Freedom of religion

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Freedom of religion | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Concepts

| ||||||||||||

Status by country

| ||||||||||||

Religious persecution

| ||||||||||||

Religion portal | ||||||||||||

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance without government influence or intervention. It also includes the freedom to change one's religion or belief.[1]

Freedom of religion is considered by many people and most of the nations to be a fundamental human right.[2][3] In a country with a state religion, freedom of religion is generally considered to mean that the government permits religious practices of other sects besides the state religion, and does not persecute believers in other faiths.

Freedom of belief is different. It allows the right to believe what a person, group or religion wishes, but it does not necessarily allow the right to practice the religion or belief openly and outwardly in a public manner.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Muslim world

1.2 India

1.3 Europe

1.3.1 Religious intolerance

1.3.2 Early steps and attempts in the way of tolerance

1.4 Early laws and legal guarantees for religious freedom

1.4.1 Principality of Transylvania

1.4.1.1 Habsburg rule in Transylvania

1.4.2 Netherlands

1.4.3 Poland

1.4.4 Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

1.5 United States

1.6 Canada

1.7 International

2 Contemporary debates

2.1 Theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs

2.2 Liberal secular

2.3 Hinduism

2.4 Judaism

2.5 Christianity

2.6 Islam

2.7 Changing religion

2.7.1 Apostasy in Islam

2.8 Secular law

3 Children's rights

4 International Religious Freedom Day

5 Modern concerns

5.1 Social hostilities and government restrictions

6 See also

7 References

8 Further reading

9 External links

History

Minerva as a symbol of enlightened wisdom protects the believers of all religions (Daniel Chodowiecki, 1791)

Historically, freedom of religion has been used to refer to the tolerance of different theological systems of belief, while freedom of worship has been defined as freedom of individual action. Nevertheless, freedom from religion is a far more pressing moralistic, legal, and peaceful solution. Each of these have existed to varying degrees. While many countries have accepted some form of religious freedom, this has also often been limited in practice through punitive taxation, repressive social legislation, and political disenfranchisement. Compare examples of individual freedom in Italy or the Muslim tradition of dhimmis, literally "protected individuals" professing an officially tolerated non-Muslim religion.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789) guarantees freedom of religion, as long as religious activities do not infringe on public order in ways detrimental to society.

In Antiquity, a syncretic point of view often allowed communities of traders to operate under their own customs. When street mobs of separate quarters clashed in a Hellenistic or Roman city, the issue was generally perceived to be an infringement of community rights.

Cyrus the Great established the Achaemenid Empire ca. 550 BC, and initiated a general policy of permitting religious freedom throughout the empire, documenting this on the Cyrus Cylinder.[4][5]

Some of the historical exceptions have been in regions where one of the revealed religions has been in a position of power: Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity and Islam. Others have been where the established order has felt threatened, as shown in the trial of Socrates in 399 BC or where the ruler has been deified, as in Rome, and refusal to offer token sacrifice was similar to refusing to take an oath of allegiance. This was the core for resentment and the persecution of early Christian communities.

Freedom of religious worship was established in the Buddhist Maurya Empire of ancient India by Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century BC, which was encapsulated in the Edicts of Ashoka.

Greek-Jewish clashes at Cyrene in 73 AD and 117 AD and in Alexandria in 115 AD provide examples of cosmopolitan cities as scenes of tumult.

Muslim world

Following a period of fighting lasting around a hundred years before 620 AD which mainly involved Arab and Jewish inhabitants of Medina (then known as Yathrib), religious freedom for Muslims, Jews and pagans was declared by Muhammad in the Constitution of Medina. The Islamic Caliphate later guaranteed religious freedom under the conditions that non-Muslim communities accept dhimmi status and their adult males pay the punitive jizya tax instead of the zakat paid by Muslim citizens.[6] Though Dhimmis were not given the same political rights as Muslims, they nevertheless did enjoy equality under the laws of property, contract, and obligation.[7][8][9]

Religious pluralism existed in classical Islamic ethics and Sharia, as the religious laws and courts of other religions, including Christianity, Judaism and Hinduism, were usually accommodated within the Islamic legal framework, as seen in the early Caliphate, Al-Andalus, Indian subcontinent, and the Ottoman Millet system.[10][11] In medieval Islamic societies, the qadi (Islamic judges) usually could not interfere in the matters of non-Muslims unless the parties voluntarily choose to be judged according to Islamic law, thus the dhimmi communities living in Islamic states usually had their own laws independent from the Sharia law, such as the Jews who would have their own Halakha courts.[12]

Dhimmis were allowed to operate their own courts following their own legal systems in cases that did not involve other religious groups, or capital offences or threats to public order.[13] Non-Muslims were allowed to engage in religious practices that were usually forbidden by Islamic law, such as the consumption of alcohol and pork, as well as religious practices which Muslims found repugnant, such as the Zoroastrian practice of incestuous "self-marriage" where a man could marry his mother, sister or daughter. According to the famous Islamic legal scholar Ibn Qayyim (1292–1350), non-Muslims had the right to engage in such religious practices even if it offended Muslims, under the conditions that such cases not be presented to Islamic Sharia courts and that these religious minorities believed that the practice in question is permissible according to their religion.[14]

Despite Dhimmis enjoying special statuses under the Caliphates, they were not considered equals, and sporadic persecutions of non-Muslim groups did occur in the history of the Caliphates.[15][16][17]

India

Ancient Jews fleeing from persecution in their homeland 2,500 years ago settled in India and never faced anti-Semitism.[18] Freedom of religion edicts have been found written during Ashoka the Great's reign in the 3rd century BC. Freedom to practise, preach and propagate any religion is a constitutional right in Modern India. Most major religious festivals of the main communities are included in the list of national holidays.

Although India is an 80% Hindu country, India is a secular state without any state religions.

Many scholars and intellectuals believe that India's predominant religion, Hinduism, has long been a most tolerant religion.[19]Rajni Kothari, founder of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies has written, "[India] is a country built on the foundations of a civilisation that is fundamentally non-religious."[20]

The Dalai Lama, the Tibetan leader in exile, said that religious tolerance of 'Aryabhoomi,' a reference to India found in the Mahabharata, has been in existence in this country from thousands of years. "Not only Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Sikhism which are the native religions but also Christianity and Islam have flourished here. Religious tolerance is inherent in Indian tradition," the Dalai Lama said.[21]

Freedom of religion in the Indian subcontinent is exemplified by the reign of King Piyadasi (304–232 BC) (Ashoka). One of King Ashoka's main concerns was to reform governmental institutes and exercise moral principles in his attempt to create a just and humane society. Later he promoted the principles of Buddhism, and the creation of a just, understanding and fair society was held as an important principle for many ancient rulers of this time in the East.

The importance of freedom of worship in India was encapsulated in an inscription of Ashoka:

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

King Piyadasi (Ashok) dear to the Gods, honours all sects, the ascetics (hermits) or those who dwell at home, he honours them with charity and in other ways. But the King, dear to the Gods, attributes less importance to this charity and these honours than to the vow of seeing the reign of virtues, which constitutes the essential part of them. For all these virtues there is a common source, modesty of speech. That is to say, one must not exalt one's creed discrediting all others, nor must one degrade these others without legitimate reasons. One must, on the contrary, render to other creeds the honour befitting them.

On the main Asian continent, the Mongols were tolerant of religions. People could worship as they wished freely and openly.

After the arrival of Europeans, Christians in their zeal to convert local as per belief in conversion as service of God, have also been seen to fall into frivolous methods since their arrival, though by and large there are hardly any reports of law and order disturbance from mobs with Christian beliefs, except perhaps in the north eastern region of India.[22]

Freedom of religion in contemporary India is a fundamental right guaranteed under Article 25 of the nation's constitution. Accordingly, every citizen of India has a right to profess, practice and propagate their religions peacefully.[23]Vishwa Hindu Parishad counters this argument by saying that evangelical Christians are forcefully (or through money) converting rural, illiterate populations and they are only trying to stop this.

