Baroque

Baldachino of St. Peter's Basilica by Bernini; Louis XIV by Bernini;Adoration of the Magi by Peter Paul Rubens; Wieskirche, Bavaria | |

| Years active | 17th–18th century |

|---|---|

| Country | Europe and Latin America |

The Baroque (UK: /bəˈrɒk/, US: /bəˈroʊk/) is a highly ornate and often extravagant style of architecture, art and music that flourished in Europe from the early 17th until the mid-18th century. It followed the Renaissance style and preceded the Rococo (in the past often referred to as "late Baroque") and Neoclassical styles. It was encouraged by the Catholic Church as a means to counter the simplicity and austerity of Protestant architecture, art and music, though Lutheran Baroque art developed in parts of Europe as well.[1] The Baroque style used contrast, movement, exuberant detail, deep colour, grandeur and surprise to achieve a sense of awe. The style began at the start of the 17th century in Rome, then spread rapidly to France, northern Italy, Spain and Portugal, then to Austria and southern Germany. By the 1730s, it had evolved into an even more flamboyant style, called rocaille or Rococo, which appeared in France and central Europe until the mid to late 18th century.

Contents

1 Origin of word

2 Architecture: origins and characteristics

2.1 Italian Baroque architecture

2.2 Spanish Baroque architecture

2.3 Central Europe and Rococo (1740s–1770s)

2.4 French Baroque or Classicism

2.5 Russian Baroque

3 Painting

4 Sculpture

5 Music and ballet

5.1 Composers and examples

6 Theatre

7 End of the style, condemnation and academic rediscovery

8 Italian Baroque

9 Spanish Baroque

10 Baroque and Rococo in Germany, Austria and Central Europe

11 Style Louis XIV

12 See also

13 Notes

14 Books cited in text

15 Further reading

16 External links

Origin of word

The word 'barroco' was a Portuguese term for a pearl with an irregular shape. Cognates for the term in other Romance languages include: barroco in Spanish,[2], barocco in Italian. and baroque in French. [3] The French term was used to describe pearls in a 1531 inventory of Charles V's treasures. [4]

Another suggested origin of the term is the philosophical term baroco, used in French to describe a particularly elaborate and convoluted argument. It was a Mnemonic word, used to memorize the terms of one particular syllogism of Aristotle; the fourth syllogism of the second figure of twenty-four modes. An example of a Baroco is: "All P is S, but some F is not S. Therefore S is not P." [5]

In the 18th century, the term was usually used to describe music, and was not flattering. In an anonymous satirical review of the première of Jean-Philippe Rameau's Hippolyte et Aricie in October 1733, which was printed in the Mercure de France in May 1734, the critic wrote that the novelty in this opera was "du barocque", complaining that the music lacked coherent melody, was unsparing with dissonances, constantly changed key and meter, and speedily ran through every compositional device.[6]

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was a musician and composer as well as philosopher, wrote in 1768 in the Encyclopédie: "Baroque music is that in which the harmony is confused, and loaded with modulations and dissonances. The singing is harsh and unnatural, the intonation difficult, and the movement limited. It appears that term comes from the word 'baroco' used by logicians."[7]

The word was first used to describe the period of art that followed the Renaissance in 1855 by the Swiss art historian Jacob Burckhardt in an article in the journal Le Cicerone. He used the term to attack the movement for subverting the values of the Renaissance.[8] The term "style baroque" did not enter into the dictionary of the Académie française until 1878, when it lost its original negative connotation.[9] In 1888, the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin published the first serious academic work on the style, Renaissance und Barock, which described the differences between the painting, sculpture, and architecture of the Renaissance and the Baroque.[10]

Architecture: origins and characteristics

Quadratura or trompe-l'œil ceiling of the Church of the Jesu, Rome, by Giovanni Battista Gaulli (1669–1683)

The Baroque style of architecture was a result of doctrines adopted by the Catholic Church at the Council of Trent in 1545–63, in response to the Protestant Reformation. The first phase of the Counter-Reformation had imposed a severe, academic style on religious architecture, which had appealed to intellectuals but not the mass of churchgoers. The Council of Trent decided instead to appeal to a more popular audience, and declared that the arts should communicate religious themes with direct and emotional involvement.[11][12]Lutheran Baroque art developed as a confessional marker of identity, in response to the Great Iconoclasm of Calvinists.[13]

Baroque churches were designed with a large central space, where the worshippers could be close to the altar, with a dome or cupola high overhead, allowing light to illuminate the church below. The dome was one of the central symbolic features of baroque architecture illustrating the union between the heavens and the earth, The inside of the cupola was lavishly decorated with paintings of angels and saints, and with stucco statuettes of angels, giving the impression to those below of looking up at heaven.[14]

Another feature of baroque churches are the quadratura; trompe-l'œil paintings on the ceiling in stucco frames, either real or painted, crowded with paintings of saints and angels and connected by architectural details with the balustrades and consoles. Quadratura paintings of Atlantes below the cornices appear to be supporting the ceiling of the church. Unlike the painted ceilings of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, which combined different scenes, each with its own perspective, to be looked at one at a time, the Baroque ceiling paintings were carefully created so the viewer on the floor of the church would see the entire ceiling in correct perspective, as if the figures were real.

