Martin Luther King Jr.

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Martin Luther King Jr. | |

|---|---|

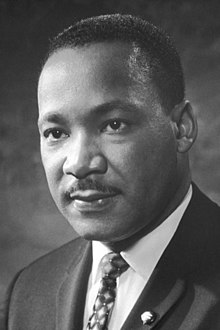

King in 1964 | |

| 1st President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference | |

In office January 10, 1957 – April 4, 1968 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Ralph Abernathy |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1929-01-15)January 15, 1929 Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | April 4, 1968(1968-04-04) (aged 39) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse(s) | Coretta Scott (m. 1953) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Civil rights movement, Peace movement |

| Awards |

|

| Monuments | Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial |

| Signature | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Campaigns

Death and memorial

| ||

Martin Luther King Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist who became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the civil rights movement from 1954 until his death in 1968. Born in Atlanta, King is best known for advancing civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, tactics his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi helped inspire.

King led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and in 1957 became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). With the SCLC, he led an unsuccessful 1962 struggle against segregation in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. He also helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech.

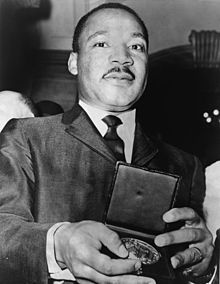

On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequality through nonviolent resistance.[1] In 1965, he helped organize the Selma to Montgomery marches. The following year, he and the SCLC took the movement north to Chicago to work on segregated housing. In his final years, he expanded his focus to include opposition towards poverty and the Vietnam War. He alienated many of his liberal allies with a 1967 speech titled "Beyond Vietnam". J. Edgar Hoover considered him a radical and made him an object of the FBI's COINTELPRO from 1963 on. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital liaisons and reported on them to government officials, and on one occasion mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.

In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the Poor People's Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. His death was followed by riots in many U.S. cities. Allegations that James Earl Ray, the man convicted and imprisoned of killing King, had been framed or acted in concert with government agents persisted for decades after the shooting. Sentenced to 99 years in prison for King's murder, effectively a life sentence as Ray was 41 at the time of conviction, Ray served 29 years of his sentence and died from hepatitis in 1998 while in prison.

King was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. Martin Luther King Jr. Day was established as a holiday in numerous cities and states beginning in 1971; the holiday was enacted at the federal level by legislation signed by President Ronald Reagan in 1986. Hundreds of streets in the U.S. have been renamed in his honor, and a county in Washington State was also rededicated for him. The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 2011.

Contents

1 Early life and education

1.1 Morehouse College

1.2 Crozer Theological Seminary

1.3 Doctoral studies

2 Montgomery bus boycott, 1955

3 Southern Christian Leadership Conference

3.1 Albany Movement, 1961

3.2 Birmingham campaign, 1963

3.3 St. Augustine, Florida, 1964

3.4 Selma, Alabama, 1964

3.5 New York City, 1964

4 March on Washington, 1963

5 Selma voting rights movement and "Bloody Sunday", 1965

6 Chicago open housing movement, 1966

7 Opposition to the Vietnam War

8 Poor People's Campaign, 1968

8.1 After King's death

9 Assassination and aftermath

9.1 Aftermath

9.2 Allegations of conspiracy

10 Legacy

10.1 Martin Luther King Jr. Day

10.2 Liturgical commemorations

10.3 UK legacy and The Martin Luther King Peace Committee

11 Ideas, influences, and political stances

11.1 Religion

11.2 Nonviolence

11.3 Politics

11.4 Compensation

11.5 Family planning

12 FBI and King's personal life

12.1 FBI surveillance and wiretapping

12.2 NSA monitoring of King's communications

12.3 Allegations of communism

12.4 CIA surveillance

12.5 Adultery

12.6 Police observation during the assassination

13 Awards and recognition

13.1 Five-dollar bill

14 Works

15 See also

16 References

16.1 Notes

16.2 Citations

16.3 Sources

16.4 Further reading

17 External links

Early life and education

The high school that King attended was named after African-American educator Booker T. Washington.

King was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to the Reverend Martin Luther King Sr. and Alberta Williams King.[2] King's legal name at birth was Michael King, and his father was also born Michael King, but, after a period of gradual transition on the elder King's part, he changed both his and his son's names in 1934.[3][4] The elder King would later state that "Michael" was a mistake by the attending physician to his son's birth,[5] and the younger King's birth certificate was altered to read "Martin Luther King Jr." in 1957.[6] King's parents were both African-American, and he also had Irish ancestry through his paternal great-grandfather.[7][8][9]

King was a middle child, between older sister Christine King Farris and younger brother A.D. King.[10] King sang with his church choir at the 1939 Atlanta premiere of the movie Gone with the Wind,[11] and he enjoyed singing and music. His mother was an accomplished organist and choir leader who took him to various churches to sing, and he received attention for singing "I Want to Be More and More Like Jesus". King later became a member of the junior choir in his church.[12]

King said that his father regularly whipped him until he was 15; a neighbor reported hearing the elder King telling his son "he would make something of him even if he had to beat him to death." King saw his father's proud and fearless protests against segregation, such as King Sr. refusing to listen to a traffic policeman after being referred to as "boy," or stalking out of a store with his son when being told by a shoe clerk that they would have to "move to the rear" of the store to be served.[13]

When King was a child, he befriended a white boy whose father owned a business near his family's home. When the boys were six, they started school: King had to attend a school for African Americans and the other boy went to one for whites (public schools were among the facilities segregated by state law). King lost his friend because the child's father no longer wanted the boys to play together.[14]

King suffered from depression through much of his life. In his adolescent years, he initially felt resentment against whites due to the "racial humiliation" that he, his family, and his neighbors often had to endure in the segregated South.[15] At the age of 12, shortly after his maternal grandmother died, King blamed himself and jumped out of a second-story window, but survived.[16]

King was initially skeptical of many of Christianity's claims. At the age of 13, he denied the bodily resurrection of Jesus during Sunday school.[17] From this point, he stated, "doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly."[18][17] However, he later concluded that the Bible has "many profound truths which one cannot escape" and decided to enter the seminary.[17]

Growing up in Atlanta, King attended Booker T. Washington High School. He became known for his public-speaking ability and was part of the school's debate team.[19] When King was 13 years old, in 1942, he became the youngest assistant manager of a newspaper delivery station for the Atlanta Journal.[20] During his junior year, he won first prize in an oratorical contest sponsored by the Negro Elks Club in Dublin, Georgia. On the ride home to Atlanta by bus, he and his teacher were ordered by the driver to stand so that white passengers could sit down. King initially refused but complied after his teacher told him that he would be breaking the law if he did not submit. During this incident, King said that he was "the angriest I have ever been in my life."[19] An outstanding student, he skipped both the ninth and the twelfth grades of high school.[21]

Morehouse College

During King's junior year in high school, Morehouse College—a respected historically black college—announced that it would accept any high school juniors who could pass its entrance exam. At that time, many students had abandoned further studies to enlist in World War II. Due to this, Morehouse was eager to fill its classrooms. At the age of 15, King passed the exam and entered Morehouse.[19] The summer before his last year at Morehouse, in 1947, the 18-year-old King chose to enter the ministry. He had concluded that the church offered the most assuring way to answer "an inner urge to serve humanity." King's "inner urge" had begun developing, and he made peace with the Baptist Church, as he believed he would be a "rational" minister with sermons that were "a respectful force for ideas, even social protest."[22]

