Willem de Kooning

| Willem de Kooning | |

|---|---|

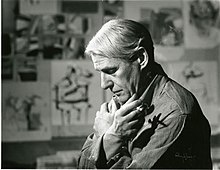

De Kooning in his studio in 1961 | |

| Born | (1904-04-24)April 24, 1904 Rotterdam, Netherlands |

| Died | March 19, 1997(1997-03-19) (aged 92) East Hampton, New York, U.S.[1] |

| Nationality | Dutch, American |

| Known for | Abstract expressionism |

| Notable work | Woman I, Easter Monday, Attic, Excavation |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (1964) National Medal of Arts (1986) Praemium Imperiale (1989) |

Willem de Kooning (/də ˈkuːnɪŋ/;[2]Dutch: [ˈʋɪləm də ˈkoːnɪŋ]; April 24, 1904 – March 19, 1997) was a Dutch abstract expressionist artist. He was born in Rotterdam, in the Netherlands. He moved to the United States in 1926, and became an American citizen in 1962.[3] On December 9, 1943, he married painter Elaine Fried.

In the years after World War II, de Kooning painted in a style that came to be referred to as abstract expressionism or "action painting", and was part of a group of artists that came to be known as the New York School. Other painters in this group included Jackson Pollock, Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Franz Kline, Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko, Hans Hofmann, Adolph Gottlieb, Anne Ryan, Robert Motherwell, Philip Guston, Clyfford Still, and Richard Pousette-Dart.

Contents

1 Biography

2 Marriage to Elaine de Kooning

3 Work

3.1 Early work

3.2 Black and white abstracts

3.3 The Woman series

3.4 Notable works

4 Market reception

5 Solo exhibitions

6 See also

7 References

8 Further reading

9 External links

Biography

Willem de Kooning (1968)

Willem de Kooning was born in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, on April 24, 1904. His parents, Leendert de Kooning and Cornelia Nobel, were divorced in 1907, and de Kooning lived first with his father and then with his mother. He left school in 1916 and became an apprentice in a firm of commercial artists. Until 1924 he attended evening classes at the Academie van Beeldende Kunsten en Technische Wetenschappen (the academy of fine arts and applied sciences of Rotterdam), now the Willem de Kooning Academie.[3]

In 1926 de Kooning travelled to the United States as a stowaway on the Shelley, a British freighter bound for Argentina, and on August 15 landed at Newport News, Virginia. He stayed at the Dutch Seamen's Home in Hoboken, New Jersey, and found work as a house-painter. In 1927 he moved to Manhattan, where he had a studio on West Forty-fourth Street. He supported himself with jobs in carpentry, house-painting and commercial art.[3]

De Kooning began painting in his free time and in 1928 he joined the art colony at Woodstock, New York. He also began to meet some of the modernist artists active in Manhattan. Among them were the American Stuart Davis, the Armenian Arshile Gorky and the Russian John Graham, whom de Kooning collectively called the "Three Musketeers".[4]:98 Gorky, whom de Kooning first met at the home of Misha Reznikoff, became a close friend and, for at least ten years, an important influence.[4]:100Balcomb Greene said that "de Kooning virtually worshipped Gorky"; according to Aristodimos Kaldis, "Gorky was de Kooning's master".[4]:184 De Kooning's drawing Self-portrait with Imaginary Brother, from about 1938, may show him with Gorky; the pose of the figures is that of a photograph of Gorky with Peter Busa in about 1936.[4]:184

De Kooning joined the Artists Union in 1934, and in 1935 was employed in the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration, for which he designed a number of murals including some for the Williamsburg Federal Housing Project in Brooklyn. None of them were executed,[1] but a sketch for one was included in New Horizons in American Art at the Museum of Modern Art, his first group show. Starting in 1937, when De Kooning had to leave the Federal Art Project because he did not have American citizenship, he began to work full-time as an artist, earning income from commissions and by giving lessons.[3] That year de Kooning was assigned to a portion of the mural Medicine for the Hall of Pharmacy at the 1939 World's Fair in New York, which drew the attention of critics, the images themselves so completely new and distinct from the era of American realism.

De Kooning met his wife, Elaine Fried, at the American Artists School in New York. She was 14 years his junior. Thus was to begin a lifelong partnership affected by alcoholism, lack of money, love affairs, quarrels and separations. They were married on December 9, 1943. De Kooning worked on his first series of portrait paintings: standing or sedentary men like Two Men Standing, Man, and Seated Figure (Classic Male), even combining with self-portraits as with Portrait with Imaginary Brother (1938–39). At this time, de Kooning's work borrowed strongly from Gorky's surrealist imagery and was influenced by Picasso. This changed only when de Kooning met the younger painter Franz Kline, who was also working with the figurative style of American realism and had been drawn to monochrome. Kline, who died young, was one of de Kooning's closest artist friends. Kline's influence is evident in de Kooning's calligraphic black images of this period.

