Barbados

Barbados

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Coordinates: 13°10′N 59°33′W / 13.167°N 59.550°W / 13.167; -59.550

Barbados | |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Motto: "Pride and Industry" | |

Anthem: In Plenty and In Time of Need Royal anthem: God Save the Queen | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Bridgetown 13°06′N 59°37′W / 13.100°N 59.617°W / 13.100; -59.617 |

| Official languages | English |

| Recognised regional languages | Bajan Creole |

Ethnic groups (est. 2010[1]) |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

• Governor-General | Dame Sandra Mason |

• Prime Minister | Mia Mottley |

| Legislature | Parliament |

• Upper house | Senate |

• Lower house | House of Assembly |

| Independence | |

• From the United Kingdom | 30 November 1966 |

| Area | |

• Total | 439 km2 (169 sq mi) (183rd) |

• Water (%) | Negligible |

| Population | |

• 2010 census | 277,821[2] (181st) |

• Density | 660/km2 (1,709.4/sq mi) (15th) |

GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $4.663 billion[3] |

• Per capita | $16,669[3] (73rd) |

GDP (nominal) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $4.385 billion[3] |

• Per capita | $15,677[3] |

HDI (2017) | very high · 58th |

| Currency | Barbadian dollar ($) (BBD) |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (Eastern Caribbean) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Not observed) |

| Driving side | left[5] |

| Calling code | +1 -246 |

| ISO 3166 code | BB |

| Internet TLD | .bb |

Barbados (/bɑːrˈbeɪdɒs/ (![]() listen) or /-doʊs/) is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of North America. It is 34 kilometres (21 miles) in length and up to 23 km (14 mi) in width, covering an area of 432 km2 (167 sq mi). It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 km (62 mi) east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea;[6] therein, Barbados is east of the Windwards, part of the Lesser Antilles, roughly at 13°N of the equator. It is about 168 km (104 mi) east of both the countries of Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and 400 km (250 mi) north-east of Trinidad and Tobago. Barbados is outside the principal Atlantic hurricane belt. Its capital and largest city is Bridgetown.

listen) or /-doʊs/) is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of North America. It is 34 kilometres (21 miles) in length and up to 23 km (14 mi) in width, covering an area of 432 km2 (167 sq mi). It is situated in the western area of the North Atlantic and 100 km (62 mi) east of the Windward Islands and the Caribbean Sea;[6] therein, Barbados is east of the Windwards, part of the Lesser Antilles, roughly at 13°N of the equator. It is about 168 km (104 mi) east of both the countries of Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and 400 km (250 mi) north-east of Trinidad and Tobago. Barbados is outside the principal Atlantic hurricane belt. Its capital and largest city is Bridgetown.

Inhabited by Kalinago people since the 13th century, and prior to that by other Amerindians, Barbados was visited by Spanish navigators in the late 15th century and claimed for the Spanish Crown. It first appeared in a Spanish map in 1511.[7][8] The Portuguese visited the island in 1536, but they left it unclaimed, with their only remnants being an introduction of wild hogs for a good supply of meat whenever the island was visited. An English ship, the Olive Blossom, arrived in Barbados in 1625; its men took possession of it in the name of King James I. In 1627, the first permanent settlers arrived from England, and it became an English and later British colony.[9] As a wealthy sugar colony, it became an English centre of the African slave trade until that trade was outlawed in 1807, with final emancipation of slaves in Barbados occurring over a period of years from 1833.

On 30 November 1966, Barbados became an independent state and Commonwealth realm with the British monarch (currently Queen Elizabeth II) as hereditary head of state.[10] It has a population of 284,996[11] people, predominantly of African descent. Despite being classified as an Atlantic island, Barbados is considered to be a part of the Caribbean, where it is ranked as a leading tourist destination, and the most visited destination in the Caribbean. Forty percent of the tourists come from the UK, with the US and Canada making up the next large groups of visitors to the island.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 1627–1639

2.1.1 Early English settlement

2.2 1640–1790

2.2.1 England's civil war

2.2.2 Sugar cane

3 Geography and climate

3.1 Geology

3.2 Climate

3.3 Environmental issues

3.4 Wildlife

4 Demographics

4.1 Ethnic groups

4.2 Languages

4.3 Religion

5 Government and politics

5.1 Political culture

5.2 Foreign relations

5.2.1 World Trade Organization, European Commission, CARIFORUM

5.2.2 The Double Taxation Relief (CARICOM) Treaty 1994

5.2.3 European Nations

5.3 Military

5.4 Administrative divisions

5.5 Human rights

6 Economy

7 Health

8 Education

8.1 Educational testing

9 Culture

9.1 Cuisine

9.2 Music

9.3 Public holidays

10 Tourism

11 Sports

12 Transport

13 Notable people

14 See also

15 References

16 Further reading

16.1 Videography

17 External links

Etymology[edit]

The name "Barbados" is from either the Portuguese term Os Barbados or the Spanish equivalent, Los Barbados, both meaning "the bearded ones". It is unclear whether "bearded" refers to the long, hanging roots of the bearded fig-tree (Ficus citrifolia), indigenous to the island, or to the allegedly bearded Caribs who once inhabited the island, or, more fancifully, to a visual impression of a beard formed by the sea foam that sprays over the outlying reefs. In 1519, a map produced by the Genoese mapmaker Visconte Maggiolo showed and named Barbados in its correct position. Furthermore, the island of Barbuda in the Leewards is very similar in name and was once named "Las Barbudas" by the Spanish.

It is uncertain which European nation arrived first in Barbados. One lesser-known source points to earlier revealed works predating contemporary sources indicating it could have been the Spanish.[7] Many if not most believe the Portuguese, en route to Brazil,[12][13] were the first Europeans to come upon the island.

The original name for Barbados in the Pre-Columbian era was Ichirouganaim, according to accounts by descendants of the indigenous Arawakan-speaking tribes in other regional areas, with possible translations including "Red land with white teeth"[14] or "Redstone island with teeth outside (reefs)"[15] or simply "Teeth".[16][17][18]

Colloquially, Barbadians refer to their home island as "Bim" or other nicknames associated with Barbados, including "Bimshire". The origin is uncertain, but several theories exist. The National Cultural Foundation of Barbados says that "Bim" was a word commonly used by slaves, and that it derives from the Igbo term bém from bé mụ́ meaning 'my home, kindred, kind',[19] the Igbo phoneme /e/ in the Igbo orthography is very close to [ɪ].[20] The name could have arisen due to the relatively large percentage of enslaved Igbo people from modern-day southeastern Nigeria arriving in Barbados in the 18th century.[21][22]

The words 'Bim' and 'Bimshire' are recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary and Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionaries. Another possible source for 'Bim' is reported to be in the Agricultural Reporter of 25 April 1868, where the Rev. N. Greenidge (father of one of the island's most famous scholars, Abel Hendy Jones Greenidge) suggested the listing of Bimshire as a county of England. Expressly named were "Wiltshire, Hampshire, Berkshire and Bimshire".[19] Lastly, in the Daily Argosy (of Demerara, i.e. Guyana) of 1652, there is a reference to Bim as a possible corruption of 'Byam', the name of a Royalist leader against the Parliamentarians. That source suggested the followers of Byam became known as 'Bims' and that this became a word for all Barbadians.[19]

History[edit]

Reproduction of the Blue Ensign flag of the Colony of Barbados, used from 1870 to 1966.

