Fossil fuel

Coal, one of the fossil fuels

A fossil fuel is a fuel formed by natural processes, such as anaerobic decomposition of buried dead organisms, containing energy originating in ancient photosynthesis.[1]

The age of the organisms and their resulting fossil fuels is typically millions of years, and sometimes exceeds 650 million years.[2]

Fossil fuels contain high percentages of carbon and include petroleum, coal, and natural gas.[3]

Other commonly used derivatives include kerosene and propane.

Fossil fuels range from volatile materials with low carbon to hydrogen ratios like methane, to liquids like petroleum, to nonvolatile materials composed of almost pure carbon, like anthracite coal.

Methane can be found in hydrocarbon fields either alone, associated with oil, or in the form of methane clathrates.

The theory that fossil fuels formed from the fossilized remains of dead plants by exposure to heat and pressure in the Earth's crust over millions of years was first introduced by Andreas Libavius “in his 1597 Alchemia [Alchymia]” and later by Mikhail Lomonosov “as early as 1757 and certainly by 1763”.[4]. The first use of the term "fossil fuel" was by the German chemist Caspar Neumann, in English translation in 1759.[5]

The United States Energy Information Administration estimates that in 2007 the world's primary energy sources consisted of petroleum (36.0%), coal (27.4%), natural gas (23.0%), amounting to an 86.4% share for fossil fuels in primary energy consumption in the world.[6]

Non-fossil sources in 2006 included nuclear (8.5%), hydroelectric (6.3%), and others (geothermal, solar, tidal, wind, wood, waste) amounting to 0.9%.[7]

World energy consumption was growing at about 2.3% per year.

Although fossil fuels are continually being formed via natural processes, they are generally considered to be non-renewable resources because they take millions of years to form and the known viable reserves are being depleted much faster than new ones are being made.[8][9]

The use of fossil fuels raises serious environmental concerns.

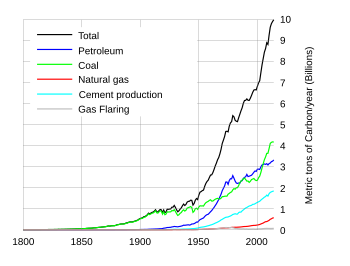

The burning of fossil fuels produces around 21.3 billion tonnes (21.3 gigatonnes) of carbon dioxide (CO2) per year.

It is estimated that natural processes can only absorb about half of that amount, so there is a net increase of 10.65 billion tonnes of atmospheric carbon dioxide per year.[10]

Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas that increases radiative forcing and contributes to global warming.

A global movement towards the generation of low-carbon renewable energy is underway to help reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

Contents

1 Origin

2 Importance

2.1 Reserves

3 Limits and alternatives

4 Environmental effects

5 Industry

5.1 Economic effects

6 See also

7 Footnotes

8 Further reading

9 External links

Origin

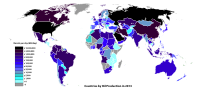

Since oil fields are located only at certain places on earth,[11] only some countries are oil-independent; the other countries depend on the oil-production capacities of these countries

Aquatic phytoplankton and zooplankton that died and sedimented in large quantities under anoxic conditions millions of years ago began forming petroleum and natural gas as a result of anaerobic decomposition. Over geological time this organic matter, mixed with mud, became buried under further heavy layers of inorganic sediment. The resulting high levels of heat and pressure caused the organic matter to chemically alter, first into a waxy material known as kerogen which is found in oil shales, and then with more heat into liquid and gaseous hydrocarbons in a process known as catagenesis. Despite these heat driven transformations (which may increase the energy density compared to typical organic matter), the embedded energy is still photosynthetic in origin.[1]

Terrestrial plants, on the other hand, tended to form coal and methane. Many of the coal fields date to the Carboniferous period of Earth's history. Terrestrial plants also form type III kerogen, a source of natural gas.

There is a wide range of organic, or hydrocarbon, compounds in any given fuel mixture. The specific mixture of hydrocarbons gives a fuel its characteristic properties, such as boiling point, melting point, density, viscosity, etc. Some fuels like natural gas, for instance, contain only very low boiling, gaseous components. Others such as gasoline or diesel contain much higher boiling components.