In September 2010, the Indian state of Kerala's State Election Commissioner announced that "Religious heads cannot issue calls to vote for members of a particular community or to defeat the nonbelievers".[24] The Catholic Church comprising Latin, Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara rites used to give clear directions to the faithful on exercising their franchise during elections through pastoral letters issued by bishops or council of bishops. The pastoral letter issued by Kerala Catholic Bishops' Council (KCBC) on the eve of the poll urged the faithful to shun atheists.[24]

Even today, most Indians celebrate all religious festivals with equal enthusiasm and respect. Hindu festivals like Deepavali and Holi, Muslim festivals like Eid al-Fitr, Eid-Ul-Adha, Muharram, Christian festivals like Christmas and other festivals like Buddha Purnima, Mahavir Jayanti, Gur Purab etc. are celebrated and enjoyed by all Indians.

Europe

Religious intolerance

Nineteenth century allegorical statue on the Congress Column in Belgium depicting religious freedom

Most Roman Catholic kingdoms kept a tight rein on religious expression throughout the Middle Ages. Jews were alternately tolerated and persecuted, the most notable examples of the latter being the expulsion of all Jews from Spain in 1492. Some of those who remained and converted were tried as heretics in the Inquisition for allegedly practicing Judaism in secret. Despite the persecution of Jews, they were the most tolerated non-Catholic faith in Europe.

However, the latter was in part a reaction to the growing movement that became the Reformation. As early as 1380, John Wycliffe in England denied transubstantiation and began his translation of the Bible into English. He was condemned in a Papal Bull in 1410, and all his books were burned.

In 1414, Jan Hus, a Bohemian preacher of reformation, was given a safe conduct by the Holy Roman Emperor to attend the Council of Constance. Not entirely trusting in his safety, he made his will before he left. His forebodings proved accurate, and he was burned at the stake on 6 July 1415. The Council also decreed that Wycliffe's remains be disinterred and cast out. This decree was not carried out until 1429.

After the fall of the city of Granada, Spain, in 1492, the Muslim population was promised religious freedom by the Treaty of Granada, but that promise was short-lived. In 1501, Granada's Muslims were given an ultimatum to either convert to Christianity or to emigrate. The majority converted, but only superficially, continuing to dress and speak as they had before and to secretly practice Islam. The Moriscos (converts to Christianity) were ultimately expelled from Spain between 1609 (Castile) and 1614 (rest of Spain), by Philip III.

Martin Luther published his famous 95 Theses in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517. His major aim was theological, summed up in the three basic dogmas of Protestantism:

- The Bible only is infallible.

- Every Christian can interpret it.

- Human sins are so wrongful that no deed or merit, only God's grace, can lead to salvation.

In consequence, Luther hoped to stop the sale of indulgences and to reform the Church from within. In 1521, he was given the chance to recant at the Diet of Worms before Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. After he refused to recant, he was declared heretic. Partly for his own protection, he was sequestered on the Wartburg in the possessions of Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, where he translated the New Testament into German. He was excommunicated by Papal Bull in 1521.

However, the movement continued to gain ground in his absence and spread to Switzerland. Huldrych Zwingli preached reform in Zürich from 1520 to 1523. He opposed the sale of indulgences, celibacy, pilgrimages, pictures, statues, relics, altars, and organs. This culminated in outright war between the Swiss cantons that accepted Protestantism and the Catholics. The Catholics were victorious, and Zwingli was killed in battle in 1531. The Catholic cantons were magnanimous in victory.[citation needed]

The defiance of Papal authority proved contagious, and in 1533, when Henry VIII of England was excommunicated for his divorce and remarriage to Anne Boleyn, he promptly established a state church with bishops appointed by the crown. This was not without internal opposition, and Thomas More, who had been his Lord Chancellor, was executed in 1535 for opposition to Henry.

In 1535, the Swiss canton of Geneva became Protestant. In 1536, the Bernese imposed the reformation on the canton of Vaud by conquest. They sacked the cathedral in Lausanne and destroyed all its art and statuary. John Calvin, who had been active in Geneva was expelled in 1538 in a power struggle, but he was invited back in 1540.

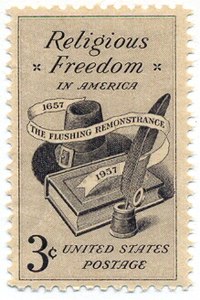

A U.S. postage stamp commemorating religious freedom and the Flushing Remonstrance

The same kind of seesaw back and forth between Protestantism and Catholicism was evident in England when Mary I of England returned that country briefly to the Catholic fold in 1553 and persecuted Protestants. However, her half-sister, Elizabeth I of England was to restore the Church of England in 1558, this time permanently, and began to persecute Catholics again. The King James Bible commissioned by King James I of England and published in 1611 proved a landmark for Protestant worship, with official Catholic forms of worship being banned.

In France, although peace was made between Protestants and Catholics at the Treaty of Saint Germain in 1570, persecution continued, most notably in the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew's Day on 24 August 1572, in which thousands of Protestants throughout France were killed. A few years before, at the "Michelade" of Nîmes in 1567, Protestants had massacred the local Catholic clergy.

Early steps and attempts in the way of tolerance

The cross of the war memorial and a menorah coexist in Oxford, Oxfordshire, England

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily under Roger II was characterized by its multi-ethnic nature and religious tolerance. Normans, Jews, Muslim Arabs, Byzantine Greeks, Lombards, and native Sicilians lived in harmony.[25][26][not in citation given] Rather than exterminate the Muslims of Sicily, Roger II's grandson Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1215–1250) allowed them to settle on the mainland and build mosques. Not least, he enlisted them in his – Christian – army and even into his personal bodyguards.[27][need quotation to verify][28][need quotation to verify]

Bohemia (present-day Czech Republic) enjoyed religious freedom between 1436 and 1520, and became one of the most liberal countries of the Christian world during that period of time. The so-called Basel Compacts of 1436 declared the freedom of religion and peace between Catholics and Utraquists. In 1609 Emperor Rudolf II granted Bohemia greater religious liberty with his Letter of Majesty. The privileged position of the Catholic Church in the Czech kingdom was firmly established after the Battle of White Mountain in 1620. Gradually freedom of religion in Bohemian lands came to an end and Protestants fled or were expelled from the country. A devout Catholic, Emperor Ferdinand II forcibly converted Austrian and Bohemian Protestants.[citation needed]

In the meantime, in Germany Philip Melanchthon drafted the Augsburg Confession as a common confession for the Lutherans and the free territories. It was presented to Charles V in 1530.

In the Holy Roman Empire, Charles V agreed to tolerate Lutheranism in 1555 at the Peace of Augsburg. Each state was to take the religion of its prince, but within those states, there was not necessarily religious tolerance. Citizens of other faiths could relocate to a more hospitable environment.

