Reciprocating engine

Internal combustion piston engine Components of a typical, four-stroke cycle, internal combustion piston engine.

- C. Crankshaft

- E. Exhaust camshaft

- I. Intake camshaft

- P. Piston

- R. Connecting rod

- S. Spark plug

- W. Water jacket for coolant flow

- V. Valves

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine (although there are also pneumatic and hydraulic reciprocating engines) that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common features of all types. The main types are: the internal combustion engine, used extensively in motor vehicles; the steam engine, the mainstay of the Industrial Revolution; and the niche application Stirling engine. Internal combustion engines are further classified in two ways: either a spark-ignition (SI) engine, where the spark plug initiates the combustion; or a compression-ignition (CI) engine, where the air within the cylinder is compressed, thus heating it, so that the heated air ignites fuel that is injected then or earlier.[1]

Contents

1 Common features in all types

2 History

3 Engine capacity

4 Other modern non-internal combustion types

5 Reciprocating quantum heat engine

6 Miscellaneous engines

7 See also

8 Notes

9 External links

Common features in all types

There may be one or more pistons. Each piston is inside a cylinder, into which a gas is introduced, either already under pressure (e.g. steam engine), or heated inside the cylinder either by ignition of a fuel air mixture (internal combustion engine) or by contact with a hot heat exchanger in the cylinder (Stirling engine). The hot gases expand, pushing the piston to the bottom of the cylinder. This position is also known as the Bottom Dead Center (BDC), or where the piston forms the largest volume in the cylinder. The piston is returned to the cylinder top (Top Dead Centre) (TDC) by a flywheel, the power from other pistons connected to the same shaft or (in a double acting cylinder) by the same process acting on the other side of the piston. This is where the piston forms the smallest volume in the cylinder. In most types the expanded or "exhausted" gases are removed from the cylinder by this stroke. The exception is the Stirling engine, which repeatedly heats and cools the same sealed quantity of gas. The stroke is simply the distance between the TDC and the BDC, or the greatest distance that the piston can travel in one direction.

In some designs the piston may be powered in both directions in the cylinder, in which case it is said to be double-acting.

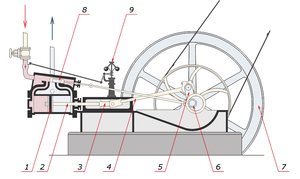

Steam piston engine

A labeled schematic diagram of a typical single-cylinder, simple expansion, double-acting high pressure steam engine. Power takeoff from the engine is by way of a belt.

- Piston

- Piston rod

- Crosshead bearing

- Connecting rod

- Crank

- Eccentric valve motion

- Flywheel

- Sliding valve

- Centrifugal governor

In most types, the linear movement of the piston is converted to a rotating movement via a connecting rod and a crankshaft or by a swashplate or other suitable mechanism. A flywheel is often used to ensure smooth rotation or to store energy to carry the engine through an un-powered part of the cycle. The more cylinders a reciprocating engine has, generally, the more vibration-free (smoothly) it can operate. The power of a reciprocating engine is proportional to the volume of the combined pistons' displacement.

A seal must be made between the sliding piston and the walls of the cylinder so that the high pressure gas above the piston does not leak past it and reduce the efficiency of the engine. This seal is usually provided by one or more piston rings. These are rings made of a hard metal, and are sprung into a circular groove in the piston head. The rings fit closely in the groove and press lightly against the cylinder wall to form a seal, and more heavily when higher combustion pressure moves around to their inner surfaces.

It is common to classify such engines by the number and alignment of cylinders and total volume of displacement of gas by the pistons moving in the cylinders usually measured in cubic centimetres (cm³ or cc) or litres (l) or (L) (US: liter). For example, for internal combustion engines, single and two-cylinder designs are common in smaller vehicles such as motorcycles, while automobiles typically have between four and eight, and locomotives, and ships may have a dozen cylinders or more. Cylinder capacities may range from 10 cm³ or less in model engines up to thousands of liters in ships' engines.[2]

The compression ratio affects the performance in most types of reciprocating engine. It is the ratio between the volume of the cylinder, when the piston is at the bottom of its stroke, and the volume when the piston is at the top of its stroke.