Crozer Theological Seminary

In 1948, King graduated at the age of 19 from Morehouse with a B.A. in sociology. He then enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with a B.Div. degree in 1951.[23][24] King's father fully supported his decision to continue his education and made arrangements for King to work with J. Pius Barbour, a family friend who pastored at Calvary Baptist Church in Chester.[25] King became known as one of the "Sons of Calvary", an honor he shared with William Augustus Jones, Jr. and Samuel D. Proctor who went on to become well-known preachers in the black church.[26]

While attending Crozer, King was joined by Walter McCall, a former classmate at Morehouse.[27] At Crozer, King was elected president of the student body.[28] The African-American students of Crozer for the most part conducted their social activity on Edwards Street. King became fond of the street because a classmate had an aunt who prepared collard greens for them, which they both relished.[29]

King once reproved another student for keeping beer in his room, saying they had shared responsibility as African Americans to bear "the burdens of the Negro race." For a time, he was interested in Walter Rauschenbusch's "social gospel."[28] In his third year at Crozer, King became romantically involved with the white daughter of an immigrant German woman who worked as a cook in the cafeteria. The daughter had been involved with a professor prior to her relationship with King. King planned to marry her, but friends advised against it, saying that an interracial marriage would provoke animosity from both blacks and whites, potentially damaging his chances of ever pastoring a church in the South. King tearfully told a friend that he could not endure his mother's pain over the marriage and broke the relationship off six months later. He continued to have lingering feelings toward the women he left; one friend was quoted as saying, "He never recovered."[28]

King married Coretta Scott on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents' house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama.[30] They became the parents of four children: Yolanda King (1955–2007), Martin Luther King III (b. 1957), Dexter Scott King (b. 1961), and Bernice King (b. 1963).[31] During their marriage, King limited Coretta's role in the civil rights movement, expecting her to be a housewife and mother.[32]

At the age of 25 in 1954, King was called as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama.[33]

Doctoral studies

King began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University and received his Ph.D. degree on June 5, 1955, with a dissertation (initially supervised by Edgar S. Brightman and, upon the latter's death, by Lotan Harold DeWolf) titled A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman.[34] While pursuing doctoral studies, King worked as an assistant minister at Boston's historic Twelfth Baptist Church with Rev. William Hunter Hester. Hester was an old friend of King's father, and was an important influence on King.[35]

Decades later, an academic inquiry in October 1991 concluded that portions of his dissertation had been plagiarized and he had acted improperly. However, "[d]espite its finding, the committee said that 'no thought should be given to the revocation of Dr. King's doctoral degree,' an action that the panel said would serve no purpose."[34][5][36] The committee also found that the dissertation still "makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship." A letter is now attached to the copy of King's dissertation held in the university library, noting that numerous passages were included without the appropriate quotations and citations of sources.[37] Significant debate exists on how to interpret King's plagiarism.[38]

Montgomery bus boycott, 1955

Rosa Parks with King, 1955

In March 1955, Claudette Colvin—a fifteen-year-old black schoolgirl in Montgomery—refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in violation of Jim Crow laws, local laws in the Southern United States that enforced racial segregation. King was on the committee from the Birmingham African-American community that looked into the case; E. D. Nixon and Clifford Durr decided to wait for a better case to pursue because the incident involved a minor.[39]

Nine months later on December 1, 1955, a similar incident occurred when Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus.[40] The two incidents led to the Montgomery bus boycott, which was urged and planned by Nixon and led by King.[41] The boycott lasted for 385 days,[42] and the situation became so tense that King's house was bombed.[43] King was arrested during this campaign, which concluded with a United States District Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle that ended racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses.[44][45] King's role in the bus boycott transformed him into a national figure and the best-known spokesman of the civil rights movement.[46]

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Joseph Lowery, and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The group was created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the service of civil rights reform. The group was inspired by the crusades of evangelist Billy Graham, who befriended King after he attended a 1957 Graham crusade in New York City.[47] King led the SCLC until his death.[48] The SCLC's 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom was the first time King addressed a national audience.[49] Other civil rights leaders involved in the SCLC with King included: James Bevel, Allen Johnson, Curtis W. Harris, Walter E. Fauntroy, C. T. Vivian, Andrew Young, The Freedom Singers, Charles Evers, Cleveland Robinson, Randolph Blackwell, Annie Bell Robinson Devine, Charles Kenzie Steele, Alfred Daniel Williams King, Benjamin Hooks, Aaron Henry and Bayard Rustin.[50]

On September 20, 1958, King was signing copies of his book Stride Toward Freedom in Blumstein's department store in Harlem[51] when he narrowly escaped death. Izola Curry—a mentally ill black woman who thought that King was conspiring against her with communists—stabbed him in the chest with a letter opener. King underwent emergency surgery with three doctors: Aubre de Lambert Maynard, Emil Naclerio and John W. V. Cordice; he remained hospitalized for several weeks. Curry was later found mentally incompetent to stand trial.[52][53] In 1959, he published a short book called The Measure of A Man, which contained his sermons "What is Man?" and "The Dimensions of a Complete Life." The sermons argued for man's need for God's love and criticized the racial injustices of Western civilization.[54]

Harry Wachtel joined King's legal advisor Clarence B. Jones in defending four ministers of the SCLC in the libel case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan; the case was litigated in reference to the newspaper advertisement "Heed Their Rising Voices". Wachtel founded a tax-exempt fund to cover the expenses of the suit and to assist the nonviolent civil rights movement through a more effective means of fundraising. This organization was named the "Gandhi Society for Human Rights." King served as honorary president for the group. He was displeased with the pace that President Kennedy was using to address the issue of segregation. In 1962, King and the Gandhi Society produced a document that called on the President to follow in the footsteps of Abraham Lincoln and issue an executive order to deliver a blow for civil rights as a kind of Second Emancipation Proclamation. Kennedy did not execute the order.[55]

Lyndon B. Johnson and Robert F. Kennedy with civil rights leaders, June 22, 1963

The FBI was under written directive from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy when it began tapping King's telephone line in the fall of 1963.[56]

Kennedy was concerned that public allegations of communists in the SCLC would derail the administration's civil rights initiatives. He warned King to discontinue these associations and later felt compelled to issue the written directive that authorized the FBI to wiretap King and other SCLC leaders.[57] FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover feared the civil rights movement and investigated the allegations of communist infiltration. When no evidence emerged to support this, the FBI used the incidental details caught on tape over the next five years in attempts to force King out of his leadership position, in the COINTELPRO program.[58]

King believed that organized, nonviolent protest against the system of southern segregation known as Jim Crow laws would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by Southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that convinced the majority of Americans that the civil rights movement was the most important issue in American politics in the early 1960s.[59][60]

King organized and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights.[45] Most of these rights were successfully enacted into the law of the United States with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.[61][62]

