Ptolemaic Kingdom

Ptolemaic Kingdom Πτολεμαϊκὴ βασιλεία Ptolemaïkḕ basileía | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 305 BC–30 BC | |||||||||||

Eagle of Zeus[1] | |||||||||||

The Ptolemaic Kingdom in 300 BC (in blue) | |||||||||||

| Capital | Alexandria | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Greek (official) Egyptian (common) | ||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Greek religion,[2]ancient Egyptian religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Hellenistic monarchy | ||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||

• 305–283 BC | Ptolemy I Soter (first) | ||||||||||

• 51–30 BC | Cleopatra VII (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||||||||

• Established | 305 BC | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 30 BC | ||||||||||

| Currency | Greek Drachma | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Egypt | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (/ˌtɒlɪˈmeɪ.ɪk/; Koine Greek: Πτολεμαϊκὴ βασιλεία, translit. Ptolemaïkḕ basileía)[3] was a Hellenistic kingdom based in ancient Egypt. It was ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty, which started with Ptolemy I Soter's accession after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and which ended with the death of Cleopatra and the Roman conquest in 30 BC.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom was founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter, a diadochus originally from Macedon in northern Greece who declared himself pharaoh of Egypt and created a powerful Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled an area stretching from southern Syria to Cyrene and south to Nubia. Scholars also argue that the kingdom was founded in 304 BC because of different use of calendars: Ptolemy crowned himself in 304 BC on the ancient Egyptian calendar,[4] but in 305 BC on the ancient Macedonian calendar; to resolve the issue, the year 305/4 was counted as the first year of Ptolemaic Kingdom in Demotic papyri.[5]

Alexandria, a Greek polis founded by Alexander the Great, became the capital city and a major center of Greek culture and trade. To gain recognition by the native Egyptian populace, the Ptolemies named themselves as pharaohs. The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions by marrying their siblings per the Osiris myth, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life. The Ptolemies were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its final conquest by Rome. Their rivalry with the neighboring Seleucid Empire of West Asia led to a series of Syrian Wars in which both powers jockeyed for control of the Levant. Hellenistic culture continued to thrive in Egypt throughout the Roman and Byzantine periods until the Muslim conquest.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Background

1.2 Establishment

1.3 Rise

1.3.1 Ptolemy I

1.3.2 Ptolemy II

1.3.3 Ptolemy III Euergetes

1.4 Decline

1.4.1 Ptolemy IV

1.4.2 Ptolemy V Epiphanes and Ptolemy VI Philometor

1.5 Later Ptolemies

1.6 Final years of the empire

1.6.1 Cleopatra

1.6.2 Roman rule

2 Culture

2.1 Art

2.2 Religion

2.3 Society

2.4 Coinage

2.5 Military

3 Cities

3.1 Naucratis

3.2 Alexandria

3.3 Ptolemais

4 Demographics

4.1 Jews

4.2 Arabs

5 Agriculture

6 List of Ptolemaic rulers

7 See also

8 Citations

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

History

The era of Ptolemaic reign in Egypt is one of the best-documented time periods of the Hellenistic period; a wealth of papyri written in Koine Greek and Egyptian have been discovered in Egypt.[6]

Background

Ptolemy as Pharaoh of Egypt, British Museum, London

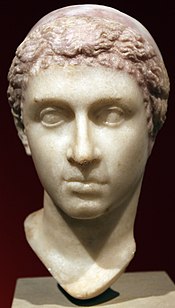

A bust depicting Pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus 309–246 BC

In 332 BC, Alexander the Great, King of Macedon, invaded Egypt, which at the time was a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire known as the Thirty-first Dynasty under Emperor Artaxerxes III.[7] He visited Memphis, and traveled to the oracle of Amun at the Siwa Oasis. The oracle declared him to be the son of Amun.

Alexander conciliated the Egyptians by the respect he showed for their religion, but he appointed Macedonians to virtually all the senior posts in the country, and founded a new Greek city, Alexandria, to be the new capital. The wealth of Egypt could now be harnessed for Alexander's conquest of the rest of the Achaemenid Empire. Early in 331 BC he was ready to depart, and led his forces away to Phoenicia. He left Cleomenes of Naucratis as the ruling nomarch to control Egypt in his absence. Alexander never returned to Egypt.

Establishment

Following Alexander's death in Babylon in 323 BC,[8] a succession crisis erupted among his generals. Initially, Perdiccas ruled the empire as regent for Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus, who became Philip III of Macedon, and then as regent for both Philip III and Alexander's infant son Alexander IV of Macedon, who had not been born at the time of his father's death. Perdiccas appointed Ptolemy, one of Alexander's closest companions, to be satrap of Egypt. Ptolemy ruled Egypt from 323 BC, nominally in the name of the joint kings Philip III and Alexander IV. However, as Alexander the Great's empire disintegrated, Ptolemy soon established himself as ruler in his own right. Ptolemy successfully defended Egypt against an invasion by Perdiccas in 321 BC, and consolidated his position in Egypt and the surrounding areas during the Wars of the Diadochi (322–301 BC). In 305 BC, Ptolemy took the title of King. As Ptolemy I Soter ("Saviour"), he founded the Ptolemaic dynasty that was to rule Egypt for nearly 300 years.

All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy, while princesses and queens preferred the names Cleopatra, Arsinoë and Berenice. Because the Ptolemaic kings adopted the Egyptian custom of marrying their sisters, many of the kings ruled jointly with their spouses, who were also of the royal house. This custom made Ptolemaic politics confusingly incestuous, and the later Ptolemies were increasingly feeble. The only Ptolemaic Queens to officially rule on their own were Berenice III and Berenice IV. Cleopatra V did co-rule, but it was with another female, Berenice IV. Cleopatra VII officially co-ruled with Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator, Ptolemy XIV, and Ptolemy XV, but effectively, she ruled Egypt alone.