The interiors of baroque churches became more and more ornate in the High Baroque, and focused around the altar, usually placed under the dome. The most celebrated baroque decorative works of the High Baroque are the Chair of Saint Peter (1647–53) and the Baldachino of St. Peter (1623–34), both by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. The Baldequin of St. Peter is an example of the balance of opposites in Baroque art; the gigantic proportions of the piece, with the apparent lightness of the canopy; and the contrast between the solid twisted columns, bronze, gold and marble of the piece with the flowing draperies of the angels on the canopy.[15] The Dresden Frauenkirche serves as a prominent example of Lutheran Baroque art, which was completed in 1743 after being commissioned by the Lutheran city council of Dresden and was "compared by eighteenth-century observers to St Peter’s in Rome".[1]

The twisted column in the interior of churches is one of the signature features of the Baroque. It gives both a sense of motion and also a dramatic new way of reflecting light.

The cartouche was another characteristic feature of baroque decoration. These were large plaques carved of marble or stone, usually oval and with a rounded surface, which carried images or text in gilded letters, and were placed as interior decoration or above the doorways of buildings, delivering messages to those below. They showed a wide variety of invention, and were found in all types of buildings, from cathedrals and palaces to small chapels.[16]

Baroque architects sometimes used forced perspective to create illusions. For the Palazzo Spada in Rome, Borromini used columns of diminishing size, a narrowing floor and a miniature statue in the garden beyond to create the illusion that a passageway was thirty meters long, when it was actually only seven meters long. A statue at the end of the passage appears to be life-size, though it is only sixty centimeters high. Borromini designed the illusion with the assistance of a mathematician.

Italian Baroque architecture

Facade of St. Peter's Basilica (early 17th century)

Santa Maria della Salute, Venice (1631–1687)

The first building in Rome to have a Baroque facade was the Church of the Gesù in 1584; it was plain by later Baroque standards, but marked a break with the traditional Renaissance facades that preceded it. The interior of this church remained very austere until the high Baroque, when it was lavishly ornamented.

In Rome in 1605, Paul V became the first of series of popes who commissioned basilicas and church buildings designed to inspire emotion and awe through a proliferation of forms, and a richness of colors and dramatic effects.[17] Among the most influential monuments of the Early Baroque were the facade of St. Peter's Basilica (1606–1619), and the new nave and loggia which connected the facade to Michelangelo's dome in the earlier church. The new design created a dramatic contrast between the soaring dome and the disproportionately wide facade, and the contrast on the facade itself between the Doric columns and the great mass of the portico.[18]

In the mid to late 17th century the style reached its peak, later termed the High Baroque. Many monumental works were commissioned by Popes Urban VIII and Alexander VII. The sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini designed a new quadruple colonnade around St. Peter's Square (1656 to 1667). The three galleries of columns in a giant ellipse balance the oversize dome and give the Church and square a unity and the feeling of a giant theater.[19]

Another major innovator of the Italian High Baroque was Francesco Borromini, whose major work was the Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane or Saint Charles of the Four Fountains (1634–46). The sense of movement is given not by the decoration, but by the walls themselves, which undulate and by concave and convex elements, including an oval tower and balcony inserted into a concave traverse. The interior was equally revolutionary; the main space of the church was oval, beneath an oval dome.[19]

Painted ceilings, crowded with angels and saints and trompe-l'œil architectural effects, were an important feature of the Italian High Baroque. Major works included The Entry of Saint Ignace into Paradise by Andrea Pozzo (1685–1695) in the Church of Saint Ignatius in Rome, and The triumph of the name of Jesus by Giovanni Battista Gaulli in the Church of the Gesù in Rome (1669–1683), which featured figures spilling out of the picture frame and dramatic oblique lighting and light-dark contrasts.[20]

The style spread quickly from Rome to other regions of Italy: It appeared in Venice in the church of Santa Maria della Salute (1631–1687) by Baldassare Longhena, a highly original octagonal form crowned with an enormous cupola. It appeared also in Turin, notably in the Chapel of the Holy Shroud (1668–1694) by Guarino Guarini. The style also began to be used in palaces; Guarini designed the Palazzo Carignano in Turin, while Longhena designed the Ca' Rezzonico on the Grand Canal, (1657), finished by Giorgio Massari with decorated with paintings by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.[21] A series of massive earthquakes in Sicily required the rebuilding of most of them and several were built in the exuberant late Baroque or Rococo style.

Spanish Baroque architecture

The towers of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela by Fernando de Casas Novoa (1680 (center tower) and 1738–50)

Palace of San Telmo, Seville (1682)

The Catholic Church in Spain, and particularly the Jesuits, were the driving force of Spanish Baroque architecture. The first major work in the style was the San Isidro Chapel in Madrid, begun in 1643 by Pedro de la Torre. It contrasted an extreme richness of ornament on the exterior with simplicity in the interior, divided into multiple spaces and using effects of light to create a sense of mystery.[22] The Cathedral in Santiago de Compostela was modernized with a series of Baroque additions beginning at the end of the 17th century, starting with a highly-ornate bell tower (1680), then flanked by two even taller and more ornate towers, called the Obradorio, added between 1738 and 1750 by Fernando de Casas Novoa. Another landmark of the Spanish Baroque is the chapel tower of the Palace of San Telmo in Seville by Leonardo de Figueroa.[23]

Granada had only been liberated from the Moors in the 15th century, and had its own distinct variety of Baroque. The painter, sculptor and architect Alonso Cano designed the Baroque interior of Granada Cathedral between 1652 and his death in 1657. It features dramatic contrasts of the massive white columns and gold decor.