King and the SCLC put into practice many of the principles of the Christian Left and applied the tactics of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the method of protest and the places in which protests were carried out. There were often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent.[63]

King was criticized by many groups during the course of his participation in the civil rights movement. This included opposition by more militant blacks such as Nation of Islam member Malcolm X.[64]Stokely Carmichael was a separatist and disagreed with King's plea for racial integration because he considered it an insult to a uniquely African-American culture.[65]Omali Yeshitela urged Africans to remember the history of violent European colonization and how power was not secured by Europeans through integration, but by violence and force.[66]

Albany Movement, 1961

The Albany Movement was a desegregation coalition formed in Albany, Georgia, in November 1961. In December, King and the SCLC became involved. The movement mobilized thousands of citizens for a broad-front nonviolent attack on every aspect of segregation within the city and attracted nationwide attention. When King first visited on December 15, 1961, he "had planned to stay a day or so and return home after giving counsel."[67]

The following day he was swept up in a mass arrest of peaceful demonstrators, and he declined bail until the city made concessions. According to King, "that agreement was dishonored and violated by the city" after he left town.[67]

King returned in July 1962 and was given the option of forty-five days in jail or a $178 fine (equivalent to $1,400 in 2017); he chose jail. Three days into his sentence, Police Chief Laurie Pritchett discreetly arranged for King's fine to be paid and ordered his release. "We had witnessed persons being kicked off lunch counter stools ... ejected from churches ... and thrown into jail ... But for the first time, we witnessed being kicked out of jail."[68] It was later acknowledged by the King Center that Billy Graham was the one who bailed King out of jail during this time.[69]

After nearly a year of intense activism with few tangible results, the movement began to deteriorate. King requested a halt to all demonstrations and a "Day of Penance" to promote nonviolence and maintain the moral high ground. Divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts.[70] Though the Albany effort proved a key lesson in tactics for King and the national civil rights movement,[71] the national media was highly critical of King's role in the defeat, and the SCLC's lack of results contributed to a growing gulf between the organization and the more radical SNCC. After Albany, King sought to choose engagements for the SCLC in which he could control the circumstances, rather than entering into pre-existing situations.[72]

Birmingham campaign, 1963

King was arrested in 1963 for protesting the treatment of blacks in Birmingham.

In April 1963, the SCLC began a campaign against racial segregation and economic injustice in Birmingham, Alabama. The campaign used nonviolent but intentionally confrontational tactics, developed in part by Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker. Black people in Birmingham, organizing with the SCLC, occupied public spaces with marches and sit-ins, openly violating laws that they considered unjust.

King's intent was to provoke mass arrests and "create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation."[73] The campaign's early volunteers did not succeed in shutting down the city, or in drawing media attention to the police's actions. Over the concerns of an uncertain King, SCLC strategist James Bevel changed the course of the campaign by recruiting children and young adults to join in the demonstrations.[74]Newsweek called this strategy a Children's Crusade.[75][76]

During the protests, the Birmingham Police Department, led by Eugene "Bull" Connor, used high-pressure water jets and police dogs against protesters, including children. Footage of the police response was broadcast on national television news and dominated the nation's attention, shocking many white Americans and consolidating black Americans behind the movement.[77] Not all of the demonstrators were peaceful, despite the avowed intentions of the SCLC. In some cases, bystanders attacked the police, who responded with force. King and the SCLC were criticized for putting children in harm's way. But the campaign was a success: Connor lost his job, the "Jim Crow" signs came down, and public places became more open to blacks. King's reputation improved immensely.[75]

King was arrested and jailed early in the campaign—his 13th arrest[78] out of 29.[79] From his cell, he composed the now-famous Letter from Birmingham Jail that responds to calls on the movement to pursue legal channels for social change. King argues that the crisis of racism is too urgent, and the current system too entrenched: "We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed."[80] He points out that the Boston Tea Party, a celebrated act of rebellion in the American colonies, was illegal civil disobedience, and that, conversely, "everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was 'legal'."[80] King also expresses his frustration with white moderates and clergymen too timid to oppose an unjust system:

I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action"; who paternalistic-ally believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a "more convenient season."[80]

St. Augustine, Florida, 1964

In March 1964, King and the SCLC joined forces with Robert Hayling's then-controversial movement in St. Augustine, Florida. Hayling's group had been affiliated with the NAACP but was forced out of the organization for advocating armed self-defense alongside nonviolent tactics. However, the pacifist SCLC accepted them.[81] King and the SCLC worked to bring white Northern activists to St. Augustine, including a delegation of rabbis and the 72-year-old mother of the governor of Massachusetts, all of whom were arrested.[82][83]

During June, the movement marched nightly through the city, "often facing counter demonstrations by the Klan, and provoking violence that garnered national media attention." Hundreds of the marchers were arrested and jailed. During the course of this movement, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed.[84]

Selma, Alabama, 1964

In December 1964, King and the SCLC joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Selma, Alabama, where the SNCC had been working on voter registration for several months.[85]

A local judge issued an injunction that barred any gathering of three or more people affiliated with the SNCC, SCLC, DCVL, or any of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil rights activity until King defied it by speaking at Brown Chapel on January 2, 1965.[86] During the 1965 march to Montgomery, Alabama, violence by state police and others against the peaceful marchers resulted in much publicity, which made Alabama's racism visible nationwide.

New York City, 1964

On February 6, 1964, King delivered the inaugural speech of a lecture series initiated at the New School called "The American Race Crisis." No audio record of his speech has been found, but in August 2013, almost 50 years later, the school discovered an audiotape with 15 minutes of a question-and-answer session that followed King's address. In these remarks, King referred to a conversation he had recently had with Jawaharlal Nehru in which he compared the sad condition of many African Americans to that of India's untouchables.[87]

March on Washington, 1963

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963).

King, representing the SCLC, was among the leaders of the "Big Six" civil rights organizations who were instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which took place on August 28, 1963. The other leaders and organizations comprising the Big Six were Roy Wilkins from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; Whitney Young, National Urban League; A. Philip Randolph, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; John Lewis, SNCC; and James L. Farmer Jr., of the Congress of Racial Equality.[88]

Bayard Rustin's open homosexuality, support of democratic socialism, and his former ties to the Communist Party USA caused many white and African-American leaders to demand King distance himself from Rustin,[89] which King agreed to do.[90] However, he did collaborate in the 1963 March on Washington, for which Rustin was the primary logistical and strategic organizer.[91][92]

For King, this role was another which courted controversy, since he was one of the key figures who acceded to the wishes of United States President John F. Kennedy in changing the focus of the march.[93][94]

Kennedy initially opposed the march outright, because he was concerned it would negatively impact the drive for passage of civil rights legislation. However, the organizers were firm that the march would proceed.[95] With the march going forward, the Kennedys decided it was important to work to ensure its success. President Kennedy was concerned the turnout would be less than 100,000. Therefore, he enlisted the aid of additional church leaders and Walter Reuther, president of the United Automobile Workers, to help mobilize demonstrators for the cause.[96]

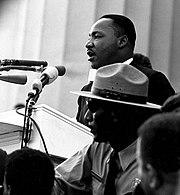

King gave his most famous speech, "I Have a Dream", before the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