The early Ptolemies did not disturb the religion or the customs of the Egyptians. They built magnificent new temples for the Egyptian gods and soon adopted the outward display of the Pharaohs of old. During the reign of Ptolemies II and III, thousands of Macedonian veterans were rewarded with grants of farm lands, and Macedonians were planted in colonies and garrisons or settled themselves in the villages throughout the country. Upper Egypt, farthest from the centre of government, was less immediately affected, even though Ptolemy I established the Greek colony of Ptolemais Hermiou to be its capital. But within a century, Greek influence had spread through the country and intermarriage had produced a large Greco-Egyptian educated class. Nevertheless, the Greeks always remained a privileged minority in Ptolemaic Egypt. They lived under Greek law, received a Greek education, were tried in Greek courts, and were citizens of Greek cities.

Rise

Ptolemy I

The first part of Ptolemy I's reign was dominated by the Wars of the Diadochi between the various successor states to the empire of Alexander. His first objective was to hold his position in Egypt securely, and secondly to increase his domain. Within a few years he had gained control of Libya, Coele-Syria (including Judea), and Cyprus. When Antigonus, ruler of Syria, tried to reunite Alexander's empire, Ptolemy joined the coalition against him. In 312 BC, allied with Seleucus, the ruler of Babylonia, he defeated Demetrius, the son of Antigonus, in the battle of Gaza.

In 311 BC, a peace was concluded between the combatants, but in 309 BC war broke out again, and Ptolemy occupied Corinth and other parts of Greece, although he lost Cyprus after a sea-battle in 306 BC. Antigonus then tried to invade Egypt but Ptolemy held the frontier against him. When the coalition was renewed against Antigonus in 302 BC, Ptolemy joined it, but neither he nor his army were present when Antigonus was defeated and killed at Ipsus. He had instead taken the opportunity to secure Coele-Syria and Palestine, in breach of the agreement assigning it to Seleucus, thereby setting the scene for the future Syrian Wars.[9] Thereafter Ptolemy tried to stay out of land wars, but he retook Cyprus in 295 BC.

Feeling the kingdom was now secure, Ptolemy shared rule with his son Ptolemy II by Queen Berenice in 285 BC. He then may have devoted his retirement to writing a history of the campaigns of Alexander—which unfortunately was lost but was a principal source for the later work of Arrian. Ptolemy I died in 283 BC at the age of 84. He left a stable and well-governed kingdom to his son.

Ptolemy II

Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who succeeded his father as King of Egypt in 283 BC,[10] was a peaceful and cultured king, and no great warrior. He did not need to be, because his father had left Egypt strong and prosperous. Three years of campaigning at the start of his reign (called the First Syrian War) left Ptolemy the master of the eastern Mediterranean, controlling the Aegean islands (the Nesiotic League) and the coastal districts of Cilicia, Pamphylia, Lycia and Caria. However, some of these territories were lost near the end of his reign as a result of the Second Syrian War. In the 270s BC, Ptolemy II defeated the Kingdom of Kush in war, gaining the Ptolemies free access to Kushite territory and control of important gold-mining areas south of Egypt known as Dodekasoinos.[11] As a result, the Ptolemies established hunting stations and ports as far south as Port Sudan, from where raiding parties containing hundreds of men searched for war elephants.[11] Hellenistic culture would acquire an important influence on Kush at this time.[11]

Ptolemy's first wife, Arsinoe I, daughter of Lysimachus, was the mother of his legitimate children. After her repudiation he followed Egyptian custom and married his sister, Arsinoe II, beginning a practice that, while pleasing to the Egyptian population, had serious consequences in later reigns. The material and literary splendour of the Alexandrian court was at its height under Ptolemy II. Callimachus, keeper of the Library of Alexandria, Theocritus and a host of other poets, glorified the Ptolemaic family. Ptolemy himself was eager to increase the library and to patronise scientific research. He spent lavishly on making Alexandria the economic, artistic and intellectual capital of the Hellenistic world. It is to the academies and libraries of Alexandria that we owe the preservation of so much Greek literary heritage.

Ptolemy III Euergetes

Coin depicting Pharaoh Ptolemy III Euergetes. Ptolemaic Kingdom.

Ptolemy III Euergetes ("the Benefactor") succeeded his father in 246 BC. He abandoned his predecessors' policy of keeping out of the wars of the other Macedonian successor kingdoms, and plunged into the Third Syrian War (246-241 BC) with the Seleucid Empire of Syria, when his sister, Queen Berenice and her son were murdered in a dynastic dispute. Ptolemy marched triumphantly into the heart of the Seleucid realm, as far as Babylonia, while his fleets in the Aegean Sea made fresh conquests as far north as Thrace.

This victory marked the zenith of the Ptolemaic power. Seleucus II Callinicus kept his throne, but Egyptian fleets controlled most of the coasts of Anatolia and Greece. After this triumph Ptolemy no longer engaged actively in war, although he supported the enemies of Macedon in Greek politics. His domestic policy differed from his father's in that he patronised the native Egyptian religion more liberally: he left larger traces among the Egyptian monuments. In this his reign marks the gradual Egyptianisation of the Ptolemies.

Decline

Ptolemaic Empire in 200 BC. Also showing neighboring powers.

Ring of Ptolemy VI Philometor as Egyptian pharaoh. Louvre Museum.

Ptolemy IV

In 221 BC, Ptolemy III died and was succeeded by his son Ptolemy IV Philopator, a weak and corrupt king under whom the decline of the Ptolemaic kingdom began. His reign was inaugurated by the murder of his mother, and he was always under the influence of royal favourites, male and female, who controlled the government. Nevertheless, his ministers were able to make serious preparations to meet the attacks of Antiochus III the Great on Coele-Syria, and the great Egyptian victory of Raphia in 217 BC secured the kingdom. A sign of the domestic weakness of his reign was the rebellions by native Egyptians that took away over half the country for over 20 years. Philopator was devoted to orgiastic religions and to literature. He married his sister Arsinoë, but was ruled by his mistress Agathoclea.

