i Montaner. The Esposizione internazionale d'arte decorativa moderna of 1902 in Turin, Italy, showcased designers from across Europe.

Art Nouveau in France

Le Train bleu at the Gare de Lyon (1900)

Doorway of the Lavirotte Building by Jules Lavirotte, 29 avenue Rapp, Paris (1901)

Cupola of the headquarters of Société générale at 29 boulevard Haussmann, by Jacques Hermant (1905–11)

The glass cupola of the department store Galeries Lafayette (1912)

The Villa Majorelle in Nancy by Henri Sauvage (1901–02)

The jewellery shop of Georges Fouquet at 6 rue Royale, Paris, designed by Alphonse Mucha, now in the Carnavalet Museum (1901)

Following the 1900 Exposition, the capital of Art Nouveau was Paris. The most extravagant residences in the style were built by Jules Lavirotte, who entirely covered the façades with ceramic sculptural decoration. The most flamboyant example is the Lavirotte Building, at 29 avenue Rapp (1901). Office buildings and department stores featured high courtyards covered with stained glass cupolas and ceramic decoration. The style was particularly popular in restaurants and cafés, including Maxim's at 3 rue Royale, and Le Train bleu at the Gare de Lyon (1900).[16]

The city of Nancy in Lorraine became the other French capital of the new style. In 1901, the Alliance provinciale des industries d'art, also known as the École de Nancy, was founded, dedicated to upsetting the hierarchy that put painting and sculpture above the decorative arts. The major artists working there included the glass vase and lamp creators Emile Gallé, the Daum brothers in glass design, and the designer Louis Majorelle, who created furniture with graceful floral and vegetal forms. The architect Henri Sauvage brought the new architectural style to Nancy with his Villa Majorelle in 1898.

The French style was widely propagated by new magazines, including The Studio, Arts et Idées and Art et Décoration, whose photographs and color lithographs made the style known to designers and wealthy clients around the world.

In France, the style reached its summit in 1900, and thereafter slipped rapidly out of fashion, virtually disappearing from France by 1905. Art Nouveau was a luxury style, which required expert and highly-paid craftsmen, and could not be easily or cheaply mass-produced. One of the few Art Nouveau products that could be mass-produced was the perfume bottle, and these continue to be manufactured in the style today.

Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland

House of architect Paul Hankar in Brussels (1893)

Chair by Henry Van de Velde (1896)

Poster by Theophile-Alexandre Steinlen for the cabaret Le Chat noir (1896)

Bed and mirror by Gustave Serrurier-Bovy (1898–99), now in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Philippe Wolfers, Plume de Paon, (Collection King Baudouin Foundation, depot: KMKG-MRAH)

Philippe Wolfers, Civilisation et Barbarie, Collection King Baudouin Foundation, depot: KMKG-MRAH

Belgium was an early center of the Art Nouveau, thanks largely to the architecture of Victor Horta, who designed the first Art Nouveau houses, the Hôtel Tassel in 1893, and the Hôtel Solvay in 1894. Horta met and had a strong influence on the work of the young Hector Guimard. Other important designers included architect Paul Hankar, who built an Art Nouveau house in 1893; the architect and furniture designer Henry van de Velde, the decorator Gustave Serrurier-Bovy, and the graphic artist Fernand Khnopff.[17][18][19] Belgian designers took advantage of an abundant supply of ivory imported from the Belgian Congo; mixed sculptures, combining stone, metal and ivory, by such artists as Philippe Wolfers, was popular.[20]

In the Netherlands, the style was known as the Nieuwe Kunst, the New Art. Architects included Hendrik Petrus Berlage, who designed a more functional, rational variant, while Carel Adolph Lion Cachet, Theo Nieuwenhuis and Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof designed a more picturesque and decorative style. Furniture design was influenced by the importation of exotic woods from the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia), while textiles were influenced by the designs and techniques of batik.[20]

Prominent Swiss artists of the period included painter and graphic artist Théophile Steinlen, creator of the famous poster for the Paris cabaret Le Chat noir, and the artist, sculptor and decorator Eugène Grasset, who moved from Switzerland to Paris where he designed graphics, furniture, tapestries, ceramics and posters. In Paris, he taught at the Guérin school of art (École normale d'enseignement du dessin), where his students included Augusto Giacometti and Paul Berthon.[21][22]

Modern Style and Glasgow School in Britain

Cover design by Arthur Mackmurdo for a book on Christopher Wren (1883)

Willow Tearooms by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, in Kelvingrove, Glasgow (1893)

Belt buckle by Archibald Knox for Liberty Department Store

Embroidered panels by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1902)

Art Nouveau had its roots in Britain, in the arts and crafts movement of the 1880s, which called for a closer union between the fine arts and decorative arts, and a break away from historical styles to designs inspired by function and nature. One notable early example Arthur Mackmurdo's design for the cover of his essay on the city churches of Sir Christopher Wren, published in 1883.

Other important innovators in Britain included the graphic designers Aubrey Beardsley whose drawings featured the curved lines which became the most recognizable feature of the style. free-flowing wrought iron from the 1880s could also be adduced, or some flat floral textile designs, most of which owed some impetus to patterns of 19th century design. Other British graphic artists who had an important place in the style included Walter Crane and Charles Ashbee.[23]

The Liberty department store in London played an important role, through its colorful stylized floral designs for textiles, and the silver, pewter, and jewelry designs of Manxman (of Scottish descent) Archibald Knox. His jewelry designs in materials and forms broke away entirely from the historical traditions of jewelry design.

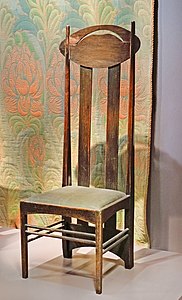

For Art Nouveau architecture and furniture design, the most important center in Britain was Glasgow, with the creations of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow School, whose work was inspired by the French Art Nouveau, Japanese art, symbolism and Gothic revival. Beginning in 1895, Mackintosh displayed his designs at international expositions in London, Vienna, and Turin; his designs particularly influenced the Secession Style in Vienna. His architectural creations included the Glasgow Herald Building (1894) and the library of the Glasgow School of Art (1897). He also established a major reputation as a furniture designer and decorator, working closely with his wife, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, a prominent painter and designer. Together they created striking designs which combined geometric straight lines with gently curving floral decoration, particularly a famous symbol of the style, the Glasgow Rose".[24]

Léon-Victor Solon, made an important contribution to Art Nouveau ceramics as art director at Mintons. He specialised in plaques and in tube-lined vases marketed as "secessionist ware" (usually described as named after the Viennese art movement).[25] Apart from ceramics, he designed textiles for the Leek silk industry[26] and doublures for a bookbinder (G.T.Bagguley of Newcastle under Lyme), who patented the Sutherland binding in 1895.

The Edward Everard building in Bristol, built during 1900–01 to house the printing works of Edward Everard, features an Art Nouveau façade. The figures depicted are of Johannes Gutenberg and William Morris, both eminent in the field of printing. A winged figure symbolises the "Spirit of Light", while a figure holding a lamp and mirror symbolises light and truth.