The march originally was conceived as an event to dramatize the desperate condition of blacks in the southern U.S. and an opportunity to place organizers' concerns and grievances squarely before the seat of power in the nation's capital. Organizers intended to denounce the federal government for its failure to safeguard the civil rights and physical safety of civil rights workers and blacks. The group acquiesced to presidential pressure and influence, and the event ultimately took on a far less strident tone.[97]

As a result, some civil rights activists felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the "Farce on Washington", and the Nation of Islam forbade its members from attending the march.[97][98]

I Have a Dream 30-second sample from "I Have a Dream" speech by Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963 | |

Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The march made specific demands: an end to racial segregation in public schools; meaningful civil rights legislation, including a law prohibiting racial discrimination in employment; protection of civil rights workers from police brutality; a $2 minimum wage for all workers (equivalent to $16 in 2017); and self-government for Washington, D.C., then governed by congressional committee.[99][100][101]

Despite tensions, the march was a resounding success.[102] More than a quarter of a million people of diverse ethnicities attended the event, sprawling from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial onto the National Mall and around the reflecting pool. At the time, it was the largest gathering of protesters in Washington, D.C.'s history.[102]

King delivered a 17-minute speech, later known as "I Have a Dream". In the speech's most famous passage—in which he departed from his prepared text, possibly at the prompting of Mahalia Jackson, who shouted behind him, "Tell them about the dream!"[103][104]—King said:[105]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.'

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification; one day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today.

"I Have a Dream" came to be regarded as one of the finest speeches in the history of American oratory.[106]

The March, and especially King's speech, helped put civil rights at the top of the agenda of reformers in the United States and facilitated passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[107][108]

The original typewritten copy of the speech, including King's handwritten notes on it, was discovered in 1984 to be in the hands of George Raveling, the first African-American basketball coach of the University of Iowa. In 1963, Raveling, then 26, was standing near the podium, and immediately after the oration, impulsively asked King if he could have his copy of the speech. He got it.[109]

Selma voting rights movement and "Bloody Sunday", 1965

The civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965.

Acting on James Bevel's call for a march from Selma to Montgomery, King, Bevel, and the SCLC, in partial collaboration with SNCC, attempted to organize the march to the state's capital. The first attempt to march on March 7, 1965, was aborted because of mob and police violence against the demonstrators. This day has become known as Bloody Sunday and was a major turning point in the effort to gain public support for the civil rights movement. It was the clearest demonstration up to that time of the dramatic potential of King's nonviolence strategy. King, however, was not present.[18]

On March 5, King met with officials in the Johnson Administration in order to request an injunction against any prosecution of the demonstrators. He did not attend the march due to church duties, but he later wrote, "If I had any idea that the state troopers would use the kind of brutality they did, I would have felt compelled to give up my church duties altogether to lead the line."[110] Footage of police brutality against the protesters was broadcast extensively and aroused national public outrage.[111]

King next attempted to organize a march for March 9. The SCLC petitioned for an injunction in federal court against the State of Alabama; this was denied and the judge issued an order blocking the march until after a hearing. Nonetheless, King led marchers on March 9 to the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, then held a short prayer session before turning the marchers around and asking them to disperse so as not to violate the court order. The unexpected ending of this second march aroused the surprise and anger of many within the local movement.[112] The march finally went ahead fully on March 25, 1965.[113][114]

At the conclusion of the march on the steps of the state capitol, King delivered a speech that became known as "How Long, Not Long." In it, King stated that equal rights for African Americans could not be far away, "because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice" and "you shall reap what you sow".[a][115][116][117]

Chicago open housing movement, 1966

King stands behind President Johnson as he signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

In 1966, after several successes in the south, King, Bevel, and others in the civil rights organizations took the movement to the North, with Chicago as their first destination. King and Ralph Abernathy, both from the middle class, moved into a building at 1550 S. Hamlin Avenue, in the slums of North Lawndale[118]

on Chicago's West Side, as an educational experience and to demonstrate their support and empathy for the poor.[119]

The SCLC formed a coalition with CCCO, Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, an organization founded by Albert Raby, and the combined organizations' efforts were fostered under the aegis of the Chicago Freedom Movement.[120]

During that spring, several white couple/black couple tests of real estate offices uncovered racial steering: discriminatory processing of housing requests by couples who were exact matches in income, background, number of children, and other attributes.[121] Several larger marches were planned and executed: in Bogan, Belmont Cragin, Jefferson Park, Evergreen Park (a suburb southwest of Chicago), Gage Park, Marquette Park, and others.[120][122][123]

President Lyndon B. Johnson meeting with King in the White House Cabinet Room, 1966

King later stated and Abernathy wrote that the movement received a worse reception in Chicago than in the South. Marches, especially the one through Marquette Park on August 5, 1966, were met by thrown bottles and screaming throngs. Rioting seemed very possible.[124][125]

King's beliefs militated against his staging a violent event, and he negotiated an agreement with Mayor Richard J. Daley to cancel a march in order to avoid the violence that he feared would result.[126]

King was hit by a brick during one march but continued to lead marches in the face of personal danger.[127]

When King and his allies returned to the South, they left Jesse Jackson, a seminary student who had previously joined the movement in the South, in charge of their organization.[128]

Jackson continued their struggle for civil rights by organizing the Operation Breadbasket movement that targeted chain stores that did not deal fairly with blacks.[129]

A 1967 CIA document declassified in 2017 downplayed King's role in the "black militant situation" in Chicago, with a source stating that King "sought at least constructive, positive projects."[130]

Opposition to the Vietnam War

King was long opposed to American involvement in the Vietnam War,[131] but at first avoided the topic in public speeches in order to avoid the interference with civil rights goals that criticism of President Johnson's policies might have created.[131] At the urging of SCLC's former Director of Direct Action and now the head of the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, James Bevel,[132] King eventually agreed to publicly oppose the war as opposition was growing among the American public.[131]

During an April 4, 1967, appearance at the New York City Riverside Church—exactly one year before his death—King delivered a speech titled "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence."[133]

He spoke strongly against the U.S.'s role in the war, arguing that the U.S. was in Vietnam "to occupy it as an American colony"[134] and calling the U.S. government "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today."[135] He also connected the war with economic injustice, arguing that the country needed serious moral change:

A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. With righteous indignation, it will look across the seas and see individual capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia, Africa and South America, only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries, and say: "This is not just."[136]

King also opposed the Vietnam War because it took money and resources that could have been spent on social welfare at home. The United States Congress was spending more and more on the military and less and less on anti-poverty programs at the same time. He summed up this aspect by saying, "A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death."[136] He stated that North Vietnam "did not begin to send in any large number of supplies or men until American forces had arrived in the tens of thousands",[137] and accused the U.S. of having killed a million Vietnamese, "mostly children."[138]

King also criticized American opposition to North Vietnam's land reforms.[139]

King's opposition cost him significant support among white allies, including President Johnson, Billy Graham,[140] union leaders and powerful publishers.[141]

"The press is being stacked against me", King said,[142]

complaining of what he described as a double standard that applauded his nonviolence at home, but deplored it when applied "toward little brown Vietnamese children."[143]Life magazine called the speech "demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi",[136] and The Washington Post declared that King had "diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people."[143][144]