Ptolemy V Epiphanes and Ptolemy VI Philometor

A mosaic from Thmuis (Mendes), Egypt, created by the Hellenistic artist Sophilos (signature) in about 200 BC, now in the Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria, Egypt; the woman depicted is Queen Berenice II (who ruled jointly with her husband Ptolemy III Euergetes) as the personification of Alexandria, with her crown showing a ship's prow, while she sports an anchor-shaped brooch for her robes, symbols of the Ptolemaic Kingdom's naval prowess and successes in the Mediterranean Sea.[12]

Ptolemy V Epiphanes, son of Philopator and Arsinoë, was a child when he came to the throne, and a series of regents ran the kingdom. Antiochus III the Great of The Seleucid Empire and Philip V of Macedon made a compact to seize the Ptolemaic possessions. Philip seized several islands and places in Caria and Thrace, while the battle of Panium in 200 BC transferred Coele-Syria from Ptolemaic to Seleucid control. After this defeat Egypt formed an alliance with the rising power in the Mediterranean, Rome. Once he reached adulthood Epiphanes became a tyrant, before his early death in 180 BC. He was succeeded by his infant son Ptolemy VI Philometor.

In 170 BC, Antiochus IV Epiphanes invaded Egypt and deposed Philometor. In some versions of the Bible, the book of 1 Maccabees translates the passage as:

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

When Antiochus saw that his kingdom was established, he determined to become king of the land of Egypt, in order that he might reign over both kingdoms. So he invaded Egypt with a strong force, with chariots and elephants and cavalry and with a large fleet. He engaged King Ptolemy of Egypt in battle, and Ptolemy turned and fled before him, and many were wounded and fell. They captured the fortified cities in the land of Egypt, and he plundered the land of Egypt.

— 1 Maccabees 1:16–1:19

Philometor's younger brother (later Ptolemy VIII Physcon) was installed as a puppet king. When Antiochus withdrew, the brothers agreed to reign jointly with their sister Cleopatra II. They soon fell out, however, and quarrels between the two brothers allowed Rome to interfere and to steadily increase its influence in Egypt. Philometor eventually regained the throne. In 145 BC, he was killed in the Battle of Antioch.

Later Ptolemies

Philometor was succeeded by yet another infant, his son Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator. But Euergetes soon returned, killed his young nephew, seized the throne and as Ptolemy VIII soon proved himself a cruel tyrant. On his death in 116 BC he left the kingdom to his wife Cleopatra III and her son Ptolemy IX Philometor Soter II. The young king was driven out by his mother in 107 BC, who reigned jointly with Euergetes's youngest son Ptolemy X Alexander I. In 88 BC Ptolemy IX again returned to the throne, and retained it until his death in 80 BC. He was succeeded by Ptolemy XI Alexander II, the son of Ptolemy X. He was lynched by the Alexandrian mob after murdering his stepmother, who was also his cousin, aunt and wife. These sordid dynastic quarrels left Egypt so weakened that the country became a de facto protectorate of Rome, which had by now absorbed most of the Greek world.

Ptolemy XI was succeeded by a son of Ptolemy IX, Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos, nicknamed Auletes, the flute-player. By now Rome was the arbiter of Egyptian affairs, and annexed both Libya and Cyprus. In 58 BC Auletes was driven out by the Alexandrian mob, but the Romans restored him to power three years later. He died in 51 BC, leaving the kingdom to his ten-year-old son, Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator, who reigned jointly with his 17-year-old sister and wife, Cleopatra VII.

Final years of the empire

Cleopatra

Coin of Cleopatra VII, with her effigy[13]

Cleopatra VII ascended the Egyptian throne at the age of eighteen upon the death of her father, Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos. She reigned as queen "philopator" and pharaoh with various male co-regents from 51 to 30 BC when she died at the age of 39.

The demise of the Ptolemies' power coincided with the growing dominance of the Roman Republic. Having little choice, and witnessing one city after another falling to Macedon and the Seleucid empire, the Ptolemies chose to ally with the Romans, a pact that lasted over 150 years. During the rule of the later Ptolemies, Rome gained more and more power over Egypt, and was eventually declared guardian of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Cleopatra's father, Ptolemy XII, paid vast sums of Egyptian wealth and resources in tribute to the Romans in order to secure his throne. After his death, Cleopatra and her younger brother inherited the throne, but their relationship soon degenerated. Cleopatra was stripped of authority and title by Ptolemy XIII's advisors. Fleeing into exile, she would attempt to raise an army to reclaim the throne.

Ptolemy XII, father of Cleopatra VII as Pharaoh. Found at the Temple of Crocodile, Fayoum

Julius Caesar left Rome for Alexandria in 48 BC in order to quell the looming civil war, as war in Egypt, which was one of Rome's greatest suppliers of grain and other expensive goods, would have had a detrimental effect on trade. During his stay in the Alexandrian palace, he received 22-year-old Cleopatra, allegedly carried to him in secret wrapped in a carpet. She counted on Caesar's support to alienate Ptolemy XIII. With the arrival of Roman reinforcements, and after the battles in Alexandria, Ptolemy XIII was defeated at the Battle of the Nile. He later drowned in the river, although the circumstances of his death are unclear.

Relief of Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra VII and Caesarion, Dendera Temple, Egypt.

In the summer of 47 BC, having married her younger brother Ptolemy XIV, Cleopatra embarked with Caesar for a two-month trip along the Nile. Together, they visited Dendara, where Cleopatra was being worshiped as pharaoh, an honor beyond Caesar's reach. They became lovers, and she bore him a son, Caesarion. In 45 BC, Cleopatra and Caesarion left Alexandria for Rome, where they stayed in a palace built by Caesar in their honor.

In 44 BC, Caesar was murdered in Rome by several Senators. With his death, Rome split between supporters of Mark Antony and Octavian. When Mark Antony seemed to prevail, Cleopatra supported him and, shortly after, they too became lovers and eventually married in Egypt (though their marriage was never recognized by Roman law, as Antony was married to a Roman woman). Their union produced three children; the twins Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios, and another son, Ptolemy Philadelphos.

Mark Antony's alliance with Cleopatra angered Rome even more. Branded a power-hungry enchantress by the Romans, she was accused of seducing Antony to further her conquest of Rome. Further outrage followed at the donations of Alexandria ceremony in autumn of 34 BC in which Tarsus, Cyrene, Crete, Cyprus, and Israel were all to be given as client monarchies to Antony's children by Cleopatra. In his will Antony expressed his desire to be buried in Alexandria, rather than taken to Rome in the event of his death, which Octavian used against Antony, sowing further dissent in the Roman populace.