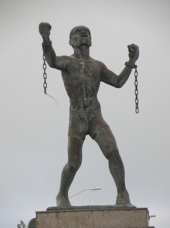

Statue of Bussa, Bridgetown. Bussa led the largest slave rebellion in Barbadian history.

Amerindian settlement of Barbados dates to about the 4th to 7th centuries AD, by a group known as the Saladoid-Barrancoid.[23] The Arawaks from South America became dominant around 800 AD, and maintained that status until around 1200. In the 13th century, the Kalinago (Island Caribs) arrived from South America.

The Spanish and Portuguese briefly claimed Barbados from the late 16th to the 17th centuries. The Arawaks are believed to have fled to neighbouring islands. Apart from possibly displacing the Caribs, the Spanish and Portuguese made little impact and left the island uninhabited. Some Arawaks migrated from British Guiana (modern-day Guyana) in the 19th century and continue to live in Barbados.[24][25]

In the very early years (1620–1640s) the majority of the labour was provided by European indentured servants, mainly English, Irish and Scottish, with enslaved Africans and enslaved Amerindian providing little of the workforce. During the Cromwellian era (1650s) this included a large number of prisoners-of-war, vagrants and people who were illicitly kidnapped, who were forcibly transported to the island and sold as servants. These last two groups were predominately Irish, as several thousand were infamously rounded up by English merchants and sold into servitude in Barbados and other Caribbean islands during this period.[26] Cultivation of tobacco, cotton, ginger and indigo was thus handled primarily by European indentured labour until the start of the sugar cane industry in the 1640s and the growing reliance and importation of enslaved Africans. From its English settlement and as Barbados's economy grew, Barbados maintained a relatively large measure of local autonomy first as a proprietary colony and later a crown colony. The House of Assembly began meeting in 1639. Among the island's earliest leading figures was the Anglo-Dutch Sir William Courten.

The 1780 hurricane killed over 4,000 people on Barbados. In 1854, a cholera epidemic killed over 20,000 inhabitants.[27] At emancipation in 1833, the size of the slave population was approximately 83,000. Between 1946 and 1980, Barbados's rate of population growth was diminished by one-third because of emigration to Britain.[28]

1627–1639[edit]

Early English settlement[edit]

The settlement was established as a proprietary colony and funded by Sir William Courten, a City of London merchant who acquired the title to Barbados and several other islands. So the first colonists were actually tenants and much of the profits of their labour returned to Courten and his company.[29]

The first English ship, which had arrived on 14 May 1625, was captained by John Powell. The first settlement began on 17 February 1627, near what is now Holetown (formerly Jamestown),[30] by a group led by John Powell's younger brother, Henry, consisting of 80 settlers and 10 English labourers. The latter were young indentured labourers who according to some sources had been abducted, effectively making them slaves.[31]

Courten's title was transferred to James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle, in what was called the "Great Barbados Robbery." Carlisle then chose as governor Henry Hawley, who established the House of Assembly in 1639, in an effort to appease the planters, who might otherwise have opposed his controversial appointment.

In the period 1640–60, the West Indies attracted over two-thirds of the total number of English emigrants to the Americas. By 1650 there were 44,000 settlers in the West Indies, as compared to 12,000 on the Chesapeake and 23,000 in New England. Most English arrivals were indentured. After five years of labour, they were given "freedom dues" of about ₤10, usually in goods. (Before the mid-1630s, they also received 5 to 10 acres of land, but after that time the island filled and there was no more free land.) Around the time of Cromwell a number of rebels and criminals were also transported there. Timothy Meads of Warwickshire was one of the rebels sent to Barbados at that time, before he received compensation for servitude of 1000 acres of land in North Carolina in 1666. Parish registers from the 1650s show, for the white population, four times as many deaths as marriages. The death rate was very high.

Before this, the mainstay of the infant colony's economy was the growth export of tobacco, but tobacco prices eventually fell in the 1630s, as Chesapeake production expanded.

1640–1790[edit]

England's civil war[edit]

Around the same time, fighting during the War of the Three Kingdoms and the Interregnum spilled over into Barbados and Barbadian territorial waters. The island was not involved in the war until after the execution of Charles I, when the island's government fell under the control of Royalists (ironically the Governor, Philip Bell, remaining loyal to Parliament while the Barbadian House of Assembly, under the influence of Humphrey Walrond, supported Charles II). To try to bring the recalcitrant colony to heel, the Commonwealth Parliament passed an act on 3 October 1650 prohibiting trade between England and Barbados, and because the island also traded with the Netherlands, further navigation acts were passed prohibiting any but English vessels trading with Dutch colonies. These acts were a precursor to the First Anglo-Dutch War. The Commonwealth of England sent an invasion force under the command of Sir George Ayscue, which arrived in October 1651. After some skirmishing, the Royalists in the House of Assembly led by Lord Willoughby surrendered. The conditions of the surrender were incorporated into the Charter of Barbados (Treaty of Oistins), which was signed at the Mermaid's Inn, Oistins, on 17 January 1652.[32]

Sugar cane[edit]

George Washington House was visited by George Washington in 1751, in what is believed to have been his only trip outside the present day United States.[33]

The introduction of sugar cane from Dutch Brazil in 1640 completely transformed society and the economy. Barbados eventually had one of the world's biggest sugar industries.[34] One group instrumental in ensuring the early success of the industry were the Sephardic Jews, who had originally been expelled from the Iberian peninsula, to end up in Dutch Brazil.[34] As the effects of the new crop increased, so did the shift in the ethnic composition of Barbados and surrounding islands. The workable sugar plantation required a large investment and a great deal of heavy labour. At first, Dutch traders supplied the equipment, financing, and enslaved Africans, in addition to transporting most of the sugar to Europe. In 1644 the population of Barbados was estimated at 30,000, of which about 800 were of African descent, with the remainder mainly of English descent. These English smallholders were eventually bought out and the island filled up with large sugar plantations worked by enslaved Africans. By 1660 there was near parity with 27,000 blacks and 26,000 whites. By 1666 at least 12,000 white smallholders had been bought out, died, or left the island. Many of the remaining whites were increasingly poor. By 1680 there were 17 slaves for every indentured servant. By 1700, there were 15,000 free whites and 50,000 enslaved Africans.

Due to the increased implementation of slave codes, which created differential treatment between Africans and the white workers and ruling planter class, the island became increasingly unattractive to poor whites. Black or slave codes were implemented in 1661, 1676, 1682, and 1688. In response to these codes, several slave rebellions were attempted or planned during this time, but none succeeded. Nevertheless, poor whites who had or acquired the means to emigrate often did so. Planters expanded their importation of enslaved Africans to cultivate sugar cane. One early advocate of slave rights in Barbados was the visiting Quaker preacher Alice Curwen in 1677: "For I am perswaded, that if they whom thou call'st thy Slaves, be Upright-hearted to God, the Lord God Almighty will set them Free in a way that thou knowest not; for there is none set free but in Christ Jesus, for all other Freedom will prove but a Bondage."[35]

Geography and climate[edit]

A map of Barbados

Barbados is situated in the Atlantic Ocean, east of the other West Indies Islands. Barbados is the easternmost island in the Lesser Antilles. It is flat in comparison to its island neighbours to the west, the Windward Islands. The island rises gently to the central highland region, with the high point of the nation being Mount Hillaby in the geological Scotland District 340 m (1,120 ft) above sea level.