Importance

A petrochemical refinery in Grangemouth, Scotland, UK

Fossil fuels are of great importance because they can be burned (oxidized to carbon dioxide and water), producing significant amounts of energy per unit mass. The use of coal as a fuel predates recorded history. Coal was used to run furnaces for the melting of metal ore. Semi-solid hydrocarbons from seeps were also burned in ancient times,[12] but these materials were mostly used for waterproofing and embalming.[13]

Commercial exploitation of petroleum began in the 19th century, largely to replace oils from animal sources (notably whale oil) for use in oil lamps.[14]

Natural gas, once flared-off as an unneeded byproduct of petroleum production, is now considered a very valuable resource.[15] Natural gas deposits are also the main source of the element helium.

Heavy crude oil, which is much more viscous than conventional crude oil, and tar sands, where bitumen is found mixed with sand and clay, began to become more important as sources of fossil fuel as of the early 2000s.[16]Oil shale and similar materials are sedimentary rocks containing kerogen, a complex mixture of high-molecular weight organic compounds, which yield synthetic crude oil when heated (pyrolyzed). These materials had yet to be fully exploited commercially.[17] With additional processing, they can be employed in lieu of other already established fossil fuel deposits. More recently, there has been disinvestment from exploitation of such resources due to their high carbon cost, relative to more easily processed reserves.[18]

Prior to the latter half of the 18th century, windmills and watermills provided the energy needed for industry such as milling flour, sawing wood or pumping water, and burning wood or peat provided domestic heat. The widescale use of fossil fuels, coal at first and petroleum later, to fire steam engines enabled the Industrial Revolution. At the same time, gas lights using natural gas or coal gas were coming into wide use. The invention of the internal combustion engine and its use in automobiles and trucks greatly increased the demand for gasoline and diesel oil, both made from fossil fuels. Other forms of transportation, railways and aircraft, also required fossil fuels. The other major use for fossil fuels is in generating electricity and as feedstock for the petrochemical industry. Tar, a leftover of petroleum extraction, is used in construction of roads.

Reserves

An oil well in the Gulf of Mexico

Levels of primary energy sources are the reserves in the ground. Flows are production of fossil fuels from these reserves. The most important part of primary energy sources are the carbon based fossil energy sources. Coal, oil, and natural gas provided 79.6% of primary energy production during 2002 (in million tonnes of oil equivalent (mtoe)) (34.9+23.5+21.2).

Levels (proved reserves) during 2005–2006

- Coal: 997,748 million short tonnes (905 billion metric tonnes),[19] 4,416 billion barrels (702.1 km3) of oil equivalent

- Oil: 1,119 billion barrels (177.9 km3) to 1,317 billion barrels (209.4 km3)[20]

- Natural gas: 6,183–6,381 trillion cubic feet (175–181 trillion cubic metres),[20] 1,161 billion barrels (184.6×10

^9 m3) of oil equivalent

Flows (daily production) during 2006

- Coal: 18,476,127 short tonnes (16,761,260 metric tonnes),[21] 52,000,000 barrels (8,300,000 m3) of oil equivalent per day

- Oil: 84,000,000 barrels per day (13,400,000 m3/d)[22]

- Natural gas: 104,435 billion cubic feet (2,963 billion cubic metres),[23] 19,000,000 barrels (3,000,000 m3) of oil equivalent per day

Limits and alternatives

P. E. Hodgson, a senior research fellow emeritus in physics at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, expects the world energy use is doubling every fourteen years and the need is increasing faster still and he insisted in 2008 that the world oil production, a main resource of fossil fuel, is expected to peak in ten years and thereafter fall.[24]

The principle of supply and demand holds that as hydrocarbon supplies diminish, prices will rise. Therefore, higher prices will lead to increased alternative, renewable energy supplies as previously uneconomic sources become sufficiently economical to exploit. Artificial gasolines and other renewable energy sources currently require more expensive production and processing technologies than conventional petroleum reserves, but may become economically viable in the near future.

