Alice Freeman Palmer

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP | Alice Elvira Freeman Palmer | |

|---|---|

Alice Freeman Palmer, 1881-1887, Wellesley College | |

| Born | (1855-02-21)February 21, 1855 Colesville, New York |

| Died | December 6, 1902(1902-12-06) (aged 47) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Houghton Chapel, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA |

| Education |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) | George Herbert Palmer (d. 1933) |

| Parent(s) | James and Elizabeth Freeman |

Alice Freeman Palmer (February 21, 1855 – December 6, 1902) was an American educator. As Alice Freeman, she was President of Wellesley College from 1881 to 1887, when she left to marry the Harvard professor George Herbert Palmer. From 1892 to 1895 she was Dean of Women at the newly founded University of Chicago.

She was an advocate for college education for women, improving their opportunities to attend college through improved college preparation, sponsorship, public lectures, and in her role in many education organizations. She was co-founder and president of the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, which later became the American Association of University Women. She was inducted into the Hall of Fame for Great Americans.

She called for women to attain a college education so that if they needed to support themselves, they would have the necessary skills to do so. An independent and effective person, unique for her time, was the model New Woman of the 19th century.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Education

3 Career

3.1 Early years

3.2 Wellesley College

3.3 Public speaker and advocate

3.4 University of Chicago

4 Personal life

5 Death

6 Posthumous honors

7 References

8 Sources

9 Further reading

10 External links

Early life

Alice Elvira Freeman was born in Colesville, New York, was the eldest child of four children of Elizabeth Josephine Higley and James Warren Freeman. From her father, she acquired her "moral beauty", as well as her height and red highlights in her hair.[1][2] Palmer was particularly close to her mother during her childhood, partly because her mother was only 17 years-of-age when she was born, and also because of their shared responsibility caring for her younger siblings and performing household duties. Elizabeth was an advocate for children and women's rights and health care, as well as the temperance movement.[3] Her father, a farmer in her early years,[4] was interested in making direct changes to people's lives, rather than through reform movements, and shared his interest in education and the sciences with his daughter.[3]

Charles Wilson Knapp, View in the Susquehanna Valley

Both of her parents came from early settlers and major landholders of the Susquehanna Valley in southern New York.[1][2] They had interests in farming and lumber.[5]

Alice Freeman Palmer, age five, about 1860

As the age of three, she taught herself to read and developed what became a lifelong enjoyment of reading aloud.[6] Her father enrolled in Albany Medical School in 1861 and graduated in 1864, which created an added burden on her mother to manage the farm when her father was away.[7] During that time she attended a rural district school.[8] After his return, when she was six-years old, the family moved into a rented house in Windsor, New York[9] and her father established a medical practice in the town. When she was ten, she began attending the co-educational Windsor Academy in her hometown.[8]

She met Thomas Barclay, a student at Yale University, in her hometown when he worked as a teacher to pay off his college expenses. He encouraged her intellectual curiosity and served as her mentor. They became close and were engaged when she was 14 years of age, but she broke off the engagement in February 1871.[10]

She was described as "an eager, ambitious student, determined by the very forces of her nature towards the getting of knowledge and the building of a symmetrical character."[4] Palmer won awards for her compositions and performance at regional oratorical contents. She was inspired by a lecture given by Anna Elizabeth Dickinson and engaged in community service, giving away some of her savings for college, at a time when she did not have a winter coat. She became a member of the Presbyterian Church in her final year at the academy, both because it was an expected action and as an expression of her personal commitment.[11]

Biographer Ruth Birgitta Anderson Bordin suggests that Palmer was influenced to gain a college education due to her relationship with Barclay, having been inspired by orator Anna Dickinson, and having experienced the financial uncertainty of her family. Palmer later said that attainment of a college education is "life insurance for a girl", should she need to provide for herself financially.[12] Her parents did not have the financial capacity to send more than one child, a son, to college. Therefore, they agree to help with the financing with the stipulation that Palmer provide financial support so that her brother and perhaps other siblings could go to college.[2][13]

Education

Alice Freeman Palmer, 1876, while at University of Michigan

In 1870, the University of Michigan began enrolling women.[2] Palmer took an entrance examination in 1872 at the University of Michigan, at the time was the largest university in the country, and had been found to have deficiency in some areas.[14] She made a strong impression on James B. Angell, the president and registrar of the university.[13] She was admitted under the condition that she make up the missing course content, which she did before her sophomore year.[15][16]