In France, from the 1550s, many attempts to reconcile Catholics and Protestants and to establish tolerance failed because the State was too weak to enforce them. It took the victory of prince Henry IV of France, who had converted into Protestantism, and his accession to the throne, to impose religious tolerance formalized in the Edict of Nantes in 1598. It would remain in force for over 80 years until its revocation in 1685 by Louis XIV of France. Intolerance remained the norm until Louis XVI, who signed the Edict of Versailles (1787), then the constitutional text of 24 December 1789, granting civilian rights to Protestants. The French Revolution then abolished state religion and confiscated all Church property, turning intolerance against Catholics.[citation needed]

Early laws and legal guarantees for religious freedom

Principality of Transylvania

In 1558, the Transylvanian Diet's Edict of Torda declared free practice of both Catholicism and Lutheranism. Calvinism, however, was prohibited. Calvinism was included among the accepted religions in 1564. Ten years after the first law, in 1568, the same Diet, under the chairmanship of King of Hungary, and Prince of Transylvania John Sigismund Zápolya (John II.),[29] following the teaching of Ferenc Dávid,[30] the founder of the Unitarian Church of Transylvania,[31] extended the freedom to all religions, declaring that "It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expelling for his religion". However, it was more than a religious tolerance; it declared the equality of the religions, prohibiting all kinds of acts from authorities or from simple people, which could harm other groups or people because of their religious beliefs. The emergence in social hierarchy wasn't dependent on the religion of the person thus Transylvania had also Catholic and Protestant monarchs, who all respected the Edict of Torda. The lack of state religion was unique for centuries in Europe. Therefore, the Edict of Torda is considered as the first legal guarantee of religious freedom in Christian Europe.[32]

Declaration, by Ferenc Dávid of Religious and Conscience Freedom in the Diet of Torda in 1568, painting by Aladár Körösfői-Kriesch

Act of Religious Tolerance and Freedom of Conscience:

His majesty, our Lord, in what manner he – together with his realm – legislated in the matter of religion at the previous Diets, in the same matter now, in this Diet, reaffirms that in every place the preachers shall preach and explain the Gospel each according to his understanding of it, and if the congregation like it, well. If not, no one shall compel them for their souls would not be satisfied, but they shall be permitted to keep a preacher whose teaching they approve. Therefore none of the superintendents or others shall abuse the preachers, no one shall be reviled for his religion by anyone, according to the previous statutes, and it is not permitted that anyone should threaten anyone else by imprisonment or by removal from his post for his teaching. For faith is the gift of God and this comes from hearing, which hearings is by the word of God.— Diet at Torda, 1568 : King John Sigismund[33]

Four religions (Catholicism, Lutheranism, Calvinism, Unitarianism) were named as accepted religions (religo recepta), having their representatives in the Transylvanian Diet, while the other religions, like the Orthodoxs, Sabbatarians and Anabaptists were tolerated churches (religio tolerata), which meant that they had no power in the law making and no veto rights in the Diet, but they were not persecuted in any way. Thanks to the Edict of Torda, from the last decades of the 16th Century Transylvania was the only place in Europe, where so many religions could live together in harmony and without persecution.[34]

This religious freedom ended however for some of the religions of Transylvania in 1638. After this year the Sabbatarians begun to be persecuted, and forced to convert to one of the accepted religions of Transylvania.[35]

Habsburg rule in Transylvania

Also the Unitarians (despite of being one of the "accepted religions") started to be put under an ever-growing pressure, which culminated after the Habsburg conquest of Transylvania (1691),[36] Also after the Habsburg occupation, the new Austrian masters forced in the middle of the 18th century the Hutterite Anabaptists (who found a safe heaven in 1621 in Transylvania, after the persecution to which they were subjected in the Austrian provinces and Moravia) to convert to Catholicism or to migrate in another country, which finally the Anabaptists did, leaving Transylvania and Hungary for Wallachia, than from there to Russia, and finally in the United States.[37]

Netherlands

In the Union of Utrecht (20 January 1579), personal freedom of religion was declared in the struggle between the Northern Netherlands and Spain. The Union of Utrecht was an important step in the establishment of the Dutch Republic (from 1581 to 1795). Under Calvinist leadership, the Netherlands became the most tolerant country in Europe. It granted asylum to persecuted religious minorities, such as the Huguenots, the Dissenters, and the Jews who had been expelled from Spain and Portugal.[38] The establishment of a Jewish community in the Netherlands and New Amsterdam (present-day New York) during the Dutch Republic is an example of religious freedom. When New Amsterdam surrendered to the English in 1664, freedom of religion was guaranteed in the Articles of Capitulation. It benefitted also the Jews who had landed on Manhattan Island in 1654, fleeing Portuguese persecution in Brazil. During the 18th century, other Jewish communities were established at Newport, Rhode Island, Philadelphia, Charleston, Savannah, and Richmond.[39]

Intolerance of dissident forms of Protestantism also continued, as evidenced by the exodus of the Pilgrims, who sought refuge, first in the Netherlands, and ultimately in America, founding Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts in 1620. William Penn, the founder of Philadelphia, was involved in a case which had a profound effect upon future American laws and those of England. In a classic case of jury nullification, the jury refused to convict William Penn of preaching a Quaker sermon, which was illegal. Even though the jury was imprisoned for their acquittal, they stood by their decision and helped establish the freedom of religion.[citation needed]

Poland

Original act of the Warsaw Confederation 1573. The beginning of religious freedom in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The General Charter of Jewish Liberties known as the Statute of Kalisz was issued by the Duke of Greater Poland Boleslaus the Pious on 8 September 1264 in Kalisz. The statute served as the basis for the legal position of Jews in Poland and led to the creation of the Yiddish-speaking autonomous Jewish nation until 1795. The statute granted exclusive jurisdiction of Jewish courts over Jewish matters and established a separate tribunal for matters involving Christians and Jews. Additionally, it guaranteed personal liberties and safety for Jews including freedom of religion, travel, and trade. The statute was ratified by subsequent Polish Kings: Casimir III of Poland in 1334, Casimir IV of Poland in 1453 and Sigismund I of Poland in 1539. Poland freed Jews from direct royal authority, opening up enormous administrative and economic opportunities to them.[40]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The right to worship freely was a basic right given to all inhabitants of the future Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth throughout the 15th and early 16th century, however, complete freedom of religion was officially recognized in 1573 during the Warsaw Confederation. Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth kept religious freedom laws during an era when religious persecution was an everyday occurrence in the rest of Europe.[41]

United States

Most of the early colonies were generally not tolerant of dissident forms of worship, with Maryland being one of the exceptions. For example, Roger Williams found it necessary to found a new colony in Rhode Island to escape persecution in the theocratically dominated colony of Massachusetts. The Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were the most active of the New England persecutors of Quakers, and the persecuting spirit was shared by Plymouth Colony and the colonies along the Connecticut river.[42] In 1660, one of the most notable victims of the religious intolerance was English Quaker Mary Dyer, who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony.[42] As one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs, the hanging of Dyer on the Boston gallows marked the beginning of the end of the Puritan theocracy and New England independence from English rule, and in 1661 King Charles II explicitly forbade Massachusetts from executing anyone for professing Quakerism.[43] Anti-Catholic sentiment appeared in New England with the first Pilgrim and Puritan settlers.[44] In 1647, Massachusetts passed a law prohibiting any Jesuit Roman Catholic priests from entering territory under Puritan jurisdiction.[45] Any suspected person who could not clear himself was to be banished from the colony; a second offense carried a death penalty.[46] The Pilgrims of New England held radical Protestant disapproval of Christmas.[47] Christmas observance was outlawed in Boston in 1659.[48] The ban by the Puritans was revoked in 1681 by an English appointed governor, however it was not until the mid-19th century that celebrating Christmas became common in the Boston region.[49]

Freedom of religion was first applied as a principle of government in the founding of the colony of Maryland, founded by the Catholic Lord Baltimore, in 1634.[50] Fifteen years later (1649), the Maryland Toleration Act, drafted by Lord Baltimore, provided: "No person or persons...shall from henceforth be any waies troubled, molested or discountenanced for or in respect of his or her religion nor in the free exercise thereof." The Act allowed freedom of worship for all Trinitarian Christians in Maryland, but sentenced to death anyone who denied the divinity of Jesus. The Maryland Toleration Act was repealed during the Cromwellian Era with the assistance of Protestant assemblymen and a new law barring Catholics from openly practicing their religion was passed.[51] In 1657, the Catholic Lord Baltimore regained control after making a deal with the colony's Protestants, and in 1658 the Act was again passed by the colonial assembly. This time, it would last more than thirty years, until 1692[52] when, after Maryland's Protestant Revolution of 1689, freedom of religion was again rescinded.[50][53] In addition, in 1704, an Act was passed "to prevent the growth of Popery in this Province", preventing Catholics from holding political office.[53] Full religious toleration would not be restored in Maryland until the American Revolution, when Maryland's Charles Carroll of Carrollton signed the American Declaration of Independence.