Different alternative sources of energy include nuclear, hydroelectric, solar, wind, and geothermal.

One of the more promising energy alternatives is the use of inedible feed stocks and biomass for carbon dioxide capture as well as biofuel. While these processes are not without problems, they are currently in practice around the world. Biodiesels are being produced by several companies and source of great research at several universities. Some of the most common and promising processes of conversion of renewable lipids into usable fuels is through hydrotreating and decarboxylation.

Environmental effects

Global fossil carbon emission by fuel type, 1800–2007. Note: Carbon only represents 27% of the mass of CO2

The United States holds less than 5% of the world's population, but due to large houses and private cars, uses more than 25% of the world's supply of fossil fuels.[25] As the largest source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, CO2 from fossil fuel combustion, accounted for 80 percent of [its] weighted emissions in 1998.[26] Combustion of fossil fuels also produces other air pollutants, such as nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, volatile organic compounds and heavy metals.

According to Environment Canada:

"The electricity sector is unique among industrial sectors in its very large contribution to emissions associated with nearly all air issues. Electricity generation produces a large share of Canadian nitrogen oxides and sulphur dioxide emissions, which contribute to smog and acid rain and the formation of fine particulate matter. It is the largest uncontrolled industrial source of mercury emissions in Canada. Fossil fuel-fired electric power plants also emit carbon dioxide, which may contribute to climate change. In addition, the sector has significant impacts on water and habitat and species. In particular, hydropower dams and transmission lines have significant effects on water and biodiversity."[27]

Carbon dioxide variations over the last 400,000 years, showing a rise since the industrial revolution

According to U.S. Scientist Jerry Mahlman and USA Today: Mahlman, who crafted the IPCC language used to define levels of scientific certainty, says the new report will lay the blame at the feet of fossil fuels with "virtual certainty," meaning 99% sure. That's a significant jump from "likely," or 66% sure, in the group's last report in 2001, Mahlman says. His role in this year's effort involved spending two months reviewing the more than 1,600 pages of research that went into the new assessment.[28]

Combustion of fossil fuels generates sulfuric, carbonic, and nitric acids, which fall to Earth as acid rain, impacting both natural areas and the built environment. Monuments and sculptures made from marble and limestone are particularly vulnerable, as the acids dissolve calcium carbonate.

Fossil fuels also contain radioactive materials, mainly uranium and thorium, which are released into the atmosphere. In 2000, about 12,000 tonnes of thorium and 5,000 tonnes of uranium were released worldwide from burning coal.[29] It is estimated that during 1982, US coal burning released 155 times as much radioactivity into the atmosphere as the Three Mile Island accident.[30]

Burning coal also generates large amounts of bottom ash and fly ash. These materials are used in a wide variety of applications, utilizing, for example, about 40% of the US production.[31]

Harvesting, processing, and distributing fossil fuels can also create environmental concerns. Coal mining methods, particularly mountaintop removal and strip mining, have negative environmental impacts, and offshore oil drilling poses a hazard to aquatic organisms. Oil refineries also have negative environmental impacts, including air and water pollution. Transportation of coal requires the use of diesel-powered locomotives, while crude oil is typically transported by tanker ships, each of which requires the combustion of additional fossil fuels.

Environmental regulation uses a variety of approaches to limit these emissions, such as command-and-control (which mandates the amount of pollution or the technology used), economic incentives, or voluntary programs.

