Algeciras Campaign

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP The Algeciras campaign (sometimes known as the Battle or Battles of Algeciras) was an attempt by a French naval squadron from Toulon under Contre-Admiral Charles Linois to join a French and Spanish fleet at Cadiz during June and July 1801 during the French Revolutionary War prior to a planned operation against either Egypt or Portugal. To reach Cadiz, the French squadron had to pass the British naval base at Gibraltar, which housed the squadron tasked with blockading the Spanish port. The British squadron was commanded by Rear-Admiral Sir James Saumarez. After a successful voyage between Toulon and Gibraltar, in which a number of British vessels were captured, the squadron anchored at Algeciras, a fortified port city within sight of Gibraltar across Gibraltar Bay. On 6 July 1801, Saumarez attacked the anchored squadron, in the First Battle of Algeciras. Although severe damage was inflicted on all three French ships of the line, none could be successfully captured and the British were forced to withdraw without HMS Hannibal, which had grounded and was subsequently seized by the French.

In the aftermath of the first battle, both sides set about making urgent repairs and calling up reinforcements. On 9 July a fleet of five Spanish and one French ship of the line and several frigates arrived from Cadiz to safely escort Linois's squadron to the Spanish port, and the British at Gibraltar redoubled their efforts to restore their squadron to fighting service. In the evening of 12 July the French and Spanish fleet sailed from Algeciras, and the British force followed them, catching the trailing ships in the Second Battle of Algeciras and opening fire at 11:20. A confused night action followed, in which the British ship HMS Superb cut through the disorganised allied rearguard, followed by the rest of Saumarez's force. In the confusion one French ship was captured, a Spanish frigate sank and two huge 112-gun Spanish first rates collided and exploded, killing as many as 1,700 men. The following morning the French ship Formidable came under attack at the rear of the combined squadron, but successfully drove off pursuit and reached Cadiz safely.

Ultimately the French and Spanish fleets were successful in their aim of uniting at Cadiz, albeit after heavy losses, but they were still under blockade and in no position to realise either the Egyptian or Portuguese plans. The two battles, "generally regarded as a single linked battle",[1] proved decisive in cementing British control of the Mediterranean Sea and condemning the French army in Egypt to defeat, totally unsupported by reinforcements from the French Navy.

Contents

1 Background

2 Linois's voyage

3 First Battle of Algeciras

4 Interlude

5 Second battle of Algeciras

6 Aftermath

7 Notes

8 References

9 Bibliography

Background

On 1 August 1798, a British fleet surprised and almost completely destroyed the French Mediterranean Fleet at the Battle of the Nile in the aftermath of the successful French invasion of Egypt. This immediately reversed the strategic situation in the Mediterranean Sea, eliminating the French fleet based at Toulon as a significant threat and granting the British and their allies in the War of the Second Coalition naval dominance in the region.[2] Over the next three years, British and allied squadrons enforced blockades against all significant French and Spanish naval bases in the region, including Alexandria, Corfu and Malta but particularly the significant harbours at Toulon and Cadiz. This drastically limited the movement of French troops and military materials across the Mediterranean, with the result that Malta and Corfu were captured and the army in Egypt was steadily reduced in size and effectiveness.[3]

In January 1801, in an attempt to increase the size of the French Mediterranean Fleet and to reinforce the beleaguered Egyptian garrison, First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte ordered a squadron of seven ships of the line to sail from Brest on the Atlantic coast to the Mediterranean under Rear-Admiral Honoré Ganteaume.[4] The squadron made three unsuccessful attempts to reach Egypt, eventually retiring to Toulon in late July 1801. During the final effort, Ganteaume's squadron sailed from Toulon on 27 April 1801 with instructions to briefly secure local naval supremacy around Elba to allow a seabourne invasion to go ahead, before travelling on into the Eastern Mediterranean.[5] During these operations, Ganteaume discovered that several ships in his force were dangerously undermanned, and therefore decided to consolidate his crews and send three ships of the line, Formidable, Indomptable and Desaix, and the frigate Créole back to Toulon.[6]