Some of the most and ornamental and lavishly decorated architecture of the period was designed by the brothers Churriguera, who worked primarily in Salamanca and Madrid. The Church of San Esteban in Salamanca (1693) is one of the most ornate baroque churches anywhere. Their other works include the buildings on the city's main square, the Plaza Mayor of Salamanca (1729).[23]

Other notable Spanish baroque architects of the late Baroque include Pedro de Ribera, a pupil of Churriguera, who designed the Royal Hospice of San Fernando in Madrid, and Narciso Tomé, who designed the celebrated El Transparente altarpiece at Toledo Cathedral (1729–32) which gives the illusion, in certain light, of floating upwards.[23]

The architects of the Spanish Baroque had an effect far beyond Spain; their work was highly influential in the churches built in the Spanish colonies in Latin America and the Philippines. The Church built by the Jesuits for a college in Tepotzotlán, with its ornate Baroque facade and tower, is a good example.[24]

Central Europe and Rococo (1740s–1770s)

St. Nicholas Church (Malá Strana) Prague (1704–1755)

Karlskirche, Vienna, by Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach (1732–1737)

The Wiesekirche in Bavaria by Dominikus Zimmermann (1745–1754)

From 1680 to 1750, many highly ornate cathedrals, abbeys, and pilgrimage churches were built in central Europe, in Bavaria, Austria, and what is now the Czech Republic. Some were in Rococo style, a distinct, more flamboyant and asymmetric style which emerged out of the Baroque, then replaced it in Central Europe in the first half of the 18th century, until it was replaced in turn by classicism.[25]

The princes of the multitude of states in that region also chose Baroque or Rococo for their palaces and residences, and often used Italian-trained architects to construct them.[26] Notable architects included Johann Fischer von Erlach, Lukas von Hildebrandt and Dominikus Zimmermann in Bavaria, Balthasar Neumann in Bruhl, and Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann in Dresden. In Prussia, Frederic II of Prussia was inspired the Grand Trianon of the Palace of Versailles, and used it as the model for his summer residence, Sanssouci, in Potsdam, designed for him by Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff (1745–1747). Another work of baroque palace architecture is the Zwinger in Potsdam, the former orangerie of the palace of the Dukes of Saxony in the 18th century.

One of the best examples of a rococo church is the Basilika Vierzehnheiligen, or Basilica of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, a pilgrimage church located near the town of Bad Staffelstein near Bamberg, in Bavaria, southern Germany. The Basilica was designed by Balthasar Neumann and was constructed between 1743 and 1772, its plan a series of interlocking circles around a central oval with the altar placed in the exact center of the church. The interior of this church illustrates the summit of Rococo decoration.[27]

Another notable example of the style is the Pilgrimage Church of Wies (German: Wieskirche). It was designed by the brothers J. B. and Dominikus Zimmermann. It is located in the foothills of the Alps, in the municipality of Steingaden in the Weilheim-Schongau district, Bavaria, Germany.Construction took place between 1745 and 1754, and the interior was decorated with frescoes and with stuccowork in the tradition of the Wessobrunner School. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Another notable example is the St. Nicholas Church (Malá Strana) in Prague (1704–55), built by Christoph Dientzenhofer and his son Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer. Decoration covers all of walls of interior of the church. The altar is placed in the nave beneath the central dome, and surrounded by chapels, Light comes down from the dome above and from the surrounding chapels. The altar is entirely surrounded by arches, columns, curved balustrades and pilasters of colored stone, which are richly decorated with statuary, creating a deliberate confusion between the real architecture and the decoration. The architecture is transformed into a theater of light, color and movement.[15]

French Baroque or Classicism

Chateau de Balleroy by François Mansart (1626–1636)

Palace of Versailles (begun by Louis Le Vau in 1661)

France largely resisted the ornate baroque style of Italy, Spain, Vienna and the rest of Europe. The French Baroque style (often termed Grand Classicism or simply Classicism in France) is closely associated with the works built for Louis XIV and Louis XV; it features more geometric order and measure than baroque, and less elaborate decoration on the facades and in the interiors. Louis XIV invited the master of baroque, Bernini, to submit a design for the new wing of the Louvre, but rejected it in favor of a more classical design by Claude Perrault and Louis Le Vau.[28]

The principal architects of the style included François Mansart (Chateau de Balleroy, 1626–1636), Pierre Le Muet (Church of Val-de-Grace, 1645–1665), Louis Le Vau (Vaux-le-Vicomte, 1657–1661) and especially Jules Hardouin Mansart and Robert de Cotte, whose work included the Galerie des Glaces and the Grand Trianon at Versailles (1687–1688). Mansart was also responsible for the Baroque-classicism of the Place Vendôme (1686–1699).[29]

The major work of the period was the Palace of Versailles, begun in 1661 by Le Vau with decoration by the painter Charles Le Brun. The gardens were designed by André Le Nôtre specifically to complement and amplify the architecture. The Galerie des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors), the centerpiece of the château, with paintings by Le Brun, was constructed between 1678 and 1686. Mansart completed the Grand Trianon in 1687. The chapel, designed by de Cotte, was finished in 1710. Following the death of Louis XIV, Louis XV added the more intimate Petit Trianon and the highly ornate theater. The fountains in the gardens were designed to be seen from the interior, and to add to the dramatic effect. The palace was admired and copied by other monarchs of Europe, particularly Peter the Great of Russia, who visited Versailles early in the reign of Louis XV, and built his own version at Peterhof Palace near Saint Petersburg, between 1705 and 1725.[30]

Russian Baroque

The Catherine Palace by Bartolomeo Rastrelli (1752-)

The Great Church of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, by Rastrelli (1753–1759)

The debut of Russian Baroque, or Petrine Baroque, followed a long visit of Peter the Great to western Europe in 1697–98, where he visited the Chateaux of Fontainebleu and Versailles and other architectural monuments. He decided, on his return to Russia, to construct similar monuments in St. Petersburg, when he moved the Russian capital there in 1712. Early major monuments in the Petrine baroque include the Peter and Paul Cathedral and Menshikov Palace.