In the parish of Saint Michael lies Barbados's capital and main city, Bridgetown. Other major towns scattered across the island include Holetown, in the parish of Saint James; Oistins, in the parish of Christ Church; and Speightstown, in the parish of Saint Peter.

Geology[edit]

Barbados lies on the boundary of the South American and the Caribbean Plates.[36] The subduction of the South American plate beneath the Caribbean plate scrapes sediment from the South American plate and deposits it above the subduction zone forming an accretionary prism. The rate of this depositing of material allows Barbados to rise at a rate of about 25 mm (1 in) per 1,000 years.[37] This subduction means geologically the island is composed of coral roughly 90 m (300 ft) thick, where reefs formed above the sediment. The land slopes in a series of "terraces" in the west and goes into an incline in the east. A large proportion of the island is circled by coral reefs.

The erosion of limestone in the northeast of the island, in the Scotland District, has resulted in the formation of various caves and gullies. On the Atlantic east coast of the island coastal landforms, including stacks, have been created due to the limestone composition of the area. Also notable in the island is the rocky cape known as Pico Teneriffe[38] or Pico de Tenerife, which is named after the fact that the island of Tenerife in Spain is the first land east of Barbados according to the belief of the locals.

Climate[edit]

Bathsheba, Saint Joseph

The country generally experiences two seasons, one of which includes noticeably higher rainfall. Known as the "wet season", this period runs from June to November. By contrast, the "dry season" runs from December to May. Annual precipitation ranges between 1,000 and 2,300 mm (40 and 90 in).

From December to May the average temperatures range from 21 to 31 °C (70 to 88 °F), while between June and November, they range from 23 to 31 °C (73 to 88 °F).[39]

On the Köppen climate classification scale, much of Barbados is regarded as a tropical monsoon climate (Am). However, breezes of 12 to 16 km/h (7 to 10 mph) abound throughout the year and give Barbados a climate which is moderately tropical.

Infrequent natural hazards include earthquakes, landslips, and hurricanes. Barbados is often spared the worst effects of the region's tropical storms and hurricanes during the rainy season. Its location in the south-east of the Caribbean region puts the country just outside the principal hurricane strike zone. On average, a major hurricane strikes about once every 26 years. The last significant hit from a hurricane to cause severe damage to Barbados was Hurricane Janet in 1955; in 2010 the island was struck by Hurricane Tomas, but this caused only minor damage across the country.[40]

Environmental issues[edit]

Barbados, seen from the International Space Station.

Barbados is susceptible to environmental pressures. As one of the world's most densely populated isles, the government worked during the 1990s[41] to aggressively integrate the growing south coast of the island into the Bridgetown Sewage Treatment Plant to reduce contamination of offshore coral reefs.[42][43] As of the first decade of the 21st century, a second treatment plant has been proposed along the island's west coast. Being so densely populated, Barbados has made great efforts to protect its underground aquifers.[44]

As a coral-limestone island, Barbados is highly permeable to seepage of surface water into the earth. The government has placed great emphasis on protecting the catchment areas that lead directly into the huge network of underground aquifers and streams.[44] On occasion illegal squatters have breached these areas, and the government has removed squatters to preserve the cleanliness of the underground springs which provide the island's drinking water.[45]

The government has placed a huge emphasis on keeping Barbados clean with the aim of protecting the environment and preserving offshore coral reefs which surround the island. Many initiatives to mitigate human pressures on the coastal regions of Barbados and seas come from the Coastal Zone Management Unit (CZMU).[46][47] Barbados has nearly 90 kilometres (56 miles) of coral reefs just offshore and two protected marine parks have been established off the west coast.[48] Overfishing is another threat which faces Barbados.[49]

Although on the opposite side of the Atlantic, and some 4,800 kilometres (3,000 miles) west of Africa, Barbados is one of many places in the American continent that experience heightened levels of mineral dust from the Sahara Desert.[50] Some particularly intense dust episodes have been blamed partly for the impacts on the health of coral reefs[51] surrounding Barbados or asthmatic episodes,[52] but evidence has not wholly supported the former such claim.[53]

Wildlife[edit]

Barbados is host to four species of nesting turtles (green turtles, loggerheads, hawksbill turtles, and leatherbacks) and has the second-largest hawksbill turtle breeding population in the Caribbean.[54] The driving of vehicles on beaches can crush nests buried in the sand and such activity should be avoided in nesting areas.[55]

Barbados is also the host to the green monkey. The green monkey is found in West Africa from Senegal to the Volta River. It has been introduced to the Cape Verde islands off north-western Africa, and the West Indian islands of Saint Kitts, Nevis, Saint Martin, and Barbados. It was introduced to the West Indies in the late 17th century when slave trade ships travelled to the Caribbean from West Africa.

Demographics[edit]

A bus stop in Barbados.

People shopping in the capital Bridgetown.

The 2010 national census conducted by the Barbados Statistical Service reported a resident population of 277,821, of which 133,018 were male and 144,803 were female.[56]

The life expectancy for Barbados residents as of 2011[update] is 74 years. The average life expectancy is 72 years for males and 77 years for females (2005).[1] Barbados and Japan have the highest per capita occurrences of centenarians in the world.[57]

The crude birth rate is 12.23 births per 1,000 people, and the crude death rate is 8.39 deaths per 1,000 people. The infant mortality rate is 11.63 infant deaths per 1,000 live births.

Ethnic groups[edit]

Close to 90% of all Barbadians (also known colloquially as "Bajan") are of Afro-Caribbean descent ("Afro-Bajans") and mixed-descent. The remainder of the population includes groups of Europeans ("Anglo-Bajans" / "Euro-Bajans") mainly from the United Kingdom and Ireland, along with Asians, predominantly Chinese and Indians (both Hindu and Muslim).

Other groups in Barbados include people from the United Kingdom, United States and Canada. Barbadians who return after years of residence in the United States and children born in America to Bajan parents are called "Bajan Yankees", a term considered derogatory by some.[58] Generally, Bajans recognise and accept all "children of the island" as Bajans, and refer to each other as such.

The biggest communities outside the Afro-Caribbean community are:

- The Indo-Guyanese, an important part of the economy due to the increase of immigrants from partner country Guyana. There are reports of a growing Indo-Bajan diaspora originating from Guyana and India starting around 1990. Predominantly from southern India and Hindu states, they are growing in size but smaller than the equivalent communities in Trinidad and Guyana.[59]

- Euro-Bajans (6% of the population)[1] have settled in Barbados since the 17th century, originating from England, Ireland and Scotland. In 1643, there were 37,200 whites in Barbados (86% of the population).[60] More commonly they are known as "White Bajans". Euro-Bajans introduced folk music, such as Irish music and Highland music, and certain place names, such as "Scotland", a mountainous region. Among White Barbadians there exists an underclass known as Redlegs; mostly the descendants of Irish indentured labourers and prisoners imported to the island.[61] Many additionally moved on to become the earliest settlers of modern-day North and South Carolina in the United States.