Rhode Island (1636), Connecticut (1636), New Jersey, and Pennsylvania (1682) – founded by Protestants Roger Williams, Thomas Hooker, and William Penn, respectively – combined the democratic form of government which had been developed by the Puritans and the Separatist Congregationalists in Massachusetts with religious freedom.[54][55][56][57] These colonies became sanctuaries for persecuted religious minorities. Catholics and later on Jews also had full citizenship and free exercise of their religions.[58][59][60] Williams, Hooker, Penn, and their friends were firmly convinced that freedom of conscience was the will of God. Williams gave the most profound argument: As faith is the free work of the Holy Spirit, it cannot be forced on a person. Therefore, strict separation of church and state has to be kept.[61] Pennsylvania was the only colony that retained unlimited religious freedom until the foundation of the United States in 1776. It was the inseparable connection between democracy, religious freedom, and the other forms of freedom which became the political and legal basis of the new nation. In particular, Baptists and Presbyterians demanded the disestablishment of state churches – Anglican and Congregationalist – and the protection of religious freedom.[62]

Reiterating Maryland's and the other colonies' earlier colonial legislation, the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, written in 1779 by Thomas Jefferson, proclaimed:

[N]o man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.

Those sentiments also found expression in the First Amendment of the national constitution, part of the United States' Bill of Rights: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof..."

The United States formally considers religious freedom in its foreign relations. The International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 established the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom which investigates the records of over 200 other nations with respect to religious freedom, and makes recommendations to submit nations with egregious records to ongoing scrutiny and possible economic sanctions. Many human rights organizations have urged the United States to be still more vigorous in imposing sanctions on countries that do not permit or tolerate religious freedom.

Canada

Freedom of religion in Canada is a constitutionally protected right, allowing believers the freedom to assemble and worship without limitation or interference. Canadian law goes further, requiring that private citizens and companies provide reasonable accommodation to those, for example, with strong religious beliefs. The Canadian Human Rights Act allows an exception to reasonable accommodation with respect to religious dress, such as a Sikh turban, when there is a bona fide occupational requirement, such as a workplace requiring a hard hat.[63]

International

On 25 November 1981, the United Nations General Assembly passed the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief. This declaration recognizes freedom of religion as a fundamental human right in accordance with several other instruments of international law.[64]

However, the most substantial binding legal instruments that guarantee the right to freedom of religion that was passed by the international community is the Convention on the Rights of the Child which states in its Article 14: "States Parties shall respect the right of the child to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. – States Parties shall respect the rights and duties of the parents and, when applicable, legal guardians, to provide direction to the child in the exercise of his or her right in a manner consistent with the evolving capacities of the child. – Freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health or morals, or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others."[65]

Contemporary debates

| Freedom of religion | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Concepts

| ||||||||||||

Status by country

| ||||||||||||

Religious persecution

| ||||||||||||

Religion portal | ||||||||||||

Theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs

In 1993, the UN's human rights committee declared that article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights "protects theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs, as well as the right not to profess any religion or belief."[66] The committee further stated that "the freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one's current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views." Signatories to the convention are barred from "the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers" to recant their beliefs or convert. Despite this, minority religions still are persecuted in many parts of the world.[67][68]

Liberal secular

Adam Smith argued in favour of freedom of religion.

The French philosopher Voltaire noted in his book on English society, Letters on the English, that freedom of religion in a diverse society was deeply important to maintaining peace in that country. That it was also important in understanding why England at that time was more prosperous in comparison to the country's less religiously tolerant European neighbours.

If one religion only were allowed in England, the Government would very possibly become arbitrary; if there were but two, the people would cut one another’s throats; but as there are such a multitude, they all live happy and in peace.[69]

Adam Smith, in his book The Wealth of Nations (using an argument first put forward by his friend and contemporary David Hume), states that in the long run it is in the best interests of society as a whole and the civil magistrate (government) in particular to allow people to freely choose their own religion, as it helps prevent civil unrest and reduces intolerance. So long as there are enough different religions and/or religious sects operating freely in a society then they are all compelled to moderate their more controversial and violent teachings, so as to be more appealing to more people and so have an easier time attracting new converts. It is this free competition amongst religious sects for converts that ensures stability and tranquillity in the long run.

Smith also points out that laws that prevent religious freedom and seek to preserve the power and belief in a particular religion will, in the long run, only serve to weaken and corrupt that religion, as its leaders and preachers become complacent, disconnected and unpractised in their ability to seek and win over new converts:[70]

The interested and active zeal of religious teachers can be dangerous and troublesome only where there is either but one sect tolerated in the society, or where the whole of a large society is divided into two or three great sects; the teachers of each acting by concert, and under a regular discipline and subordination. But that zeal must be altogether innocent, where the society is divided into two or three hundred, or, perhaps, into as many thousand small sects, of which no one could be considerable enough to disturb the public tranquillity. The teachers of each sect, seeing themselves surrounded on all sides with more adversaries than friends, would be obliged to learn that candour and moderation which are so seldom to be found among the teachers of those great sects.[71]

Hinduism

Hinduism is one of the more broad-minded religions when it comes to religious freedom.[72] It respects the right of everyone to reach God in their own way. Hindus believe in different ways to preach attainment of God and religion as a philosophy and hence respect all religions as equal. One of the famous Hindu sayings about religion is: "Truth is one; sages call it by different names."[72]

Judaism

Women detained at Western Wall for wearing prayer shawls; photo from Women of the Wall

Judaism includes multiple streams, such as Orthodox, Reform Judaism, Conservative Judaism, Reconstructionist Judaism, Jewish Renewal and Humanistic Judaism. However, Judaism also exists in many forms as a civilization, possessing characteristics known as peoplehood, rather than strictly as a religion.[73] In the Torah, Jews are forbidden to practice idolatry and are commanded to root out pagan and idolatrous practices within their midst, including killing idolaters who sacrifice children to their gods, or engage in immoral activities. However, these laws are not adhered to anymore as Jews have usually lived among a multi-religious community.

After the conquest of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judea by the Roman Empire, a Jewish state did not exist until 1948 with the establishment of the State of Israel. For over 1500 years Jewish people lived under pagan, Christian, Muslim, etc. rule. As such Jewish people in some of these states faced persecution. From the pogroms in Europe during the Middle Ages to the establishment of segregated Jewish ghettos during World War II. In the Middle East, Jews were categorised as dhimmi, non- Muslims permitted to live within a Muslim state. Even though given rights within a Muslim state, a dhimmi is still not equal to a Muslim within Muslim society, the same way non-Jewish Israeli citizens are not equal with Jewish citizens in modern-day Israel.

Possibly because of this history of long term persecution, Jews in modernity have been among the most active proponents of religious freedom in the US and abroad and have founded and supported anti-hate institutions, including the Anti-Defamation League, the Southern Poverty Law Center and the American Civil Liberties Union. Jews are very active in supporting Muslim and other religious groups in the US against discrimination and hate crimes and most Jewish congregations throughout the US and many individual Jews participate in interfaith community projects and programs.

