Bristol Jupiter

| Jupiter | |

|---|---|

| |

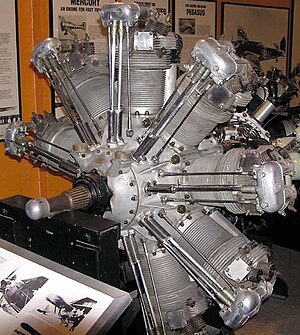

| Preserved Bristol Jupiter | |

| Type | Piston aircraft engine |

| Manufacturer | Bristol Aeroplane Company |

| Designed by | Roy Fedden |

| First run | 29 October 1918 |

Major applications | Bristol Bulldog Gloster Gamecock |

Number built | >7,100 |

Developed into | Bristol Mercury |

The Bristol Jupiter was a British nine-cylinder single-row piston radial engine built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company. Originally designed late in World War I and known as the Cosmos Jupiter, a lengthy series of upgrades and developments turned it into one of the finest engines of its era.

The Jupiter was widely used on many aircraft designs during the 1920s and 1930s. Thousands of Jupiters of all versions were produced, both by Bristol and abroad under licence.

A turbo-supercharged version of the Jupiter known as the Orion suffered development problems and only a small number were produced. The "Orion" name was later re-used by Bristol for an unrelated turboprop engine.

Contents

1 Design and development

1.1 Licensed production

2 Variants

3 Applications

3.1 Cosmos Jupiter

3.2 Bristol Jupiter

3.3 Gnome-Rhône Jupiter

3.4 Shvetsov M-22

4 Engines on display

5 Specifications (Jupiter XFA)

5.1 General characteristics

5.2 Components

5.3 Performance

6 See also

7 References

7.1 Bibliography

8 Further reading

9 External links

Design and development

The Jupiter was designed during World War I by Roy Fedden of Brazil Straker and later Cosmos Engineering. The first Jupiter was completed by Brazil Straker in 1918 and featured three carburettors, each one feeding three of the engine's nine cylinders via a spiral deflector housed inside the induction chamber.[1] During the rapid downscaling of military spending after the war, Cosmos Engineering became bankrupt in 1920, and was eventually purchased by the Bristol Aeroplane Company on the strengths of the Jupiter design and the encouragement of the Air Ministry.[2] The engine matured into one of the most reliable on the market. It was the first air-cooled engine to pass the Air Ministry full-throttle test, the first to be equipped with automatic boost control, and the first to be fitted to airliners.[3]

The Jupiter was fairly standard in design, but featured four valves per cylinder, which was uncommon at the time. The cylinders were machined from steel forgings, and the cast cylinder heads were later replaced with aluminium alloy following studies by the Royal Aircraft Establishment. In 1927, a change was made to move to a forged head design due to the rejection rate of the castings. The Jupiter VII introduced a mechanically-driven supercharger to the design, and the Jupiter VIII was the first to be fitted with reduction gears.[4]

In 1925, Fedden started designing a replacement for the Jupiter. Using a shorter stroke to increase the revolutions per minute (rpm), and including a supercharger for added power, resulted in the Bristol Mercury of 1927. Applying the same techniques to the original Jupiter-sized engine in 1927 resulted in the Bristol Pegasus. Neither engine would fully replace the Jupiter for a few years.

In 1926 a Jupiter-engined Bristol Bloodhound with the registration G-EBGG completed an endurance flight of 25,074 miles, during which the Jupiter ran for a total of 225 hours and 54 minutes without part failure or replacement.[5]

Licensed production

The Jupiter saw widespread use in licensed versions, with fourteen countries eventually producing the engine. In France, Gnome-Rhone produced a version known as the Gnome-Rhône 9 Jupiter that was used in several local civilian designs, as well as achieving some export success. Siemens-Halske took out a licence in Germany and produced several versions of increasing power, eventually resulting in the Bramo 323 Fafnir, which saw use in German wartime aircraft.[6]

In Japan, the Jupiter was license-built from 1924 by Nakajima, forming the basis of its own subsequent radial aero-engine design, the Nakajima Ha-1 Kotobuki.[7] It was produced in Poland as the PZL Bristol Jupiter, in Italy as the Alfa Romeo 126-RC35,[8] and in Czechoslovakia by Walter Engines. The most produced version was in the Soviet Union, where its Shvetsov M-22 version powered the initial Type 4 version of the Polikarpov I-16 (55 units produced). Type 4 Polikarpovs can be identified by their lack of exhaust stubs, rounded NACA cowling and lack of cowling shutters, features which were introduced on the Shvetsov M-25 powered Type 5 and later variants (total production 4,500+ units).[9][10] Production started in 1918 and ceased in 1930.