James invested in a speculative mining endeavor in 1873 and due to its failure, he lost his farm and possessions.[5] and asked for Palmer to return home. Instead, with the help of her professors, she acquired a Greek and Latin language teaching position at Ottawa, Illinois. Under the arrangement, she was allowed to continue her studies as a member of the Junior class. In addition to supporting, she was self-supporting from that point further.[8][15]

Palmer became the first of her class and was a member of the Students' Christian Association. She spoke at her commencement in 1876 about The Conflict Between Science and Poetry.[4]

Career

Early years

After she graduated from the University of Michigan, she taught at a private boarding school in Wisconsin[2] in Geneva for one school year.[15] Beginning in 1877, she was the principal of the high school at East Saginaw, Michigan. Her father declared bankruptcy in 1877[17] and Alice assumed his debts and moved the family to Saginaw to a rented house that was paid for with her principal's salary and the income that her mother made from boarders. Her father established a practice that ultimately became successful in the city. She began to suffer poor health, in part due to how hard she had worked since she was 19 years of age.[18]

Wellesley College

Evelyn Beatrice Longman, Bust of Alice Freeman Palmer, 1920, Hall of Fame for Great Americans

Henry Fowle Durant, the founder of Wellesley College, made Palmer three offers to teach at the college, first in mathematics, and then Greek.[2] Due to her sister's dire health condition, she did not accept these offers.[15] She accepted the third professorship offer to teach history in 1879.[2][19] Later that same year, her younger sister Estelle became ill and died.[2]

In October 1881, she was named acting president of Wellesley.[19] When Durant died, Palmer, at 26 years old, was elected president of the college. She was the first woman to be the head of a nationally known college. Palmer improved the academic program at Wellesley.[2][19] Palmer "transformed the fledgling school from one devoted to Christian domesticity into one of the nation's premier colleges for women."[20] She improved the academic curriculum, raised the standards for admission to the school, established 15 "feeder schools" for pre-college preparation, and recruited distinguished faculty members. She improved the image of the educated woman, against the prevailing opinion that education would affect a woman's femininity or health.[20]

The "cottage system" that she implemented brought faculty and students together in small homes.[20] She was personally engaging with students and staff and the people that were the closest to her gave her the appreciative nickname "The Princess".[19] During the period as president, she was quite ill with "weak lungs" and told she only had six months to live. She was advised to travel to the south of France to recuperate.[19] She retired from Wellesley in June 1887.[2]

Palmer was awarded an honorary Ph.D. by the University of Michigan in 1882 and an honorary L.H.D. from Columbia University in 1887.[21]

Public speaker and advocate

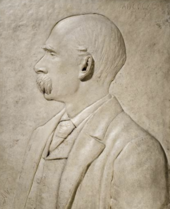

Daniel Chester French, Alice Freeman Palmer Memorial, Houghton Chapel, Wellesley College

She was a pioneer in the advancement of college education for women,[21] and the image of educated women. A national figure, she portrayed herself as a New Woman, and especially in Boston was seen as a "respected, financially independent, successful academic woman devoted to promoting women's education." She appeared in magazine and news stories and was requested for public speaking engagements. After she retired from Wellesley she also wrote articles for major magazines.[20]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

She labored earnestly in many paths to increase opportunities of service for college women, and in every field to choose for advancement those with capacity for leadership and scholarship, who should themselves become creators of new and larger opportunities for others.

— American Association of University Women[21]

In 1881, Palmer co-founded the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, which later became the American Association of University Women.[2][22] She would serve as its President from 1885 to 1887 and again from 1889 to 1890.[23]

From 1887 to 1889, the newlywed lectured about higher education for women. After working at the University of Chicago, she continued lecturing and advocating for women's education. She was appointed to the Massachusetts Board of education.[2] Palmer was the trustee of many organizations and worked to solve educational problems.[19] She resigned as trustee of one college when she learned at a young woman was refused admission because she was colored. The school modified its policy shortly after Palmer resigned.[24] In 1893, she helped organized the Woman's Building for the World's Fair in Chicago.[24]

Palmer received an honorary L.L.Ds in 1895 from Union College and the University of Wisconsin.[21]