The State of Israel was established for the Jewish diaspora after World War II. While the Israel Declaration of Independence stresses religious freedom as a fundamental principle, in practice the current[timeframe?] government, dominated by the ultra-Orthodox segment of the population has instituted legal barriers for those who do not practice Orthodox Judaism as Jews. However, as a nation state, Israel is very open towards other religions and religious practices, including public Muslim call to prayer chants and Christian prayer bells ringing in Jerusalem. Israel has been evaluated in research by the Pew organization as having "high" government restrictions on religion. The government recognizes only Orthodox Judaism in certain matters of personal status, and marriages can only be performed by religious authorities. The government provides the greatest funding to Orthodox Judaism, even though adherents represent a minority of citizens.[74] Jewish women, including Anat Hoffman, have been arrested at the Western Wall for praying and singing while wearing religious garments the Orthodox feel should be reserved for men. Women of the Wall have organized to promote religious freedom at the Wall.[75] In November 2014, a group of 60 non-Orthodox rabbinical students were told they would not be allowed to pray in the Knesset synagogue because it is reserved for Orthodox. Rabbi Joel Levy, director of the Conservative Yeshiva in Jerusalem, said that he had submitted the request on behalf of the students and saw their shock when the request was denied. He noted: "paradoxically, this decision served as an appropriate end to our conversation about religion and state in Israel." MK Dov Lipman expressed the concern that many Knesset workers are unfamiliar with non-Orthodox and American practices and would view "an egalitarian service in the synagogue as an affront."[76] The non-Orthodox forms of Jewish practice function independently in Israel, except for these issues of praying at the Western Wall.

Christianity

Part of the Oscar Straus Memorial in Washington, D.C. honoring the right to worship

According to the Catholic Church in the Vatican II document on religious freedom, Dignitatis Humanae, "the human person has a right to religious freedom", which is described as "immunity from coercion in civil society".[77] This principle of religious freedom "leaves untouched traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty of men and societies toward the true religion."[77] In addition, this right "is to be recognized in the constitutional law whereby society is governed and thus it is to become a civil right."[77]

Prior to this, Pope Pius IX had written a document called the Syllabus of Errors. The Syllabus was made up of phrases and paraphrases from earlier papal documents, along with index references to them, and presented as a list of "condemned propositions". It does not explain why each particular proposition is wrong, but it cites earlier documents to which the reader can refer for the Pope's reasons for saying each proposition is false. Among the statements included in the Syllabus are: "[It is an error to say that] Every man is free to embrace and profess that religion which, guided by the light of reason, he shall consider true" (15); "[It is an error to say that] In the present day it is no longer expedient that the Catholic religion should be held as the only religion of the State, to the exclusion of all other forms of worship"; "[It is an error to say that] Hence it has been wisely decided by law, in some Catholic countries, that persons coming to reside therein shall enjoy the public exercise of their own peculiar worship".[78]

Some Orthodox Christians, especially those living in democratic countries, support religious freedom for all, as evidenced by the position of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Many Protestant Christian churches, including some Baptists, Churches of Christ, Seventh-day Adventist Church and main line churches have a commitment to religious freedoms. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints also affirms religious freedom.[79]

However others, such as African scholar Makau Mutua, have argued that Christian insistence on the propagation of their faith to native cultures as an element of religious freedom has resulted in a corresponding denial of religious freedom to native traditions and led to their destruction. As he states in the book produced by the Oslo Coalition on Freedom of Religion or Belief, "Imperial religions have necessarily violated individual conscience and the communal expressions of Africans and their communities by subverting African religions."[80][81]

In their book Breaking India, Rajiv Malhotra and Aravindan Neelakandan discussed the "US Church" funding activities in India, such as the popularly advertised campaigns to "save" poor children by feeding, clothing, and educating them, with the book arguing that the funds collected were being used not so much for the purposes indicated to sponsors, but for indoctrination and conversion activities. They suggest that India is the prime target of a huge enterprise – a "network" of organizations, individuals, and churches – that, they argue, seem intensely devoted to the task of creating a separatist identity, history, and even religion for the vulnerable sections of India. They suggest that this nexus of players includes not only church groups, government bodies, and related organizations, but also private think tanks and academics.[82]

Joel Spring has written about the Christianization of the Roman Empire:

Christianity added new impetus to the expansion of empire. Increasing the arrogance of the imperial project, Christians insisted that the Gospels and the Church were the only valid sources of religious beliefs. Imperialists could claim that they were both civilizing the world and spreading the true religion. By the 5th century, Christianity was thought of as co-extensive with the Imperium romanum. This meant that to be human, as opposed to being a natural slave, was to be "civilized" and Christian. Historian Anthony Pagden argues, "just as the civitas; had now become coterminous with Christianity, so to be human – to be, that is, one who was 'civil', and who was able to interpret correctly the law of nature – one had now also to be Christian." After the fifteenth century, most Western colonialists rationalized the spread of empire with the belief that they were saving a barbaric and pagan world by spreading Christian civilization.[83]

Islam

Conversion to Islam is simple, but Muslims are forbidden to convert from Islam to another religion. Certain Muslim-majority countries are known for their restrictions on religious freedom, highly favoring Muslim citizens over non-Muslim citizens. Other countries[who?] having the same restrictive laws tend to be more liberal when imposing them. Even other Muslim-majority countries are secular and thus do not regulate religious belief.[84][not in citation given]

In addition, Quran 5:3, which is believed to be God's final revelation to Muhammad, states that Muslims are to fear God and not those who reject Islam, and Quran 53:38–39 states that one is accountable only for one's own actions.[non-primary source needed] Therefore, it postulates that in Islam, in the matters of practising a religion, it does not relate to a worldly punishment, but rather these actions are accountable to God in the afterlife. Thus, this supports the argument against the execution of apostates in Islam.[85][unreliable source?]

However, on the other hand, some Muslims support the practice of executing apostates who leave Islam, as in Bukhari:V4 B52 N260; "The Prophet said, 'If a Muslim discards his religion and separates from the main body of Muslims, kill him.'".

In Iran, the constitution recognizes four religions whose status is formally protected: Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.[86]

The constitution, however, also set the groundwork for the institutionalized persecution of Bahá'ís,[87]

who have been subjected to arrests, beatings, executions, confiscation and destruction of property, and the denial of civil rights and liberties, and the denial of access to higher education.[86] There is no freedom of conscience in Iran, as converting from Islam to any other religion is forbidden.

In Egypt, a 16 December 2006 judgment of the Supreme Administrative Council created a clear demarcation between recognized religions – Islam, Christianity and Judaism – and all other religious beliefs;[88][89] no other religious affiliation is officially admissible.[90] The ruling leaves members of other religious communities, including Bahá'ís, without the ability to obtain the necessary government documents to have rights in their country, essentially denying them of all rights of citizenship.[90] They cannot obtain ID cards, birth certificates, death certificates, marriage or divorce certificates, and passports; they also cannot be employed, educated, treated in public hospitals or vote, among other things.[90] See Egyptian identification card controversy.

Changing religion

Among the most contentious areas of religious freedom is the right of an individual to change or abandon his or her own religion (apostasy), and the right to evangelize individuals seeking to convince others to make such a change.

Other debates have centered around restricting certain kinds of missionary activity by religions. Many Islamic states, and others such as China, severely restrict missionary activities of other religions. Greece, among European countries, has generally looked unfavorably on missionary activities of denominations others than the majority church and proselytizing is constitutionally prohibited.[91]

A different kind of critique of the freedom to propagate religion has come from non-Abrahamic traditions such as the African and Indian. African scholar Makau Mutua criticizes religious evangelism on the ground of cultural annihilation by what he calls "proselytizing universalist faiths" (Chapter 28: Proselytism and Cultural Integrity, p. 652):

...the (human) rights regime incorrectly assumes a level playing field by requiring that African religions compete in the marketplace of ideas. The rights corpus not only forcibly imposes on African religions the obligation to compete – a task for which as nonproselytizing, noncompetitive creeds they are not historically fashioned – but also protects the evangelizing religions in their march towards universalization ... it seems inconceivable that the human rights regime would have intended to protect the right of certain religions to destroy others.[92]

Some Indian scholars[93] have similarly argued that the right to propagate religion is not culturally or religiously neutral.