During the reign of Empress Anna and Elizaveta Petrovna, Russian architecture was dominated by the luxurious baroque style of Bartolomeo Rastrelli; called Elizabethan Baroque. Rastrelli's signature buildings include the Winter Palace, the Catherine Palace and the Smolny Cathedral. Other distinctive monuments of the Elizabethan Baroque are the bell tower of the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra and the Red Gate.[31]

Painting

The Raising of the Cross by Peter Paul Rubens (1610–1611)

Las Meninas (1656) by Diego Velázquez

Quadratura; a painted dome by Andrea Pozzo for the Jesuit Church, Vienna, giving the illusion of looking upwards at heavenly figures around a nonexistent dome (1703)

Baroque painters worked deliberately to set themselves apart from the painters of the Renaissance and the Mannerism period after it. In their palette, they used intense and warm colors, and particularly made use of the primary colors red, blue and yellow, frequently putting all three in close proximity.[32] In their lighting, they avoided the even lighting of Renaissance painting and used strong contrasts of light and darkness on certain parts of the picture to direct attention to the central actions or figures. In their composition, they avoided the tranquil scenes of Renaissance paintings, and chose the moments of the greatest movement and drama. Unlike the tranquil faces of Renaissance paintings, the faces in Baroque paintings clearly expressed their emotions. They often used asymmetry, with action occurring away from the center of the picture, and created axes that were neither vertical or horizontal, but slanting to the left or right, giving a sense of instability and movement. They enhanced this impression of movement by having the costumes of the personages blown by the wind, or moved by their own gestures. The overall impressions were movement, emotion and drama.[33] Another essential element of baroque painting was allegory; every painting told a story and had a message, often encrypted in symbols and allegorical characters, which an educated viewer was expected to know and read.[34]

The Toilet of Venus by François Boucher (1755)

The earliest Baroque painters were the Italians the Caracci brothers, Annibale and Agostino, in the last score of the 16th century, and Caravaggio in the last decade of the century. Caravaggio's realistic approach to the human figure, painted directly from life and dramatically spotlit against a dark background, shocked his contemporaries and opened a new chapter in the history of painting. Other major painters associated closely with the Baroque style include Guido Reni, Domenichino, Andrea Pozzo, and Paolo de Matteis in Italy; Francisco de Zurbarán and Diego Velázquez in Spain; Adam Elsheimer in Germany; and Nicolas Poussin and Georges de La Tour in France (though Poussin spent most of his working life in Italy). Poussin and La Tour adopted a "classical" Baroque style with less focus on emotion and greater attention to the line of the figures in the painting than colour.

Peter Paul Rubens was the most important painter of the Flemish Baroque style. Rubens' highly charged compositions reference erudite aspects of classical and Christian history. His unique and immensely popular Baroque style emphasized movement, color, and sensuality, which followed the immediate, dramatic artistic style promoted in the Counter-Reformation. Rubens specialized in making altarpieces, portraits, landscapes, and history paintings of mythological and allegorical subjects.

One important domain of Baroque painting was Quadratura, or paintings in trompe-l'oeil, which literally "fooled the eye". These were usually painted on the stucco of ceilings or upper walls and balustrades, and gave the impression to those on the ground looking up were that they were seeing the heavens populated with crowds of angels, saints and other heavenly figures, set against painted skies and imaginary architecture.[35]

In Italy, artists often collaborated with architects on interior decoration; Pietro da Cortona was one of the painters of the 17th century who employed this illusionist way of painting. Among his most important commissions were the frescoes he painted for the Palace of the Barberini family (1633–39), to glorify the reign of Pope Urban VIII. Pietro da Cortona’s compositions were the largest decorative frescoes executed in Rome since the work of Michelangelo at the Sistine Chapel. .[36]

François Boucher was an important figure in the more delicate French Rococo style, which appeared during the late Baroque period. He designed tapestries, carpets and theater decoration as well as painting. His work was extremely popular with Madame Pompadour, the Mistress of King Louis XV. His paintings featured mythological romantic, and mildly erotic themes.[37]

Sculpture

Ecstasy of St. Teresa, by Bernini (1647–1652)

Bust of Louis XIV by Bernini, Versailles (1665)

The dominant figure in baroque sculpture was Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Under the patronage of Pope Urban VIII, he made a remarkable series of monumental statues of saints and figures whose faces and gestures vividly expressed their emotions, as well as portrait busts of exceptional realism, and highly decorative works for the Vatican, including the imposing Chair of St. Peter beneath the dome in St. Peter's Basilica. In addition, he designed fountains with monumental groups of sculpture to decorate the major squares of Rome.[38]

Baroque sculpture was particularly inspired by ancient Roman statuary, particularly by the famous statue of Laocoön from the First Century A.D., which was on display in the gallery of the Vatican. When he visited Paris in 1665, Bernini addressed the students at the Academy of painting and sculpture, he advised the students to work from classical models, rather than from nature. He told the students, "When I had trouble with my first statue, i consulted the Antinous like an oracle."[39]

Notable late French baroque sculptors included Étienne Maurice Falconet and Jean Baptiste Pigalle. Pigalle was commissioned by Frederick the Great to make statues for Frederick's own version of Versailles at Sanssouci in Potsdam, Germany. Falconet also received an important foreign commission, creating the famous statue of Peter the Great on horseback found in St. Petersburg.

In Spain, the sculptor Francisco Salzillo worked exclusively on religious themes, using polychromed wood. Some of the finest baroque sculptural craftsmanship was found in the gilded stucco altars of churches of the Spanish colonies of the New World, made by local craftsmen; examples include the Rosary Chapel of the Church of Santo Domingo in Oaxaca, Mexico (1724–31).