The presence of this force at Toulon enabled the French to plan a secondary operation using Ganteaume's new arrivals. A deal had been brokered earlier in the year between Bonaparte and Charles IV of Spain for the Spanish government to provide six ships of the line from the Cadiz fleet to the French Navy.[7] Orders were given that the new squadron at Cadiz was to be joined by the three ships of the line detached from Ganteaume's squadron, as well as the frigate Muiron under the overall command of Rear-Admiral Charles Linois.[8] This force of nine French ships, accompanied by six promised vessels from the Spanish fleet, was then to fulfil one of two mooted plans: the first was a large scale attack on Lisbon. Portugal and Spain were engaged in the War of the Oranges and Lisbon was a major British trading port: the French admiral Kerguelen had estimated some years earlier that an attack there could seize as much as "2 millions" of British goods and shipping.[9] The other planned operation, adopted following the end of the War of the Oranges on 2 June, was for the force to resupply Egypt using soldiers stationed at Italian ports.[9] To facilitate the transfer of the Spanish ships to French control, Napoleon ordered Contre-Admiral Pierre Dumanoir le Pelley to sail to Cadiz. Le Pelley arrived at the Spanish port on 13 June in the frigates Libre and Indienne with sailors to begin manning the newly purchased ships and Commodore Julien le Ray to command them. His arrival was noted by the British blockade squadron off Cadiz under Rear-Admiral Sir James Saumarez, a veteran of the Battle of the Nile and one of Lord Nelson's famous "Band of Brothers":[10] Le Pelley's ships were chased by HMS Superb and HMS Venerable, but the French admiral managed to evade his pursuers and reach Cadiz safely.[11] Saumarez had been ordered to Cadiz in May 1801 with orders not only to blockade the Spanish fleet, but also specifically to watch for an attempt by a French squadron to link with the Spanish fleet at Cadiz.[12]

Linois's voyage

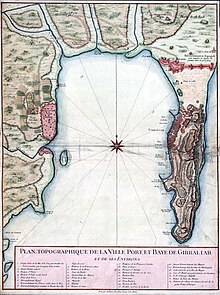

A map of the Bay of Gibraltar, c.1750, showing Algeciras (left) and Gibraltar; there is roughly 10 km (5.4 nmi; 6.2 mi) of open water between them.

Linois sailed from Toulon on 13 June 1801 with three ships of the line and one frigate carrying 1,560 soldiers under Brigadier-General Devaux.[13] Ganteaume's earlier expedition was still in the Eastern Mediterranean, and so the British blockade force under Sir John Borlase Warren detailed to watch Toulon was instead off Malta hoping to intercept Ganteaume on his return.[14] Therefore, the only British ships on hand when Linois emerged from the port were a few frigates, which were easily chased away by the larger warships of the French squadron. Linois's passage was slow, facing winds from the southwest that delayed his squadron so that by 30 June they were only off Cape de Gata in the Alboran Sea. On 1 July they were spotted from Gibraltar, although the only warship there was the 14-gun HMS Calpe under Captain George Dundas which was unable to influence their advance. Instead, Captain Dundas ordered Lieutenant Richard Janvarin to take a boat and communicate with the Cadiz blockade force of seven ships of the line, under Saumarez.[8]