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinnerwidth:100%!important;max-width:none!important.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsinglefloat:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center

Right: bust of Cleopatra VII, dated 40–30 BC, Vatican Museums, showing her with a 'melon' hairstyle and Hellenistic royal diadem worn over her head

Octavian was quick to declare war on Antony and Cleopatra while public opinion of Antony was low. Their naval forces met at Actium, where the forces of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa defeated the navy of Cleopatra and Antony. Octavian waited for a year before he claimed Egypt as a Roman province. He arrived in Alexandria and easily defeated Mark Antony's remaining forces outside the city. Facing certain death at the hands of Octavian, Antony attempted suicide by falling on his own sword. He survived briefly, however, and was taken to Cleopatra, who had barricaded herself in her mausoleum, where he died soon after.

Knowing that she would be taken to Rome to be paraded in Octavian's triumph (and likely executed thereafter), Cleopatra and her handmaidens committed suicide on 12 August 30 BC. Legend and numerous ancient sources claim that she died by way of the venomous bite of an asp, though others state that she used poison, or that Octavian ordered her death himself.

Caesarion, her son by Julius Caesar, nominally succeeded Cleopatra until his capture and supposed execution in the weeks after his mother's death. Cleopatra's children by Antony were spared by Octavian and given to his sister (and Antony's Roman wife) Octavia Minor, to be raised in her household. Their daughter Cleopatra Selene was eventually married through arrangement by Octavian into the Mauretanian royal line. Through her offspring the Ptolemaic line intermarried back into the Roman nobility.

With the deaths of Cleopatra and Caesarion, the dynasty of Ptolemies and the entirety of pharaonic Egypt came to an end. Alexandria remained the capital of the country, but Egypt itself became a Roman province. Octavian became the sole ruler of Rome and began converting it into a monarchy, the Roman Empire.

Roman rule

Bust of Roman Nobleman, c. 30 BC – 50 AD, 54.51, Brooklyn Museum

Under Roman rule, Egypt was governed by a prefect selected by the emperor from the Equestrian class and not a governor from the Senatorial order, to prevent interference by the Roman Senate. The main Roman interest in Egypt was always the reliable delivery of grain to the city of Rome. To this end the Roman administration made no change to the Ptolemaic system of government, although Romans replaced Greeks in the highest offices. But Greeks continued to staff most of the administrative offices and Greek remained the language of government except at the highest levels. Unlike the Greeks, the Romans did not settle in Egypt in large numbers. Culture, education and civic life largely remained Greek throughout the Roman period. The Romans, like the Ptolemies, respected and protected Egyptian religion and customs, although the cult of the Roman state and of the Emperor was gradually introduced.[citation needed]

Around 25 BC, the Greek geographer, philosopher and historian, Strabo sailed up the Nile until reaching Philae, after which point there is little record of his proceedings until AD 17.[14]

According to a 2017 study in Nature Communications, volcanic eruptions impacted the Nile in a way as to adversely impact agricultural output and thus trigger revolt in Ptolemaic Egypt.[15]

Culture

Ptolemaic mosaic of a dog and askos wine vessel from Hellenistic Egypt, dated 200-150 BC, Greco-Roman Museum of Alexandria, Egypt

Ptolemy I, perhaps with advice from Demetrius of Phalerum, founded the Museum and Library of Alexandria.[16] The Museum was a research centre supported by the king. It was located in the royal sector of the city. The scholars were housed in the same sector and funded by the Ptolemaic rulers.[16] The chief librarian served also as the crown prince's tutor.[17] For the first hundred and fifty years of its existence this library and research centre drew the top Greek scholars.[17] It was a key academic, literary and scientific centre.[18]

Greek culture had a long but minor presence in Egypt long before Alexander the Great founded the city of Alexandria. It began when Greek colonists, encouraged by the many Pharaohs, set up the trading post of Naucratis. As Egypt came under foreign domination and decline, the Pharaohs depended on the Greeks as mercenaries and even advisors. When the Persians took over Egypt, Naucratis remained an important Greek port and the colonist population were used as mercenaries by both the rebel Egyptian princes and the Persian kings, who later gave them land grants, spreading Greek culture into the valley of the Nile. When Alexander the Great arrived, he established Alexandria on the site of the Persian fort of Rhakortis. Following Alexander's death, control passed into the hands of the Lagid (Ptolemaic) Dynasty; they built Greek cities across their empire and gave land grants across Egypt to the veterans of their many military conflicts. Hellenistic civilization continued to thrive even after Rome annexed Egypt after the battle of Actium and did not decline until the Islamic conquests.

Faience sistrum with head of Hathor with bovine ears from the reign of Ptolemy I.[19] Color is intermediate between traditional Egyptian color to colors more characteristic of Ptolemaic-era faience.[20]

Art

Ptolemaic art was produced during the reign of the Ptolemaic Rulers (304–30 BC), and was concentrated primarily within the bounds of the Ptolemaic Empire.[21][22] At first, artworks existed separately in either the Egyptian or the Hellenistic style, and over time, these characteristics began to combine. The continuation of Egyptian art style evidences the Ptolemies' commitment to maintaining Egyptian customs. This strategy not only helped to legitimize their rule, but also placated the general population.[23] Greek-style art was also created during this time and existed in parallel to the more traditional Egyptian art, which could not largely be altered without changing its intrinsic, primarily-religious function.[24] Art found outside of Egypt itself, though within the Ptolemaic Kingdom, sometimes used Egyptian iconography as it had been used previously, and sometimes adapted it.[25][26]

For example, the faience sistrum inscribed with the name of Ptolemy has some deceptively Greek characteristics, such as the scrolls at the top, however, there are many examples of nearly identical sistrum and columns dating all the way to Dynasty 18 in the New Kingdom. It is, therefore, purely Egyptian in style. Aside from the name of the king, there are other features that specifically date this to the Ptolemaic period. Most distinctively is the color of the faience. Apple green, deep blue, and lavender-blue are the three colors most frequently used during this period, a shift from the characteristic blue of the earlier kingdoms.[19] This sistrum appears to be an intermediate hue, which fits with its date at the beginning of the Ptolemaic empire.