The bore/stroke ratio is the ratio of the diameter of the piston, or "bore", to the length of travel within the cylinder, or "stroke". If this is around 1 the engine is said to be "square", if it is greater than 1, i.e. the bore is larger than the stroke, it is "oversquare". If it is less than 1, i.e. the stroke is larger than the bore, it is "undersquare".

Cylinders may be aligned in line, in a V configuration, horizontally opposite each other, or radially around the crankshaft. Opposed-piston engines put two pistons working at opposite ends of the same cylinder and this has been extended into triangular arrangements such as the Napier Deltic. Some designs have set the cylinders in motion around the shaft, such as the Rotary engine.

Stirling piston engine Rhombic Drive – Beta Stirling Engine Design, showing the second displacer piston (green) within the cylinder, which shunts the working gas between the hot and cold ends, but produces no power itself.

Hot cylinder wall

Cold cylinder wall

Displacer piston

Power piston

Flywheels

In steam engines and internal combustion engines, valves are required to allow the entry and exit of gases at the correct times in the piston's cycle. These are worked by cams, eccentrics or cranks driven by the shaft of the engine. Early designs used the D slide valve but this has been largely superseded by Piston valve or Poppet valve designs. In steam engines the point in the piston cycle at which the steam inlet valve closes is called the cutoff and this can often be controlled to adjust the torque supplied by the engine and improve efficiency. In some steam engines, the action of the valves can be replaced by an oscillating cylinder.

Internal combustion engines operate through a sequence of strokes that admit and remove gases to and from the cylinder. These operations are repeated cyclically and an engine is said to be 2-stroke, 4-stroke or 6-stroke depending on the number of strokes it takes to complete a cycle.

In some steam engines, the cylinders may be of varying size with the smallest bore cylinder working the highest pressure steam. This is then fed through one or more, increasingly larger bore cylinders successively, to extract power from the steam at increasingly lower pressures. These engines are called Compound engines.

Aside from looking at the power that the engine can produce, the Mean Effective Pressure (MEP), can also be used in comparing the power output and performance of reciprocating engines of the same size. The mean effective pressure is the fictitious pressure which would produce the same amount of net work that was produced during the power stroke cycle. This is shown by:

- Wnet = MEP × Piston Area × Stroke = MEP × Displacement Volume

and therefore:

- MEP = Wnet / Displacement Volume

Whichever engine with the larger value of MEP produces more net work per cycle and performs more efficiently.[1]

History

An early known example of rotary to reciprocating motion is the crank mechanism. The earliest hand-operated cranks appeared in China during the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD).[3] Several saw mills in Roman Asia and Byzantine Syria during the 3rd–6th centuries AD had a crank and connecting rod mechanism which converted the rotary motion of a water wheel into the linear movement of saw blades.[4] In 1206, Arab engineer Al-Jazari invented a crankshaft.[5]

The reciprocating engine developed in Europe during the 18th century, first as the atmospheric engine then later as the steam engine. These were followed by the Stirling engine and internal combustion engine in the 19th century. Today the most common form of reciprocating engine is the internal combustion engine running on the combustion of petrol, diesel, Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) or compressed natural gas (CNG) and used to power motor vehicles and engine power plants.

One notable reciprocating engine from the World War II Era was the 28-cylinder, 3,500 hp (2,600 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-4360 "Wasp Major" radial engine. It powered the last generation of large piston-engined planes before jet engines and turboprops took over from 1944 onward. It had a total engine capacity of 71.5 L (4,360 cu in), and a high power-to-weight ratio.

The largest reciprocating engine in production at present, but not the largest ever built, is the Wärtsilä-Sulzer RTA96-C turbocharged two-stroke diesel engine of 2006 built by Wärtsilä. It is used to power the largest modern container ships such as the Emma Mærsk. It is five stories high (13.5 m or 44 ft), 27 m (89 ft) long, and weighs over 2,300 metric tons (2,500 short tons) in its largest 14 cylinders version producing more than 84.42 MW (114,800 bhp). Each cylinder has a capacity of 1,820 L (64 cu ft), making a total capacity of 25,480 L (900 cu ft) for the largest versions.