Jugendstil in Germany

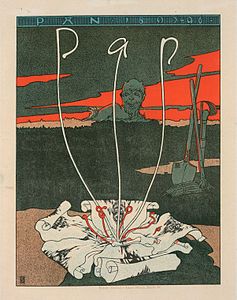

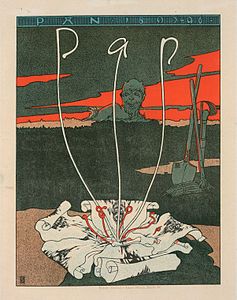

Cover of Pan magazine by Joseph Sattler (1895)

Cover of Jugend by Otto Eckmann (1896)

Tapestry The Five Swans by Otto Eckmann (1896–97)

Jugendstil door handle in Berlin (circa 1900)

Chair by Richard Riemerschmid (1902)

Stoneware jug by Richard Riemerschmid (1902)

German Art Nouveau is commonly known by its German name, Jugendstil. The name is taken from the artistic journal, Die Jugend, which was published in Munich and which espoused the new artistic movement. It was founded in 1896 by Georg Hirth (Hirth remained editor until his death in 1916, and the magazine continued to be published until 1940). The magazine was instrumental in promoting the style in Germany. As a result, its name was adopted as the most common German-language term for the style: Jugendstil ("youth style"). Although, during the early 20th century, the word was applied to only two-dimensional examples of the graphic arts,[27] especially the forms of organic typography and graphic design found in and influenced by German magazines like Jugend, Pan, and Simplicissimus, it is now applied to more general manifestations of Art Nouveau visual arts in Germany, the Netherlands, the Baltic states, and Nordic countries.[3][28] The two main centres for Jugendstil art in Germany were Munich and Darmstadt (Mathildenhöhe).

Two other journals, Simplicissimus, published in Munich, and Pan, published in Berlin, proved to be important proponents of the Jugendstil. The magazines were important for spreading the visual idiom of Jugendstil, especially the graphical qualities. Jugendstil art includes a variety of different methods, applied by the various individual artists and features the use of hard lines as well as sinuous curves. Methods range from classic to romantic. One feature of Jugendstil is the typography used, the letter and image combination of which is unmistakable. The combination was used for covers of novels, advertisements, and exhibition posters. Designers often used unique display typefaces that worked harmoniously with the image.

One of the most famous German artists associated with both Die Jugend and Pan was Otto Eckmann. His favourite animal was the swan, and such was his influence in the German movement that the swan came to serve as the leitmotif for the Jugendstil.

One of the most prominent German designers in the style was Richard Riemerschmid, who made furniture, pottery, and other decorative objects in a sober, geometric style that pointed forward toward Art Deco.[29]

Vienna Secession in Austria

The Secession Hall in Vienna by Joseph Maria Olbrich (1897)

Karlsplatz Stadtbahn Station by Otto Wagner (1899)

Poster by Koloman Moser (1899)

The Palais Stoclet in Brussels by Josef Hoffmann (1905–1911)

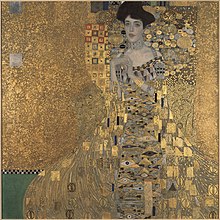

The Kiss by Gustav Klimt (1907–08)

Vienna became the center of a distinct variant of Art Nouveau, which became known as the Vienna Secession, an art movement that was founded in April 1897 by a group of artists which included Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Max Kurzweil, and Otto Wagner. The painter Klimt became the president of the group. They objected to the conservative orientation toward historicism expressed by Vienna Künstlerhaus, the official union of artists. The Secession founded a magazine, Ver Sacrum, to promote their works in all media. The Secession style was notably more feminine, less heavy and less nationalist than the Jugendstil in neighboring Germany.[30] The architect Joseph Olbrich designed the domed Secession building in the new style, which became a showcase for the paintings of Gustav Klimt and other Secession artists. The architectural style of the Vienna Secession had an influence well beyond the city. Buildings in the style appeared in the other major cities of the Empire and beyond; one of the most famous examples is the Stoclet Palace built by Josef Hoffmann in Brussels in 1905–11. The interior is entirely decorated in Secession style, including notable paintings by Gustav Klimt.

Klimt became the best-known of the Secession painters, often erasing the border between fine art painting and decorative painting. Koloman Moser was an extremely versatile artist in the style; his work including magazine illustrations, architecture, silverware, ceramics, porcelain, textiles, stained glass windows, furniture, and more. He often worked in collaboration with Hoffmann and Klimt; the three together created the interiors, furnishing and even clothing to be worn in the Stoclet Palace in Brussels. In 1903, he and Hoffmann founded the Wiener Werkstätte, a training school and workshop for designers and craftsmen of furniture, carpets, textiles and decorative objects.[31]

Secession in Central Europe

Reök Palace in Szeged downtown on the Magyar Ede square, named after its architect.

Cabinet by Ödön Faragó, from Budapest (1901)

Hotel Meran in Prague

The Jubilee Synagogue in Prague (1908)

Culture house in Skalica (Slovakia)

In the capitals of Central Europe, then ruled by the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Vienna, national forms of Art Nouveau are quick to appear, and often took on historical or folkloric elements. The furniture designs of Ödön Faragó in Budapest (Hungary) combined traditional popular architecture, oriental architecture and international Art Nouveau in a highly picturesque style. Pál Horti, another Hungarian designer, had a much more sober and functional style, made of oak with delicate traceries of ebony and brass.

Prague, in the Czech Republic, has a notable collection of Art Nouveau architecture, including the Hotel Central and the Jubilee Synagogue, built in 1908.

The style of combining Art Nouveau and national architectural elements was typical also for a Slovak architect Dušan Jurkovič who was under the influence of Hungarian Art Nouveau. His most original works are the Cultural House in Skalica in Slovakia (1905), buildings of spa in Luhačovice in the Czech Republic (1901–1903) and 35 war cemeteries near Nowy Żmigród in Galicia (now Poland), most of them heavily influenced by local Lemko (Rusyn) folk art and carpentry (1915–1917). Another example of Secession architecture in Slovakia is the Church of St. Elisabeth (The Little Blue Church) in Bratislava.

Stile Liberty in Italy

The Teatro Massimo in Palermo (1897)

Floral vase by Galileo Chini (1896–98)

Casa Fenoglio-La Fleur in Turin, designed by Pietro Fenoglio (1907)

Carlo Bugatti, Cobra Chair and Desk. 1902. Brooklyn Museum

Tea and coffee service with salver and stand, by Carlo Bugatti (1907)

Primavera panel by Galileo Chini (1914)

Italy's Stile Liberty took its name from the British department store Liberty, the colorful textiles of which were particularly popular in Italy. Notable Italian designers included Galileo Chini, whose ceramics were inspired both by majolica patterns and by Art Nouveau. He was later known as a painter and a scenic designer; he designed the sets for two Puccini operas Gianni Schicchi and Turandot.

The Teatro Massimo in Palermo, by the architect Ernesto Basile, is an example of the Italian variant of the style, architectural style, which combined Art Nouveau and classical elements.

The most important figure in Italian Art Nouveau furniture design was Carlo Bugatti, the son of an architect and sculptor, and brother of the famous automobile designer. He studied at the Milanese Academy of Brera, and later the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His work was distinguished by its exoticism and eccentricity, included silverware, textiles, ceramics, and musical instruments, but he is best remembered for his innovative furniture designs, shown first in the 1888 Milan Fine Arts Fair. His furniture often featured a keyhole design, and had unusual coverings, including parchment and silk, and inlays of bone and ivory. It also sometimes had surprising organic shapes, copied after snails and cobras.[32]

Modernisme in Spain, Arte Nova in Portugal

Sagrada Família basilica in Barcelona by Antoni Gaudí (1883–)

The Casa Batlló, remodeled by Antoni Gaudí and Josep Maria Jujol (1904–1906)

Casa Milà by Antoni Gaudí (1906–1908)

Ceiling of the Palau de la Música Catalana, by Lluis Domenech i Montaner (1905–08)

Buffet from casa Lleo Morera by the Catalan designer Gaspar Homar (1904)

The Livraria Lello bookstore in Porto, Portugal (1906)