Linois passed Gibraltar on 3 July and during the night discovered the 14-gun brig HMS Speedy a short distance ahead. Linois's squadron had captured a number of merchant vessels during their voyage but this was their first warship, and although it was no match for size, Speedy was an infamous vessel under the command of Captain Lord Cochrane. Cochrane had spent the last year raiding the Spanish coast with great success, taking or destroying more than 50 ships including the celebrated Action of 6 May 1801 in which Cochrane had attacked and captured the far larger Spanish privateer frigate Gamo off Barcelona.[15] Cochrane's initial belief that the strange ships were Spanish treasure vessels caused him to bring Speedy closer to the ships and by the time he realised his error escape was impossible.[16] Rather than surrender however, Cochrane threw all of his guns and excessive weight overboard and manoeuvered his ship to avoid coming into range of the French broadsides. He then attempted to cut directly between the approaching Formidable and Desaix, the small target avoiding the concentrated fire of the French ships and pulling into open water. At this, Commodore Jean-Anne Christy-Pallière on Desaix swung his ship about and pursued, several shots damaging Speedy's sails and rigging. As Speedy slowed, Desaix overtook the small brig and fired a full broadside at close range.[17] This was fired as the French ship was on the uproll and therefore missed the deck entirely and failed to cause a single casualty. It did however tear away the remaining rigging and sails, leaving Speedy unmanageable. Rather than suffer another broadside, Cochrane surrendered his ship and was taken aboard Desaix, where Christy-Pallière acknowledged his brave defence by refusing to accept Cochrane's surrendered sword with the words "I will not accept the sword of an officer who has for so many hours struggled against impossibility".[18] From Cochrane, Linois learned of Saumarez's presence ahead of him and, knowing that his presence would have been reported by the garrison at Gibraltar,[19] his squadron returned eastwards around Cabrita Point and came to anchor at Algeciras, a fortified Spanish port which lay directly opposite and within sight of Gibraltar across the Bay of Gibraltar on 4 July.[7]

Off Cadiz, the squadron under Saumarez was notified of Linois's arrival by Lieutenant Janvarin at 02:00 on 5 July and immediately turned back towards Gibraltar, tacking against the wind. The frigate HMS Thames was detached and sent 18 nautical miles (33 km) westwards to the mouth of the Guadalquivir River to collect HMS Superb under Captain Richard Goodwin Keats, which was blockading the river with the small brig HMS Pasley.[20] Keats did follow Saumarez back to Algeciras, and was in distantly in sight when the battle commenced, but on hearing an inaccurate report from an American merchant ship that Linois had escaped the bay and was at sea once more, Keats reasoned that the French must be returning to Toulon and that he would be in a better position returning to the blockade of Cadiz than attempting to join Saumarez's chase.[21] The lugger HMS Plymouth was also detached to Lisbon with despatches for the Admiralty informing them of Saumarez's intentions.[12] The British admiral, knowing that Linois was still anchored in the bay, intended to descend on Algeciras immediately but was beset by a series of calm spells that prevented his squadron from doing more than slowly drifting eastwards away from Superb and towards Algeciras. It was not until the morning of 6 July therefore that Saumarez was in a position to attack the anchored French squadron.[22] In anticipation of Saumarez's arrival, Linois had formed his squadron into a strong defensive position, the three ships of the line anchored in a line north to south across in shallow waters off the mouth of Algeciras harbour, protected by Spanish forts at either extremity and around the town itself, where Murion was anchored in shallower water. Linois led the line himself in Formidable, but despatched parties from the crews of the ships of the line to augment the Spanish defences.[22]

First Battle of Algeciras

Algéciras, 6 Juillet 1802, Alfred Morel-Fatio

At 07:00, Saumarez ordered his squadron to advance into the bay without delay and engage the French directly, the attack to be led by Captain Samuel Hood in HMS Venerable. Hood was delayed by light winds however, and the first ship into action was HMS Pompée under Captain Charles Stirling, which attacked the anchored French ships in succession before anchoring close to Formidable.[23]Pompée was followed by HMS Audacious, Saumarez's flagship HMS Caesar and HMS Hannibal, with Venerable and HMS Spencer participating at a greater distance due to the unreliable wind.[24] By 10:00 both squadrons were fully engaged except for Pompée at the head of the British line which had been caught by a current and swung so that the ship's bow was facing Formidable's broadside, allowing Linois to rake the British ship.[25] Seeing the danger Stirling was in, Saumarez ordered Captain Solomon Ferris to take Hannibal around the head of the French line and rake Formidable. In the light wind, Ferris took almost an hour to reach the head of the lines, but as he turned inshore, Hannibal grounded on a shoal directly under the guns of the Spanish fort at Torre de Almirante.[26]