- Chinese-Barbadians are a small portion of Barbados's Asian demographics. Most if not all first arrived in the 1940s during the Second World War. Many Chinese-Bajans have the surnames Chin, Chynn or Lee, although other surnames prevail in certain areas of the island. Chinese food and culture is becoming part of everyday Bajan culture.

- Lebanese and Syrians form the island's Arab Barbadian community, which is overwhelmingly Christian Arab. The Muslim Arab minority among Arab Barbadian make up a small percentage of the overall minority Muslim Barbadian population. The majority of the Lebanese and Syrians arrived in Barbados through trade opportunities. Their numbers are falling due to emigration to other countries.

- The Muslim Barbadians of Indian origin are largely of Gujarati ancestry. Many small businesses in Barbados are run and operated by Muslim-Indian Bajans.[62][63]

Languages[edit]

English is the official language of Barbados, and is used for communications, administration, and public services all over the island. In its capacity as the official language of the country, the standard of English tends to conform to the vocabulary, pronunciations, spellings, and conventions akin to, but not exactly the same as, those of British English.

An English-based creole language, referred to locally as Bajan, is spoken by most Barbadians in everyday life, especially in informal settings. In its full-fledged form, Bajan sounds markedly different from the Standard English heard on the island. The degree of intelligibility between Bajan and general English, for the general English speaker, depends on the level of creolised vocabulary and idioms. A Bajan speaker may be completely unintelligible to an English speaker from another country.

Religion[edit]

Cathedral Church of Saint Michael and All Angels, Bridgetown

Religion in Barbados (2000)[64]

Anglican (28.28%)

Pentecostal (18.69%)

No religion (atheism, agnosticism, etc) (17.30%)

Other (7.36%)

Seventh Day Adventist (5.49%)

Methodist (5.07%)

Baptist (4.79%)

Roman Catholic (4.18%)

Not Stated (3.28%)

Church of God (1.99%)

Jehovah's witnesses (1.96%)

Moravian (1.34%)

Rastafarian (1.14%)

Muslim (0.66%)

Brethren (0.64%)

Salvation Army (0.42%)

Hindu (0.34%)

Bahá'í (0.04%)

Most Barbadians of African and European descent are Christians (95%), the largest denomination being Anglican (40%). Other Christian denominations with significant followings in Barbados are the Catholic Church (administered by Roman Catholic Diocese of Bridgetown), Pentecostals, Jehovah's Witnesses, the Seventh-day Adventist Church and Spiritual Baptists. The Church of England was the official state religion until its legal disestablishment by the Parliament of Barbados following independence.[65]

Other religions in Barbados include Hinduism, Islam, and Bahá'í,[66]

Government and politics[edit]

The Barbados parliament building in Bridgetown.

Barbados has been an independent country since 30 November 1966.[67] It functions as a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy modelled on the British Westminster system. The British and Barbadian monarch—Queen Elizabeth II—is head of state and is represented locally by the Governor-General of Barbados—presently Sandra Mason. Both are advised on matters of the Barbadian state by the Prime Minister of Barbados, who is head of government. There are 30 representatives within the House of Assembly.

The Constitution of Barbados is the supreme law of the nation.[68] The Attorney General heads the independent judiciary. New Acts are passed by the Barbadian Parliament and require royal assent by the governor-general to become law.

During the 1990s at the suggestion of Trinidad and Tobago's Patrick Manning, Barbados attempted a political union with Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana. The project stalled after the then prime minister of Barbados, Lloyd Erskine Sandiford, became ill and his Democratic Labour Party lost the next general election.[69][70] Barbados continues to share close ties with Trinidad and Tobago and with Guyana, claiming the highest number of Guyanese immigrants after the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

Political culture[edit]

Barbados functions as a two-party system. The dominant political parties are the Democratic Labour Party and the incumbent Barbados Labour Party. Since Independence on 30 November 1966, the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) has governed from 1966 to 1976; 1986 to 1994; and from 2008 to 2018; and the Barbados Labour Party (BLP) has also governed from 1976 to 1986; 1994 to 2008; and from 2018 to present. The Democratic Labour Party government (DLP) held office with the then incomparable 1st Premier of Barbados became Prime Minister of Barbados, Errol Barrow from 4 December 1961 to 3 November 1966; 3 November 1966 to 9 September 1971; and from 9 September 1971 to 2 September 1976; and again from 28 May 1986 until his sudden death in office on 1 June 1987 for the then 4th Prime Minister of Barbados, Sir. Lloyd Sandiford with the Democratic Labour Party government (DLP) from 1 June 1987 to 20 January 1991; and from 20 January 1991 to 6 September 1994; the Barbados Labour Party government (BLP) held office with the then incomparable Prime Minister of Barbados, Tom Adams from 2 September 1976 to 18 June 1981; and from 18 June 1981 until his sudden death in office on 11 March 1985 for the then incomparable 3rd Prime Minister of Barbados, Sir. Harold St. John with the Barbados Labour Party government (BLP) from 11 March 1985 to 28 May 1986; the Barbados Labour Party government (BLP) held power from 6 September 1994 to 20 January 1999; 20 January 1999 to 21 May 2003; and from 21 May 2003 to 15 January 2008; the Democratic Labour Party government (DLP) held power with the then incomparable 6th Prime Minister of Barbados, David Thompson from 15 January 2008 until his death in office on 23 October 2010 for the then 7th Prime Minister of Barbados, Freundel Stuart with the Democratic Labour Party government (DLP) from 23 October 2010 to 21 February 2013; and from 21 February 2013 to 24 May 2018 for the general elections for the new Barbados Labour Party government (BLP). All of Barbados's Prime Ministers, except Freundel Stuart, held under the Ministry of Finance's portfolio. The Barbados Labour Party government (BLP) held power with the now 8th Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley from 24 May 2018 to present.

Foreign relations[edit]

Barbados is a full and participating member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME), and the Association of Caribbean States (ACS).[71]Organization of American States (OAS), Commonwealth of Nations, and the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ). In 2005 the Parliament of Barbados voted on a measure replacing the UK's Judicial Committee of the Privy Council with the Caribbean Court of Justice based in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago.

World Trade Organization, European Commission, CARIFORUM[edit]

Barbados is an original member (1995) of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and participates actively in its work. It grants at least MFN treatment to all its trading partners. European Union relations and cooperation with Barbados are carried out both on a bilateral and a regional basis. Barbados is party to the Cotonou Agreement, through which As of December 2007[update] it is linked by an Economic Partnership Agreement with the European Commission. The pact involves the Caribbean Forum (CARIFORUM) subgroup of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP). CARIFORUM is the only part of the wider ACP-bloc that has concluded the full regional trade-pact with the European Union. There are also ongoing EU-Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) and EU-CARIFORUM dialogues.[72]

Trade policy has also sought to protect a small number of domestic activities, mostly food production, from foreign competition, while recognising that most domestic needs are best met by imports.

The Double Taxation Relief (CARICOM) Treaty 1994[edit]

On 6 July 1994, at the Sherbourne Conference Centre, St. Michael, Barbados, representatives of eight (8) countries signed the Double Taxation Relief (CARICOM) Treaties 1994. The countries which were represented were: Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines and Trinidad and Tobago.[73]

On 19 August 1994 a representative of the Government of Guyana signed a similar treaty.