Music and ballet

Louis XIV in costume for the Ballet Royal de la Nuit (1653)

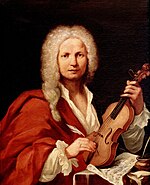

Antonio Vivaldi, (1678–1741)

The term Baroque is also used to designate the style of music composed during a period that overlaps with that of Baroque art. The first uses of the term 'baroque' for music were criticisms. In an anonymous, satirical review of the première in October 1733 of Rameau's Hippolyte et Aricie, printed in the Mercure de France in May 1734, the critic implied that the novelty in this opera was "du barocque," complaining that the music lacked coherent melody, was filled with unremitting dissonances, constantly changed key and meter, and speedily ran through every compositional device.[40]Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was a musician and noted composer as well as philosopher, made a very similar observation in 1768 in the famous Encylopedié of Denis Diderot: "Baroque music is that in which the harmony is confused, and loaded with modulations and dissonances. The singing is harsh and unnatural, the intonation difficult, and the movement limited. It appears that term comes from the word 'baroco' used by logicians."[7]

Common use of the term for the music of the period began only in 1919, by Curt Sachs,[41] and it was not until 1940 that it was first used in English in an article published by Manfred Bukofzer.[40]

The baroque was a period of musical experimentation and innovation. New forms were invented, including the concerto and sinfonia. Opera was born in Italy at the end of the 16th century (with Jacopo Peri's mostly lost Dafne, produced in Florence in 1598) and soon spread through the rest of Europe: Louis XIV created the first Royal Academy of Music, In 1669, the poet Pierre Perrin opened an academy of opera in Paris, the first opera theater in France open to the public, and premiered Pomone, the first grand opera in French, with music by Robert Cambert, with five acts, elaborate stage machinery, and a ballet.[42]Heinrich Schütz in Germany, Jean-Baptiste Lully in France, and Henry Purcell in England all helped to establish their national traditions in the 17th century.

The classical ballet also originated in the Baroque era. The style of court dance was brought to France by Marie de Medici, and in the beginning the members of the court themselves were the dancers. Louis XIV himself performed in public in several ballets. In March 1662, the Académie Royale de Danse, was founded by the King. It was the first professional dance school and company, and set the standards and vocabulary for ballet throughout Europe during the period.[42]

Several new instruments, including the piano, were introduced during this period. The invention of the piano is credited to Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) of Padua, Italy, who was employed by Ferdinando de' Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany, as the Keeper of the Instruments. .[43][44] Cristofori named the instrument un cimbalo di cipresso di piano e forte ("a keyboard of cypress with soft and loud"), abbreviated over time as pianoforte, fortepiano, and later, simply, piano.[45]

Composers and examples

Giovanni Gabrieli (c. 1554/1557–1612) Sonata pian' e forte (1597), In Ecclesiis (from Symphoniae sacrae book 2, 1615)

Giovanni Girolamo Kapsperger (c. 1580–1651) Libro primo di villanelle, 20 (1610)

Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), L'Orfeo, favola in musica (1610)

Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672), Musikalische Exequien (1629, 1647, 1650)

Francesco Cavalli (1602–1676), L'Egisto (1643), Ercole amante (1662), Scipione affricano (1664)

Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–1687), Armide (1686)

Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704), Te Deum (1688–1698)

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber (1644–1704), Mystery Sonatas (1681)

John Blow (1649–1708), Venus and Adonis (1680–1687)

Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706), Canon in D (1680)

Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713), 12 concerti grossi, Op. 6 (1714)

Marin Marais (1656–1728), Sonnerie de Ste-Geneviève du Mont-de-Paris (1723)

Henry Purcell (1659–1695), Dido and Aeneas (1688)

Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725), L'honestà negli amori (1680), Il Pompeo (1683), Mitridate Eupatore (1707)

François Couperin (1668–1733), Les barricades mystérieuses (1717)

Tomaso Albinoni (1671–1751), Didone abbandonata (1724)

Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741), The Four Seasons (1725)

Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679–1745), Il Serpente di Bronzo (1730), Missa Sanctissimae Trinitatis (1736)

Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), Der Tag des Gerichts (1762)

Johann David Heinichen (1683–1729)

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764), Dardanus (1739)

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), Water Music (1717), Messiah (1741)

Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757), Sonatas for harpsichord

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), Toccata and Fugue in D minor (1703–1707), Brandenburg Concertos (1721), St Matthew Passion (1727)

Nicola Porpora (1686–1768), Semiramide riconosciuta (1729)

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710–1736), Stabat Mater (1736)

Theatre

Set design for Andromedé by Pierre Corneille, (1650)

The Baroque period was a golden age for theater in France and Spain; playwrights included Corneille, Racine and Moliere in France; and Lope de Vega and Pedro Calderón de la Barca Spain.

During the Baroque period, the art and style of the theater evolved rapidly, alongside the development of opera and of ballet. The design of newer and larger theaters, the invention the use of more elaborate machinery, the wider use of the proscenium arch, which framed the stage and hid the machinery from the audience, encouraged more scenic effects and spectacle.[46]

The Baroque had a Catholic and conservative character in Spain, following an Italian literary models during the Renaissance.[47] The Hispanic Baroque theatre aimed for a public content with an ideal reality that manifested fundamental three sentiments: Catholic religion, monarchist and national pride and honour originating from the chivalric, knightly world.[48]