Saumarez ordered his squadron's boats to assist Hannibal and Pompée, both of which were trapped under heavy fire and unable to effectively respond.[26] As he did so, Linois ordered his ships to cut their anchor cables and drift into the shallows, away from the becalmed British squadron. Formidable successfully completed the manoeuvre, but both Desaix and Indomptable grounded inshore, where they were exposed to heavy fire from Saumarez's ships, which had also cut their cables in an effort to close with their opponents.[27] At 13:35 however, Saumarez recognised that his squadron was in danger of grounding directly under the fire of the Spanish batteries. With the squadron's boats either sunk or employed towing Pompée back to Gibraltar, there was no possibility of launching an amphibious operation against the Spanish forts and Saumarez reluctantly called the attack off, the remainder of the squadron retiring to Gibratar but leaving the stranded Hannibal in the Bay of Gibraltar.[28]

Hannibal had been exposed to the combined French and Spanish fire for four hours, and had lost two masts and more than 140 men killed and wounded. In an effort to preserve the lives of his crew, Ferris ordered his men to shelter below decks, but at 14:00 fires broke out on the ship and Ferris, isolated by Saumarez's withdrawal, surrendered his ship.[29] French boarding parties extinguished the fires and rehung the struck ensign upside down to signify that Hannibal had surrendered. However, in the Royal Navy an inverted flag is a signal of distress, and at least one British ship's boat was captured while attempting to bring assistance to Ferris before the misunderstanding was realised.[30]

The French victory had come at a heavy cost: more than 160 men were killed and 300 wounded and all three French ships had been severely damaged.[Note A] Among the dead were the captains of both Formidable and Indomptable, although Linois was unhurt.[31] The Spanish had suffered eleven men killed and five gunboats had been destroyed. The batteries and town had also been badly damaged in the fighting.[32] British losses were also heavy, with more than 130 killed and more than 230 wounded, most of which had been lost on Hannibal and Pompée. In addition to the loss of Hannibal, Pompée was severely damaged and the remainder of the British squadron all required urgent repairs.[30]

Interlude

Immediately following the battle, Linois used overland messengers to request the assistance of the Spanish fleet at Cadiz under Admiral Jose de Mazzaredo.[33] Linois and Saumarez also embarked on a program of refitting and repairing their damaged squadrons in preparation for a resumption of the action. At Gibraltar, the wounded were transferred to the naval hospital and the dead buried in the gravesite later to be known as Trafalgar Cemetery.[34] Saumarez ordered that the most damaged of the surviving ships, Pompée and Caesar, be laid up in dock and their crews distributed among the remaining ships to ensure that they could be repaired as rapidly as possible, a situation made necessary in part due to the seizure of many of Gibraltar's shipwrights in the Bay of Gibraltar when they were sent to aid Hannibal in the last stages of the battle.[35] The entire squadron needed extensive repairs, their requirements met by Captain Alexander Ball, naval commissioner at Gibraltar.[36] Captain Jahleel Brenton of Caesar protested this order and Saumarez permitted him to continue with repairs: Caesar's crew worked all day and in regular shifts throughout the night for the next week to ensure that when Saumarez sailed again, Caesar sailed with him, the crew having replaced the ship's damaged masts in just four days.[37] Saumarez also sent a boat under a flag of truce in to Algeciras to arrange for the repatriation under parole of Ferris and his officers. Following a brief correspondence between Linois and the British admiral, the captured British officers, including Ferris and Cochrane, were sent to Gibraltar, later joined by the wounded British sailors captured on Hannibal.[38] Ferris was immediately sent to Britain on HMS Plymouth with despatches, to await the court-martial for the loss of his ship.[39] He and his officers were completely exonerated.[11]