During the reign of Ptolemy II, Arsinoe II was deified either as stand-alone goddesses or as a personification of another divine figure and given their own sanctuaries and festivals in association to both Egyptian and Hellenistic gods (such as Isis of Egypt and Hera of Greece).[27] For example, Head Attributed to Arsinoe II deified her as an Egyptian goddess. However, the Marble head of a Ptolemaic queen deified Arsinoe II as Hera.[27] Coins from this period also show Arsinoe II with a diadem that is solely worn by goddesses and deified royal women.[28]

Relief from the temple of Kom Ombo depicting Ptolemy VIII receiving the sed symbol from Horus.[29]

The Statuette of Arsinoe II was created c. 150–100 BC, well after her death, as a part of her own specific posthumous cult which was started by her husband Ptolemy II. The figure also exemplifies the fusing of Greek and Egyptian art. Although the backpillar and the goddess’s striding pose is distinctively Egyptian, the cornucopia she holds and her hairstyle are both Greek in style. The rounded eyes, prominent lips, and overall youthful features show Greek influence as well.[30]

Temple of Kom Ombo constructed in Upper Egypt in 180–47 BC by the Ptolemies and modified by the Romans. It is a double temple with two sets of structures dedicated to two separate deities.

Despite the unification of Greek and Egyptian elements in the intermediate Ptolemaic period, the Ptolemaic Kingdom also featured prominent temple construction as a continuation of developments based on Egyptian art tradition from the Thirtieth Dynasty.[31][32] Such behavior expanded the rulers' social and political capital and demonstrated their loyalty toward Egyptian deities, to the satisfaction of the local people.[33] Temples remained very New Kingdom and Late Period Egyptian in style though resources were oftentimes provided by foreign powers.[31] Temples were models of the cosmic world with basic plans retaining the pylon, open court, hypostyle halls, and dark and centrally located sanctuary.[31] However, ways of presenting text on columns and reliefs became formal and rigid during the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Scenes were often framed with textual inscriptions, with a higher text to image ratio than seen previously during the New Kingdom.[31] For example, a relief the temple of Kom Ombo is separated from other scenes by two vertical columns of texts. The figures in the scenes are smooth, rounded, and high relief, a style continued throughout the 30th Dynasty. The relief represents the interaction between the Ptolemaic kings and the Egyptian deities, which legitimized their rule in Egypt .[29]

In Ptolemaic art, the idealism seen in the art of previous dynasties continues, with some alterations. Women are portrayed as more youthful, and men begin to be portrayed in a range from idealistic to realistic.[18][25] An example of realistic portrayal is the Berlin Green Head, which shows the non-idealistic facial features with vertical lines above the bridge of the nose, lines at the corners of the eyes and between the nose and the mouth.[26] The influence of Greek art was shown in an emphasis on the face that was not previously present in Egyptian art and incorporation of Greek elements into an Egyptian setting: individualistic hairstyles, the oval face, “round [and] deeply set” eyes, and the small, tucked mouth closer to the nose.[27] Early portraits of the Ptolemies featured large and radiant eyes in association to the rulers’ divinity as well as general notions of abundance.[34]

Gold coin with visage of Arsinoe II wearing divine diadem

Bronze allegorical group of a Ptolemy (identifiable by his diadem) overcoming an adversary, in Hellenistic style, ca early 2nd century BC (Walters Art Museum)

Religion

When Ptolemy I Soter made himself king of Egypt, he created a new god, Serapis, which was a combination of two Egyptian gods: Apis and Osiris, plus the main Greek gods: Zeus, Hades, Asklepios, Dionysos, and Helios. Serapis had powers over fertility, the sun, corn, funerary rites, and medicine. Many people started to worship this god. In the time of the Ptolemies, the cult of Serapis included the worship of the new Ptolemaic line of pharaohs. Alexandria supplanted Memphis as the preeminent religious city. Ptolemy I also promoted the cult of the deified Alexander, who became the state god of the Ptolemaic kingdom; the Ptolemies eventually associated themselves with the cult as gods.

The wife of Ptolemy II, Arsinoe II, was often depicted in the form of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, but she wore the crown of lower Egypt, with ram's horns, ostrich feathers, and other traditional Egyptian indicators of royalty and/or deification. She wore the vulture headdress only on the religious portion of a relief. Cleopatra VII, the last of the Ptolemaic line, was often depicted with characteristics of the goddess Isis. She often had either a small throne as her headdress or the more traditional sun disk between two horns.[35]

The traditional table for offerings disappeared from reliefs during the Ptolemaic period. Male gods were no longer portrayed with tails in attempt to make them more human-like.

A common stele that appears during the Ptolemaic Dynasty is the cippus, religious objects produced for the purpose of protection of individuals. These magical stelae were made of various materials such as limestone, chlorite schist, and meta-grey-wacke, and were connected with matters of health. Cippi during the Ptolemaic Period featured the child form of the Egyptian god Horus (Horpakhered). This portrayal of Horus refers to the myth wherein Horus triumphs over dangerous animals in the marshes of Khemmis with magic power (also known as Akhmim).[36][37] Thus, people would keep the Cippus for protection purpose.

Society

The Greeks now formed the new upper classes in Egypt, replacing the old native aristocracy. In general, the Ptolemies undertook changes that went far beyond any other measures that earlier foreign rulers had imposed. They used the religion and traditions to increase their own power and wealth. Although they established a prosperous kingdom, enhanced with fine buildings, the native population enjoyed few benefits, and there were frequent uprisings. These expressions of nationalism reached a peak in the reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator (221–205 BC) when others gained control over one district and ruled as a line of native "pharaohs." This was only curtailed nineteen years later when Ptolemy V Epiphanes (205–181 BC) succeeded in subduing them, but the underlying grievances continued and there were riots again later in the dynasty.

Family conflicts affected the later years of the dynasty when Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II fought his brother Ptolemy VI Philometor and briefly seized the throne. The struggle was continued by his sister and niece (who both became his wives) until they finally issued an Amnesty Decree in 118 BC.

Example of a large Ptolemaic bronze coin minted during the reign of Ptolemy V.