In Spain, a highly original variant of the style, Catalan Modernisme, appeared in Barcelona. Its most famous creator was Antoni Gaudí, who used Art Nouveau's floral and organic forms in a very novel way in Palau Güell (1886).[33][34] His designs from about 1903, the Casa Batlló (1904–1906) and Casa Milà (1906–1908), are most closely related to the stylistic elements of Art Nouveau.[35] However, famous structures such as the Sagrada Família characteristically contrast the modernising Art Nouveau tendencies with revivalist Neo-Gothic.[35] Besides the dominating presence of Gaudí, Lluís Domènech i Montaner also used Art Nouveau in Barcelona in buildings such as the Castell dels Tres Dragons (1888), Palau de la Música Catalana and Casa Lleó Morera (1905).[35] Another major modernista was Josep Puig i Cadafalch, who designed the Casa Martí and its Quatre Gats café, the Casimir Casaramona textile factory (now the CaixaFòrum art museum), Casa Macaya, Casa Amatller, the Palau del Baró de Quadras (housing Casa Àsia for 10 years until 2013) and the Casa de les Punxes ("House of Spikes"). Also well-known is Josep Maria Jujol, with houses in Sant Joan Despí (1913–1926), several churches near Tarragona (1918 and 1926) and the sinuous Casa Planells (1924) in Barcelona. A few other major architects working outside of Barcelona were Lluís Muncunill i Parellada, with a magnificent textile factory in Terrassa (Vapor Aymerich, Amat i Jover, now the Science and Technology Museum of Catalonia – Museu de la Ciència i de la Tècnica de Catalunya) and a "farmhouse"/small manor house called Masia Freixa in the same city; and Cèsar Martinell i Brunet, with his spectacular "wine cathedrals", housing town cooperative wineries throughout southern and central Catalonia. A Valencian architect who worked in Catalonia before emigrating to the States was Rafael Guastavino. Attributed to him is the Asland Cement Factory in Castellar de n'Hug, among other buildings.

The Catalan furniture designer Gaspar Homar (1870–1953), influenced by Antoni Gaudí, often combining marquetry and mosaics with his furnishings.[36] Examples of Art Nouveau (Arte nova), based largely on the French model, appeared in Portugal in Porto and Aveiro. A notable example is the 'Livraria Lello' bookstore in Porto, designed by Xavier Esteves (1906).

Jugendstil in the Nordic Countries

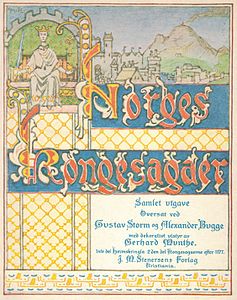

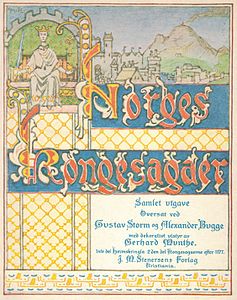

VIking dragon-head chair and tapestry by Gerhard Munthe of Norway (1898)

Graphic design by Gerhard Munthe (1914)

Viking-Art Nouveau Chair by Norwegian designer Lars Kinsarvik (1900)

Interior of Tampere Cathedral in Finland by Lars Sonck (1902–1907)

Chair by Eliel Saarinen (1907–1908)

Helsinki railway station by Eliel Saarinen (1909–1919)

Art Nouveau was popular in the Nordic countries, where it was usually known as Jugendstil, and was often combined with the National Romantic Style of each country. In Norway the Art Nouveau was connected with a revival inspired by Viking folk art and crafts. Notable designers included Lars Kisarvik, who designed chairs with traditional Viking and Celtic patterns, and Gerhard Munthe, who designed a chair with a stylized dragon-head emblem from ancient Viking ships, as well as a wide variety of posters, paintings and graphics.[37] Other examples include the Skien Church (1887–1894) and Fagerborg Church in Kristiania (Oslo) (1900–1903).

In Finland, good examples are the Helsinki Central railway station, designed by Eliel Saarinen, father of the famous American modernist architect Eero Saarinen. Examples of the style include the Finnish National Theatre, Kallio Church, the Finnish National Museum, and Tampere Cathedral. In contrast to the very elaborate furniture of the Norwegian Art Nouveau, Finnish Art Deco was extremely simple and functional, as in the chairs designed by Eliel Saarinen (1907-1908).[38][39]

World of Art in Russia

An Art Nouveau Fabergé egg made as an Easter gift from Czar Nicholas II of Russia to his wife (1898))

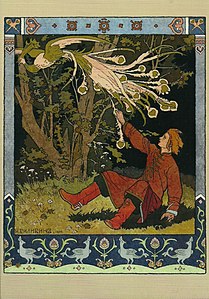

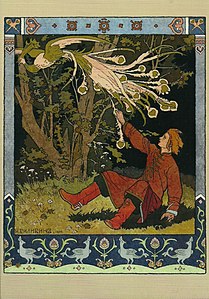

Illustration of the Firebird by Ivan Bilibin (1899)

Set for Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's ballet Scheherazade by Leon Bakst (1910)

Program design for "Afternoon of a Faun" by Leon Bakst for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, (1912)

The interior of the Vitebsk Railway Station in Saint Petersburg (1904)

Façade of the Hotel Metropol in Moscow, with mosaic by Mikhail Vrubel (1899–1907)

A very colorful Russian variation of Art Nouveau appeared in Moscow and Saint Petersburg in 1898 with the publication of a new art journal, "Мир искусства" (transliteration: Mir Iskusstva) ("The World of Art"), by Russian artists Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst, and chief editor Sergei Diaghilev. The magazine organized exhibitions of leading Russian artists, including Mikhail Vrubel, Konstantin Somov, Isaac Levitan, and the book illustrator Ivan Bilibin. The World of Art style made less use of the vegetal and floral forms of French Art Nouveau; it drew heavily upon the bright colors and exotic designs of Russian folklore and fairy tales. The most influential contribution of the "World of Art" was the creation by Diaghilev of a new ballet company, the Ballets Russes, headed by Diaghilev, with costumes and sets designed by Bakst and Benois. The new ballet company premiered in Paris in 1909, and performed there every year through 1913. The exotic and colorful sets designed by Benois and Bakst had a major impact on French art and design. The costume and set designs were reproduced in the leading Paris magazines, L'Illustration, La Vie parisienne and Gazette du bon ton, and the Russian style became known in Paris as à la Bakst. The company was stranded in Paris first by the outbreak of World War I, and then by the Russian Revolution in 1917, and ironically never performed in Russia.[40]

Moscow and Saint Petersburg have several prominent Art Nouveau buildings constructed in the last years before the Revolution; notably the Hotel Metropol in Moscow, which features a ceramic mural on the façade, The Princess of Dreams, by scenic designer Mikhail Vrubel; and the Vitebsk Railway Station in Saint Petersburg (1904)

Tiffany Style in the United States

Transportation Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago by Louis Sullivan

Tiffany Chapel from the 1893 Word's Columbian Exposition, now in the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida.