Linois also began a programme of refloating and making extensive repairs to his ships, including the captured Hannibal, which he renamed Annibal. Jury masts were set up on the battered hulk, although such extensive repairs were required that when Linois sailed a week later the ship was still only just seaworthy, and was sent back to Algeciras.[40] In Cadiz, despite Spanish hesitation, the messages from Linois coupled with strong representations from le Pelley prompted Mazzaredo to order a squadron to sea on the morning of 9 July, commanded by Vice-Admiral Don Juan Joaquin de Moreno and including two very large first rate ships of the line: Real Carlos and San Hermenegildo, each mustering 112 guns.[41] The remainder of the squadron consisted of a 96-gun Spanish ship, an 80-gun Spanish ship, a 74-gun Spanish ship as well as the 74-gun ship Saint Antoine, which a few days earlier had been the Spanish San Antonio. The first of the purchased ships of the line to be commissioned into the French Navy, Saint Antoine's crew was drawn from the men brought to Cadiz on the frigates Libre and Indienne, supplemented by a number of Spanish sailors and commanded by Commodore Le Ray. Accompanying the squadron were the frigates Libre, the Spanish Sabina and the French lugger Vautour.[40]

The departure of this combined squadron was observed by Captain Keats on Superb, which after returning to Cadiz had retained station off the port with HMS Thames and HMS Pasley. Thames was inshore searching a seized American merchant ship, and witnessed the emergence of the squadron, retreating before four ships of the line that approached the British frigate. Superb was sighted shortly afterwards and also retreated before a ship of the line and two frigates, reconstituting his small squadron in the wake of Moreno's force.[42] Keats immediately sent Pasley ahead to Gibraltar to warn Saumarez, the brig arriving at 15:00 closely followed by the main body of the combined squadron, from which Saint Antoine had detached during the departure from Cadiz and was following behind, shadowed by Superb.[41] Moreno's squadron anchored in the Bay of Gibraltar, out of reach of the British batteries on Gibraltar and waited there for Linois to complete his repairs, Saint Antoine joining the squadron on the morning of 10 July.[43] Keats then brought his ships into Gibraltar, where efforts to repair the squadron were increased, with the knowledge that Moreno would soon be sailing to Cadiz with Linois squadron.[35] Saumarez, concerned by the size of the combined squadron, sent urgent messages to the Mediterranean Fleet under Lord Keith in the Eastern Mediterranean requesting support in the belief that Moreno would be delayed at least two weeks due to the condition of Linois's ships.[36] Saumarez was wrong: Moreno planned to convoy the battered squadron the short distance to Cadiz as soon as they were seaworthy.

Second battle of Algeciras

HMS Superb sails silently off the Spanish fleet at Gibraltar Bay, while the Hermenegildo and Real Carlos explode in the background after mistakenly firing on one other. Drawing by Antoine Léon Morel-Fatio.

On the morning of 12 July the combined French and Spanish squadron put to sea, followed closely by the British squadron. Both sides took most of the day to assemble, hampered by light winds and damaged warships, but at 19:00 Moreno gave orders for his squadron to make all sail westwards towards the open ocean and Cadiz. Saumarez followed, but at 20:40, with night drawing in and the wind picking up, he instructed Keats to take Superb, the fastest ship in his squadron, ahead and engage the rearguard of Moreno's force.[7] At 23:20, Keats discovered the Real Carlos and pulled alongside, firing three broadsides into the Spanish ship that started a severe fire. Superb then pushed on towards Saint Antoine while Real Carlos drifted in darkness and confusion, encountering San Hermenegildo, the Spanish ships mistaking one another for an enemy and opening fire. Real Carlos then drifted into San Hermenegildo, the huge ships tangling together and the fire spreading from one to another until both were blazing wrecks in the darkness. They both exploded at 00:15 on 13 July, killing more than 1,700 men.[44] At some stage during the night, the independently sailing Spanish frigate Perla sailed through the battle and was fatally damaged in the crossfire, sinking the next morning.[45]

Keats meanwhile had engaged and defeated Saint Antoine, forcing the wounded Commodore Julien le Ray to surrender following an action that had lasted just half an hour. Casualties on Saint Antoine were heavy, although Superb had just 15 men wounded. The rest of the British squadron, following up in the darkness, mistook Saint Antoine as being still active, and all fired on the ship as they passed, intending to catch the remainder of Moreno's squadron as it sailed northwest along the Spanish coastline.[46] At 04:00 the Formidable, now under the command of Captain Amable Troude, was seen to the north in Conil Bay near Cape Trafalgar and Saumarez sent Venerable to chase the French ship, Hood accompanied by Thames under Captain Aiskew Hollis. At 05:15, Venerable came within range and a close action soon followed, Hood ordering Hollis to bring his ship close to Troude's stern and open up a raking fire. Formidable had the better of the action however and at 06:45, with casualties mounting, Hood's mainmast collapsed over the side.[47]