An example of such regulation in the USA is the "EPA is implementing policies to reduce airborne mercury emissions. Under regulations issued in 2005, coal-fired power plants will need to reduce their emissions by 70 percent by 2018.".[32]

In economic terms, pollution from fossil fuels is regarded as a negative externality. Taxation is considered one way to make societal costs explicit, in order to 'internalize' the cost of pollution. This aims to make fossil fuels more expensive, thereby reducing their use and the amount of pollution associated with them, along with raising the funds necessary to counteract these factors.[citation needed]

According to Rodman D. Griffin, "The burning of coal and oil have saved inestimable amounts of time and labor while substantially raising living standards around the world".[33] Although the use of fossil fuels may seem beneficial to our lives, this act is playing a role on global warming and it is said to be dangerous for the future.[33]

Moreover, these environmental pollutions impacts on the human beings because its particles of the fossil fuel on the air cause negative health effects when inhaled by people. These health effects include premature death, acute respiratory illness, aggravated asthma, chronic bronchitis and decreased lung function. So, the poor, undernourished, very young and very old, and people with preexisting respiratory disease and other ill health, are more at risk.[34]

Industry

Economic effects

Europe spent €406 billion on importing fossil fuels in 2011 and €545 billion in 2012. This is around three times more than the cost of the Greek bailout up to 2013. In 2012 wind energy in Europe avoided €9.6 billion of fossil fuel costs.[35] A 2014 report by the International Energy Agency said that the fossil fuels industry collects $550 billion a year in global government fossil fuel subsidies.[36] This amount was $490 billion in 2014, but would have been $610 billion without agreements made in 2009.[37]

A 2015 report studied 20 fossil fuel companies and found that, while highly profitable, the hidden economic cost to society was also large.[38][39] The report spans the period 2008–2012 and notes that: "For all companies and all years, the economic cost to society of their CO2 emissions was greater than their after‐tax profit, with the single exception of ExxonMobil in 2008."[38]:4 Pure coal companies fare even worse: "the economic cost to society exceeds total revenue in all years, with this cost varying between nearly $2 and nearly $9 per $1 of revenue."[38]:5 In this case, total revenue includes "employment, taxes, supply purchases, and indirect employment."[38]:4

See also

Abiogenic petroleum origin proposes that petroleum is not a fossil fuel- Bioremediation

- Carbon bubble

- Environmental impact of the energy industry

- Fossil Fools Day

- Fossil Fuel Beta

- Fossil fuel divestment

- Fossil fuel drilling

- Fossil fuel exporters

- Fossil fuel phase-out

- Fossil fuels lobby

- Hydraulic fracturing

- Liquefied petroleum gas

- Low-carbon power

- Peak coal

- Peak gas

- Petroleum industry

- Shale gas

- Oil shale

Footnotes

^ ab "thermochemistry of fossil fuel formation" (PDF)..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Paul Mann, Lisa Gahagan, and Mark B. Gordon, "Tectonic setting of the world's giant oil and gas fields," in Michel T. Halbouty (ed.) Giant Oil and Gas Fields of the Decade, 1990–1999, Tulsa, Okla.: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, p. 50, accessed 22 June 2009.

^ "Fossil fuel". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 2012-05-10.

^ Hsu, Chang Samuel; Robinson, Paul R. (2017). Springer Handbook of Petroleum Technology (2nd, illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 360. ISBN 978-3-319-49347-3.

Extract of page 360

^ Caspar Neumann; William Lewis (1759). The Chemical Works of Caspar Neumann ... (1773 printing). J. and F. Rivington. pp. 492–.

^ "U.S. EIA International Energy Statistics". Retrieved 2010-01-12.

^ "International Energy Annual 2006". Archived from the original on 2009-02-05. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

^ Miller, G.; Spoolman, Scott (28 September 2007). "Environmental Science: Problems, Connections and Solutions". Cengage Learning. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via Google Books.

^ Ahuja, Satinder (25 January 2015). "Food, Energy, and Water: The Chemistry Connection". Elsevier. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via Google Books.

^ "What Are Greenhouse Gases?". US Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

^ Oil fields map Archived 2012-08-06 at the Wayback Machine.. quakeinfo.ucsd.edu

^ "Encyclopædia Britannica, use of oil seeps in ancient times". Retrieved 2007-09-09.

^ Bilkadi, Zayn (1992). "BULLS FROM THE SEA : Ancient Oil Industries". Aramco World. Archived from the original on 2007-11-13.

^ Ball, Max W.; Douglas Ball; Daniel S. Turner (1965). This Fascinating Oil Business. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. ISBN 0-672-50829-X.