King speaking to an anti-Vietnam war rally at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul, April 27, 1967

The "Beyond Vietnam" speech reflected King's evolving political advocacy in his later years, which paralleled the teachings of the progressive Highlander Research and Education Center, with which he was affiliated.[145][146]

King began to speak of the need for fundamental changes in the political and economic life of the nation, and more frequently expressed his opposition to the war and his desire to see a redistribution of resources to correct racial and economic injustice.[147]

He guarded his language in public to avoid being linked to communism by his enemies, but in private he sometimes spoke of his support for democratic socialism.[148][149]

In a 1952 letter to Coretta Scott, he said: "I imagine you already know that I am much more socialistic in my economic theory than capitalistic ..."[150] In one speech, he stated that "something is wrong with capitalism" and claimed, "There must be a better distribution of wealth, and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism."[151]

King had read Marx while at Morehouse, but while he rejected "traditional capitalism", he also rejected communism because of its "materialistic interpretation of history" that denied religion, its "ethical relativism", and its "political totalitarianism."[152]

King also stated in "Beyond Vietnam" that "true compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar ... it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring."[153] King quoted a United States official who said that from Vietnam to Latin America, the country was "on the wrong side of a world revolution."[153] King condemned America's "alliance with the landed gentry of Latin America", and said that the U.S. should support "the shirtless and barefoot people" in the Third World rather than suppressing their attempts at revolution.[153]

King's stance on Vietnam encouraged Allard K. Lowenstein, William Sloane Coffin and Norman Thomas, with the support of anti-war Democrats, to attempt to persuade King to run against President Johnson in the 1968 United States presidential election. King contemplated but ultimately decided against the proposal on the grounds that he felt uneasy with politics and considered himself better suited for his morally unambiguous role as an activist.[154]

On April 15, 1967, King participated and spoke at an anti-war march from Manhattan's Central Park to the United Nations. The march was organized by the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam and initiated by its chairman, James Bevel. At the U.N. King also brought up issues of civil rights and the draft.

I have not urged a mechanical fusion of the civil rights and peace movements. There are people who have come to see the moral imperative of equality, but who cannot yet see the moral imperative of world brotherhood. I would like to see the fervor of the civil-rights movement imbued into the peace movement to instill it with greater strength. And I believe everyone has a duty to be in both the civil-rights and peace movements. But for those who presently choose but one, I would hope they will finally come to see the moral roots common to both.[155]

Seeing an opportunity to unite civil rights activists and anti-war activists,[132] Bevel convinced King to become even more active in the anti-war effort.[132] Despite his growing public opposition towards the Vietnam War, King was also not fond of the hippie culture which developed from the anti-war movement.[156] In his 1967 Massey Lecture, King stated:

The importance of the hippies is not in their unconventional behavior, but in the fact that hundreds of thousands of young people, in turning to a flight from reality, are expressing a profoundly discrediting view on the society they emerge from.[156]

On January 13, 1968 (the day after President Johnson's State of the Union Address), King called for a large march on Washington against "one of history's most cruel and senseless wars."[157][158]

We need to make clear in this political year, to congressmen on both sides of the aisle and to the president of the United States, that we will no longer tolerate, we will no longer vote for men who continue to see the killings of Vietnamese and Americans as the best way of advancing the goals of freedom and self-determination in Southeast Asia.[157][158]

Poor People's Campaign, 1968

A shantytown established in Washington, D. C. to protest economic conditions as a part of the Poor People's Campaign.

In 1968, King and the SCLC organized the "Poor People's Campaign" to address issues of economic justice. King traveled the country to assemble "a multiracial army of the poor" that would march on Washington to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience at the Capitol until Congress created an "economic bill of rights" for poor Americans.[159][160]

The campaign was preceded by King's final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? which laid out his view of how to address social issues and poverty. King quoted from Henry George and George's book, Progress and Poverty, particularly in support of a guaranteed basic income.[161][162][163] The campaign culminated in a march on Washington, D.C., demanding economic aid to the poorest communities of the United States.

King and the SCLC called on the government to invest in rebuilding America's cities. He felt that Congress had shown "hostility to the poor" by spending "military funds with alacrity and generosity." He contrasted this with the situation faced by poor Americans, claiming that Congress had merely provided "poverty funds with miserliness."[160] His vision was for change that was more revolutionary than mere reform: he cited systematic flaws of "racism, poverty, militarism and materialism", and argued that "reconstruction of society itself is the real issue to be faced."[164]

The Poor People's Campaign was controversial even within the civil rights movement. Rustin resigned from the march, stating that the goals of the campaign were too broad, that its demands were unrealizable, and that he thought that these campaigns would accelerate the backlash and repression on the poor and the black.[165]

After King's death

The plan to set up a shantytown in Washington, D.C., was carried out soon after the April 4 assassination. Criticism of King's plan was subdued in the wake of his death, and the SCLC received an unprecedented wave of donations for the purpose of carrying it out. The campaign officially began in Memphis, on May 2, at the hotel where King was murdered.[166]

Thousands of demonstrators arrived on the National Mall and established a camp they called "Resurrection City." They stayed for six weeks.[167]

Assassination and aftermath

The Lorraine Motel, where King was assassinated, is now the site of the National Civil Rights Museum.

I've Been to the Mountaintop Final 30 seconds of "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech by Martin Luther King Jr. | |

Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

On March 29, 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee, in support of the black sanitary public works employees, who were represented by AFSCME Local 1733. The workers had been on strike since March 12 for higher wages and better treatment. In one incident, black street repairmen received pay for two hours when they were sent home because of bad weather, but white employees were paid for the full day.[168][169][170]

On April 3, King addressed a rally and delivered his "I've Been to the Mountaintop" address at Mason Temple, the world headquarters of the Church of God in Christ. King's flight to Memphis had been delayed by a bomb threat against his plane.[171]

In the prophetic peroration of the last speech of his life, in reference to the bomb threat, King said the following:

And then I got to Memphis. And some began to say the threats, or talk about the threats that were out. What would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers?

Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. So I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.[172]

King was booked in Room 306 at the Lorraine Motel (owned by Walter Bailey) in Memphis. Abernathy, who was present at the assassination, testified to the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations that King and his entourage stayed at Room 306 so often that it was known as the "King-Abernathy suite."[173]

According to Jesse Jackson, who was present, King's last words on the balcony before his assassination were spoken to musician Ben Branch, who was scheduled to perform that night at an event King was attending: "Ben, make sure you play 'Take My Hand, Precious Lord' in the meeting tonight. Play it real pretty."[174]

King was fatally shot by James Earl Ray at 6:01 p.m., April 4, 1968, as he stood on the motel's second-floor balcony. The bullet entered through his right cheek, smashing his jaw, then traveled down his spinal cord before lodging in his shoulder.[175][176]

Abernathy heard the shot from inside the motel room and ran to the balcony to find King on the floor.[177]

Jackson stated after the shooting that he cradled King's head as King lay on the balcony, but this account was disputed by other colleagues of King; Jackson later changed his statement to say that he had "reached out" for King.[178]

After emergency chest surgery, King died at St. Joseph's Hospital at 7:05 p.m.[179]

According to biographer Taylor Branch, King's autopsy revealed that though only 39 years old, he "had the heart of a 60 year old", which Branch attributed to the stress of 13 years in the civil rights movement.[180]

Aftermath

King's friend Mahalia Jackson (seen here in 1964) sang at his funeral.