Glass vase by Louis Comfort Tiffany now in the Cincinnati Art Museum (1893–96)

Lily lamp by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1900–1910)

Tiffany window in his house at Oyster Bay, New York

The Flight of Souls Window by Louis Comfort Tiffany won a gold medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition

In the United States, the firm of Louis Comfort Tiffany played a central role in American Art Nouveau. Born in 1848, he studied at the National Academy of Design in New York, began working with glass at the age of 24, entered the family business started by his father, and 1885 set up his own enterprise devoted to fine glass, and developed new techniques for its coloring. In 1893, he began making glass vases and bowls, again developing new techniques that allowed more original shapes and coloring, and began experimenting with decorative window glass. Layers of glass were printed, marbled and superimposed, giving an exceptional richness and variety of color In 1895 his new works were featured in the Art Nouveau gallery of Siegfried Bing, giving him a new European clientele. After the death of his father in 1902, he took over the entire Tiffany enterprise, but still devoted much of his time to designing and manufacturing glass art objects. At the urging of Thomas Edison, he began to manufacture electric lamps with multicolored glass shades in structures of bronze and iron, or decorated with mosaics, produced in numerous series and editions, each made with the care of a piece of jewelry. A team of designers and craftsmen worked on each product. The Tiffany lamp in particular became one of the icons of the Art Nouveau, but Tiffany's craftsmen (and craftswomen) designed and made extraordinary windows, vases, and other glass art. Tiffany's glass also had great success at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris; his stained glass window called the Flight of Souls won a gold medal.[41]

Another important figure in American Art Nouveau was the architect Louis Sullivan, best known as the architect of some of the first American iron-framed skyscrapers. At the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, most famous for the neoclassical architecture of its renowned White City, he designed a spectacular Art Nouveau entrance to the Transportation Building. The Columbian Exposition was also an important venue for Tiffany; a chapel he designed was shown at the Pavilion of Art and Industry. The Tiffany Chapel, along with one of the windows of Tiffany's home in New York, are now on display at the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida.

Form and character

La tournée du Chat noir de Rodolphe Salis (1896) by Théophile Steinlen

Although Art Nouveau acquired distinctly localised tendencies as its geographic spread increased, some general characteristics are indicative of the form. A description published in Pan magazine of Hermann Obrist's wall hanging Cyclamen (1894) described it as "sudden violent curves generated by the crack of a whip", which became well known during the early spread of Art Nouveau.[42] Subsequently, not only did the work itself become better known as The Whiplash but the term "whiplash" is frequently applied to the characteristic curves employed by Art Nouveau artists.[42] Such decorative "whiplash" motifs, formed by dynamic, undulating, and flowing lines in a syncopated rhythm and asymmetrical shape, are found throughout the architecture, painting, sculpture, and other forms of Art Nouveau design.

The origins of Art Nouveau are sometimes attributed in the resistance of the artist William Morris to the cluttered compositions and the revival tendencies of the 19th century and his theories that helped initiate the Arts and crafts movement.[43]Arthur Mackmurdo's book-cover for Wren's City Churches (1883), with its rhythmic floral patterns, is also sometimes described as the first realisation of Art Nouveau.[43] About the same time, the flat perspective and strong colors of Japanese wood block prints, especially those of Katsushika Hokusai, had a strong effect on the formulation of Art Nouveau.[44] The Japonisme that was popular in Europe during the 1880s and 1890s was particularly influential on many artists with its organic forms and references to the natural world.[44] Besides being adopted by artists like Emile Gallé and James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Japanese-inspired art and design was championed by the businessmen Siegfried Bing and Arthur Lasenby Liberty at their stores[45] in Paris and London, respectively.[44]

Doorway at 24 place Etienne Pernet, (Paris 15e), 1905 Alfred Wagon, architect.

In architecture, hyperbolas and parabolas in windows, arches, and doors are common, and decorative mouldings 'grow' into plant-derived forms. Like most design styles, Art Nouveau sought to harmonise its forms. The text above the Paris Metro entrance uses the qualities of the rest of the iron work in the structure.[46]

Art Nouveau in architecture and interior design eschewed the eclectic revival styles of the 19th century. Though Art Nouveau, designers selected and 'modernised' some of the more abstract elements of Rococo style, such as flame and shell textures, they also advocated the use of very stylised organic forms as a source of inspiration, expanding the 'natural' repertoire to use seaweed, grasses, and insects. The softly-melding forms of 17th-century auricular style, best exemplified in Dutch silverware, was another influence.

Relationship with contemporary styles and movements

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I by Gustav Klimt (1907)

As an art style, Art Nouveau has affinities with the Pre-Raphaelites and the Symbolist styles, and artists like Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Edward Burne-Jones, Gustav Klimt and Jan Toorop could be classed in more than one of these styles. Unlike Symbolist painting, however, Art Nouveau has a distinctive appearance; and, unlike the artisan-oriented Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau artists readily used new materials, machined surfaces, and abstraction in the service of pure design.

Art Nouveau did not eschew the use of machines, as the Arts and Crafts Movement did. For sculpture, the principal materials employed were glass and wrought iron, resulting in sculptural qualities even in architecture. Ceramics were also employed in creating editions of sculptures by artists such as Auguste Rodin.[47]

Art Nouveau architecture made use of many technological innovations of the late 19th century, especially the use of exposed iron and large, irregularly shaped pieces of glass for architecture.

Art Nouveau tendencies were also absorbed into local styles. In Denmark, for example, it was one aspect of Skønvirke ("aesthetic work"), which itself more closely relates to the Arts and Crafts style.[48][49] Likewise, artists adopted many of the floral and organic motifs of Art Nouveau into the Młoda Polska ("Young Poland") style in Poland.[50]Młoda Polska, however, was also inclusive of other artistic styles and encompassed a broader approach to art, literature, and lifestyle.[51]

Graphics

The Peacock Skirt, by Aubrey Beardsley, (1892)

First issue of The Studio, with cover by Aubrey Beardsley (1893)

Poster for the dancer Loie Fuller by Jules Chéret (1893)

Poster for Grafton Galleries by Eugène Grasset (1893)

Divan Japonais lithograph by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1892–93)

The Inland Printer magazine cover by Will H. Bradley (1894)

Poster for The Chap-Book by Will H. Bradley (1895)

Biscuits Lefèvre-Utile by Alphonse Mucha (1896)

Zodiac Calendar by Alphonse Mucha (1896)

Motocycles Comiot by Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen from Les Maîtres de l'affiche (1899)

Ver Sacrum illustration by Koloman Moser (1899)

illustration from Ver Sacrum by Koloman Moser (1900)

Festival poster by Ludwig Hohlwein (1910)

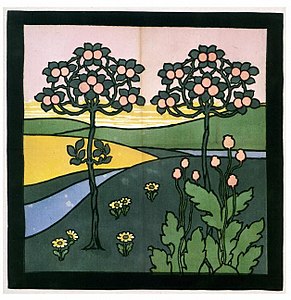

The graphic arts flourished in the Art Nouveau period, thanks to new technologies of printing, particularly color lithography which allowed the mass production of color posters. Art was no longer confined to galleries, museums and salons; it could be found on Paris walls, and in illustrated art magazines, which circulated throughout Europe and to the United States. The most popular theme of Art Nouveau posters was women; women symbolizing glamour, modernity and beauty, often surrounded by flowers.