European Nations[edit]

In 2013, CARICOM called for European nations to pay reparations for slavery and established an official reparations commission.[74]

Military[edit]

The Barbados Defence Force has roughly 600 members. Within it, 12- to 18-year-olds make up the Barbados Cadet Corps. The defence preparations of the island nation are closely tied to defence treaties with the United Kingdom, the United States, and the People's Republic of China.[75]

The Royal Barbados Police Force is the sole law enforcement agency on the island of Barbados.

Administrative divisions[edit]

Barbados is divided into 11 parishes:

|

|

St. George and St. Thomas are in the middle of the country and are the only parishes without coastlines.

Human rights[edit]

Buggery, the colonial era law remains illegal in Barbados and bears a maximum sentence of life in prison; however, the law is very rarely enforced.[76]

Economy[edit]

Sandy Lane is a leading resort in Barbados's tourism sector

A proportional representation of national exports.

Barbados is the 53rd richest country in the world in terms of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per capita,[3] has a well-developed mixed economy, and a moderately high standard of living. According to the World Bank, Barbados is classified as being in its 66 top high income economies of the world.[77][not in citation given]

A 2012 self-study in conjunction with the Caribbean Development Bank revealed 20% of Barbadians live in poverty, and nearly 10% cannot meet their basic daily food needs.[78]

Historically, the economy of Barbados had been dependent on sugarcane cultivation and related activities, but since the late 1970s and early 1980s it has diversified into the manufacturing and tourism sectors. Offshore finance and information services have become important foreign exchange earners, and there is a healthy light manufacturing sector. Since the 1990s the Barbados Government has been seen as business-friendly and economically sound.[79][citation needed] The island saw a construction boom, with the development and redevelopment of hotels, office complexes, and homes. This slowed during the 2008 to 2011 world economic crisis and the recession.[80]

Harrison's Cave and Welchman Hall Gully have been developed as tourist attractions.

Recent government administrations have continued efforts to reduce unemployment, encourage foreign direct investment, and privatise remaining state-owned enterprises. Unemployment was reduced to 10.7% in 2003.[1] However, it has since increased to 11.9% in second quarter, 2015.[81]

There was a strong economy between 1999 and 2000 when it contracted in 2001 and 2002 due to slowdowns in tourism, consumer spending and the impact of the September 11, 2001 and July 7, 2005 terrorist attacks in New York, USA and London, England, UK, respectively, but rebounded in 2003 and has shown growth since 2004.[1] Traditional trading partners include Canada, the Caribbean Community (especially Trinidad and Tobago), the United Kingdom and the United States.

Business links and investment flows have become substantial: as of 2003[update] the island saw from Canada CA$ 25 billion in investment holdings, placing it as one of Canada's top five destinations for Canadian foreign direct investment (FDI). Businessman Eugene Melnyk of Toronto, Canada, is said to be one of Barbados's richest permanent residents.[82]

It has been reported that the year 2006 was one of the busiest years for building construction ever in Barbados, as the building-boom on the island entered the final stages for several multimillion-dollar commercial projects.[83]

The European Union is assisting Barbados with a €10 million program of modernisation of the country's International Business and Financial Services Sector.[84]

Barbados maintains the third largest stock exchange in the Caribbean region. As of 2009[update], officials at the stock exchange were investigating the possibility of augmenting the local exchange with an International Securities Market (ISM) venture.[85]

Barbados' outstanding debt climbed to $7.5 billion in May 2018 that is more than 1.7 times higher the GDP of the country. In June 2018 the government refused to pay coupon on Eurobonds maturing in 2035. Outstanding bond debt of Barbados reached $4.4 billion.[86]

Health[edit]

See Health in Barbados

Education[edit]

Schoolchildren in Saint Philip, Barbados.

The Barbados literacy rate is ranked close to 100%.[87] The mainstream public education system of Barbados is fashioned after the British model. The government of Barbados spends 6.7% of its GDP on education (2008).[1]

All young people in the country must attend school until age 16. Barbados has over 70 primary schools and over 20 secondary schools throughout the island. There are a number of private schools, including Montessori and the International Baccalaureate. Student enrolment at these schools represents less than 5% of the total enrolment of the public schools.

Degree-level education in the country is provided by the Barbados Community College, the Samuel Jackman Prescod Institute of Technology, Codrington College, and the Cave Hill campus and Open Campus of the University of the West Indies. Barbados is also home to the American University of Integrative Sciences, School of Medicine.

Educational testing[edit]

Barbados Secondary School Entrance Examination: Children who are 11 years old but under 12 years old on 1 September in the year of the examination are required to write the examination as a means of allocation to secondary school.

Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC) examinations are usually taken by students after five years of secondary school and mark the end of standard secondary education. The CSEC examinations are equivalent to the Ordinary Level (O-Levels) examinations and are targeted toward students 16 and older.

Caribbean Advanced Proficiency Examinations (CAPE) are taken by students who have completed their secondary education and wish to continue their studies. Students who sit for the CAPE usually possess CSEC or an equivalent certification. The CAPE is equivalent to the British Advanced Levels (A-Levels), voluntary qualifications that are intended for university entrance.[88]

Culture[edit]

The culture of Barbados is a blend of West African, Creole, Indian and British cultures present in Barbados. Citizens are officially called Barbadians. The term "Bajan" (pronounced BAY-jun) may have come from a localised pronunciation of the word Barbadian, which at times can sound more like "Bar-bajan"; or, more likely, from English bay ("bayling"), Portuguese baiano.

The largest carnival-like cultural event that takes place on the island is the Crop Over festival, which was established in 1974. As in many other Caribbean and Latin American countries, Crop Over is an important event for many people on the island, as well as the thousands of tourists that flock to there to participate in the annual events. The festival includes musical competitions and other traditional activities, and features the majority of the island's homegrown calypso and soca music for the year. The male and female Barbadians who harvested the most sugarcane are crowned as the King and Queen of the crop.[89] Crop Over gets under way at the beginning of July and ends with the costumed parade on Kadooment Day, held on the first Monday of August. New calypso/soca music Is usually released and played more frequently from the beginning of may to start the feeling of the festival.

Cuisine[edit]

Mount Gay Rum visitors centre

Bajan cuisine is a mixture of African, Indian, Irish, Creole and British influences. A typical meal consists of a main dish of meat or fish, normally marinated with a mixture of herbs and spices, hot side dishes, and one or more salads. The meal is usually served with one or more sauces.[90] The national dish of Barbados is Cou-Cou & Flying Fish with spicy gravy.[91] Another traditional meal is "Pudding and Souse" a dish of pickled pork with spiced sweet potatoes.[92] A wide variety of seafood and meats are also available.

The Mount Gay Rum visitors centre in Barbados claims to be the world's oldest remaining rum company, with earliest confirmed deed from 1703. Cockspur Rum and Malibu are also from the island. Barbados is home to the Banks Barbados Brewery, which brews Banks Beer, a pale lager, as well as Banks Amber Ale.[93] Banks also brews Tiger Malt, a non-alcoholic malted beverage. 10 Saints beer is brewed in Speightstown, St. Peter in Barbados and aged for 90 days in Mount Gay 'Special Reserve' Rum casks. It was first brewed in 2009 and is available in certain Caricom nations.[94]

Music[edit]

International pop star Rihanna, a native of Barbados.