The assassination led to a nationwide wave of race riots in Washington, D.C., Chicago, Baltimore, Louisville, Kansas City, and dozens of other cities.[181][182] Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy was on his way to Indianapolis for a campaign rally when he was informed of King's death. He gave a short, improvised speech to the gathering of supporters informing them of the tragedy and urging them to continue King's ideal of nonviolence.[183] The following day, he delivered a prepared response in Cleveland.[184]James Farmer Jr., and other civil rights leaders also called for non-violent action, while the more militant Stokely Carmichael called for a more forceful response.[185] The city of Memphis quickly settled the strike on terms favorable to the sanitation workers.[186]

President Lyndon B. Johnson declared April 7 a national day of mourning for the civil rights leader.[187]

Vice President Hubert Humphrey attended King's funeral on behalf of the President, as there were fears that Johnson's presence might incite protests and perhaps violence.[188]

At his widow's request, King's last sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church was played at the funeral,[189]

a recording of his "Drum Major" sermon, given on February 4, 1968. In that sermon, King made a request that at his funeral no mention of his awards and honors be made, but that it be said that he tried to "feed the hungry", "clothe the naked", "be right on the [Vietnam] war question", and "love and serve humanity."[190]

His good friend Mahalia Jackson sang his favorite hymn, "Take My Hand, Precious Lord", at the funeral.[191]

Two months after King's death, James Earl Ray—who was on the loose from a previous prison escape—was captured at London Heathrow Airport while trying to leave England on a false Canadian passport. He was using the alias Ramon George Sneyd on his way to white-ruled Rhodesia.[192]

Ray was quickly extradited to Tennessee and charged with King's murder. He confessed to the assassination on March 10, 1969, though he recanted this confession three days later.[193]

On the advice of his attorney Percy Foreman, Ray pleaded guilty to avoid a trial conviction and thus the possibility of receiving the death penalty. He was sentenced to a 99-year prison term.[193][194]

Ray later claimed a man he met in Montreal, Quebec, with the alias "Raoul" was involved and that the assassination was the result of a conspiracy.[195][196]

He spent the remainder of his life attempting, unsuccessfully, to withdraw his guilty plea and secure the trial he never had.[194] Ray died in 1998 at age 70.[197]

Allegations of conspiracy

The sarcophagus of Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site in Atlanta, Georgia.

Ray's lawyers maintained he was a scapegoat similar to the way that John F. Kennedy's assassin Lee Harvey Oswald is seen by conspiracy theorists.[198]

Supporters of this assertion said that Ray's confession was given under pressure and that he had been threatened with the death penalty.[194][199]

They admitted that Ray was a thief and burglar, but claimed that he had no record of committing violent crimes with a weapon.[196] However, prison records in different U.S. cities have shown that he was incarcerated on numerous occasions for charges of armed robbery.[200] In a 2008 interview with CNN, Jerry Ray, the younger brother of James Earl Ray, claimed that James was smart and was sometimes able to get away with armed robbery. Jerry Ray said that he had assisted his brother on one such robbery. "I never been with nobody as bold as he is," Jerry said. "He just walked in and put that gun on somebody, it was just like it's an everyday thing."[200]

Those suspecting a conspiracy in the assassination point to the two successive ballistics tests which proved that a rifle similar to Ray's Remington Gamemaster had been the murder weapon. Those tests did not implicate Ray's specific rifle.[194][201]

Witnesses near King at the moment of his death said that the shot came from another location. They said that it came from behind thick shrubbery near the boarding house—which had been cut away in the days following the assassination—and not from the boarding house window.[202] However, Ray's fingerprints were found on various objects (a rifle, a pair of binoculars, articles of clothing, a newspaper) that were left in the bathroom where it was determined the gunfire came from.[200] An examination of the rifle containing Ray's fingerprints also determined that at least one shot was fired from the firearm at the time of the assassination.[200]

In 1997, King's son Dexter Scott King met with Ray, and publicly supported Ray's efforts to obtain a new trial.[203]

Two years later, King's widow Coretta Scott King and the couple's children won a wrongful death claim against Loyd Jowers and "other unknown co-conspirators." Jowers claimed to have received $100,000 to arrange King's assassination. The jury of six whites and six blacks found in favor of the King family, finding Jowers to be complicit in a conspiracy against King and that government agencies were party to the assassination.[204][205]William F. Pepper represented the King family in the trial.[206]

In 2000, the U.S. Department of Justice completed the investigation into Jowers' claims but did not find evidence to support allegations about conspiracy. The investigation report recommended no further investigation unless some new reliable facts are presented.[207] A sister of Jowers admitted that he had fabricated the story so he could make $300,000 from selling the story, and she in turn corroborated his story in order to get some money to pay her income tax.[208][209]

In 2002, The New York Times reported that a church minister, Rev. Ronald Denton Wilson, claimed his father, Henry Clay Wilson—not James Earl Ray—assassinated King. He stated, "It wasn't a racist thing; he thought Martin Luther King was connected with communism, and he wanted to get him out of the way." Wilson provided no evidence to back up his claims.[210]

King researchers David Garrow and Gerald Posner disagreed with William F. Pepper's claims that the government killed King.[211]

In 2003, Pepper published a book about the long investigation and trial, as well as his representation of James Earl Ray in his bid for a trial, laying out the evidence and criticizing other accounts.[212][213]

King's friend and colleague, James Bevel, also disputed the argument that Ray acted alone, stating, "There is no way a ten-cent white boy could develop a plan to kill a million-dollar black man."[214]

In 2004, Jesse Jackson stated:

The fact is there were saboteurs to disrupt the march. And within our own organization, we found a very key person who was on the government payroll. So infiltration within, saboteurs from without and the press attacks. ... I will never believe that James Earl Ray had the motive, the money and the mobility to have done it himself. Our government was very involved in setting the stage for and I think the escape route for James Earl Ray.[215]

Legacy

Martin Luther King Jr. statue over the west entrance of Westminster Abbey, installed in 1998.