In Britain, the leading graphic artist in the Art Nouveau style was Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898). He began with engraved book illustrations for Le Morte d'Arthur, then black and white illustrations for Salome by Oscar Wilde (1893), which brought him fame. In the same year, he began engraving illustrations and posters for the art magazine The Studio, which helped publicize European artists such as Fernand Khnopff in Britain. The curving lines and intricate floral patterns attracted as much attention as the text. [52]

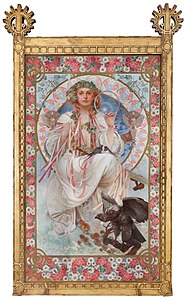

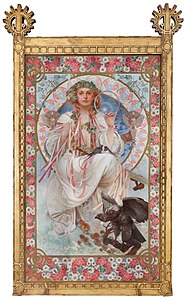

The Swiss-French artist Eugène Grasset (1845-1917) was one of the first creators of French Art Nouveau posters. He helped decorate the famous cabaret Le Chat noir in 1885 and made his first posters for the Fêtes de Paris. He made a celebrated poster of Sarah Bernhardt in 1890, and a wide variety of book illustrations. The artist-designers Jules Chéret, Georges de Feure and the painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec all made posters for Paris theaters, cafés, dance halls cabarets. The Czech artist Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939) arrived in Paris in 1888, and in 1895 made a poster for actress Sarah Bernhardt in the play Gismonda by Victorien Sardou. The success of this poster led to a contract to produce posters for six more plays by Bernhardt. Over the next four years, he also designed sets, costumes, and even jewelry for the actress.[53][54] Based on the success of his theater posters, Mucha made posters for a variety of products, ranging from cigarettes and soap to beer biscuits, all featuring an idealized female figure with an hourglass figure. He went on to design products, from jewelry to biscuit boxes, in his distinctive style. [55]

In Vienna, the most prolific designer of graphics and posters was Koloman Moser (1868-1918), who actively participated in the Secession movement with Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffmann, and made illustrations and covers for the magazine of the movement, Ver Sacrum, as well as paintings, furniture and decoration.[56]

Painting

Le Chahut by Georges Seurat (1889–90)

Le Corsage rayé by Édouard Vuillard (1895), National Gallery of Art

Beethoven Frieze in the Sezessionshaus in Vienna by Gustav Klimt (1907–08)

Watercolor and ink painting of Loie Fuller Dancing, by Koloman Moser (1902)

Slavia by Alphonse Mucha (1908)

Painting was another domain of Art Nouveau, though most painters associated with Art Nouveau are primarily described as members of other movements, particularly post-impressionism and symbolism. Alphonse Mucha was famous for his Art Nouveau posters, which frustrated him. According to his son and biographer, Jiří Mucha, he did not think much of Art Nouveau. "What is it, Art Nouveau? he asked. "...Art can never be new." [57] He took the greatest pride in his work as a history painter. His one Art-Nouveau inspired painting, "Slava", is a portrait of the daughter of his patron in Slavic costume, which was modeled after his theatrical posters. [57]

In 1892, Siegfried Bing organized an exhibition in Paris featuring seven painters, including Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Félix Vallotton, and Maurice Denis; and his Maison de l'Art Nouveau exhibited paintings by Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Eugène Grasset, Koloman Moser and Gustav Klimt also did some decorative work. However, all of these artists were primarily known for paintings in movements outside Art Nouveau. Seurat and Signac were known for Post-impressionism well before the appearance of Art Nouveau. Bonnard, Vuillard and Vallaton were members of the Post-Impressionist group of avant-garde painters Les Nabis.[58]Maurice Denis did some interior design work in the Art Nouveau style, but his easel paintings were firmly in the style of the Nabis. In Belgium, Fernand Khnopff worked in both painting and graphic design. Wall murals by Gustav Klimt were integrated into decorative scheme of Josef Hoffmann for the Palais Stoclet, but the paintings of Klimt and Khnopff are usually considered examples of symbolism rather than Art Nouveau.

One common theme of both symbolist and Art Nouveau painters of the period was the stylized depiction of women. One popular subject was the American dancer Loie Fuller, portrayed by French and Austrian painters and poster artists.[59]

Glass art

Cup Par une telle nuit by Émile Gallé, France, (1894)

Lampe aux ombelles by Émile Gallé, France, (about 1902)

Rose de France cup by Émile Gallé, (1901)

Daum vase, France, (1900)

Lamp by Daum, France (1900)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Au Nouveau Cirque, Papa Chrysanthème, c.1894, stained glass, Musée d'Orsay

Stained glass window Veranda de la Salle by Jacques Gruber (France)

Blown glass with flower design by Karl Koepping, Germany, (1896)

Glass designed by Otto Prutscher (Austria) (1909)

Window for the House of an Art Lover, by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1901)

Lily lamp by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1900-1910)

Iridescent vase by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1904)

Jack-in-the-pulpit vase, Louis Comfort Tiffany, U.S. (1913)

Stained glass window Architecture by John La Farge U.S. (1903)

Glass art was a medium in which Art Nouveau found new and varied ways of expression. Intense amount of experimentation went on, particularly in France, to find new effects of transparency and opacity: in engraving win cameo, double layers, and acid engraving, a technique which permitted production in series. The city of Nancy became an important center for the French glass industry, and the workshops of Emile Gallé and the Daum studio, led by Auguste and Antonin Daum, were located there. They worked with many notable designers, including Ernest Bussière, Henri Bergé (illustrateur), and Amalric Walter. They developed a new method of incrusting glass by pressing fragments of different color glass into the unfinished piece. They often collaborated with the furniture designer Louis Majorelle, whose home and workshops were in Nancy. Another feature of Art Nouveau was the use of stained glass windows with that style of floral themes in residential salons, particularly in the Art Nouveau houses in Nancy. Many were the work of Jacques Gruber, who made windows for the Villa Majorelle and other houses.[60]

In Belgium, the leading firm was the glass factory of Val Saint Lambert, which created vases in organic and floral forms, many of them designed by Philippe Wolfers. Wolfers was noted particularly for creating works of symbolist glass, often with metal decoration attached. In Bohemia, then a region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire noted for crystal manufacture, the companies J. & L. Lobmeyr and Joh. Loetz Witwe also experimented with new coloring techniques, producing more vivid and richer colors. In Germany, experimentation was led by Karl Köpping, who used blown glass to create extremely delicate glasses in the form of flowers; so delicate that few survive today.[61]

In Vienna, the glass designs of the Secession movement were much more geometrical than those of France or Belgium; Otto Prutscher was the most rigorous glass designer of the movement.[61]

In Britain, a number of floral stained glass designs were created by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh for the architectural display called "The House of an Art Lover."

In the United States, Louis Comfort Tiffany and his designers became particularly famous for their lamps, whose glass shades used common floral themes intricately pieced together. Tiffany lamps gained popularity after the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, where Tiffany displayed his lamps in a Byzantine-like chapel. Tiffany experimented extensively with the processes of coloring glass, patenting in 1894 the process Favrile glass, which used metallic oxides to color the interior of the molten glass, giving it an iridescent effect. His workshops produced several different series of the Tiffany lamp in different floral designs, along with stained glass windows, screens, vases and a range of decorative objects. His works were first imported to Germany, then to France by Siegfried Bing, and then became one of the decorative sensations of the 1900 Exposition. An American rival to Tiffany, Steuben Glass, was founded in 1903 in Corning, NY, by Frederick Carder, who, like Tiffany, used the Fevrile process to create surfaces with iridescent colors. Another notable American glass artist was John La Farge, who created intricate and colorful stained glass windows on both religious and purely decorative themes.[61]

Metal art

Balcony of Castel Béranger in Paris, by Hector Guimard (1897–98)

Railings by Louis Majorelle for the Bank Renauld in Nancy

Tulip candelabra by Fernand Dubois (1899)

Table Lamp by François-Raoul Larche in gilt bronze, with the dancer Loïe Fuller as model (1901)

Entrance grill of the Villa Majorelle in Nancy (1901–02)

Light fixture by Victor Horta (1903)

Cast iron Baluster by George Grant Elmslie (1899-1904)

Lamp by German architect Friedrich Adler (1903-4)

Lamp by Ernst Riegel made of silver and malachite (1905)

Gate of the Palais Stoclet by Josef Hoffmann, Brussels (1905-1911)

The 19th-century architectural theorist Viollet-le-Duc had advocated showing, rather than concealing the iron frameworks of modern buildings, but Art Nouveau architects Victor Horta and Hector Guimard went a step further: they added iron decoration in curves inspired by floral and vegetal forms both in the interiors and exteriors of their buildings. They took the form of stairway railings in the interior, light fixtures, and other details in the interior, and balconies and other ornaments on the exterior. These became some of the most distinctive features of Art Nouveau architecture. The use of metal decoration in vegetal forms soon also appeared in silverware, lamps, and other decorative items.[62]

In the United States, the designer George Grant Elmslie made extremely intricate cast iron designs for the balustrades and other interior decoration of the buildings of Chicago architect Louis Sullivan.