In the late 1950s, de Kooning's work shifted away from the figurative work of the women (though he would return to that subject matter on occasion) and began to display an interest in more abstract, less representational imagery.[citation needed] He became a US citizen on 13 March 1962, and in the following year moved from Broadway to a small house in East Hampton, a house which Elaine's brother Peter Fried had sold to him two years before. He built a studio near by, and lived in the house to the end of his life.[3][5]

It was revealed that, toward the end of his life, de Kooning had begun to lose his memory in the late 1980s and had been suffering from Alzheimer's disease for some time.[5] This revelation has initiated considerable debate among scholars and critics about how responsible de Kooning was for the creation of his late work.[6]

Succumbing to the progression of his disease, de Kooning painted his final works in 1991. He died in 1997 at the age of 93 and was cremated.[citation needed]

Marriage to Elaine de Kooning

Elaine had admired Willem's artwork before meeting him; in 1938 her teacher introduced her to Willem de Kooning at a Manhattan cafeteria when she was 20 and he 34. After meeting, he began to instruct her in drawing and painting. They painted in Willem's loft at 143 West 21st Street, and he was known for his harsh criticism of her work, "sternly requiring that she draw and redraw a figure or still life and insisting on fine, accurate, clear linear definition supported by precisely modulated shading."[7] He even destroyed many of her drawings, but this "impelled Elaine to strive for both precision and grace in her work".[7] When they married in 1943, she moved into his loft and they continued sharing studio spaces.[7]

Elaine and Willem de Kooning had what was later called an open marriage; they both were casual about sex and about each other's affairs. Elaine had affairs with men who helped further Willem's career, such as Harold Rosenberg, who was a renowned art critic, Thomas B. Hess, who was a writer about art and managing editor for Artnews, and Charles Egan, owner of the Charles Egan Gallery. Willem had a daughter, Lisa de Kooning, in 1956, as a result of his affair with Joan Ward.[7]

Elaine and Willem both struggled with alcoholism, which eventually led to their separation in 1957.[7] While separated, Elaine remained in New York, struggling with poverty, and Willem moved to Long Island and dealt with depression. Despite bouts with alcoholism, they both continued painting. Although separated for nearly twenty years, they never divorced, and ultimately reunited in 1976.[7]

Work

Early work

De Kooning's paintings of the 1930s and early 1940s are abstract still-lifes characterised by geometric or biomorphic shapes and strong colours. They show the influence of his friends Davis, Gorky and Graham, but also of Arp, Joan Miró, Mondrian and Pablo Picasso.[1] In the same years de Kooning also painted a series of solitary male figures, either standing or seated, against undefined backgrounds; many of these are unfinished.[1][3]

Black and white abstracts

By 1946, de Kooning had begun a series of black and white paintings, which he would continue into 1949. During this period he had his first one-man show at the Charles Egan Gallery in 1948 consisting largely of black and white works, although a few pieces have passages of bright color. De Kooning's black paintings are important to the history of abstract expressionism owing to their densely impacted forms, their mixed media, and their technique.[8]:25

Woman III, 1953, private collection

The Woman series

De Kooning's well-known Woman series, begun in 1950 and culminating in Woman VI, owes much to Picasso, not least in the aggressive, penetrative breaking apart of the figure, and the spaces around it. Picasso's late works show signs that he, in turn, saw images of works by Pollock and de Kooning.[9]:17

De Kooning led the 1950s art world into a new movement known as American abstract expressionism. "From 1940 to the present, Woman has manifested herself in de Kooning's paintings and drawings as at once the focus of desire, frustration, inner conflict, pleasure, … and as posing problems of conception and handling as demanding as those of an engineer."[10] The female figure is an important symbol for de Kooning's art career and his own life. The Woman painting is considered as a significant work of art for the museum through its historical context about the post-World War II history and American feminist movement. Additionally, the medium (oil, enamel, and charcoal on canvas) of this painting makes it different from others of de Kooning's time.

De Kooning as sculptor: Seated Woman on a Bench, bronze of 1972 (cast 1976), in the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Notable works

The painter is noted for his paintings: Woman III (1953), Woman VI (1953), Interchange (1955), and Police Gazette (1955). Some notable sculptures are Clamdigger (1972/1976) and Seated Woman on a Bench (1972/1976).

Market reception

Some of de Kooning's paintings have been sold in the 21st century for near record prices. In November 2006, David Geffen sold his oil painting Woman III to Steven A. Cohen for $137.5 million, just below the record at the time of $140 million, which involved the same people in the same month for Jackson Pollock's No. 5, 1948.[11] A month earlier Cohen had already paid Geffen $63.5 million for Police Gazette by de Kooning.[12] In September 2015 David Geffen sold de Kooning's oil painting Interchange for $300 million to hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin.[13] As of 2017, this de Kooning painting was displaced by the da Vinci Salvator Mundi as receiving the highest price paid for a painting, which in 2016 was almost matched by the sale of Paul Gauguin's When Will You Marry? in February 2015 for close to $300 million. In November 2016, Untitled XXV sold for $66.3 million at Christie's in New York. This was a record price for a Kooning piece sold at auction.[14]