In music, nine-time Grammy Award winner Rihanna (born in Saint Michael) is one of Barbados's best-known artists and one of the best selling music artists of all time, selling over 200 million records worldwide. In 2009 she was appointed as an Honorary Ambassador of Youth and Culture for Barbados by the late Prime Minister, David Thompson.[95]

Singer-songwriters Rayvon and Shontelle, the band Cover Drive, musician Rupee and Mark Morrison, singer of Top 10 hit "Return of the Mack" also originate from Barbados. Grandmaster Flash (born Joseph Saddler in Bridgetown in 1958) is a hugely influential musician of Barbadian origin, pioneering hip-hop DJing, cutting, and mixing in 1970s New York. The Merrymen are a well known Calypso band based in Barbados, performing from the 1960s into the 2010s.

Public holidays[edit]

| Date | English name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year's Day | |

| 21 January | Errol Barrow Day | A day of recognition for Errol Barrow the Father of the Nation since 21 January 1989. |

| March or April | Good Friday | Friday, date varies |

| March or April | Easter Monday | Monday, date varies |

| 28 April | National Heroes' Day | A day of recognition for Barbados's national heroes since 28 April 1998. |

| 1–7 May | Labour Day | 1st Monday in May, date varies |

| May or June | Whit Monday | Monday, date varies |

| 1 August | Emancipation Day | The date on which slavery was abolished on the island since 1 August 1997. |

| 1–7 August | Kadooment Day | 1st Monday in August, date varies |

30 November | Independence Day | The anniversary of Barbadian national independence, from the United Kingdom on 30 November 1966. |

| 25 December | Christmas Day | |

| 26 December. | Boxing Day |

Tourism[edit]

Like many other Caribbean islands, Barbados is famed for its white-sand beaches and turquoise,crystalline waters. Popular destinations include[96]

Harrison's cave- Opened in 1981, Harrison cave is noted for its extremely pure water.[97]

Flowers Forest Park- in the village of Saint Joseph of Bloomsbury.

Hillaby mountain- Hillaby, at approximately 340 meters above sea level is the highest point of the East Caribbean mountains.

With a passport in hand, tourists can enjoy tax-free shopping at a variety of stores on the island.[98]

Sports[edit]

Kensington Oval in Bridgetown hosted the 2007 Cricket World Cup final. Cricket is one of the most followed games in Barbados and Kensington Oval is often referred to as the "Mecca in Cricket" due to its significance and contributions to the sport.

A horse and rider at Garrison Savannah

As in other Caribbean countries of British colonial heritage, cricket is very popular on the island. The West Indies cricket team usually includes several Barbadian players. In addition to several warm-up matches and six "Super Eight" matches, the country hosted the final of the 2007 Cricket World Cup. Barbados has produced many great cricketers including Sir Garfield Sobers, Sir Frank Worrell, Sir Clyde Walcott, Sir Everton Weekes, Gordon Greenidge, Wes Hall, Charlie Griffith, Joel Garner, Desmond Haynes and Malcolm Marshall.

Rugby is also popular in Barbados as well.

Horse racing takes place at the Historic Garrison Savannah close to Bridgetown. Spectators can pay for admission to the stands, or else can watch races from the public "rail", which encompasses the track.

Basketball is an increasingly popular sport, played at school or college. Barbados's national team has shown some unexpected results as in the past it beat many much larger countries.

Polo is very popular amongst the rich elite on the island and the "High-Goal" Apes Hill team is based at the St James's Club.[99] It is also played at the private Holders Festival ground.

In golf, the Barbados Open, played at Royal Westmoreland Golf Club, was an annual stop on the European Seniors Tour from 2000 to 2009. In December 2006 the WGC-World Cup took place at the country's Sandy Lane resort on the Country Club course, an 18-hole course designed by Tom Fazio. The Barbados Golf Club is another course on the island. It has hosted the Barbados Open on several occasions.

Volleyball is also popular, though volleyball is mainly played indoors.

Tennis is gaining popularity and Barbados is home to Darian King, currently ranked 270th in the world and is the 2nd highest ranked player in the Caribbean.

Motorsports also play a role, with Rally Barbados occurring each summer and being listed on the FIA NACAM calendar. Also, the Bushy Park Circuit hosted the Race of Champions and Global RallyCross Championship in 2014.

The presence of the trade winds along with favourable swells make the southern tip of the island an ideal location for wave sailing (an extreme form of the sport of windsurfing).

Netball is also popular with women in Barbados.

Barbadian team The Flyin' Fish, are the 2009 Segway Polo World Champions.[100]

Transport[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

A Hino ACME Minibus B 163 in Speightstown, St. Peter, Barbados.

Although Barbados is about 34 km (21 mi) across at its widest point, a car journey from Six Cross Roads in St. Philip (south-east) to North Point in St. Lucy (north-central) can take one and a half hours or longer due to road conditions. Barbados has half as many registered cars as citizens.

Transport on the island is relatively convenient with "route taxis" called "ZRs" (pronounced "Zed-Rs") travelling to most points on the island. These small buses can at times be crowded, as passengers are generally never turned down regardless of the number. They will usually take the more scenic routes to destinations. They generally depart from the capital Bridgetown or from Speightstown in the northern part of the island.

Including the ZRs, there are three bus systems running seven days a week (though less frequently on Sundays). There are ZRs, the yellow minibuses and the blue Transport Board buses. A ride on any of them costs BBD$2.00. The smaller buses from the two privately owned systems ("ZRs" and "minibuses") can give change; the larger blue buses from the government-operated Barbados Transport Board system cannot, but do give receipts. The Barbados Transport Board buses travel in regular bus routes and scheduled timetables across Barbados. Schoolchildren in school uniform including some Secondary schools ride for free on the government buses and for $2.00 on the ZRs. Most routes require a connection in Bridgetown. Barbados Transport Board's headquarters are located at Kay's House, Roebuck Street, St. Michael, and the bus depots and terminals are located in the Fairchild Street Bus Terminal in Fairchild Street and the Princess Alice Bus Terminal (which was formerly the Lower Green Bus Terminal in Jubilee Gardens, Bridgetown, St. Michael) in Princess Alice Highway, Bridgetown, St. Michael; the Speightstown Bus Terminal in Speightstown, St. Peter; the Oistins Bus Depot in Oistins, Christ Church; and the Mangrove Bus Depot in Mangrove, St. Philip.

Some hotels also provide visitors with shuttles to points of interest on the island from outside the hotel lobby. There are several locally owned and operated vehicle rental agencies in Barbados but there are no multi-national companies.

The island's lone airport is the Grantley Adams International Airport. It receives daily flights by several major airlines from points around the globe, as well as several smaller regional commercial airlines and charters. The airport serves as the main air-transportation hub for the eastern Caribbean. In the first decade of the 21st century it underwent a US$100 million upgrade and expansion in February 2003 until completion in August 2005.

There was also a helicopter shuttle service, which offered air taxi services to a number of sites around the island, mainly on the West Coast tourist belt. Air and maritime traffic was regulated by the Barbados Port Authority. Private Luxury Helicopter Tours were located in Spencers, Christ Church next to the Barbados Concorde Experience when it was opened in September 2007 and closed in April 2010. Bajan Helicopters were opened in April 1989 and closed in late December 2009 because of the economic crisis and recession facing Barbados.