While French and American designers used floral and vegetal forms, Joseph Maria Olbrich and the other Secession artists designed teapots and other metal objects in a more geometric and sober style.[63]

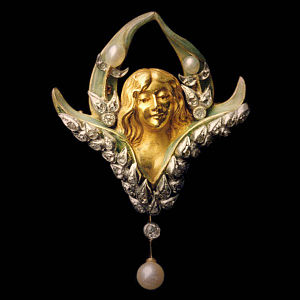

Jewelry

Carved horn decorated with pearls, by Louis Aucoc (circa 1900)

Translucent enamel flowers with small diamonds in the veins, by Louis Aucoc (circa 1900)

"Flora" brooch by Louis Aucoc (circa 1900)

A corsage ornament by Louis Tiffany (1900)

Dragonfly Lady brooch by René Lalique, made of gold, enamel, chrysoprase, moonstone, and diamonds (1897–98)

Brooch with woman by René Lalique

Necklace by Charles Robert Ashbee (1901)

Brooch of horn with enamel, gold and aquamarine by Paul Follot (1904–09)

Philippe Wolfers, Niké Brooch (1902), collection King Baudouin Foundation, depot: KMKG-MRAH

Philippe Wolfers, Chauve-Souris - Collection King Baudouin Foundation depot: KMKG-MRAH

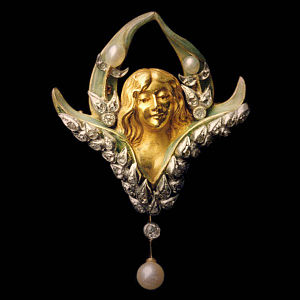

Art Nouveau is characterized done by soft, curved shapes and lines, and usually features natural designs such as flowers, birds and other animals. The female body is a popular theme and is featured on a variety of jewelry pieces, especially cameos. It frequently included long necklaces made of pearls or sterling-silver chains punctuated by glass beads or ending in a silver or gold pendant, itself often designed as an ornament to hold a single, faceted jewel of amethyst, peridot, or citrine.[64]

The Art Nouveau period brought a notable stylistic revolution to the jewelry industry, led largely by the major firms in Paris. For the previous two centuries, the emphasis in fine jewelry had been creating dramatic settings for diamonds. During the reign of Art Nouveau, diamonds usually played a supporting role. Jewelers experimented with a wide variety of other stones, including agate, garnet opal, moonstone, aquamarine and other semi-precious stones, and with a wide variety of new techniques, among others enameling, and new materials, including horn, molded glass, and ivory.

Early notable Paris jewelers in the Art Nouveau style included Louis Aucoc, whose family jewelry firm dated to 1821. The most famous designer of the Art Nouveau period, René Lalique, served his apprenticeship in the Aucoc studio from 1874 to 1876. Lalique became a central figure of Art Nouveau jewelry and glass, using nature, from dragonflies to grasses, as his model. Artists from outside of the traditional world of jewellery, such as Paul Follot, best known as a furniture designer, experimented with jewellery designs. Other notable French Art Nouveau jewellery designers included Jules Brateau and Georges Henry. In the United States, the most famous designer was Louis Comfort Tiffany, whose work was shown at the shop of Siegfried Bing and also at the 1900 Paris Exposition.

In Britain, the most prominent figure was the Liberty & Co. designer Archibald Knox, who made a variety of Art Nouveau pieces, including silver belt buckles. C. R. Ashbee designed pendants in the shapes of peacocks. The versatile Glasgow designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh also made jewellery, using traditional Celtic symbols. In Germany, the center for Jugendstil jewelry was the city of Pforzheim, where most of the German firms, including Theodor Fahrner, were located. They quickly produced works to meet the demand for the new style.

[64]

Architecture

The Hôtel Tassel in Brussels, by Victor Horta (1893-4)

Majolica House in Vienna, by Otto Wagner (1898)[65]

Casa Fenoglio-Lafleur in Turin, by Pietro Fenoglio (1902)

22, Rue du Général de Castelnau in Strasbourg, by Franz Lütke and Heinrich Backes (1903)

Casa Batlló in Barcelona, by Antoni Gaudí (1904)

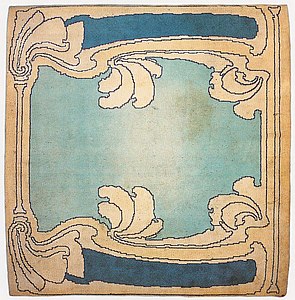

Art Nouveau architecture was a reaction against the eclectic styles which dominated European architecture in the second half of the 19th century. It was expressed through decoration. The buildings were covered with ornament in curving forms, based on flowers, plants or animals: butterflies, peacocks, swans, irises, cyclamens, orchids and water lilies. Façades were asymmetrical, and often decorated with polychrome ceramic tiles. The decoration usually suggested movement; there was no distinction between the structure and the ornament.[66]

The style first appeared in Brussels' Hôtel Tassel (1894) and Hôtel Solvay (1900) of Victor Horta. The Hôtel Tassel was visited by Hector Guimard, who used the same style in his first major work, the Castel Béranger (1897–98). In all of these houses, the architects also designed the furniture and the interior decoration, down to the doorknobs and carpeting. In 1899, based on the fame of the Castel Béranger, Guimard received a commission to design the entrances of the stations of the new Paris Métro, which opened in 1900. Though few of the originals survived, These became the symbol of the Art Nouveau movement in Paris.

In Paris, the architectural style was also a reaction to the strict regulations imposed on building facades by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the prefect of Paris under Napoleon III. Bow windows were finally allowed in 1903, and Art Nouveau architects went to the opposite extreme, most notably in the houses of Jules Lavirotte, which were essentially large works of sculpture, completely covered with decoration. An important neighborhood of Art Nouveau houses appeared in the French city of Nancy, around the Villa Majorelle (1901–02), the residence of furniture designer Louis Majorelle. It was designed by Henri Sauvage as a showcase for Majorelle's furniture designs.[67]

Furniture

Chair by Henry van de Velde, Belgium (1896)

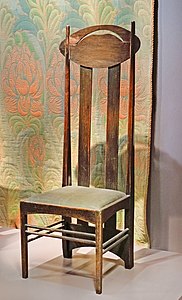

Chair by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, UK, (1897–1900)

Stool by Paul Hankar, Belgium (1898)

Wardrobe by Richard Riemerschmid, Germany (1902)

A bedroom by Louis Majorelle (1903–1904)

Dining room by Eugène Vallin, France, (1903)

Chair by Rupert Carabin, France (1895)

Furniture set by Victor Horta in the Hôtel Aubeque in Brussels (1902-1904)

Chair by Charles Rohlfs, U.S. (1898–1899)

"Snail chair" and other furniture by Carlo Bugatti, Italy, (1902)

chair by Gaspar Homar, Spain (1903)

"Dawn and Dusk" bed by Émile Gallé, France (1904)

Adjustable armchair Model 670 "Sitting Machine" designed by Josef Hoffmann, Austria (1904–1906)

Victor Horta, furniture from Turin. Collection King Baudouin Foundation.