Two periods are known in the Baroque Spanish theatre, with the division occurring in 1630. The first period is represented chiefly by Lope de Vega, but also by Tirso de Molina, Gaspar Aguilar, Guillén de Castro, Antonio Mira de Amescua, Luis Vélez de Guevara, Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, Diego Jiménez de Enciso, Luis Belmonte Bermúdez, Felipe Godínez, Luis Quiñones de Benavente or Juan Pérez de Montalbán. The second period is represented by Pedro Calderón de la Barca and fellow dramatists Antonio Hurtado de Mendoza, Álvaro Cubillo de Aragón, Jerónimo de Cáncer, Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla, Juan de Matos Fragoso, Antonio Coello y Ochoa, Agustín Moreto, and Francisco Bances Candamo.[49] These classifications are loose because each author had his own way and could occasionally adhere himself to the formula established by Lope. It may even be that the "manner" of Lope was more liberal and structured than Calderón's.[50]

Lope de Vega introduced through his Arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo (1609) the new comedy. He established a new dramatic formula that broke the three Aristotle unities of the Italian school of poetry (action, time and place) and a fourth unity of Aristotle which is about style, mixing of tragic and comic elements showing different types of verses and stanzas upon what is represented.[51] Although Lope has a great knowledge of the plastic arts, he did not use it during the major part of his career nor in theatre or scenography. The Lope's comedy granted a second role to the visual aspects of the theatrical representation.[52]

Tirso de Molina, Lope de Vega, and Calderón were the most important play writers in Golden Era Spain. Their works, known for their subtle intelligence and profound comprehension of a person's humanity, could be considered a bridge between Lope's primitive comedy and the more elaborate comedy of Calderón. Tirso de Molina is best known for two works, The Convicted Suspicions and The Trickster of Seville, one of the first versions of the Don Juan myth.[53]

Upon his arrival to Madrid, Cosimo Lotti brought to the Spanish court the most advanced theatrical techniques of Europe. His techniques and mechanic knowledge were applied in palace exhibitions called "Fiestas" and in lavish exhibitions of rivers or artificial fountains called "Naumaquias". He was in charge of styling the Gardens of Buen Retiro, of Zarzuela and of Aranjuez and the construction of the theatrical building of Coliseo del Buen Retiro.[54] Lope's formulas begins with a verse that it unbefitting of the palace theatre foundation and the birth of new concepts that begun the careers of some play writers like Calderón de la Barca. Marking the principal innovations of the New Lopesian Comedy, Calderón's style marked many differences, with a great deal of constructive care and attention to his internal structure. Calderón's work is in formal perfection and a very lyric and symbolic language. Liberty, vitality and openness of Lope gave a step to Calderón's intellectual reflection and formal precision. In his comedy it reflected his ideological and doctrine intentions in above the passion and the action, the work of Autos sacramentales achieved high ranks.[55] The genre of Comedia is political, multi-artistic and in a sense hybrid. The poetic text interweaved with Medias and resources originating from architecture, music and painting freeing the deception that is in the Lopesian comedy was made up from the lack of scenery and engaging the dialogue of action.[56]

The best known German playwright was Andreas Gryphius, who used the Jesuit model of the Dutch Joost van den Vondel and Pierre Corneille. There was also Johannes Velten who combined the traditions of the English comedians and the commedia del'arte with the classic theatre of Corneille and Molière. His touring company was perhaps the most significant and important of the 17th century.

End of the style, condemnation and academic rediscovery

Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV, probably without intending it, contributed to the decline of the baroque and rococo style. In 1750 she sent her nephew, Abel-François Poisson de Vandières, on a two-year mission to study artistic and archeological developments in Italy. He was accompanied by several artists, including the engraver Nicolas Cochin and the architect Soufflot. They returned to Paris with a passion for classical art. Vandiéres became the Marquis of Marigny, and was named Royal Director of buildings in 1754. He turned official French architecture toward the neoclassical. Cochin became an important art critic; he denounced the petit style of Boucher, and called for a grand style with a new emphasis on antiquity and nobility in the academies of painting of architecture. [57]

The pioneer German art historian and archeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann also condemned the baroque style, and praised the superior values of classical art and architecture. By the 19th century, Baroque was a target for ridicule and criticism. The neoclassical critic Francesco Milizia wrote: "Borrominini in architecture, Bernini in sculpture, Pierre de Cortone in painting...are a plague on good taste, which infected a large number of artists."[58] In the 19th century, criticism went even further; the British critic John Ruskin declared that baroque sculpture was not only bad, but also morally corrupt.[59]

The Swiss-born art historian Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945) started the rehabilitation of the word Baroque in his Renaissance und Barock (1888); Wölfflin identified the Baroque as "movement imported into mass", an art antithetic to Renaissance art. He did not make the distinctions between Mannerism and Baroque that modern writers do, and he ignored the later phase, the academic Baroque that lasted into the 18th century. Baroque art and architecture became fashionable between the two World Wars, and has largely remained in critical favor. The term "Baroque" may still be used, usually pejoratively, describing works of art, craft, or design that are thought to have excessive ornamentation or complexity of line.