The painting by Leonardo which displaced the de Kooning oil work as the most expensive painting sold was Salvator Mundi, depicting Jesus Christ holding an orb, sold for a world record $450.3 million at a Christie's auction in New York on 15 November 2017.[15] The highest price previously paid for a work of art at auction was for Pablo Picasso's Les Femmes d'Alger, which sold for $179.4 million in May 2015 at Christie's New York.[16]

Solo exhibitions

The artist was featured in a number of solo exhibitions from 1948 to 1966, many in New York but also nationally and internationally. Specifically, he had fourteen separate exhibitions and even had two exhibitions per annum in the years 1953, 1964, and 1965. He was featured at the Egan Gallery, the Sidney Janis Gallery, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Arts Club of Chicago, the Martha Jackson Gallery, the Workshop Center, the Paul Kantor Gallery, the Hames Goodman Gallery, the Allan Stone Gallery, and the Smith College Museum of Art. Most of the exhibitions lasted for 3 weeks to one month.[8]:126

See also

- Abstract expressionism

- Action painting

- American Figurative Expressionism

- New York Figurative Expressionism

- Elaine de Kooning

- Impasto

- Women in art

- Erased de Kooning Drawing

References

^ abcd Christoph Grunenberg, et al. (2011). De Kooning: (1) Willem de Kooning. Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed February 2015. (subscription required)

^ "de Kooning". The Collins English Dictionary, online edition. London: HarperCollins Publishers.

^ abcdef Tracy Schpero Fitzpatrick (2001). de Kooning, Willem. American National Biography Online, January 2001 update. Accessed February 2015. (subscription required)

^ abcd Matthew Spender (1999). From a High Place: a Life of Arshile Gorky. New York: Knopf. .mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

ISBN 9780375403781.

^ ab "Willem de Kooning Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works". The Art Story. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

^ Swinnen, Aafje, and Mark Schweda. 2015. Popularizing Dementia: Public Expressions and Representations of Forgetfulness. Bielefeld: Transcript. p. 150.

ISBN 9783837627107.

^ abcdef Hall, Lee. Elaine and Bill: Portrait of a Marriage.

^ ab Harry F. Gaugh (1983). Willem de Kooning. New York: Abbeville Press.

ISBN 9780896593329.

^ Terry Smith (2011). Contemporary art: world currents. Upper Saddle River, [NJ]: Prentice Hall.

ISBN 9780205034406.

^ Willem de Kooning. Text by Harold Rosenberg. 29

^ Carol Vogel, Landmark De Kooning Crowns Collection, The New York Times, November 18, 2006

^ Carol Vogel, Works by Johns and de Kooning Sell for $143.5 Million, The New York Times, October 12, 2006

^ "Billionaire drops $500M for 2 masterpieces," Feb. 19, 2016, Bloomberg News, as republished by Fox News, at [1].

^ Duray, Dan (November 16, 2016). "De Kooning painting sells for record $66m at Christie's New York". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

^ Crow, Kelly (2017-11-16). "Leonardo da Vinci Painting 'Salvator Mundi' Sells for $450.3 Million". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

^ Leonardo da Vinci painting 'Salvator Mundi' sold for record $450.3 million, Fox News, 16 November 2017

Further reading

- Marika Herskovic, American Abstract and Figurative Expressionism Style Is Timely Art Is Timeless An Illustrated Survey With Artists' Statements, Artwork and Biographies. (New York School Press, 2009).

ISBN 978-0-9677994-2-1. pp. 76–79; p. 127; p. 136. - Marika Herskovic, American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s: An Illustrated Survey, (New York School Press, 2003).

ISBN 0-9677994-1-4. pp. 94–97. - Marika Herskovic, New York School Abstract Expressionists: Artists Choice by Artists, (New York School Press, 2000).

ISBN 0-9677994-0-6. p. 16; p. 36; p. 106–109. - Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, "de Kooning: An American Master",2004, Knopf, Borzoi Books

ISBN 1-4000-4175-9 - Edvard Lieber, Willem de Kooning: Reflections in the Studio, 2000, Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ISBN 0-8109-4560-6

ART USA NOW Ed. Lee Nordness; Vol.1, (Viking Press, 1963.) pp. 134–137.- The American Presidency Project

- Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts

- Richard Shiff, On "Between Sense and de Kooning", The Montréal Review, September 2011.

- Judith Zilczer, "Willem de Kooning." Phaidon Press, 2017.

ISBN 978-0-7148-7316-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Willem de Kooning. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Willem de Kooning |

Willem de Kooning at the Museum of Modern Art- Links to reproductions

Willem de Kooning at Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

Woman in the Pool (1969) Phoenix Art Museum- de Kooning's work in the Guggenheim Collection

- Willem de Kooning in the National Gallery of Australia's Kenneth Tyler collection

Sam Hunter, "Willem de Kooning Lecture", The Baltimore Museum of Art: Baltimore, Maryland, 1964 Retrieved June 26, 2012- Frank O'Hara — Rainbow Warrior

- A small-town couple left behind a stolen painting worth over $100 million — and a big mystery, Washington Post