Furniture design in the Art Nouveau period was closely associated with the architecture of the buildings; the architects often designed the furniture, carpets, light fixtures, doorknobs, and other decorative details. The furniture was often complex and expensive; a fine finish, usually polished or varnished, was regarded as essential, and continental designs were usually very complex, with curving shapes that were expensive to make. It also had the drawback that the owner of the home could not change the furniture or add pieces in a different style without disrupting the entire effect of the room. For this reason, when Art Nouveau architecture went out of style, the style of furniture also largely disappeared.

In France, the center for furniture design and manufacture was in Nancy, where two major designers, Émile Gallé and Louis Majorelle had their studios and workshops, and where the Alliance des industries d'art (later called the School of Nancy) had been founded in 1901. Both designers based on their structure and ornamentation on forms taken from nature, including flowers and insects, such as the dragonfly, a popular motif in Art Nouveau design. Gallé was particularly known for his use of marquetry in relief, in the form of landscapes or poetic themes. Majorelle was known for his use of exotic and expensive woods, and for attaching bronze sculpted in vegetal themes to his pieces of furniture. Both designers used machines for the first phases of manufacture, but all the pieces were finished by hand. Other notable furniture designers of the Nancy School included Eugène Vallin and Émile André; both were architects by training, and both designed furniture that resembled the furniture from Belgian designers such as Horta and Van de Velde, which had less decoration and followed more closely the curving plants and flowers. Other notable French designers included Henri Bellery-Desfontaines, who took his inspiration from the neo-Gothic styles of Viollet-le-Duc; and Georges de Feure, Eugène Gaillard, and Édouard Colonna, who worked together with art dealer Siegfried Bing to revitalize the French furniture industry with new themes. Their work was known for "abstract naturalism", its unity of straight and curved lines, and its rococo influence. The furniture of de Feure at the Bing pavilion won a gold medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition. The most unusual and picturesque French designer was François-Rupert Carabin, a sculptor by training, whose furniture featured sculpted nude female forms and symbolic animals, particularly cats, who combined Art Nouveau elements with Symbolism. Other influential Paris furniture designers were Charles Plumet, and Alexandre Charpentier.[68] In many ways the old vocabulary and techniques of classic French 18th-century Rococo furniture were re-interpreted in a new style.[5]

In Belgium, the pioneer architects of the Art Nouveau movement, Victor Horta and Henry van de Velde, designed furniture for their houses, using vigorous curving lines and a minimum of decoration. The Belgian designer Gustave Serrurier-Bovy added more decoration, applying brass strips in curving forms. In the Netherlands, where the style was called Nieuwe Kunst or New Art, H.P. Berlag, Lion Cachet and Theodor Nieuwenhuis followed a different course, that of the English Arts and Crafts movement, with more geometric rational forms.

In Britain, the furniture of Charles Rennie Mackintosh was purely Arts and Crafts, austere and geometrical, with long straight lines and right angles and a minimum of decoration.[69] Continental designs were much more elaborate, often using curved shapes both in the basic shapes of the piece, and in applied decorative motifs. In Germany, the furniture of Peter Behrens and the Jugendstil was largely rationalist, with geometric straight lines and some decoration attached to the surface. Their goal was exactly the opposite of French Art Nouveau; simplicity of structure and simplicity of materials, for furniture that could be inexpensive and easily mass-manufactured. The same was true for the furniture of designers of the Wiener Werkstätte in Vienna, led by Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffmann, Josef Maria Olbrich and Koloman Moser. The furniture was geometric and had a minimum of decoration, though in style it often followed national historic precedent, particularly the Biedemeier style.[70]

Italian and Spanish furniture design went off in their own direction. Carlo Bugatti in Italy designed the extraordinary Snail Chair, wood covered with painted parchment and copper, for the Turin International Exposition of 1902. In Spain, following the lead of Antoni Gaudi and the Modernismo movement, the furniture designer Gaspar Homar designed works that were inspired by natural forms with touches of Catalan historic styles.[37]

In the United States, furniture design was more often inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement, or by historic American models, than by the Art Nouveau. One designer who did introduce Art Nouveau themes was Charles Rohlfs in Buffalo, New York, whose designs for American white oak furniture were influenced by motifs of Celtic Art and Gothic art, with touches of Art Nouveau in the metal trim applied to the pieces.[37]

Ceramics

Porcelain vase by Ernest Chaplet, France, (about 1900)

Vase by Maurice Dufrêne, France, (1900)

Bowl by Auguste Delaherche, Paris, (1901)

Edmond Lachenal, vase, France (1902)

Limoges enamel by Paul Bonnaud, France (1903)

Sèvres porcelain figurine, Dancer with Scarf by Agathon Léonard, France, (1900)

Faience vase by Thorvald Bindesboll, Denmark, (1893)

Vase by Alf Wallander, Sweden (1897)

Vase with copper ornaments by the Rosenthal ceramics factory, Bavaria, Germany, (1900)

Porcelain stoneware punch bowl by Richard Riemerschmid, Germany, (1902)

Ceramic facade decoration of Lavirotte Building by Alexandre Bigot, Paris (1901)

Ceramic tile façade decoration by Galileo Chini, Italy, (1904)

Vase by József Rippl-Rónai Hungary, (1900)

Vase with vines and snails by Pál Horti, Hungary (1900)

Glazed earthenware pot by the Grueby Faience Company of Boston (1901)

Amphora with elm-leaf and blackberry manufactured by Stellmacher & Kessner

Rookwood Pottery Company vase of ceramic overlaid with silver by Kataro Shirayamadani, U.S., (1892)

Rookwood Pottery Company vase by Carl Schmidt (1904)

The last part of the 19th century saw many technological innovation in the manufacture of ceramics, particularly the development of high temperature (grand feu) porcelain with crystallised and matte glazes. At the same time, several lost techniques, such as oxblood glaze, were rediscovered. Art Nouveau ceramics were also influenced by traditional and modern Japanese and Chinese ceramics, whose vegetal and floral motifs fitted well with the Art Nouveau style. In France, artists also rediscovered the traditional grés methods and reinvented them with new motifs. Ceramics also found an important new use in architecture: Art Nouveau architects, Jules Lavirotte and Hector Guimard among them, began to decorate the façades of buildings with ceramic tiles, many of them made by the firm of Alexandre Bigot, giving them a distinct Art Nouveau sculptural look. In the Art Nouveau ceramics quickly moved into the domain of sculpture and architecture.[71]

One of the pioneer French Art Nouveau ceramists was Ernest Chaplet, whose career in ceramics spanned thirty years. He began producing stoneware influenced by Japanese and Chinese prototypes. Beginning in 1886, he worked with painter Paul Gauguin on stoneware designs with applied figures, multiple handles, painted and partially glazed, and collaborated with sculptors Félix Bracquemond, Jules Dalou and Auguste Rodin. His works were acclaimed at the 1900 Exposition.

The major national ceramics firms had an important place at the 1900 Paris Exposition: the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres outside Paris; Nymphenburg, Meissen, Villeroy & Boch in Germany, and Doulton in Britain. Other leading French ceramists included Taxile Doat, Pierre-Adrien Dalpayrat, Edmond Lachenal, Albert Dammouse and Auguste Delaherche.[72]

In France, Art Nouveau ceramics sometimes crossed the line into sculpture. The porcelain figurine Dancer with a Scarf by Agathon Léonard, made for the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres, won recognition in both categories at the 1900 Paris Exposition.