Italian Baroque

Facade of the Church of the Gesù, Rome (1584)

Saint Ignatius, Rome (1626–1650)

Ceiling of the Church of the Gesù, Rome (1674–1679)

The Ca Rezzonico, Venice (1649–1656)

Cartouches decorating courtyard of the Palazzo Spada in Rome by Borromini (1632)

Gallery with forced perspective by Francesco Borromini, creates the illusion that the corridor is much longer than it really is. Palazzo Spada (1632)

Interior plan of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1646)

Interior Cupola of the Chapel of the Holy Shroud, Turin (1668–94)

Basilica of Superga, Turin (1717–1731)

Spanish Baroque

Dome of Royal Chapel, Palacio Real, Madrid (1738–1755)

Retable of Convento de San Esteban, Salamanca (1690)

El Transparente Altarpiece, Toledo Cathedral, (1729–1732)

Hospice of San Fernando, Madrid (1750)

Plaza Mayor, Salamanca (1729)

Granada Cathedral (1652–1657)

Jesuit College, Tepoztlán, Mexico

Baroque and Rococo in Germany, Austria and Central Europe

Quadratura of the Jesuitkirche, Vienna

Late Baroque or Rococo: High altar of Basilika Vierzehnheiligen in Bavaria (1743–1772)

Sanssouci, in Potsdam by Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff (1745–1747)

Plan of the Basilika Vierzehnheiligen (1743–1772)

The Wieskirche by Dominikus Zimmermann, Bavaria, (1728–1733)

Ceiling of Ottobeuren Abbey in Bavaria (1711–1725)

The Vierzehnheigen Basilica, Bavaria by Balthasar Neumann (1743–1772)

Remnant of Zwinger Palace in Dresden (1710–1728)

Style Louis XIV

Vaux-le-Vicomte (1657–1661)

East facade of the Louvre by Claude Perrault and Louis Le Vau (1668–1680)

Hall of Mirrors in Versailles (1678–1686)

See also

- Baroque architecture

- List of Baroque architecture

- Baroque in Brazil

- Czech Baroque architecture

- Dutch Baroque architecture

- Earthquake Baroque

- English Baroque

- French Baroque architecture

- Italian Baroque

- Lutheran Baroque art

- Sicilian Baroque

- New Spanish Baroque

- Neoclassicism (music)

- Andean Baroque

- Baroque in Poland

- Baroque architecture in Portugal

- Naryshkin Baroque

- Petrine Baroque

- Siberian Baroque

- Spanish Baroque

- Ukrainian Baroque

Notes

^ ab Heal, Bridget (1 December 2011). "'Better Papist than Calvinist': Art and Identity in Later Lutheran Germany". German History. German History Society. 29 (4)..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ http://dle.rae.es/srv/search?m=30&w=barroco

^ Oxford English Dictionary on-line definition of Baroque

^ Michael Meere, French Renaissance and Baroque Drama: Text, Performance, Theory, Rowman & Littlefield, 2015,

ISBN 1611495490

^ Antoine Arnauld, Pierre Nicole, La logique ou l'art de penser, Part Three, chapter VI (in French)

^ Claude V. Palisca, "Baroque". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

^ ab Encyclopedie; Lettre sur la Musique Francaise under the direction of Denis Diderot

^ Hopkins, Owen, "Les Styles en Architecture, (2014), p. 70

^ Panofsky, Erwin (1995). "What is Baroque?". Three Essays on Style. The MIT Press. p. 19.

^ Hopkins, Owen, Les Styles en Architecture (2014), p. 70

^ Hughes, J. Quentin (1953). The Influence of Italian Mannerism Upon Maltese Architecture. Melitensiawath. Retrieved 8 July 2016. pp. 104–110.

^ Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya, Gardner's Art Through the Ages (Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2005), p. 516.

^ Heal, Bridget (20 February 2018). "The Reformation and Lutheran baroque". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 May 2018.However, the writings of theologians can go only so far towards explaining the evolution of confessional consciousness and the shaping of religious identity. Lutheran attachment to religious images was a result not only of Luther’s own cautious endorsement of their use, but also of the particular religious and political context in which his Reformation unfolded. After the reformer’s death in 1546, the image question was fiercely contested once again. But as Calvinism, with its iconoclastic tendencies, spread, Germany’s Lutherans responded by reaffirming their commitment to the proper use of religious images. In 1615, Berlin’s Lutheran citizens even rioted when their Calvinist rulers removed images from the city’s Cathedral.

^ Ducher, pg. 102

^ ab Ducher (1988) p. 106-107

^ Ducher (1988), pg. 102

^ Cabanne (1988) page 12

^ Ducher (1988)

^ ab Ducher (1988) p. 104.

^ Cabanne (1988) page 15

^ Cabanne (1988), pages 18–19.

^ Cabanne (1988) page 48-49

^ abc Cabanne (1988) pgs. 48–51

^ Cabanne (1988) pg. 63

^ Ducher, Robert, La Caractéristique des Styles (2014), page 92

^ Cabanne (1988), pp. 89–94.

^ Ducher (1988) pp. 104–105.

^ Cabanne (1988) pages 25–32.

^ Cabanne (1988), pgs. 25–28.

^ Cabanne (1988), pgs. 28–33.

^ * William Craft Brumfield. A History of Russian Architecture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993)

ISBN 978-0-521-40333-7 (Chapter Eight: "The Foundations of the Baroque in Saint Petersburg")

^ Prater and Bauer, La Peinture du baroque (1997), pg. 11

^ Prater and Bauer, La Peinture du baroque (1997), pgs. 3–15

^ Prater and Bauer, La Peinture du baroque (1997), pg. 12

^ Ducher, Robert, La Caractéistique des Styles (2014), pg. 92

^ Ducher (1988) pages 108–109

^ Cabanne (1988) pp. 102–104

^ Boucher, La Sculpture baroque italienne (1999), p. 146

^ Boucher (1999) page 16.

^ ab Palisca 2001.

^ Sachs, Curt (1919). Barockmusik [Baroque Music]. Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters (in German). 26. Leipzig: Edition Peters. pp. 7–15.

^ ab Bély, Lucien, Louis XIV- Le Plus Grand Roi du Monde (2005), pp. 152–54

^ Erlich, Cyril (1990). The Piano: A History. Oxford University Press, USA; Revised edition. ISBN 0-19-816171-9.