King's main legacy was to secure progress on civil rights in the U.S. Just days after King's assassination, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968.[216]

Title VIII of the Act, commonly known as the Fair Housing Act, prohibited discrimination in housing and housing-related transactions on the basis of race, religion, or national origin (later expanded to include sex, familial status, and disability). This legislation was seen as a tribute to King's struggle in his final years to combat residential discrimination in the U.S.[216]

Internationally, King's legacy includes influences on the Black Consciousness Movement and civil rights movement in South Africa.[217][218]

King's work was cited by and served as an inspiration for South African leader Albert Lutuli, who fought for racial justice in his country and was later awarded the Nobel Prize.[219] The day following King's assassination, school teacher Jane Elliott conducted her first "Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes" exercise with her class of elementary school students in Riceville, Iowa. Her purpose was to help them understand King's death as it related to racism, something they little understood as they lived in a predominantly white community.[220]

King has become a national icon in the history of American liberalism and American progressivism.[221] King also influenced Irish politician and activist John Hume. Hume, the former leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, cited King's legacy as quintessential to the Northern Irish civil rights movement and the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, calling him "one of my great heroes of the century."[222][223][224]

King's wife Coretta Scott King followed in her husband's footsteps and was active in matters of social justice and civil rights until her death in 2006. The same year that Martin Luther King was assassinated, she established the King Center in Atlanta, Georgia, dedicated to preserving his legacy and the work of championing nonviolent conflict resolution and tolerance worldwide.[225]

Their son, Dexter King, serves as the center's chairman.[226][227]

Daughter Yolanda King, who died in 2007, was a motivational speaker, author and founder of Higher Ground Productions, an organization specializing in diversity training.[228]

Even within the King family, members disagree about his religious and political views about gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people. King's widow Coretta publicly said that she believed her husband would have supported gay rights.[229] However, his youngest child, Bernice King, has said publicly that he would have been opposed to gay marriage.[230]

On February 4, 1968, at the Ebenezer Baptist Church, in speaking about how he wished to be remembered after his death, King stated:

I'd like somebody to mention that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to give his life serving others. I'd like for somebody to say that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to love somebody.

I want you to say that day that I tried to be right on the war question. I want you to be able to say that day that I did try to feed the hungry. I want you to be able to say that day that I did try in my life to clothe those who were naked. I want you to say on that day that I did try in my life to visit those who were in prison. And I want you to say that I tried to love and serve humanity.

Yes, if you want to say that I was a drum major. Say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter. I won't have any money to leave behind. I won't have the fine and luxurious things of life to leave behind. But I just want to leave a committed life behind.[185][231]

Martin Luther King Jr. Day

Beginning in 1971, cities such as St. Louis, Missouri, and states established annual holidays to honor King.[232] At the White House Rose Garden on November 2, 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a federal holiday to honor King. Observed for the first time on January 20, 1986, it is called Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Following President George H. W. Bush's 1992 proclamation, the holiday is observed on the third Monday of January each year, near the time of King's birthday.[233][234]

On January 17, 2000, for the first time, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was officially observed in all fifty U.S. states.[235]Arizona (1992), New Hampshire (1999) and Utah (2000) were the last three states to recognize the holiday. Utah previously celebrated the holiday at the same time but under the name Human Rights Day.[236]

Liturgical commemorations

King is remembered as a martyr by the Episcopal Church in the United States of America with an annual feast day on the anniversary of his death, April 4.[237] The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America commemorates King liturgically on the anniversary of his birth, January 15.[238]

UK legacy and The Martin Luther King Peace Committee

Banner at the 2012 Republican National Convention

In the United Kingdom, The Northumbria and Newcastle Universities Martin Luther King Peace Committee[239] exists to honor King's legacy, as represented by his final visit to the UK to receive an honorary degree from Newcastle University in 1967.[240] The Peace Committee operates out of the chaplaincies of the city's two universities, Northumbria and Newcastle, both of which remain centres for the study of Martin Luther King and the US civil rights movement. Inspired by King's vision, it undertakes a range of activities across the UK as it seeks to "build cultures of peace."

In 2017, Newcastle University unveiled a bronze statue of King to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his honorary doctorate ceremony.[241] The Students Union also voted to rename their bar 'Luthers'.[242]

Ideas, influences, and political stances

Religion

King at the 1963 Civil Rights March in Washington, D.C.

As a Christian minister, King's main influence was Jesus Christ and the Christian gospels, which he would almost always quote in his religious meetings, speeches at church, and in public discourses. King's faith was strongly based in Jesus' commandment of loving your neighbor as yourself, loving God above all, and loving your enemies, praying for them and blessing them. His nonviolent thought was also based in the injunction to turn the other cheek in the Sermon on the Mount, and Jesus' teaching of putting the sword back into its place (Matthew 26:52).[243] In his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail, King urged action consistent with what he describes as Jesus' "extremist" love, and also quoted numerous other Christian pacifist authors, which was very usual for him. In another sermon, he stated:

Before I was a civil rights leader, I was a preacher of the Gospel. This was my first calling and it still remains my greatest commitment. You know, actually all that I do in civil rights I do because I consider it a part of my ministry. I have no other ambitions in life but to achieve excellence in the Christian ministry. I don't plan to run for any political office. I don't plan to do anything but remain a preacher. And what I'm doing in this struggle, along with many others, grows out of my feeling that the preacher must be concerned about the whole man.[244][245]

In his speech "I've Been to the Mountaintop", he stated that he just wanted to do God's will.

Nonviolence

King worked alongside Quakers such as Bayard Rustin to develop non-violent tactics.

Veteran African-American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin was King's first regular advisor on nonviolence.[246] King was also advised by the white activists Harris Wofford and Glenn Smiley.[247] Rustin and Smiley came from the Christian pacifist tradition, and Wofford and Rustin both studied Gandhi's teachings. Rustin had applied nonviolence with the Journey of Reconciliation campaign in the 1940s,[248] and Wofford had been promoting Gandhism to Southern blacks since the early 1950s.[247]

King had initially known little about Gandhi and rarely used the term "nonviolence" during his early years of activism in the early 1950s. King initially believed in and practiced self-defense, even obtaining guns in his household as a means of defense against possible attackers. The pacifists guided King by showing him the alternative of nonviolent resistance, arguing that this would be a better means to accomplish his goals of civil rights than self-defense. King then vowed to no longer personally use arms.[249][250]

In the aftermath of the boycott, King wrote Stride Toward Freedom, which included the chapter Pilgrimage to Nonviolence. King outlined his understanding of nonviolence, which seeks to win an opponent to friendship, rather than to humiliate or defeat him. The chapter draws from an address by Wofford, with Rustin and Stanley Levison also providing guidance and ghostwriting.[251]

King was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi and his success with nonviolent activism, and as a theology student, King described Gandhi as being one of the "individuals who greatly reveal the working of the Spirit of God".[252] King had "for a long time ... wanted to take a trip to India."[253] With assistance from Harris Wofford, the American Friends Service Committee, and other supporters, he was able to fund the journey in April 1959.[254][255] The trip to India affected King, deepening his understanding of nonviolent resistance and his commitment to America's struggle for civil rights. In a radio address made during his final evening in India, King reflected, "Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity."