The Zsolnay factory in Pécs, Hungary, was led by Miklós Zsolnay (1800–1880) and his son, Vilmos Zsolnay (1828–1900,) with Tádé Sikorski (1852–1940) chief designer, to produce stoneware and other ceramics in 1853. In 1893, Zsolnay introduced porcelain pieces made of eosin. He led the factory to worldwide recognition by demonstrating its innovative products at world fairs and international exhibitions, including the 1873 World Fair in Vienna, then at the 1878 World Fair in Paris, where Zsolnay received a Grand Prix. Frost-resisting Zsolnay building decorations were used in numerous buildings, specifically during the Art Nouveau movement.[73]

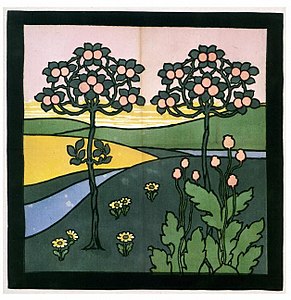

Textiles and wallpaper

Silk and wool tapestry design, Cyclamen, by Hermann Obrist, an early example of the "whiplash" motif (1895)

Page on the Water Lily, from the book by Eugène Grasset on ornamental uses of flowers (1899)

Textile design by Koloman Moser (1899)

Printed cotton from the Silver Studio, for Liberty department store, U.K. (1904)

The Shepherd tapestry by János Vaszary (1906) combined Art Nouveau motifs and a traditional Hungarian folk theme

Victor Horta, tapis, collection King Baudouin Foundation.

Textiles and wallpapers were an important vehicle of Art Nouveau from the beginning of the style, and an essential element of Art Nouveau interior design. In Britain, the textile designs of William Morris had helped launch the Arts and Crafts Movement and then Art Nouveau. Many designs were created for the Liberty department store in London, which popularized the style throughout Europe. One such designer was the Silver Studio, which provided colorful stylized floral patterns. Other distinctive designs came from Glasgow School, and Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh. The Glasgow school introduced several distinctive motifs, including stylized eggs, geometric forms and the "Rose of Glasgow".

In France, a major contribution was made by designer Eugène Grasset who in 1896 published La Plante et ses applications ornamentales, suggesting Art Nouveau designs based on different flowers and plants. Many patterns were designed for and produced by for the major French textile manufacturers in Mulhouse, Lille and Lyon, by German and Belgian workshops. The German designer Hermann Obrist specialized in floral patterns, particularly the cyclamen and the "whiplash" style based on flower stems, which became a major motif of the style. The Belgian Henry van de Velde presented a textile work, La Veillée d'Anges, at the Salon La Libre Esthéthique in Brussels, inspired by the symbolism of Paul Gauguin and of the Nabis. In the Netherlands, textiles were often inspired by batik patterns from the Dutch colonies in the East Indies. Folk art also inspired the creation of tapestries, carpets, embroidery and textiles in Central Europe and Scandinavia, in the work of Gerhard Munthe and Frida Hansen in Norway. The Five Swans design of Otto Eckmann appeared in more than one hundred different versions. The Hungarian designer János Vaszary combined Art Nouveau elements with folkloric themes.[74]

See also

- Fin de siècle

- Belle Époque

- Secession (art)

- Paris architecture of the Belle Époque

- Réseau Art Nouveau Network

- Second Industrial Revolution

- Deutscher Werkbund

- Charles-Léonce Brossé

- Aestheticism

References

^ Sterner (1982), 6.

^ Henry R. Hope, review of H. Lenning, The Art Nouveau, The Art Bulletin, vol. 34 (June 1952), 168–171 (esp. 168–169): Discussing the state of Art Nouveau during 1952, the author notes that Art Nouveau, which had become disfavored, was not yet an acceptable study for serious art history or a subject suitable for major museum exhibitions and their respective catalogs. He predicts an impending change, however.

^ abcde Michèle Lavallée, "Art Nouveau", Grove Dictionary of Art, Oxford University Press [accessed 11 April 2008.

^ abcde Duncan (1994): 23–24.

^ abcde Gontar, Cybele. Art Nouveau. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 (October 2006)

^ Bouillon, Jean-Paul, Journal de l'Art Nouveau (1985), p. 6

^ Viollet le-Duc, Entretiens sur l'architecture

^ Bouillon 1985, p. 24.

^ Interview in L'Écho de Paris, 28 December 1891, cited in Bouillon (1985)

^ Bouillon 1985, p. 26.

^ Lahor 2007, p. 30.

^ Bouillon 1985.

^ Lahor 2007, p. 127.

^ Martin Eidelberg and Suzanne Henrion-Giele, "Horta and Bing: An Unwritten Episode of L'Art Nouveau", The Burlington Magazine, vol. 119, Special Issue Devoted to European Art Since 1890 (Nov. 1977), pp. 747–752.

^ Duncan (1994), pp. 15–16, 25–27.

^ Texier 2012, pp. 86–87.

^ Lahor, L'Art Nouveau, p. 91.

^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Major Town Houses of the Architect Victor Horta (Brussels)". whc.unesco.org..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Sterner (1982), pp. 38–42.

^ ab Riley 2004, p. 323.

^ Lahor, L'Art Nouveau, p. 104

^ Duncan (1994), p. 37.

^ "Art Nouveau - Art Nouveau Art". 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013.

^ Lahor, p. 160.

^ Muter, Grant (1985). "Leon Solon and John Wadsworth". Journal of the Decorative Arts Society. JSTOR 41809144.

^ He was commissioned by the Wardle family of dyers and printers, trading as "Thomas Wardle & Co" and "Bernard Wardle and Co".The Wardel Pattern Books RevealedArchived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

^ A. Philip McMahon, "review of F. Schmalenbach, Jugendstil", Parnassus, vol. 7 (Oct., 1935), 27.

^ Reinhold Heller, "Recent Scholarship on Vienna's "Golden Age", Gustav Klimt, and Egon Schiele", The Art Bulletin, vol. 59 (Mar., 1977), pp. 111–118.

^ Lahor 2007, p. 52.

^ Lahor 2007, p. 63.

^ Lahor 2007, p. 120.

^ Riley 2007, p. 310.

^ Lahor 2007, p. 142.

^ James Grady, Special Bibliographical Supplement: A Bibliography of the Art Nouveau, in "The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians", vol. 14 (May, 1955), pp. 18–27.

^ abc Duncan (1994): 52.

^ Riley 2007, p. 311.

^ abc Riley 2007, p. 312.

^ "The Charm of Old Helsinki — VisitFinland.com".

^ "Art Nouveau European Route : Cities". www.artnouveau.eu.

^ Duncan, Alistair, Art déco, Thames and Hudson (1988), pp. 147–48

^ Lahor 2007, p. 167.

^ ab Duncan (1994): 27–28.

^ ab Duncan (1994): 10–13.

^ abc Duncan (1994): 14–18.

^ Before opening the Maison de l'Art Nouveau, Bing managed a shop specialising in items from Japan; after 1888, he promoted Japanism with his magazine Le Japon artistique: Duncan (1994): 15–16.

^ Sterner (1982), 21.

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 2010-06-30.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link) Edmond Lachenal produced editions of Rodin's sculptures

^ Jennifer Opie, A Dish by Thorvald Bindesbøll, in The Burlington Magazine, vol. 132 (May, 1990), pp. 356.

^ Claire Selkurt, "New Classicism: Design of the 1920s in Denmark", in The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, vol. 4 (Spring, 1987), pp. 16–29 (esp. 18 n. 4).

^ Danuta A. Boczar, The Polish Poster, in Art Journal, vol. 44 (Spring, 1984), pp. 16–27 (esp. 16).

^ Danuta Batorska, "Zofia Stryjeńska: Princess of Polish Painting", in Woman's Art Journal, vol. 19 (Autumn, 1998–Winter, 1999), pp. 24–29 (esp. 24–25).

^ Lahor 2007, p. 99.

^ An Introduction to the Work of Alphonse Mucha and Art Nouveau, lecture by Ian Johnston of Malaspina University-College, Nanaimo, British Columbia.