Coinage

Ptolemaic Egypt was noted for its extensive series of coinage in gold, silver and bronze. It was especially noted for its issues of large coins in all three metals, most notably gold pentadrachm and octadrachm, and silver tetradrachm, decadrachm and pentakaidecadrachm. This was especially noteworthy as it would not be until the introduction of the Guldengroschen in 1486 that coins of substantial size (particularly in silver) would be minted in significant quantities[citation needed].

Military

Hellenistic soldiers in tunic, 100 BC, detail of the Nile mosaic of Palestrina.

Ptolemaic Egypt, along with the other Hellenistic states outside of the Greek mainland after Alexander the Great, had its armies based on the Macedonian phalanx and featured Macedonian and native troops fighting side by side.

The Ptolemaic military was filled with diverse peoples from across their territories. At first most of the military was made up of a pool of Greek settlers who, in exchange for military service, were given land grants. These made up the majority of the army.

With the many wars the Ptolemies were involved in, their pool of Macedonian troops dwindled and there was little Greek immigration from the mainland so they were kept in the royal bodyguard and as generals and officers. Native troops were looked down upon and distrusted due to their disloyalty and frequent tendency to aid local revolts. However, with the decline of royal power, they gained influence and became common in the military.

The Ptolemies used the great wealth of Egypt to their advantage by hiring vast amounts of mercenaries from across the known world. Black Ethiopians are also known to have served in the military along with the Galatians, Mysians and others.

With their vast amount of territory spread along the Eastern Mediterranean such as Cyprus, Crete, the islands of the Aegean and even Thrace, the Ptolemies required a large navy to defend these far-flung strongholds from enemies like the Seleucids and Macedonians.

Cities

Egyptian faience torso of a king, for an applique on wood

While ruling Egypt, the Ptolemaic Dynasty built many Greek settlements throughout their Empire, to either Hellenize new conquered peoples or reinforce the area. Egypt had only three main Greek cities—Alexandria, Naucratis, and Ptolemais.

Naucratis

Of the three Greek cities, Naucratis, although its commercial importance was reduced with the founding of Alexandria, continued in a quiet way its life as a Greek city-state. During the interval between the death of Alexander and Ptolemy's assumption of the style of king, it even issued an autonomous coinage. And the number of Greek men of letters during the Ptolemaic and Roman period, who were citizens of Naucratis, proves that in the sphere of Hellenic culture Naucratis held to its traditions. Ptolemy II bestowed his care upon Naucratis. He built a large structure of limestone, about 100 metres (330 ft) long and 18 metres (59 ft) wide, to fill up the broken entrance to the great Temenos; he strengthened the great block of chambers in the Temenos, and re-established them. At the time when Sir Flinders Petrie wrote the words just quoted[citation needed] the great Temenos was identified with the Hellenion. But Mr. Edgar has recently pointed out that the building connected with it was an Egyptian temple, not a Greek building.[citation needed] Naucratis, therefore, in spite of its general Hellenic character, had an Egyptian element. That the city flourished in Ptolemaic times "we may see by the quantity of imported amphorae, of which the handles stamped at Rhodes and elsewhere are found so abundantly." The Zeno papyri show that it was the chief port of call on the inland voyage from Memphis to Alexandria, as well as a stopping-place on the land-route from Pelusium to the capital. It was attached, in the administrative system, to the Saïte nome.

Alexandria

Alexander the Great, 356 –323 BC Brooklyn Museum

A major Mediterranean port of Egypt, in ancient times and still today, Alexandria was founded in 331 BC by Alexander the Great. According to Plutarch, the Alexandrians believed that Alexander the Great's motivation to build the city was his wish to "found a large and populous Greek city that should bear his name." Located 30 kilometres (19 mi) west of the Nile's westernmost mouth, the city was immune to the silt deposits that persistently choked harbors along the river. Alexandria became the capital of the Hellenized Egypt of King Ptolemy I (reigned 323–283 BC). Under the wealthy Ptolemaic Dynasty, the city soon surpassed Athens as the cultural center of the Hellenic world.

Laid out on a grid pattern, Alexandria occupied a stretch of land between the sea to the north and Lake Mareotis to the south; a man-made causeway, over three-quarters of a mile long, extended north to the sheltering island of Pharos, thus forming a double harbor, east and west. On the east was the main harbor, called the Great Harbor; it faced the city's chief buildings, including the royal palace and the famous Library and Museum. At the Great Harbor's mouth, on an outcropping of Pharos, stood the lighthouse, built c. 280 BC. Now vanished, the lighthouse was reckoned as one of the Seven Wonders of the World for its unsurpassed height (perhaps 140 metres or 460 ft); it was a square, fenestrated tower, topped with a metal fire basket and a statue of Zeus the Savior.

The Library, at that time the largest in the world, contained several hundred thousand volumes and housed and employed scholars and poets. A similar scholarly complex was the Museum (Mouseion, "hall of the Muses"). During Alexandria's brief literary golden period, c. 280–240 BC, the Library subsidized three poets—Callimachus, Apollonius of Rhodes

, and Theocritus—whose work now represents the best of Hellenistic literature. Among other thinkers associated with the Library or other Alexandrian patronage were the mathematician Euclid (c. 300 BC), the inventor Archimedes (287 BC – c. 212 BC), and the polymath Eratosthenes (c. 225 BC).[38]

Cosmopolitan and flourishing, Alexandria possessed a varied population of Greeks, Egyptians and other Oriental peoples, including a sizable minority of Jews, who had their own city quarter. Periodic conflicts occurred between Jews and ethnic Greeks. According to

Strabo, Alexandria had been inhabited during Polybius' lifetime by local Egyptians, foreign mercenaries and the tribe of the Alexandrians, whose origin and customs Polybius identified as Greek.

The city enjoyed a calm political history under the Ptolemies. It passed, with the rest of Egypt, into Roman hands in 30 BC, and became the second city of the Roman Empire.