King's admiration of Gandhi's nonviolence did not diminish in later years. He went so far as to hold up his example when receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, hailing the "successful precedent" of using nonviolence "in a magnificent way by Mohandas K. Gandhi to challenge the might of the British Empire ... He struggled only with the weapons of truth, soul force, non-injury and courage."[256]

Another influence for King's nonviolent method was Henry David Thoreau's essay On Civil Disobedience and its theme of refusing to cooperate with an evil system.[257] He also was greatly influenced by the works of Protestant theologians Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich,[258] and said that Walter Rauschenbusch's Christianity and the Social Crisis left an "indelible imprint" on his thinking by giving him a theological grounding for his social concerns.[259][260] King was moved by Rauschenbusch's vision of Christians spreading social unrest in "perpetual but friendly conflict" with the state, simultaneously critiquing it and calling it to act as an instrument of justice.[261] He was apparently unaware of the American tradition of Christian pacifism exemplified by Adin Ballou and William Lloyd Garrison[262] King frequently referred to Jesus' Sermon on the Mount as central for his work.[263][264][265][260] King also sometimes used the concept of "agape" (brotherly Christian love).[266] However, after 1960, he ceased employing it in his writings.[267]

Even after renouncing his personal use of guns, King had a complex relationship with the phenomenon of self-defense in the movement. He publicly discouraged it as a widespread practice, but acknowledged that it was sometimes necessary.[268] Throughout his career King was frequently protected by other civil rights activists who carried arms, such as Colonel Stone Johnson,[269]Robert Hayling, and the Deacons for Defense and Justice.[270][271]

Politics

As the leader of the SCLC, King maintained a policy of not publicly endorsing a U.S. political party or candidate: "I feel someone must remain in the position of non-alignment, so that he can look objectively at both parties and be the conscience of both—not the servant or master of either."[272]

In a 1958 interview, he expressed his view that neither party was perfect, saying, "I don't think the Republican party is a party full of the almighty God nor is the Democratic party. They both have weaknesses ... And I'm not inextricably bound to either party."[273]

King did praise Democratic Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois as being the "greatest of all senators" because of his fierce advocacy for civil rights causes over the years.[274]

King critiqued both parties' performance on promoting racial equality:

Actually, the Negro has been betrayed by both the Republican and the Democratic party. The Democrats have betrayed him by capitulating to the whims and caprices of the Southern Dixiecrats. The Republicans have betrayed him by capitulating to the blatant hypocrisy of reactionary right wing northern Republicans. And this coalition of southern Dixiecrats and right wing reactionary northern Republicans defeats every bill and every move towards liberal legislation in the area of civil rights.[275]

Although King never publicly supported a political party or candidate for president, in a letter to a civil rights supporter in October 1956 he said that he was undecided as to whether he would vote for Adlai Stevenson or Dwight Eisenhower, but that "In the past I always voted the Democratic ticket."[276]

In his autobiography, King says that in 1960 he privately voted for Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy: "I felt that Kennedy would make the best president. I never came out with an endorsement. My father did, but I never made one." King adds that he likely would have made an exception to his non-endorsement policy for a second Kennedy term, saying "Had President Kennedy lived, I would probably have endorsed him in 1964."[277]

In 1964, King urged his supporters "and all people of goodwill" to vote against Republican Senator Barry Goldwater for president, saying that his election "would be a tragedy, and certainly suicidal almost, for the nation and the world."[278]

King supported the ideals of democratic socialism, although he was reluctant to speak directly of this support due to the anti-communist sentiment being projected throughout the United States at the time, and the association of socialism with communism. King believed that capitalism could not adequately provide the basic necessities of many American people, particularly the African-American community.[279]

Compensation

King stated that black Americans, as well as other disadvantaged Americans, should be compensated for historical wrongs. In an interview conducted for Playboy in 1965, he said that granting black Americans only equality could not realistically close the economic gap between them and whites. King said that he did not seek a full restitution of wages lost to slavery, which he believed impossible, but proposed a government compensatory program of $50 billion over ten years to all disadvantaged groups.[280]

He posited that "the money spent would be more than amply justified by the benefits that would accrue to the nation through a spectacular decline in school dropouts, family breakups, crime rates, illegitimacy, swollen relief rolls, rioting and other social evils."[281] He presented this idea as an application of the common law regarding settlement of unpaid labor, but clarified that he felt that the money should not be spent exclusively on blacks. He stated, "It should benefit the disadvantaged of all races."[282]

Family planning

On being awarded the Planned Parenthood Federation of America's Margaret Sanger Award on May 5, 1966, King said:

Recently, the press has been filled with reports of sightings of flying saucers. While we need not give credence to these stories, they allow our imagination to speculate on how visitors from outer space would judge us. I am afraid they would be stupefied at our conduct. They would observe that for death planning we spend billions to create engines and strategies for war. They would also observe that we spend millions to prevent death by disease and other causes. Finally they would observe that we spend paltry sums for population planning, even though its spontaneous growth is an urgent threat to life on our planet. Our visitors from outer space could be forgiven if they reported home that our planet is inhabited by a race of insane men whose future is bleak and uncertain.

There is no human circumstance more tragic than the persisting existence of a harmful condition for which a remedy is readily available. Family planning, to relate population to world resources, is possible, practical and necessary. Unlike plagues of the dark ages or contemporary diseases we do not yet understand, the modern plague of overpopulation is soluble by means we have discovered and with resources we possess.

What is lacking is not sufficient knowledge of the solution but universal consciousness of the gravity of the problem and education of the billions who are its victims...[283][284]

FBI and King's personal life

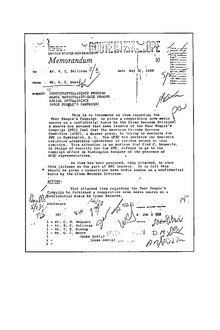

Memo describing FBI attempts to disrupt the Poor People's Campaign with fraudulent claims about King—part of the COINTELPRO campaign against the anti-war and civil rights movements

FBI surveillance and wiretapping

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover personally ordered surveillance of King, with the intent to undermine his power as a civil rights leader.[141][285]

According to the Church Committee, a 1975 investigation by the U.S. Congress, "From December 1963 until his death in 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was the target of an intensive campaign by the Federal Bureau of Investigation to 'neutralize' him as an effective civil rights leader."[286]

In the fall of 1963, the FBI received authorization from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to proceed with wiretapping of King's phone lines.[287] The Bureau informed President John F. Kennedy. He and his brother unsuccessfully tried to persuade King to dissociate himself from Stanley Levison, a New York lawyer who had been involved with Communist Party USA.[288][289] Although Robert Kennedy only gave written approval for limited wiretapping of King's telephone lines "on a trial basis, for a month or so",[290] Hoover extended the clearance so his men were "unshackled" to look for evidence in any areas of King's life they deemed worthy.[57]

The Bureau placed wiretaps on the home and office phone lines of Levison and King, and bugged King's rooms in hotels as he traveled across the country.[288][291]

In 1967, Hoover listed the SCLC as a black nationalist hate group, with the instructions: "No opportunity should be missed to exploit through counterintelligence techniques the organizational and personal conflicts of the leaderships of the groups ... to insure the targeted group is disrupted, ridiculed, or discredited."[285][292]

NSA monitoring of King's communications

In a secret operation code-named "Minaret", the National Security Agency (NSA) monitored the communications of leading Americans, including King, who criticized the U.S. war in Vietnam.[293] A review by the NSA itself concluded that Minaret was "disreputable if not outright illegal."[293]

Allegations of communism

For years, Hoover had been suspicious about potential influence of communists in social movements such as labor unions and civil rights.[294]

Hoover directed the FBI to track King in 1957, and the SCLC as it was established (it did not have a full-time executive director until 1960).[58] The investigations were largely superficial until 1962, when the FBI learned that one of King's most trusted advisers was New York City lawyer Stanley Levison.[295]