Engine capacity

For piston engines, an engine's capacity is the engine displacement, in other words the volume swept by all the pistons of an engine in a single movement. It is generally measured in litres (l) or cubic inches (c.i.d., cu in, or in³) for larger engines, and cubic centimetres (abbreviated cc) for smaller engines. All else being equal, engines with greater capacities are more powerful and consumption of fuel increases accordingly (although this is not true of every Reciprocating engine), although power and fuel consumption are affected by many factors outside of engine displacement.

Other modern non-internal combustion types

Reciprocating engines that are powered by compressed air, steam or other hot gases are still used in some applications such as to drive many modern torpedoes or as pollution-free motive power. Most steam-driven applications use steam turbines, which are more efficient than piston engines.

The French-designed FlowAIR vehicles use compressed air stored in a cylinder to drive a reciprocating engine in a local-pollution-free urban vehicle.[6]

Torpedoes may use a working gas produced by high test peroxide or Otto fuel II, which pressurise without combustion. The 230 kg (510 lb) Mark 46 torpedo, for example, can travel 11 km (6.8 mi) underwater at 74 km/h (46 mph) fuelled by Otto fuel without oxidant.

Reciprocating quantum heat engine

Quantum heat engines are devices that generate power from heat that flows from a hot to a cold reservoir.

The mechanism of operation of the engine can be described by the laws of quantum mechanics.

Quantum refrigerators are devices that consume power with the purpose to pump heat from a cold to a hot reservoir.

In a reciprocating quantum heat engine, the working medium is a quantum system such as spin systems or a harmonic oscillator.

The Carnot cycle and Otto cycle are the ones most studied.[7]

The quantum versions obey the laws of thermodynamics. In addition, these models can justify the assumptions of

endoreversible thermodynamics.

A theoretical study has shown that it is possible and practical to build a reciprocating engine that is composed of a single oscillating atom. This is an area for future research and could have applications in nanotechnology.[8]

Miscellaneous engines

There are a large number of unusual varieties of piston engines that have various claimed advantages, many of which see little if any current use:

- Free-piston engine

- Opposed-piston engine

- Swing-piston engine

- IRIS engine

- Bourke engine

- Thermo-magnetic motor

See also

Heat engine for a view of the thermodynamics involved in these engines.- For a contrasting approach using no pistons, see the pistonless rotary engine.

- For an historical perspective see Timeline of heat engine technology.

Steam engine- Steam locomotive

- Stirling engine

Internal combustion engine- Otto cycle

- Diesel cycle

Engine configuration for a discussion of the layout of the major components of a reciprocating piston internal combustion engine.- Diesel engine

- Gasoline engine

Notes

^ ab Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach by Yunus A. Cengal and Michael A. Boles

^ Hanlon, Mike. Most powerful diesel engine in the world GizMag. Accessed: 14 April 2017.

^ Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Pages 118–119.

^ Ritti, Tullia; Grewe, Klaus; Kessener, Paul (2007), "A Relief of a Water-powered Stone Saw Mill on a Sarcophagus at Hierapolis and its Implications", Journal of Roman Archaeology, 20: 138–163.mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Sally Ganchy, Sarah Gancher (2009), Islam and Science, Medicine, and Technology, The Rosen Publishing Group, p. 41, ISBN 1-4358-5066-1

^ AIRPod manufactured by MDI SA. Accessed February 19, 2015

^ [1] Irreversible performance of a quantum harmonic heat engine, Rezek and Kosloff, New J. Phys. 8 (2006) 83

^ Can a car engine be built out of a single particle? Physorg, November 30, 2012 by Lisa Zyga. Accessed 01-12-12

External links

Combustion video - in-cylinder combustion in an optically accessible, 2-stroke engine- HowStuffWorks: How Car Engines Work

Reciprocating Engines at Infoplease.

Piston Engines at the US Centennial of Flight Commission.