A detail of the Nile mosaic of Palestrina, showing Ptolemaic Egypt c. 100 BC

Ptolemais

The second Greek city founded after the conquest of Egypt was Ptolemais, 400 miles (640 km) up the Nile, where there was a native village called Psoï, in the nome called after the ancient Egyptian city of Thinis. If Alexandria perpetuated the name and cult of the great Alexander, Ptolemais was to perpetuate the name and cult of the founder of the Ptolemaic time. Framed in by the barren hills of the Nile Valley and the Egyptian sky, here a Greek city arose, with its public buildings and temples and theatre, no doubt exhibiting the regular architectural forms associated with Greek culture, with a citizen-body Greek in blood, and the institutions of a Greek city. If there is some doubt whether Alexandria possessed a council and assembly, there is none in regard to Ptolemais. It was more possible for the kings to allow a measure of self-government to a people removed at that distance from the ordinary residence of the court. We have still, inscribed on stone, decrees passed in the assembly of the people of Ptolemais, couched in the regular forms of Greek political tradition: It seemed good to the boule and to the demos: Hermas son of Doreon, of the deme Megisteus, was the proposer: Whereas the prytaneis who were colleagues with Dionysius the son of Musaeus in the 8th year, etc.

Demographics

A stele of Dioskourides, dated 2nd century BC, showing a Ptolemaic thureophoros soldier. It is a characteristic example of the "Romanization" of the Ptolemaic army.

The Ptolemaic kingdom was diverse in the people who settled and made Egypt their home at this time. During this period, Macedonian troops under Ptolemy I Soter were given land grants and brought their families encouraging tens of thousands of Greeks to settle the country making themselves the new ruling class. Native Egyptians continued having a role, albeit a small one, in the Ptolemaic government, mostly in lower posts, and outnumbered the foreigners. During the reign of the Ptolemaic Pharaohs, many Jews were imported from neighboring Judea by the thousands for being renowned fighters and established an important presence there. Other foreign groups settled, and even Galatian mercenaries were invited. Of the aliens who had come to settle in Egypt, the ruling group, the Greeks, were the most important element. They were partly spread as allotment-holders over the country, forming social groups, in the country towns and villages, side by side with the native population, partly gathered in the three Greek cities, the old Naucratis, founded before 600 BC (in the interval of Egyptian independence after the expulsion of the Assyrians and before the coming of the Persians), and the two new cities, Alexandria by the sea, and Ptolemais in Upper Egypt. Alexander and his Seleucid successors founded many Greek cities all over their dominions.

Greek culture was so much bound up with the life of the city-state that any king who wanted to present himself to the world as a genuine champion of Hellenism had to do something in this direction, but the king of Egypt, ambitious to shine as a Hellene, would find Greek cities, with their republican tradition and aspirations to independence, inconvenient elements in a country that lent itself, as no other did, to bureaucratic centralization. The Ptolemies therefore limited the number of Greek city-states in Egypt to Alexandria, Ptolemais, and Naucratis.

Outside of Egypt, they had Greek cities under their dominion, including the old Greek cities in the Cyrenaica, in Cyprus, on the coasts and islands of the Aegean, but they were smaller than the three big ones in Egypt. There were indeed country towns with names such as Ptolemais, Arsinoe, and Berenice, in which Greek communities existed with a certain social life and there were similar groups of Greeks in many of the old Egyptian towns, but they were not communities with the political forms of a city-state. Yet if they had no place of political assembly, they would have their gymnasium, the essential sign of Hellenism, serving something of the purpose of a university for the young men. Far up the Nile at Ombi a gymnasium of the local Greeks was found in 136–135 BC, which passed resolutions and corresponded with the king. Also, in 123 BC, when there was trouble in Upper Egypt between the towns of Crocodilopolis and Hermonthis, the negotiators sent from Crocodilopolis were the young men attached to the gymnasium, who, according to the Greek tradition, ate bread and salt with the negotiators from the other town. All the Greek dialects of the Greek world gradually became assimilated in the Koine Greek dialect that was the common language of the Hellenistic world. Generally, the Greeks of Ptolemaic Egypt felt like representatives of a higher civilization but were curious about the native culture of Egypt.

Ptolemaic Era bust of a man, circa 300-250 BC, Altes Museum

Jews

The Jews who lived in Egypt had originally immigrated from the Southern Levant. The Jews absorbed Greek, the dominant language of Egypt at the time, and heavily mixed it with Hebrew.[39] The Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures, appeared and was written by seventy Jewish Translators under royal compulsion during Ptolemy II's reign.[40] That is confirmed by historian Flavius Josephus, who writes that Ptolemy, desirous to collect every book in the habitable earth, applied Demetrius Phalereus to the task of organizing an effort with the Jewish high priests to translate the Jewish books of the Law for his library.[41] Josephus thus places the origins of the Septuagint in the 3rd century BC, when Demetrius and Ptolemy II lived. According to Jewish legend, the seventy wrote their translations independently from memory, and the resultant works were identical at every letter.

Arabs

In 1990, more than 2,000 papyri written by Zeno of Caunus from the time of Ptolemy II Philadelphus were discovered, which contained at least 19 references to Arabs in the area between the Nile and the Red Sea, and mentioned their jobs as police officers in charge of "ten person units", and some others were mentioned as shepherds.[42]Arabs in the Ptolemaic kingdom had provided camel convoys to the armies of some Ptolemaic leaders during their invasions, but they had allegiance to none of the kingdoms of Egypt or Syria, and they managed to raid and attack both sides of the conflict between the Ptolemaic Kingdom and its enemies.[43][44]

Agriculture

The early Ptolemies increased cultivatable land through irrigation and introduced crops such as cotton and better wine-producing grapes.

List of Ptolemaic rulers

See also

- Antipatrid dynasty

- Antigonid dynasty

- Cup of the Ptolemies

- Dryton and Apollonia Archive

- Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

- Hellenistic period

- History of Egypt

- Kingdom of Pontus

- Indo-Greeks

- Library of Alexandria

- Lighthouse of Alexandria

- Seleucid Empire

Citations

^ Buraselis, Stefanou and Thompson ed; The Ptolemies, the Sea and the Nile: Studies in Waterborne Power.

^ North Africa in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods, 323 BC to AD 305, R.C.C. Law, The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 2 ed. J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver, (Cambridge University Press, 1979), 154.

^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, 18.21.9

^ Robins, Gay (2008). The Art of Ancient Egypt (Revised Edition). United States: Harvard University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-674-03065-7..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Hölbl, Günther (2001). A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. UK, USA, Canada: Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-415-23489-4.