Variants

The Jupiter was produced in many variants, one of which was the Bristol Orion of 1926. Metallurgy problems with this turbo-supercharged engine caused the project to be abandoned after only nine engines had been built.[11]

- Brazil Straker (Cosmos) Jupiter I

- (1918) 400 hp (300 kW); only two engines assembled.

- Cosmos Jupiter II

- (1918) 400 hp (300 kW); a single engine assembled.

- Bristol Jupiter II

- (1923) 400 hp (300 kW).

- Bristol Jupiter III

- (1923) 400 hp (300 kW).

Bristol Jupiter VII on display at the Shuttleworth Collection.

- Bristol Jupiter IV

- (1926) 430 hp (320 kW); fitted with variable valve timing and a Bristol Triplex carburettor.

- Bristol Jupiter V

- (1925) 480 hp (360 kW).

- Bristol Jupiter VI

- (1927) 520 hp (390 kW); produced in both high- (6.3:1) and low- (5.3:1) compression ratio versions.

- Bristol Jupiter VIA

- (1927) 440 hp (330 kW); civil version of Jupiter VI.

- Bristol Jupiter VIFH

- (1932) 440 hp (330 kW); version of Jupiter VI equipped with gas starter motor.

- Bristol Jupiter VIFL

- (1932) 440 hp (330 kW); version of Jupiter VI with compression ratio of 5.15:1.

- Bristol Jupiter VIFM

- (1932) 440 hp (330 kW); version of Jupiter VI with compression ratio of 5.3:1.

- Bristol Jupiter VIFS

- (1932) 400 hp (300 kW); version of Jupiter VI with compression ratio of 6.3:1.

- Bristol Jupiter VII

- (1928) 375 hp (280 kW); fitted with supercharger, with compression ratio of 5.3:1; also manufactured by Gnome-Rhone as the 9ASB.

- Bristol Jupiter VIIF

- (1929) 480 hp (360 kW); version of Jupiter VII with forged cylinder heads.

Preserved Bristol Jupiter VIIIF

- Bristol Jupiter VIIFP

- (1930) 480 hp (360 kW); version of Jupiter VII with pressure feed lubrication to wrist-pins.

- Bristol Jupiter VIII

- (1929) 440 hp (330 kW); first version with propeller reduction gearing;[12] compression ratio 6.3:1.

- Bristol Jupiter VIIIF

- (1929) 460 hp (340 kW); version of Jupiter VIII with forged cylinder heads and lowered compression ratio (5.8:1).

- Bristol Jupiter VIIIFP

- (1929) 460 hp (340 kW); version of Jupiter VIII with pressure feed lubrication (time between overhauls at this stage in development was only 150 hours due to multiple failures).

- Bristol Jupiter IX

- 480 hp (360 kW); compression ratio 5.3:1.

- Bristol Jupiter IXF

- 550 hp (410 kW); version of Jupiter IX with forged cylinder heads

- Bristol Jupiter X

- 470 hp (350 kW); compression ratio 5.3:1.

- Bristol Jupiter XF

- 540 hp (400 kW); version of Jupiter X with forged cylinder heads

- Bristol Jupiter XFA

- 483 hp (360 kW)

- Bristol Jupiter XFAM

- 580 hp (430 kW)

- Bristol Jupiter XFBM

- 580 hp (430 kW)

- Bristol Jupiter XFS

- Fully supercharged.

- Bristol Jupiter XI

- Compression ratio 5.15:1.

- Bristol Jupiter XIF

- 500 hp (370 kW); compression ratio 5.15:1.

- Bristol Jupiter XIFA

- 480 hp (360 kW); version of Jupiter XIF with 0.656:1 propeller gear reduction ratio

- Bristol Jupiter XIFP

- 525 hp (391 kW); version of Jupiter XIF with pressure feed lubrication.

- Bristol Orion I

- (1926) Jupiter III, turbo-supercharged, abandoned programme.

- Gnome-Rhône 9A Jupiter

- French licence production primarily of 9A, 9Aa, 9Ab, 9Ac, 9Akx and 9Ad variants.

- Siemens-Halske Sh20, Sh21 and Sh22

- Siemens-Halske took out a licence in Germany and produced several versions of increasing power, eventually resulting in the Bramo 323 Fafnir, which saw use in wartime models.

- Nakajima Ha-1 Kotobuki

- In Japan, the Jupiter was licence-built from 1924 by Nakajima.

- PZL Bristol Jupiter

- Polish production.

- Alfa Romeo Jupiter

- Italian licence production, 420 hp (310 kW).

- Alfa 126 R.C.35

- Alfa Romeo developed variant

- Walter Jupiter

- Licence production in Czechoslovakia by Walter Engines

- Shvetsov M-22

- The most produced version; manufactured in the Soviet Union.