^ Kaldany, Rashad, Director Oil, Gas, Mining and Chemicals Dept, World Bank (December 13, 2006). Global Gas Flaring Reduction: A Time for Action! (PDF). Global Forum on Flaring & Gas Utilization. Paris. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

^ "Oil Sands Global Market Potential 2007". Retrieved 2007-09-09.

^ "US Department of Energy plans for oil shale development". Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

^ "Insurance giant Axa dumps investments in tar sands pipelines". Retrieved 2017-12-24.

^ World Estimated Recoverable Coal Archived 2008-09-20 at the Wayback Machine.. eia.doe.gov. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

^ ab World Proved Reserves of Oil and Natural Gas, Most Recent Estimates Archived 2011-05-23 at the Wayback Machine.. eia.doe.gov. Retrieved on 2012-01-27.

^ Energy Information Administration. International Energy Annual 2006 Archived 2008-09-22 at the Wayback Machine. (XLS file). October 17, 2008. eia.doe.gov

^ Energy Information Administration. World Petroleum Consumption, Annual Estimates, 1980–2008 (XLS file). October 6, 2009. eia.doe.gov

^ Energy Information Administration. International Energy Annual 2006 Archived 2008-09-25 at the Wayback Machine. (XLS file). August 22, 2008. eia.doe.gov

^ Hodgson, P.E (2008). "Nuclear Power and Energy Crisis". Modern Age. 50 (3): 238.

^ "The State of Consumption Today". Worldwatch Institute. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

^ Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–1998, Rep. EPA 236-R-00-01. US EPA, Washington, DC|accessdate=2017-12-24

^ "Electricity Generation". Environment Canada. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

^ O'Driscoll, Patrick; Vergano, Dan (2007-03-01). "Fossil fuels are to blame, world scientists conclude". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

^ Coal Combustion: Nuclear Resource or Danger Archived February 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. – Alex Gabbard

^ Nuclear proliferation through coal burning Archived 2009-03-27 at the Wayback Machine. – Gordon J. Aubrecht, II, Ohio State University

^ American Coal Ash Association. "CCP Production and Use Survey" (PDF).

[permanent dead link]

^ "Frequently Asked Questions, Information on Proper Disposal of Compact Fluorescent Light Bulbs (CFLs)" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-03-19.

^ ab Griffin, Rodman (10 July 1992). "Alternative Energy". 2 (2): 573–596.

^ Liodakis, E; Dashdorj, Dugersuren; Mitchell, Gary E. (2011). "The nuclear alternative". Energy Production within Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. AIP Conference Proceedings. 1342 (1): 91. doi:10.1063/1.3583174.

^ Avoiding fossil fuel costs with wind energy EWEA March 2014

^ Jerry Hirsch (2 June 2015). "Elon Musk: 'If I cared about subsidies, I would have entered the oil and gas industry'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

^ "World Energy Outlook" (PDF). www.worldenergyoutlook.org.

^ abcd

Hope, Chris; Gilding, Paul; Alvarez, Jimena (2015). Quantifying the implicit climate subsidy received by leading fossil fuel companies — Working Paper No. 02/2015 (PDF). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2016-06-27.

^

"Measuring fossil fuel 'hidden' costs". University of Cambridge Judge Business School. 23 July 2015. Retrieved 2016-06-27.

Further reading

- Ross Barrett and Daniel Worden (eds.), Oil Culture. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

- Bob Johnson, Carbon Nation: Fossil Fuels in the Making of American Culture. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2014.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fossil fuel |

Listen to this article (info/dl)

"The Coming Energy Crisis?" – essay by James L. Williams of WTRG Economics and A. F. Alhajji of Ohio Northern University

"Powering the Future" – Michael Parfit (National Geographic)- "Federal Fossil Fuel Subsidies and Greenhouse Gas Emissions"

- Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Europe

- Oil companies hit by 'state' cyber attacks

Debate

The Origin of Methane (and Oil) in the Crust of the Earth – Thomas Gold (Internet Archives)- Abiotic theory debunked "fossil fuel" myth