Notable people[edit]

See also[edit]

- Outline of Barbados

- Index of Barbados-related articles

References[edit]

^ abcdefg Barbados CIA World Factbook

^ "Barbados – General Information". GeoHive. Retrieved 16 December 2013..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ abcde Barbados, International Monetary Fund.

^ "2018 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

^ "Barbados". 29 August 2006. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. (fco.gov.uk), updated 5 June 2006.

^ Chapter 4 – The Windward Islands and Barbados – U.S. Library of Congress

^ ab Sauer, Carl Ortwin (1969) [1966]. Early Spanish Main, The. University of California Press. pp. 192–197. ISBN 0-520-01415-4.

^ The Jewish Experience in 17th century Barbados, By Ryan Hechler, The VCU Menorah Review at Virginia Commonwealth University

^ Secretariat. "Barbados – History". Commonwealth of Nations. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014.

^ HRM Queen Elizabeth II (2010). "History and present government – Barbados". The Royal Household. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

^ "World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision". ESA.UN.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

^ "AXSES Systems Caribbean Inc., The Barbados Tourism Encyclopaedia". Barbados.org. 8 February 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

^ "Britannica Encyclopaedia: History of Barbados". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

^ Barbados the Red Land with White Teeth: Home of the Amerindians. Barbados Museum & Historical Society. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.A temporary exhibit which examined some of the preliminary excavations conducted at the dig site at Heywoods, St. Peter.

^ Barbados – Geography / History. Fun 'N' Sun Publishing Inc. 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

^ Faria, Norman (17 June 2009). "Guyana Consul (Barbados) Visit to Former Amerindian Village Site in B'dos" (PDF). Guyana Chronicle. Pan-Tribal Confederacy of Indigenous Tribal Nations. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2010.Adjacent to the park, there is still a fresh water stream. This as a main reason the village was here. A hundred or so metres away is the sea and a further five hundred metres [550 yd] out across a lagoon was the outlying reef where the Atlantic swells broke on the coral in shallow waters. As an aside, the word "Ichirouganaim", said to be an Arawak word used by the Amerindians to describe Barbados, is thought to refer to the "teeth" imagery of the waves breaking on the reefs off most of southern and eastern coasts.

^ Drewett, Peter (1991). Prehistoric Barbados. Barbados Museum and Historical Society. ISBN 1-873132-15-8.

^ Drewett, Peter (2000). Prehistoric Settlements in the Caribbean: Fieldwork on Barbados, Tortola and the Cayman Islands. Archetype Publications Ltd. ISBN 1-873132-22-0.

^ abc Carrington, Sean (2007). A~Z of Barbados Heritage. Macmillan Caribbean Publishers Limited. p. 25. ISBN 0-333-92068-6.

^ Allsopp, Richard; Allsopp, Jeannette (2003). Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. University of the West Indies Press. p. 101. ISBN 9766401454.

^ Eltis, David; Richardson, David (1997). Routes to Slavery: Direction, Ethnicity, and Mortality in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7146-4820-0. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

^ Morgan, Philip D.; Hawkins, Sean (2004). Black Experience and the Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-19-926029-X.

^ Beckles, Hilary. A History of Barbados: From Amerindian Settlement to Caribbean Single Market (Cambridge University Press, 2007 edition).

^ "Origin of the Eagle Clan", Pan-Tribal Confederacy of Indigenous Tribal Nations.

^ Descendants of Princess Marian. (PDF). Retrieved 19 February 2012.

^ Corish, Patrick J. Patrick J. Corish, The Cromwellian Regime, 1650–1660. oup.com. pp. 353–386. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199562527.003.0014.

^ "Barbados". Library of Congress Country Studies.

^ "Barbados – population". Library of Congress Country Studies.

^ William And John, 11 January 201, Shipstamps.co.uk

^ Beckles p. 7.

^ "Holetown Barbados – Fun Barbados Sights". www.funbarbados.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

^ Karl Watson, The Civil War in Barbados, History in-depth, BBC, 5 November 2009.

^ "New Take on George Slept Here". The Boston Globe.

^ ab Ali, Arif (1997). Barbados: Just Beyond Your Imagination. Hansib Publishing (Caribbean) Ltd. pp. 46, 48. ISBN 1-870518-54-3.

^ A Relation... in: "Alice Curwen", Autobiographical Writings by Early Quaker Women (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2004), ed. David Booy.

^ Logan, Gabi. "Geologic History of Barbados Beaches". USA Today. Retrieved 2 July 2011.Barbados lies directly over the intersection of the Caribbean plate and the South American plate in a region known as a subduction zone. Beneath the ocean floor, the South American plate slowly slides below the Caribbean plate.

^ "Barbados Sightseeing – Animal Flower Cave". Leigh Designs. Little Bay House. 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.The Animal flower Cave is the island's lone accessible sea-cave and was discovered from the sea in 1780 by two English explorers. The cave's coral floor is estimated to be 400,000 to 500,000 years old and the "younger" coral section above the floor is about 126,000 years old. The dating was carried out by the German Geographical Institute, and visitors can see a "map" of the dating work in the bar and restaurant. The cave now stands some six feet above the high tide mark even though it was formed at sea level. This is because Barbados is rising about one inch per 1,000 years, which is yet another indication of the cave's age.

^ Gloria. "Pico Teneriffe - Barbados Pocket Guide". www.barbadospocketguide.com.

^ "Average and Record Conditions at Bridgetown, Barbados". BBC Weather. Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

^ "Hurricane Tomas lashes Caribbean islands". BBC News, 30 October 2010.

^ Domestic and Industrial Wastewater Treatment Techniques in Barbados. Cep.unep.org. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

^ Barbados, World Resources Institute

^ Perspectives: A continuing problem and persistent threat Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine.. Barbadosadvocate.com. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

^ ab "PERSPECTIVES: Squatting – a continuing problem" Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine.. Barbadosadvocate.com (24 March 2008). Retrieved 20 April 2014.

^ "Squatters get thumbs down from MP Forde". Nationnews.com (30 June 2010). Retrieved 20 April 2014.

^ "Welcome to Coastal Zone Management Unit – Coastal Zone Management Unit".

^ Barbados' CZMU in demand Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine.. Barbadosadvocate.com (4 February 2012). Retrieved 20 April 2014.

^ Centre for Resource Management and Environmental Studies Archived 28 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine., The University of the West Indies.

^ Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles, UN-FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department

^ Prospero, Joseph M. (June 2006). "Saharan Dust Impacts and Climate Change" (PDF). Oceanography. 19 (2): 60–61. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-05.

^ The Effects of African Dust on Coral Reefs and Human Health. Coastal.er.usgs.gov (15 April 2014). Retrieved 20 April 2014.

^ When the Dust Settles (DAAC Study), NASA

^ The Impact of African Dust on Childhood Asthma Morbidity in Barbados Archived 24 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine.. Commprojects.jhsph.edu. Retrieved April 2014.

^ Caribbean Travel: Swim with the turtles in Barbados. Thestar.com (13 March 2012). Retrieved 20 April 2014.

^ Sea Turtles – Dive Operators Association of Barbados Archived 19 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Barbados Blue Inc.