In Sri Lanka, there have been debates regarding a bill on religious freedom that seeks to protect indigenous religious traditions from certain kinds of missionary activities. Debates have also occurred in various states of India regarding similar laws, particularly those that restrict conversions using force, fraud or allurement.

In 2008, Christian Solidarity Worldwide, a Christian human rights non-governmental organisation which specializes in religious freedom, launched an in-depth report on the human rights abuses faced by individuals who leave Islam for another religion. The report is the product of a year long research project in six different countries. It calls on Muslim nations, the international community, the UN and the international media to resolutely address the serious violations of human rights suffered by apostates.[94]

Apostasy in Islam

Legal opinion on apostasy by the Fatwa committee at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, the highest Islamic institution in the world, concerning the case of a man who converted to Christianity: "Since he left Islam, he will be invited to express his regret. If he does not regret, he will be killed pertaining to rights and obligations of the Islamic law."

In Islam, apostasy is called "ridda" ("turning back") and is considered to be a profound insult to God. A person born of Muslim parents that rejects Islam is called a "murtad fitri" (natural apostate), and a person that converted to Islam and later rejects the religion is called a "murtad milli" (apostate from the community).[95]

In Islamic law (Sharia), the consensus view is that a male apostate must be put to death unless he suffers from a mental disorder or converted under duress, for example, due to an imminent danger of being killed. A female apostate must be either executed, according to Shafi'i, Maliki, and Hanbali schools of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), or imprisoned until she reverts to Islam as advocated by the Sunni Hanafi school and by Shi'a scholars.[96]

Ideally, the one performing the execution of an apostate must be an imam.[96] At the same time, all schools of Islamic jurisprudence agree that any Muslim can kill an apostate without punishment.[97]

However, while almost all scholars agree about the punishment, many disagree on the allowable time to retract the apostasy. Many scholars push this as far as allowing the apostate till he/she dies. Thus, practically making the death penalty just a theoretical statement/exercise.[citation needed] S. A. Rahman, a former Chief Justice of Pakistan, argues that there is no indication of the death penalty for apostasy in the Qur'an.[98]

Secular law

Religious practice may also conflict with secular law, creating debates on religious freedom. For instance, even though polygamy is permitted in Islam, it is prohibited in secular law in many countries. This raises the question of whether prohibiting the practice infringes on the beliefs of certain Muslims. The US and India, both constitutionally secular nations, have taken two different views of this. In India, polygamy is permitted, but only for Muslims, under Muslim Personal Law. In the US, polygamy is prohibited for all. This was a major source of conflict between the early LDS Church and the United States until the Church amended its position on practicing polygamy.

Similar issues have also arisen in the context of the religious use of psychedelic substances by Native American tribes in the United States as well as other Native practices.

In 1955, Chief Justice of California Roger J. Traynor neatly summarized the American position on how freedom of religion cannot imply freedom from law: "Although freedom of conscience and the freedom to believe are absolute, the freedom to act is not."[99] But with respect to the religious use of animals within secular law and those acts, the US Supreme Court decision in the case of the Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah in 1993 upheld the right of Santeria adherents to practice ritual animal sacrifice, with Justice Anthony Kennedy stating in the decision: "religious beliefs need not be acceptable, logical, consistent or comprehensible to others in order to merit First Amendment protection" (quoted by Justice Kennedy from the opinion by Justice Burger in Thomas v. Review Board of the Indiana Employment Security Division 450 U.S. 707 (1981)).[100]

In 2015, Kim Davis, a Kentucky county clerk, refused to abide by the Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges legalizing Same-sex marriage in the United States. When she refused to issue marriage licenses, she became embroiled in the Miller v. Davis lawsuit. Her actions caused attorney and author Roberta Kaplan to state that "Kim Davis is the clearest example of someone who wants to use a religious liberty argument to discriminate."[101]

In 1962, the case of Engele v. Vitale went to court over the violation of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment resulting from a mandatory nondenominational prayer in New York public schools. The Supreme Court ruled in opposition to the state.[102]

In 1963, the Supreme Court ruled on the case of Abington School District v. Schempp. Edward Schempp sued the school district in Abington over the Pennsylvania law which required students to hear and sometimes read portions of the bible for their daily education. The court ruled in favor of Schempp and the Pennsylvania law was overturned.[103]

In 1968, the Supreme Court ruled on the case of Epperson v. Arkansas. Susan Epperson, a high school teacher in Arkansas sued over a violation of religious freedom. The state had a law banning the teaching of evolution and the school Epperson worked for had provided curriculum which contained evolutionary theory. Epperson had to choose between violating the law or losing her job. The Supreme Court ruled to overturn the Arkansas law because it was unconstitutional.[104]

Children's rights

The law in Germany provides the term of "religious majority" (Religiöse Mündigkeit) with a minimum age for minors to follow their own religious beliefs even if their parents don't share those or don't approve. Children 14 and older have the unrestricted right to enter or exit any religious community. Children 12 and older cannot be compelled to change to a different belief. Children 10 and older have to be heard before their parents change their religious upbringing to a different belief.[105] There are similar laws in Austria[106] and in Switzerland.[107]

International Religious Freedom Day

27 October is International Religious Freedom Day, in commemoration of the execution of the Boston martyrs, a group of Quakers executed by the Puritans on Boston Common for their religious beliefs under the legislature of the Massachusetts Bay Colony between 1659–1661.[108] The US proclaimed 16 January Religious Freedom Day.[109]

Modern concerns

In its 2011 annual report, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom designated fourteen nations as "countries of particular concern". The commission chairman commented that these are nations whose conduct marks them as the world's worst religious freedom violators and human rights abusers. The fourteen nations designated were Burma, China, Egypt, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, North Korea, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam. Other nations on the commission's watchlist include Afghanistan, Belarus, Cuba, India, Indonesia, Laos, Russia, Somalia, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Venezuela.[110]

There are concerns about the restrictions on public religious dress in some European countries (including the Hijab, Kippah, and Christian cross).[111][112] Article 18 of the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights limits restrictions on freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs to those necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.[113] Freedom of religion as a legal concept is related to, but not identical with, religious toleration, separation of church and state, or secular state (laïcité).

Social hostilities and government restrictions

Freedom of religion by country (Pew Research Center study, 2009). Light yellow: low restriction; red: very high restriction on freedom of religion.

The Pew Research Center has performed studies on international religious freedom between 2009 and 2015, compiling global data from 16 governmental and non-governmental organizations–including the United Nations, the United States State Department, and Human Rights Watch–and representing over 99.5 percent of the world's population.[114][115] In 2009, nearly 70 percent of the world's population lived in countries classified as having heavy restrictions on freedom of religion.[114][115] This concerns restrictions on religion originating from government prohibitions on free speech and religious expression as well as social hostilities undertaken by private individuals, organisations and social groups. Social hostilities were classified by the level of communal violence and religion-related terrorism.

While most countries provided for the protection of religious freedom in their constitutions or laws, only a quarter of those countries were found to fully respect these legal rights in practice. In 75 countries governments limit the efforts of religious groups to proselytise and in 178 countries religious groups must register with the government. In 2013, Pew classified 30% of countries as having restrictions that tend to target religious minorities, and 61% of countries have social hostilities that tend to target religious minorities.[116]

The countries in North and South America reportedly had some of the lowest levels of government and social restrictions on religion, while The Middle East and North Africa were the regions with the highest. Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Iran were the countries that top the list of countries with the overall highest levels of restriction on religion. Topping the Pew government restrictions index were Saudi Arabia, Iran, Uzbekistan, China, Egypt, Burma, Maldives, Eritrea, Malaysia and Brunei.