She was a member of the Massachusetts State Board of Education from 1889 to 1902. From 1891 to 1901, she was the president of the Woman’s Education Association in Boston. She was General Secretary of the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, one of the chief executive officers of the Association for Promoting Scientific Research by Women, and President of the International Institute for Girls in Spain.[21]

University of Chicago

In 1892, Palmer accepted an offer by the president of the new University of Chicago as non-resident dean of the women's department[2][25][20] or the colleges and graduate schools.[19] Her husband had also been offered a position, but he decided to stay at Cambridge.[2]

She was required to be on-site for one third of the academic year. The goal of her office was to help students plan their educational career and create a social relationship between the university and its students.[19] During her time as dean of the women's department she doubled the percentage of the female students at the school from 24% to 48%, which resulted in a backlash from mainly male faculty members. Discouraged by the faculty and staff's response, she resigned in 1895.[2]

Personal life

Anne Whitney, Relief of George H. Palmer, 1896, Davis Museum, Wellesley College

She had a number of suitors while at the University of Michigan and as she began her career, but waited to pursue marriage until she was established in her career with a comfortable income.[26] Palmer had also been seen as the epitome of the New Woman, and so some people were content that she remained an independent unmarried woman.[20] During her time at Wellesley she met her future husband, George Herbert Palmer, who taught at Harvard University. She was engaged to marry George and resigned from her position at Wellesley College in June 1887[2] partly due to her poor health. She had early signs of tuberculosis and was exhausted. Her new husband also felt that she had already made major strides towards improving the university. She took a break to recuperate.[20]

Alice and George married on December 23, 1887[20] and she began to give public speeches on women's higher public education.[2] They had a "marriage of comradeship". They both pursued their individual careers, and George contributed efforts to managing the household, particularly when she was at the University of Illinois during her post there.[20]

While summering at her husband's home in Boxford, Massachusetts, she explored the local area, sewed, watched birds, and took up photography.[24] They took long trips to Europe over three of George's sabbaticals, during which they lived in their favorite cities and traveled through the countryside on bicycles.[24] She composed many beautiful poems,[25] some of which are found in Life of Alice Freeman Palmer and A Marriage Cycle.[27] In 1901, she wrote the hymn How sweet and silent is the place (Holy Communion).[28]

In December 1902, while the Palmers were in Paris on sabbatical, she complained of pains that required surgery to remove a bowel obstruction.[24]

Death

During convalescence following surgery, she died of a heart attack.[24] Palmer's life was commemorated at a service at Harvard University in 1903 attended by college presidents whom she knew and other notable individuals in higher education.

George Herbert Palmer retained her ashes until 1909, when a monument was erected by sculptor Daniel Chester French at Houghton Chapel in Wellesley College.[29] At his request, George's ashes were entombed beside his wife's in 1933.

Posthumous honors

1905 student body of the Alice Freeman Palmer Institute, founded by Charlotte Hawkins Brown in 1902 and named in memory of Palmer[30]

Alice Palmer Building, Palmer Memorial Institute, built in 1922

The Alice Freeman Palmer Institute, commonly called the Palmer Memorial Institute, was founded in Sedalia, North Carolina in 1902 for African-American students by Charlotte Hawkins Brown, who was sponsored for her education and mentored by Palmer. Brown saw Palmer shortly before her death when she was fundraising for the school. It was named for Palmer following her death in December.[30] In 1922, the school built the Alice Freeman Building, which held an auditorium, library, classes, and offices. It also had a collection of reproductions of art masterpieces, the first known school in the South for African-Americans to do so. In 1971, it was destroyed in a fire.[31]

In 1908, the first endowment at the AAUW was created in Palmer's memory to help women attend colleges, conduct research, and write dissertations.[32]

In 1920, Alice Freeman Palmer was elected to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans.

In 1921, Whittier College named a new women's literary society after her. The College had as its mission to create a female literary society, with the hope of bringing such groups back to Whittier College after they faded from existence at the beginning of World War I. Fullerton Junior College transfer Jessamynn West and friends reportedly researched and lobbied extensively to name the group for Alice Freeman Palmer, due to her reputation as a staunch advocate of higher education for women during the late 19th century. In the early years, the Palmer Society was an intercollegiate society that read and performed plays with the school's cross-town rival, Occidental College. Today, the Palmer Society's goal is still to "attain to the highest ideals of American womanhood."