^ 2010 Population and Housing Census (PDF) (Report). 1. Barbados Statistical Service. September 2013. p. i. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

^ Best, Tony (9 April 2005)"Bajan secrets to living long". Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2006. . nationnews.com.

^ Byfield, Judith Ann-Marie; Denzer, LaRay; Morrison, Anthea (2010). Gendering the African diaspora: women, culture, and historical change in the Caribbean and Nigerian hinterland. Indiana University Press. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-0-253-22153-7.

^ Are Guyanese welcome in Barbados?, 7 September 2006; British Broadcasting Corporation (Caribbean Bureau)

^ Watson, Karl (17 February 2011) "Slavery and Economy in Barbados", BBC.

^ Rodgers, Nini (November 2007). "The Irish in the Caribbean 1641–1837: An Overview". Irish Migration Studies in Latin America. 5 (3): 145–156.

^ Amadou Mahtar M'Bow; M. Ali Kettani (2001). Islam and Muslims in the American Continent. Center of Historical, Economical and Social Studies.

^ Rhoda Reddock (1996). Ethnic minorities in Caribbean society. I.S.E.R., The University of the West Indies. ISBN 978-976-618-024-9.

^ [1]

^ Singh, Rajkumar (20 January 2006). "Parliament: Act of Parliament concerning the Anglican church". Caricomlaw.org. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

[dead link]

^ "Baha'u'llah". Bci.org. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

^ Fransman, Laurie (2011). Fransman's British Nationality Law. A&C Black. p. 848. ISBN 978-1-84592-095-1.

^ The official Constitution of Barbados (1966) version.

^ "Chasing after an elusive union". Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2010.. Jamaica Observer, 20 July 2003.

^ Former PM: Caribbean doing/un-doing everything again and again. NationNews.com. 14 July 2003

^ BarbadosBusiness.gov.bb, The Barbados government's Regional and International affiliations

^ "European Union – EEAS (European External Action Service) | EU Relations with Barbados". Europa (web portal). 19 June 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

^ REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO. "Legal Supplement" (PDF). www.ird.gov.tt.

^ "Slavery reparations: Blood money". The Economist. 5 October 2013.

^ "Barbados turns to China for military assistance". Caribbean360.com. 7 August 2006. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013.

^ "State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 17 May 2016.

^ World Bank – Country Groups. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

^ "20 percent in poverty". Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation. 20 April 2012. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

^ Publications, USA International Business (2007-09-04). Island States: Small Island States Handbook: Development Strategy and Programs. Int'l Business Publications. ISBN 9780739744871.

^ "BBC News – Barbados profile – Overview". British Broadcasting Corporation. 22 December 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

^ "Latest Socio-Economic Indicators". Barbados Statistical Service. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

^ "Melnyk – one of the wealthiest". NationNews.com. 29 October 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

^ Morris, Roy (2 January 2006). "Builders paradise". The Nation Newspaper. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 29 July 2009.Industry sources are warning, however, that while the boom will bring many jobs and much income, ordinary Barbadians hoping to undertake home construction or improvement will be hard pressed to find materials or labour, given the large number of massive commercial projects with which they will have to compete. ... Construction magnate Sir Charles 'COW' Williams, agreeing that this year will be "without doubt" the biggest ever for the island as far as construction was concerned, revealed that his organisation was in the final stages of the construction of a new $6 million plant at Lears, St Michael to double its capacity to produce concrete blocks, as well as a new $2 million plant to supply ready-mixed concrete from its fleet of trucks. "The important thing to keep in mind is that the country will benefit tremendously from a massive injection of foreign exchange from people who want to own homes here," Sir Charles said.

^ Lashley, Cathy (24 July 2009). "Barbados signs agreement with EU". gisbarbados.gov.bb. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

^ "Treaty network an advantage in securities trading". Barbados Advocate. 28 July 2009. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

^ "Barbados announced a technical default on coupon of Eurobonds with maturity in 2035". www.cbonds.com. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

^ "Unesco Institute for Statistics: Date Centre". 14 September 2007. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

^ "The Education System in Barbados – Business Barbados". Business Barbados.

^ "Crop Over Festival". 2camels.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

^ Barbados Food. Totally Barbados. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

^ Barbados National Dish: Coucou & Flying Fish Archived 16 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. Epicurian Tourist. 25 December 2007. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

^ [2].www.barbados.org. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

^ Banks Beer: The Beer Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. BanksBeer.com. Retrieved 2011-3-9.

^ 10 Saints beer. BanksBeer.com. Retrieved 2011-3-9.

^ Kamugisha, Aaron (2015) Rihanna : Barbados world-gurl in global popular culture. University of the West Indies Press.

ISBN 9766405026

^ Tokmakoğlu, A. Buğra (16 December 2017). "Barbados'da Görmeniz Gereken 3 Yer | Turna.com". Turna.com Blog (in Turkish).

^ Guide, Barbados.org Travel. "Harrison's Cave, Barbados - The Ultimate Island Attraction". barbados.org.

^ Lynne Sullivan (2001). Adventure Guide to Barbados. Hunter Publishing, Inc. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-1-55650-910-0.

^ "Ape hills polo". Ape hills Club. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

^ Harris, Alan (26 July 2009). "Barbados Segway Polo team 2009 World Champions". Barbados Advocate. Archived from the original on 15 September 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

Further reading[edit]

- Burns, Sir Alan, History of the British West Indies. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1965.

Davis, David Brion. Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

ISBN 0-19-514073-7- Frere, Samuel, A Short History of Barbados: From its First Discovery and Settlement, to the End of the Year 1767. London: J. Dodsley, 1768.

- Gragg, Larry Dale, Englishmen transplanted: The English Colonization of Barbados, 1627–1660. Oxford University Press, 2003.

ISBN 978-0199253890 - Hamshere, Cyril, The British In the Caribbean. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

- Newman, Simon P. A New World of Labor: The Development of Slavery in the British Atlantic. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

ISBN 978-0812245196 - Northrup, David, ed. The Atlantic Slave Trade, Second Edition. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002.

ISBN 0-618-11624-9 - O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson, An Empire Divided: The American Revolution and the British Caribbean. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000.

ISBN 978-0812217322 - Rogozinski, January 1999. A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and Carib to the Present. Revised version, New York, USA.

ISBN 0-8160-3811-2 - Scott, Caroline 1999. Insight Guide Barbados. Discovery Channel and Insight Guides; fourth edition, Singapore.

ISBN 0-88729-033-7

Videography[edit]

Overview Video—Barbados Tourism Investment Inc. (Courtesy of US Television).

Videography on YouTube, by the Ministry of Energy and the Environment, under the Office of the Prime Minister.

Sandy Lane Hotel, Barbados 11 November 2011, on Where in the World is Matt Lauer?, NBC Today Show. This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook document "2003 edition".

This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook document "2003 edition".

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Official webpage of Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Barbados

- Parliament of Barbados official website

Barbados Tourism Authority—The Ministry of Tourism- Central Bank of Barbados website

- Barbados Investment and Development Corporation

- Barbados Maritime Ship Registry

- Barbados Museum & Historical Society

General information

Barbados at Curlie Wikimedia Atlas of Barbados

Wikimedia Atlas of Barbados