Of the world's 25 most populous countries, Iran, Egypt, Indonesia and Pakistan had the most restrictions, while Brazil, Japan, Italy, South Africa, the UK, and the US had some of the lowest levels, as measured by Pew.

Vietnam and China were classified as having high government restrictions on religion but were in the moderate or low range when it came to social hostilities. Nigeria, Bangladesh and India were high in social hostilities but moderate in terms of government actions.

Restrictions on religion across the world increased between mid-2009 and mid-2010, according to a 2012 study by the Pew Research Center. Restrictions in each of the five major regions of the world increased—including in the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa, the two regions where overall restrictions previously had been declining. In 2010, Egypt, Nigeria, the Palestinian territories, Russia, and Yemen were added to the "very high" category of social hostilities.[117] The five highest social hostility scores were for Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Iraq, and Bangladesh.[118] In 2015, Pew published that social hostilities declined in 2013, but the harassment of Jews increased.[116]

See also

- Edict of toleration

- Freedom of thought

- International Association for Religious Freedom

- International Center for Law and Religion Studies

- International Coalition for Religious Freedom

- International Religious Liberty Association

- North American Religious Liberty Association

- Religious conversion

- Religious discrimination

- Religious freedom bill

- Status of religious freedom by country

- Religious education in primary and secondary education

References

^ "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights". The United Nations.

^ Davis, Derek H. "The Evolution of Religious Liberty as a Universal Human Right". Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

^ Congressional Record #29734 – 19 November 2003. Google Books. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ Cyrus Cylinder, livius.org.

^ Richard A. Taylor; E. Ray Clendenen (15 October 2004). Haggai, Malachi. B&H Publishing Group. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-8054-0121-9.

^ Njeuma, Martin Z. (2012). Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902. African Books Collective. p. 82. ISBN 978-9956-726-95-0.Of all the various forms of taxation known to Islamic communities, it seems only two – the zakat and the jixya were of importance in Adamawa. [...] The jizya was the levy on non-Muslim peoples who surrendered to Islam and were given the status dhimmi

^ H. Patrick Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World. Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 219.

^ The French scholar Gustave Le Bon (the author of La civilisation des Arabes) writes "that despite the fact that the incidence of taxation fell more heavily on a Muslim than a non-Muslim, the non-Muslim was free to enjoy equally well with every Muslim all the privileges afforded to the citizens of the state. The only privilege that was reserved for the Muslims was the seat of the caliphate, and this, because of certain religious functions attached to it, which could not naturally be discharged by a non-Muslim." Mun'im Sirry (2014), Scriptural Polemics: The Qur'an and Other Religions, p.179. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199359363.

^ Abou El Fadl, Khaled (2007). The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from the Extremists. HarperOne. p. 204. ISBN 978-0061189036.According the dhimma status system, non-Muslims must pay a poll tax in return for Muslim protection and the privilege of living in Muslim territory. Per this system, non-Muslims are exempt from military service, but they are excluded from occupying high positions that involve dealing with high state interests, like being the president or prime minister of the country. In Islamic history, non-Muslims did occupy high positions, especially in matters that related to fiscal policies or tax collection.

^ Weeramantry, C. G. (1997). Justice Without Frontiers: Furthering human rights. Volume 1. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 90-411-0241-8.

^ Sachedina, Abdulaziz Abdulhussein (2001). The Islamic Roots of Democratic Pluralism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513991-7.

^ Mark R. Cohen (1995). Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-691-01082-X. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

^ al-Qattan, Najwa (1999). "Dhimmis in the Muslim Court: Legal Autonomy and Religious Discrimination". International Journal of Middle East Studies. University of Cambridge. 31 (3): 429–44. doi:10.1017/S0020743800055501. ISSN 0020-7438.

^ Sherman A. Jackson (2005). Islam and the Blackamerican: looking toward the third resurrection. Oxford University Press. p. 144. ISBN 0-19-518081-X. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

^ A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility ISBN 0-8050-7932-7

^ Granada by Richard Gottheil, Meyer Kayserling, Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906 ed.

^ "The Jews of Morocco".

^ Who are the Jews of India? – The S. Mark Taper Foundation imprint in Jewish studies. University of California Press. 2000. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-520-21323-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZWX6pF2PTJwC&pg=PA26.; "When the Portuguese arrived in 1498, they brought a spirit of intolerance utterly alien to India. They soon established an Office of Inquisition at Goa, and at their hands Indian Jews experienced the only instance of anti-Semitism ever to occur in Indian soil."

^ David E. Ludden (1996). Contesting the Nation: Religion, Community, and the Politics of Democracy in India. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 257–58. ISBN 0-8122-1585-0.

^ Rajni Kothari (1998). Communalism in Indian Politics. Rainbow Publishers. p. 134. ISBN 978-81-86962-00-8.

^ "India's religious tolerance lauded". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ "Christian Persecution in India: The Real Story". Stephen-knapp.com. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ "The Constitution of India" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ ab "'Using places of worship for campaigning in Kerala civic polls is violation of poll code'". Indian Orthodox Herald. 18 September 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ "Roger II". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 May 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ "Tracing The Norman Rulers of Sicily". New York Times. 26 April 1987. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ Christopher Gravett (15 November 1997). German Medieval Armies 1000–1300. Osprey Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-85532-657-6.

^ Thomas Curtis Van Cleve's The Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen: Immutator Mundi (Oxford, 1972)

^ History of Transylvania. Volume I. From the Beginnings to 1606. Hungarian Research Institute of Canada and A Research Ancillary of the University of Toronto. ISBN 0-88033-479-7. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

^ History of Transylvania. Volume I. From the Beginnings to 1606. Hungarian Research Institute of Canada and A Research Ancillary of the University of Toronto. ISBN 0-88033-479-7. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

^ "Destination Romania/Unitarianism, a religion born in Cluj " Romanian National News Agency (27 Aug 2014)

^ "The Story of Francis David and King John Sigismund: The Establishment of the Transylvanian Unitarian Church". Lightbringers. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

^ Unitarian Universalist Partner Church Council. "Edict of Torda" (DOC). Retrieved on 2008-01-23.

^ "Kovács Kálmán: Erdély és a Habsburg valláspolitika a 17. század utolsó évtizedeiben" Mult-Kor (25 November 2005)

^ History of Transylvania. Volume II. From 1606 to 1830. Hungarian Research Institute of Canada and A Research Ancillary of the University of Toronto. ISBN 0-88033-491-6. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

^ History of Transylvania. Volume II. From 1606 to 1830. Hungarian Research Institute of Canada and A Research Ancillary of the University of Toronto. ISBN 0-88033-491-6. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

^ "Hutterite History Overview". Hutterian Brethren.

^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage (1956), Tübingen (Germany), pp. 396–97

^ Clifton E. Olmstead (1960), History of Religion in the United States, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Ciffs, N.J., p. 124

^ Sinkoff, Nancy (2003). Out of the Shtetl: Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands. Society of Biblical Lit. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-930675-16-2.

^ Zamoyski, Adam. The Polish Way. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1987.

^ ab Rogers, Horatio, 2009. Mary Dyer of Rhode Island: The Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston Common, 1 June 1660 pp. 1–2. BiblioBazaar, LLC.

^ Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: a comprehensive encyclopedia. Google Books. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ "America's dark and not-very-distant history of hating Catholics". The Guardian. 14 June 2016.

^ Pat, Perrin (1 January 1970). Crime and Punishment: The Colonial Period to the New Frontier. Discovery Enterprises. p. 24.

^ Mahoney, Kathleen A. (10 September 2003). Catholic Higher Education in Protestant America: The Jesuits and Harvard in the Age of the University. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 47.