- IAM 9AD

- Licence production of the Gnome-Rhône 9A in Yugoslavia

Applications

The Jupiter is probably best known for powering the Handley Page H.P.42 airliners, which flew the London-Paris route in the 1930s. Other civilian uses included the de Havilland Giant Moth and de Havilland Hercules, the Junkers G 31 and the huge Dornier Do X flying boat, which used no less than twelve engines.

Military uses were less common, but included the parent company's Bristol Bulldog, as well as the Gloster Gamecock and Boulton Paul Sidestrand. It was also found in prototypes around the world, from Japan to Sweden.

By 1929 the Bristol Jupiter had flown in 262 different aircraft types,[13]it was noted in the French press at that year's Paris Air Show that the Jupiter and its license-built versions were powering 80% of the aircraft on display.[14][citation needed]

Note:[15]

Cosmos Jupiter

- Bristol Badger

- Bristol Bullet

- Sopwith Schneider

- Westland Limousine

Bristol Jupiter

- Aero A.32

- Airco DH.9

- Arado Ar 64

- Avia BH-25

- Avia BH-33E

- Bernard 190

- Blériot-SPAD 51

- Blériot-SPAD S.56

- Boulton & Paul Bugle

- Boulton Paul P.32

- Boulton Paul Partridge

- Boulton Paul Sidestrand

- Blackburn Beagle

- Blackburn Nile

- Blackburn Ripon

- Bristol Badger

- Bristol Badminton

- Bristol Bagshot

- Bristol Beaver

- Bristol Bloodhound

- Bristol Boarhound

- Bristol Brandon

- Bristol Bulldog

- Bristol Bullfinch

- Bristol Jupiter Fighter

- Bristol Seely

- Bristol Type 72

- Bristol Type 75

- Bristol Type 76

- Bristol Type 89

- Bristol Type 92

- Bristol Type 118

- de Havilland Dingo

- de Havilland DH.72

- de Havilland DH.50

- de Havilland Dormouse

- de Havilland Hercules

- de Havilland Hound

- de Havilland Giant Moth

- de Havilland Survey

- Dornier Do 11

- Dornier Do J

- Dornier Do X

- Fairey IIIF

- Fairey Ferret

- Fairey Flycatcher

- Fairey Hendon

- Fokker C.V

- Fokker F.VIIA

- Fokker F.VIII

- Fokker F.IX

- Gloster Gambet

- Gloster Gamecock

- Gloster Gnatsnapper

- Gloster Goldfinch

- Gloster Goral

- Gloster Goring

- Gloster Grebe

- Gloster Mars

- Gloster Survey

- Gourdou-Leseurre LGL.32

- Handley Page Clive

- Handley Page Hampstead

- Handley Page Hare

- Handley Page Hinaidi

- Handley Page HP.12

- Handley Page H.P.42

- Hawker Duiker

- Hawker Harrier

- Hawker Hart

- Hawker Hawfinch

- Hawker Hedgehog

- Hawker Heron

- Hawker Woodcock

- Junkers F.13

- Junkers G 31

- Junkers W 34

- Parnall Plover

- PZL P.7

- Saunders Medina

- Saunders Severn

- Short Calcutta

- Short Chamois

- Short Gurnard

- Short Kent

- Short Rangoon

- Short Scylla

- Short Springbok

- Short S.6 Sturgeon

- Short Valetta

- Supermarine Seagull

- Supermarine Solent

- Supermarine Southampton

- Svenska Aero Jaktfalken

- Tupolev I-4

- Vickers F.21/26

- Vickers F.29/27

- Vickers Jockey

- Vickers Type 143

- Vickers Type 150

- Vickers Valiant

- Vickers Vellore

- Vickers Vellox

- Vickers Vespa

- Vickers Viastra

- Vickers Victoria

- Vickers Vildebeest

- Vickers Vimy

- Vickers Vimy Trainer

- Vickers Wibault Scout

- Villiers 26

- Westland Interceptor

- Westland Wapiti

- Westland Westbury

- Westland Witch

- Westland-Houston PV.3

Gnome-Rhône Jupiter

- Bernard SIMB AB 12

- Blanchard BB-1

- Fizir F1M-Jupiter

- Latécoère 6

- Lioré et Olivier LeO H-15

- Potez 29/4

- Wibault Wib.220

- Denhaut Hy.479

Shvetsov M-22

- Kalinin K-5

- Polikarpov I-5

- Polikarpov I-15

- Polikarpov I-16

- Tupolev I-4

Yakovlev AIR-7[16]

Engines on display

- A Bristol Jupiter VI is on static display at Aerospace Bristol in the former Bristol Aeroplane Company factory complex in Filton, a suburb of Bristol, United Kingdom.[17]

- A Bristol Jupiter VIIF is on static display at the Shuttleworth Collection in Old Warden, United Kingdom.