In World War II, the United States liberty ship SS Alice F. Palmer was named in her honor.

References

^ ab Bordin 1993, pp. 15–17.

^ abcdefghijklmnopq Whittier.

^ ab Bordin 1993, pp. 17–18.

^ abc AAUW 1903, p. 1.

^ ab Bordin 1993, p. 18.

^ Bordin 1993, pp. 18–19.

^ Bordin 1993, pp. 19–20.

^ abc Bordin 1993, p. 23.

^ Bordin 1993, pp. 18, 21.

^ Bordin 1993, pp. 27–28.

^ Bordin 1993, pp. 26–27.

^ Bordin 1993, pp. 28–29.

^ ab Bordin 1993, p. 30.

^ Bordin 1993, pp. 23, 38.

^ abcd AAUW 1903, p. 2.

^ Bordin 1993, p. 24.

^ Bordin 1993, p. 74.

^ Bordin 1993, pp. 76, 156.

^ abcdefgh AAUW 1903, p. 3.

^ abcdefghi Massachusetts Moments.

^ abcde AAUW 1903, p. 4.

^ AAUW.

^ AAUW Journal 1911, p. 13.

^ abcdef James & James 1971, p. 8.

^ ab Hargittai & Hargittai 2016.

^ Bordin 1993, p. 157.

^ Alkalay-Gut 2008, p. 349.

^ Hazard 1907.

^ Wellesley News & June 16, 1909.

^ ab Burns-Vann & Vann 2004, pp. 50–51.

^ North Carolina Historic Sites.

^ UUAW.

Sources

American Association of University Women (AAUA). "Women in History Live On through Fellowships". AAUW.

American Association of University Women (AAUA) (1903). Alice Freeman Palmer: In Memoriam, MDCCCLV-MDCCCCII. Boston: Association of Collegiate Alumnæ. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

"List of Presidents". AAUW Journal. American Association of University Women. 1911. p. 13.

Alkalay-Gut, Karen (September 1, 2008). Alone in the Dawn: The Life of Adelaide Crapsey. University of Georgia Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-8203-3213-0.

Bordin, Ruth Birgitta Anderson (1993). Alice Freeman Palmer: The Evolution of a New Woman. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10392-X.

Burns-Vann, Tracey; André D. Vann (2004). Sedalia and the Palmer Memorial Institute. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-7385-1644-8.

Hargittai, István; Magdolna Hargittai (November 3, 2016). New York Scientific: A Culture of Inquiry, Knowledge, and Learning. Oxford Press. p. PT201. ISBN 978-0-19-108468-3.

Hazard, M.C. (1907). "Alice Freeman Palmer". Dictionary of Hymnology, New Supplement. Retrieved February 10, 2017 – via Hymnary.

Edward T. James; Janet Wilson James; Paul S. Boyer; Radcliffe College (1971). Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Harvard University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-674-62734-5.

Massachusetts Moments. "Alice Freeman and George Herbert Palmer Marry December 23, 1887". Massachusetts Moments. Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

North Carolina Historic Sites. "Charlotte Hawkins Brown Museum—The Alice Freeman Palmer Building". North Carolina Historic Sites. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

Wellesley News (June 16, 1909). "The Alice Freeman Palmer Memorial". The Wellesley News. 8 (31). Wellesley College. p. 5.

Whittier College. "Alice Freeman Palmer". web.whittier.edu.

Further reading

Brittanica (January 2008). "Palmer, Alice Elvira Freeman". Britannica Biographies. (Subscription required (help)).

Kenschaft, Lori J. (2005). Reinventing Marriage: The Love and Work of Alice Freeman Palmer and George Herbert Palmer. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03000-0.

Palmer, Alice Freeman; George Herbert Palmer (1940). An Academic Courtship: Letters of Alice Freeman and George Herbert Palmer, 1886–1887. Harvard University Press.

Palmer, George Herbert (1908). The Life of Alice Freeman Palmer. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Co.; Cambridge: Riverside Press.

George Herbert Palmer; Palmer, Alice Freeman (1908). The Teacher: Essays and Addresses on Education. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Schwartz, R. (February 2000). "Palmer, Alice Elvira Freeman". American National Biography Online. (Subscription required (help)).

External links

Works by Alice Freeman Palmer at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about Alice Freeman Palmer at Internet Archive