^ Powers, Wendy (2003). "The Piano: The Pianofortes of Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

^ Isacoff (2012, 23)

^ Britannica on-line, Baroque Theater

^ González Mas, Ezequiel (1980). Historia de la literatura española: (Siglo XVII). Barroco, Volumen 3. La Editorial, UPR, pp. 1–2

^ González Mas, Ezequiel (1980). Historia de la literatura española: (Siglo XVII). Barroco, Volumen 3. La Editorial, UPR, p. 8.

^ González Mas, Ezequiel (1980). Historia de la literatura española: (Siglo XVII). Barroco, Volumen 3. La Editorial, UPR, p. 13

^ González Mas, Ezequiel (1980). Historia de la literatura española: (Siglo XVII). Barroco, Volumen 3. La Editorial, UPR, p. 91

^ Lope de Vega, 2010, Comedias: El Remedio en la Desdicha. El Mejor Alcalde El Rey, pp. 446–447

^ Amadei-Pulice, 1990, María Alicia (1990). Calderón y el barroco: exaltación y engaño de los sentidos. John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 6

^ Wilson, Edward M.; Moir, Duncan (1992). Historia de la literatura española: Siglo De Oro: Teatro (1492–1700). Editorial Ariel, pp. 155–158

^ Amadei-Pulice, 1990, María Alicia (1990). Calderón y el barroco: exaltación y engaño de los sentidos. John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 26–27

^ Molina Jiménez, María Belén (2008). El teatro musical de Calderón de la Barca: Análisis textual. EDITUM, p. 56

^ Amadei-Pulice, 1990, María Alicia (1990). Calderón y el barroco: exaltación y engaño de los sentidos. John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 6–9

^ Cabanne, 1988 & pg. 106.

^ Boucher, Bruce, La Sculpture baroque italienne, Thames and Hudson, (1997), page 9

^ Boucher (1998) page 9.

Books cited in text

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

- Bély, Lucien, Louis XIV- Le plus grand roos du monde, (2005), (in French) Editions Jean-Paul Gisserot

- Boucher, Bruce, Italian Baroque Sculpture, (1998), Thames & Hudson (World of Art),

ISBN 0500203075 - Cabanne, Pierre, L'Art Classique et le Baroque (1988), (in French), Larousse, Paris

ISBN 978-2-03-583324-2 - Causa, Raffaello, L'Art au XVIII siècle du rococo à Goya (1963), (in French) Hachcette, Paris

ISBN 2-86535-036-3

Ducher, Robert. 1988. Caractéristique des Styles. Paris: Flammarion.

ISBN 2-08-011539-1- Gardner, Helen, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. 2005. Gardner's Art Through the Ages, 12th edition. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

ISBN 978-0-15-505090-7 (hardcover)

Isacoff, Stuart (2012). A Natural History of the Piano: The Instrument, the Music, the Musicians – From Mozart to Modern Jazz and Everything in Between. Knopf Doubleday Publishing.- Prater, Andreas, and Bauer, Hermann, La Peinture du baroque (1997), (in French), Taschen, Paris

ISBN 3-8228-8365-4 - Tazartes, Maurizia, Fontaines de Rome, (2004), (in French) Citadelles, Paris

ISBN 2-85088-200-3

Further reading

- Andersen, Liselotte. 1969. "Baroque and Rococo Art", New York: H. N. Abrams.

Bailey, Gauvin Alexander, 2012. Baroque & Rococo, London, Phaidon Press.[1]

Bazin, Germain, 1964. Baroque and Rococo. Praeger World of Art Series. New York: Praeger. (Originally published in French, as Classique, baroque et rococo. Paris: Larousse. English edition reprinted as Baroque and Rococo Art, New York: Praeger, 1974)

Buci-Glucksmann, Christine. 1994. Baroque Reason: The Aesthetics of Modernity. Sage.- Downes, Kerry, "Baroque", Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, Web. 23 Oct. 2017, subscription required

- Hills, Helen (ed.). 2011. Rethinking the Baroque. Farnham, Surrey; Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

ISBN 978-0-7546-6685-1. - Hortolà, Policarp, 2013, The Aesthetics of Haemotaphonomy. Sant Vicent del Raspeig: ECU.

ISBN 978-84-9948-991-9.

Kitson, Michael. 1966. The Age of Baroque. Landmarks of the World's Art. London: Hamlyn; New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lambert, Gregg, 2004. Return of the Baroque in Modern Culture. Continuum.

ISBN 978-0-8264-6648-8.

Martin, John Rupert. 1977. Baroque. Icon Editions. New York: Harper and Rowe.

ISBN 0-06-435332-X (cloth);

ISBN 0-06-430077-3 (pbk.)

Palisca, Claude V. (1991) [1961]. Baroque Music. Prentice Hall History of Music (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-058496-7. OCLC 318382784.

Wölfflin, Heinrich. 1964. Renaissance and Baroque (Reprinted 1984; originally published in German, 1888) The classic study.

ISBN 0-8014-9046-4

Vuillemin, Jean-Claude, 2013. Episteme baroque: le mot et la chose. Hermann.

ISBN 978-2-7056-8448-8.- Wakefield, Steve. 2004. Carpentier's Baroque Fiction: Returning Medusa's Gaze. Colección Támesis. Serie A, Monografías 208. Rochester, NY: Tamesis.

ISBN 1-85566-107-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baroque art. |

"Baroque". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Baroque". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). 1911.- The baroque and rococo culture

- Webmuseum Paris

- barocke in Val di Noto – Sizilien

- Baroque in the "History of Art"

- The Baroque style and Luis XIV influence

- Melvyn Bragg's BBC Radio 4 program In Our Time: The Baroque

"Baroque Style Guide". British Galleries. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2007.