- A Bristol Jupiter VIIIF is on static display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum at Washington Dulles International Airport in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States.[12]

- A Bristol Bulldog complete with a Jupiter VIIFP engine is on static display at the Royal Air Force Museum London in Hendon, United Kingdom.[18][19]

Specifications (Jupiter XFA)

Data from Lumsden[20]

General characteristics

Type: Nine-cylinder, naturally aspirated, air-cooled radial engine

Bore: 5.75 in (146 mm)

Stroke: 7.5 in (190 mm)

Displacement: 1,753 in3 (28.7 L)

Diameter: 54.5 in (1,384 mm)

Dry weight: 995 lb (451 kg)

Components

Valvetrain: Overhead poppet valve, four valves per cylinder, two intake and two exhaust

Supercharger: Single speed, single stage

Fuel type: 73-77 octane petrol

Cooling system: Air-cooled

Performance

Power output:- 550 hp (414 kW) at 2,200 rpm at 11,000 ft (3,350 m) - maximum power limited to five minutes operation.

- 525 hp (391 kW) at 2,000 rpm - maximum continuous power at 11,000 ft (3,350 m)

- 483 hp (360 kW) at 2,000 rpm - takeoff power

Specific power: 0.31 hp/in3 (14.4 kW/L)

Compression ratio: 5.3:1

Power-to-weight ratio: 0.55 hp/lb (0.92 kW/kg)

See also

Related development

- Alfa Romeo 125

- Bristol Mercury

- Bristol Pegasus

- Nakajima Kotobuki

- Siemens-Halske Sh 22

Comparable engines

- BMW 132

Pratt & Whitney R-1340, first of the famous Wasp radial engine line

Pratt & Whitney R-1690 Hornet

Wright R-1820 Cyclone 9

Related lists

- List of aircraft engines

References

^ Flight 9 March 1939, pp.236-237

^ Gunston 1989, p.44.

^ Gunston 1989, p.31.

^ Bridgman (Jane's) 1998, p.270.

^ http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1926/1926%20-%200183.html

^ Gunston 1989, p.29.

^ Gunston 1989, p.104.

^ "Alfa Aero Engines". aroca-qld.com. Archived from the original on 2007-10-08. Retrieved 2007-08-25..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ [1]

^ Gunston 1989, p.158.

^ Lumsden 2003, p.101.

^ ab "Bristol Jupiter VIIIF Radial Engine". National Air and Space Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

^ "The Bristol Jupiter Aircraft Engine". Air Power World. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

^ Gunston 2006, p.126.

^ British aircraft list from Lumsden, the Jupiter may not be the main powerplant for these types

^ OKB YAKOVLEV, Yefim Gordon, Dmitriy Komissarov, Sergey Komissarov, 2005, Midland Publishing pp 28-29

^ "Things to See and Do". Aerospace Bristol. Bristol Aero Collection Trust. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

^ "Bristol Bulldog MkIIA". rafmuseum.org. Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

^ "Individual History: Bristol Bulldog MkIIA G-ABBB/`K2227', Museum Accession Number 1994/1386/A" (PDF). rafmuseum.org. Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

^ Lumsden 2003, p.96.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

G. Geoffrey Smith, ed. (9 March 1939). "Rise of the Radials". Flight. XXXV (1576): 236–244. Retrieved 17 May 2018.- Bridgman, L. (ed.) Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. New York: Crescent Books, 1998.

ISBN 0-517-67964-7 - Lumsden, Alec. British Piston Engines and their Aircraft. Marlborough, Wiltshire: Airlife Publishing, 2003.

ISBN 1-85310-294-6. - Gunston, Bill. Development of Piston Aero Engines. Cambridge, England. Patrick Stephens Limited, 2006.

ISBN 0-7509-4478-1 - Gunston, Bill. World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines. Cambridge, England. Patrick Stephens Limited, 1989.

ISBN 1-85260-163-9

Further reading

- Gunston, Bill. By Jupiter! The Life of Sir Roy Fedden. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bristol Jupiter. |

"The Cosmos Aero Engines" (PDF). Flight. XI (27): 869–871. 3 July 1919. No. 549. Retrieved 12 January 2011. Contemporary article on Cosmos Engineering's air-cooled radial engines. Photos of the Cosmos Jupiter are on page 870, and a short technical description is on page 871.- Bristol Jupiter endurance test - Flight, March 1926

- A 1929 Flight advertisement for the Jupiter