^ Lewis, Naphtali (1986). Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt: Case Studies in the Social History of the Hellenistic World. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 5.

ISBN 0-19-814867-4.

^ Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.)". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/acha/hd_acha.htm (October 2004) Source: The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.) | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

^ Hemingway, Colette, and Seán Hemingway. "The Rise of Macedonia and the Conquests of Alexander the Great". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/alex/hd_alex.htm (October 2004)

Source: The Rise of Macedonia and the Conquests of Alexander the Great | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

^ Grabbe, L. L. (2008). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. Volume 2 – The Coming of the Greeks: The Early Hellenistic Period (335 – 175 BC). T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-03396-3.

^ Ptolemy II Philadelphus [308-246 BC. Mahlon H. Smith. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

^ abc Burstein (2007), p. 7

^ Fletcher 2008, pp. 246–247, image plates and captions

^ Cleopatra: A Life

^ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/strabo/17a3*.html

^ Manning, Joseph G.; Ludlow, Francis; Stine, Alexander R.; Boos, William R.; Sigl, Michael; Marlon, Jennifer R. (2017-10-17). "Volcanic suppression of Nile summer flooding triggers revolt and constrains interstate conflict in ancient Egypt". Nature Communications. 8 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00957-y. ISSN 2041-1723.

^ ab Peters (1970), p. 193

^ ab Peters (1970), p. 194

^ Peters (1970), p. 195f

^ ab Thomas, Ross. "Ptolemaic and Roman Faience Vessels" (PDF). The British Museum. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

^ Thomas, Ross. "Ptolemaic and Roman Faience Vessels" (PDF). The British Museum. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

^ Gay., Robins, (2008). The art of ancient Egypt (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 10, 231. ISBN 9780674030657. OCLC 191732570.

^ Lloyd, Alan (2003). Shaw, Ian, ed. The Ptolemaic Period (332-30 BC). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7.

^ Manning, J.G. (2010). The Historical Understanding of the Ptolemaic State. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 34–35.

^ Malek, Jaromir (1999). Egyptian Art. London: Phaidon Press Limited. p. 384.

^ "Bronze statuette of Horus | Egyptian, Ptolemaic | Hellenistic | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

^ "Faience amulet of Mut with double crown | Egyptian, Ptolemaic | Hellenistic | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

^ ab "Marble head of a Ptolemaic queen | Greek | Hellenistic | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

^ Pomeroy, Sarah (1990). Women in Hellenistic Egypt: From Alexander to Cleopatra. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 29.

^ ab Gay., Robins, (2008). The art of ancient Egypt (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 236. ISBN 9780674030657. OCLC 191732570.

^ "Statuette of Arsinoe II for her Posthumous Cult | Ptolemaic Period | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

^ abcd Gay., Robins, (2008). The art of ancient Egypt (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674030656. OCLC 191732570.

^ Rosalie, David (1993). Discovering Ancient Egyptology. p. 99.

^ Fischer-Bovet, Christelle. "Army and Egyptian Temple Building Under the Ptolemies" (PDF).

^ 1941-, Török, László, (2011). Hellenizing art in ancient Nubia, 300 BC-AD 250, and its Egyptian models : a study in "acculturation". Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004211284. OCLC 744946342.

^ Antiquities Experts. "Egyptian Art During the Ptolemaic Period of Egyptian History". Antiquities Experts. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

^ Gay., Robins, (2008). The art of ancient Egypt (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 244. ISBN 9780674030657. OCLC 191732570.

^ Seele, Keith C. (1947). "Horus on the Crocodiles". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 6 (1): 43–52. JSTOR 542233.

^ Phillips, Heather A., "The Great Library of Alexandria?". Library Philosophy and Practice, August 2010

^ Solomon Grayzel "A History of the Jews" p. 56

^ Solomon Grayzel "A History of the Jews" pp. 56-57

^ Flavius Josephus "Antiquities of the Jews" Book 12 Ch. 2

^ Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads, Prof. Jan Retso, Page: 301

^ A History of the Arabs in the Sudan: The inhabitants of the northern Sudan before the time of the Islamic invasions. The progress of the Arab tribes through Egypt. The Arab tribes of the Sudan at the present day, Sir Harold Alfred MacMichael, Cambridge University Press, 1922, Page: 7

^ History of Egypt, Sir John Pentland Mahaffy, p. 20-21

References

Burstein, Stanley Meyer (December 1, 2007). The Reign of Cleopatra. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806138718. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

Fletcher, Joann (2008), Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend, New York: Harper, ISBN 978-0-06-058558-7.

Peters, F. E. (1970). The Harvest of Hellenism. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

- Bingen, Jean. Hellenistic Egypt. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007 (hardcover,

ISBN 0-7486-1578-4; paperback,

ISBN 0-7486-1579-2). Hellenistic Egypt: Monarchy, Society, Economy, Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007 (hardcover,

ISBN 0-520-25141-5; paperback,

ISBN 0-520-25142-3). - Bowman, Alan Keir. 1996. Egypt After the Pharaohs: 332 BC–AD 642; From Alexander to the Arab Conquest. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Chauveau, Michel. 2000. Egypt in the Age of Cleopatra: History and Society under the Ptolemies. Translated by David Lorton. Ithaca: Cornell University Press

- Ellis, Simon P. 1992. Graeco-Roman Egypt. Shire Egyptology 17, ser. ed. Barbara G. Adams. Aylesbury: Shire Publications, ltd.

- Hölbl, Günther. 2001. A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. Translated by Tina Saavedra. London: Routledge Ltd.

- Lloyd, Alan Brian. 2000. "The Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BC)". In The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, edited by Ian Shaw. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 395–421

- Susan Stephens, Seeing Double. Intercultural Poetics in Ptolemaic Alexandria (Berkeley, 2002).

- A. Lampela, Rome and the Ptolemies of Egypt. The development of their political relations 273-80 B.C. (Helsinki, 1998).

- J. G. Manning, The Last Pharaohs: Egypt Under the Ptolemies, 305-30 BC (Princeton, 2009).

External links

Library resources about Ptolemaic Kingdom |

|

- Map of Ptolemaic Egypt, circa 270 BC