^ Barnett, James Harwood (1984). The American Christmas: A Study in National Culture. Ayer Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 0-405-07671-1.

^ Schnepper, Rachel N. (14 December 2012). "Yuletide's Outlaws". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2012.From 1659 to 1681, anyone caught celebrating Christmas in the colony would be fined five shillings. ...

^ Marling, Karal Ann (2000). Merry Christmas!: Celebrating America's Greatest Holiday. Harvard University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-674-00318-7.

^ ab Zimmerman, Mark, Symbol of Enduring Freedom, p. 19, Columbia Magazine, March 2010.

^ Brugger, Robert J. (1988). Maryland: A Middle Temperament. p 21, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3399-X.

^ Finkelman, Paul, Maryland Toleration Act, The Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties, New York: CRC Press. ISBN 0-415-94342-6.

^ ab Roark, Elisabeth Louise. Artists of Colonial America. p. 78. Retrieved 22 February 2010

^ Christopher Fennell (1998), Plymouth Colony Legal Structure (http://www.histarch.uiuc.edu/plymouth/ccflaw.html)

^ Hanover Historical Texts Project (http://history.hanover.edu/texts/masslib.html)

^ M. Schmidt, Pilgerväter, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Tübingen (Germany), Band V (1961), col. 384

^ M. Schmidt, Hooker, Thomas, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band III (1959), col. 449

^ Clifton E. Olmstead (1960), History of Religion in the United States, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., pp. 74–75, 99, 102–05, 113–15

^ Edwin S. Gaustad (1999), Liberty of Conscience: Roger Williams in America, Judson Press, Valley Forge

^ Hans Fantel (1974), William Penn: Apostel of Dissent, William Morrow & Co., New York, N.Y.

^ Heinrich Bornkamm, Toleranz. In der Geschichte der Christenheit, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band VI (1962), col. 943

^ Robert Middlekauff (2005), The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789, Revised and Expanded Edition, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-531588-2, p. 635

^ Freedom of Religion and Religious Symbols in the Public Sphere. 2.2.2 Headcoverings. Parliament of Canada. Publication No. 2011-60-E. Published 2011-07-25. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

^ "A/RES/36/55. Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief". United Nations. 25 November 1981. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ Religious Rights – International Legal Instruments

^ "CCPR General Comment 22: 30/07/93 on ICCPR Article 18". Minorityrights.org.

^ International Federation for Human Rights (1 August 2003). "Discrimination against religious minorities in Iran" (PDF). fdih.org. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

^ Davis, Derek H. "The Evolution of Religious Liberty as a Universal Human Right" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

^ Voltaire, François Marie Arouet de. (1909–14) [1734]. "Letter VI – On the Presbyterians. Letters on the English". www.bartleby.com. The Harvard Classics. Retrieved 2017-05-25.

^ Smith, Adam (1776), Wealth of Nations, Penn State Electronic Classics edition, republished 2005, pp. 643–49

^ Smith, Adam (1776), Wealth of Nations, Penn State Electronic Classics edition, republished 2005, p. 647

^ ab "Hindu Beliefs". religionfacts.com.

^ Brown, Erica; Galperin, Misha (2009). The Case for Jewish Peoplehood: Can We be One?. Jewish Lights Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-58023-401-6.The 'hood' is not only a geographic reference; it is a shared identity that may be characterized by joint assumptions, body language, certain expressions, and a host of familial-like behaviors that unite an otherwise dispirate groupe of people.

^ "Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life: Global restrictions on Religion (2009" http://www.pewforum.org/files/2009/12/restrictions-fullreport1.pdf

^ "Police arrest 5 women at Western Wall for wearing tallitot" Jerusalem Post (11 April 2013)

^ Maltz, Judy (26 November 2014). "Non-Orthodox Jews prohibited from praying in Knesset synagogue". Haaretz. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

^ abc "Declaration on religious freedom – Dignitatis humanae". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ Pope Pius IX. "The Syllabus". EWTN. , Global Catholic Network

^ "We claim the privilege of worshiping Almighty God according to the dictates of our own conscience, and allow all men the same privilege, let them worship how, where, or what they may", the eleventh Article of Faith.

^ Mutua, Makau. 2004. Facilitating Freedom of Religion or Belief, A Deskbook. Oslo Coalition on Freedom of Religion or Belief.

^ J. D. Van der Vyver; John Witte (1996). Religious human rights in global perspective: legal perspectives. 2. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 418. ISBN 90-411-0177-2.

^ "Introduction". Breaking India.

^ Joel H. Spring (2001). Globalization and educational rights: an intercivilizational analysis. Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8058-3882-4.

^ United States, Department of State. "2010 International Religious Freedom Report". International Religious Freedom Report. US Department of State. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

^ Islam and Belief: At Home with Religious Freedom, Abdullah Saeed (2014): 8.

^ ab

International Federation for Human Rights (1 August 2003). "Discrimination against religious minorities in Iran" (PDF). fdih.org. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

^

Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (2007). "A Faith Denied: The Persecution of the Baha'is of Iran" (PDF). Iran Human Rights Documentation Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-27. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

^ Mayton, Joseph (19 December 2006). "Egypt's Bahais denied citizenship rights". Middle East Times. Archived from the original on 2009-04-02. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

^ Otterman, Sharon (17 December 2006). "Court denies Bahai couple document IDs". The Washington Times. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

^ abc Nkrumah, Gamal (21 December 2006). "Rendered faithless and stateless". Al-Ahram weekly. Archived from the original on 23 January 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

^ "US State Department report on Greece". State.gov. 8 November 2005. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ Mutua, Makau (2004). Facilitating Freedom of Religion or Belief, A Deskbook. Oslo Coalition on Freedom of Religion or Belief. p. 652. ISBN 978-90-04-13783-7.

^ Sanu, Sankrant (2006). "Re-examining Religious Freedom" (PDF). Manushi. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

^ "No place to call home" (PDF). Christian Solidarity Worldwide. 29 April 2008.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2007. from "Leaving Islam: Apostates speak out" by Ibn Warraq

^ ab Heffening, W. "Murtadd". In P.J. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs. Encyclopaedia of Islam Online Edition. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

^ Adbul Qadir Oudah (1999). Kitab Bhavan. New Delhi: Kitab Bhavan. ISBN 81-7151-273-9. , Volume II. pp. 258–62; Volume IV. pp. 19–21

^ S. A. Rahman (2007). "Summary and Conclusions". Punishment of Apostasy in Islam. The Other Press. pp. 132–42. ISBN 978-983-9541-49-6.

^ Pencovic v. Pencovic, 45 Cal. 2d 67 (1955).

^ Criminal Law and Procedure, Daniel E. Hall. Cengage Learning, July 2008. p. 266. [1]

^ Bromberger, Brian (15 October 2015). "New book details Windsor Supreme Court victory". Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

^ "Facts and Case Summary - Engel v. Vitale". United States Courts. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

^ "Abington School District V Schempp - Cases | Laws.com". cases.laws.com. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

^ "Epperson V Arkansas - Cases | Laws.com". cases.laws.com. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

^ "Gesetz über die religiöse Kindererziehung". Bundesrecht.juris.de. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ Bundesgesetz 1985 über die religiöse Kindererziehung (pdf)

^ "Schweizerisches Zivilgesetzbuch Art 303: Religiöse Erziehung". Gesetze.ch. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

^ Margery Post Abbott (2011). Historical Dictionary of the Friends (Quakers). Scarecrow Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8108-7088-8.

^ Religious Freedom Day, 2006 – A Proclamation by the President of the United States of America, Religious Freedom Day, 2001 – Proclamation by the President of the United States of America 15 January 2001

^ "US commission names 14 worst violators of religious freedom". Christianity Today. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.