Beau fait d'armes du capitaine Troude, Alfred Morel-Fatio

Taking advantage of the disability to the British ship, Troude pulled Formidable ahead in light winds, slowly rejoining the main squadron under Moreno, which was holding station off Cadiz harbour.[48] As Formidable moved away, the remaining masts on Venerable collapsed and the ship grounded off Sancti Petri. There was concern in the British squadron that Moreno might counterattack the disabled ship, but the arrival on the horizon of Audacious and Superb persuaded the Spanish admiral to withdraw into Cadiz.[44] Hood was able to refloat Venerable on 13 July and the ship was towed back to Gibraltar with the prize Saint Antoine. Saumarez left three ships to maintain the blockade at Cadiz, returning the situation off the port to that before the battle.[49]

Aftermath

In France the campaign was represented as a victory, as Linois' genuine achievements at Algeciras were followed by exaggerated reports of Troude's defence in Conil Bay in which the second battle was represented as a significant success against a more numerous British force. Troude had shown skill and bravery in the engagement, but his subsequent reputation was largely built on the strength of a report sent to Paris by Dumanoir le Pelley which was based on a letter written by Captain Troude. In the letter, he claimed that he had fought not only Venerable and Thames, but also Caesar and Spencer (misidentified in the report as Superb).[50] Troude stated that he had not only driven all of these ships off, but that he had also completely destroyed Venerable by driving the ship ashore. Troude was subsequently promoted and highly praised, holding a number of important active commands in the French Navy.[51] In Spain, the outcome of the campaign infuriated the Spanish government and contributed to the souring of the Franco-Spanish alliance. The Spanish demanded that the Spanish forces then stationed at Brest on the French Atlantic coast return to Spanish waters, and Spanish pressure on Portugal was relaxed. This weakening of the Franco-Spanish axis was a significant factor in the Treaty of Amiens in early 1802 that brought the French Revolutionary Wars to a close.[52]

Saumarez was lauded in Britain, the success of the second action mitigating the initial defeat. He was awarded the thanks of both Houses of Parliament and made a Knight of the Bath with a pension of £1,200 annually (the equivalent of £84,000 as of 2018).[53].[49] Nearly five decades later, the second battle (although not the first) was among the actions recognised by the Naval General Service Medal, awarded upon application to all British participants still living in 1847.[54] The campaign later played a prominent part in the novels Master and Commander by Patrick O'Brian and Touch and Go by C. Northcote Parkinson.[55][56] In British histories the campaign is usually considered a single linked battle, with the overall outcome favourable to the British force, despite the failure to prevent Linois from linking with Cadiz and the loss of Hannibal.[1] The severe losses inflicted on the Spanish fleet at Cadiz and the reinstatement of the blockade meant that the French plan to reinforce the army trapped in Egypt was a total failure, the garrison there surrendering in September after a hard-fought campaign against British and Ottoman forces.[57] It also emphasised British dominance at sea by this stage of the war, reiterating that no force could sail from a French or allied port without detection and interception by the Royal Navy.[58]

Notes

^ Note A: Reports of French casualties in the first battle vary widely. James and Clowes quote French reports of 306 killed and 280 wounded in total and Spanish reports that the French suffered 500 wounded.[31][32] However in his breakdown of French casualties ship by ship, Musteen only records 161 killed and 324 wounded.[34]

References

^ ab Mostert, p. 408

^ Gardiner, p. 58

^ Gardiner, p. 16

^ James, p. 87

^ Woodman, p. 158

^ James, p. 93

^ abc Woodman, p. 161

^ ab Clowes, p. 459

^ ab James, p. 112

^ Sainsbury, A. B. "Saumarez, James". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

^ ab James, p. 123

^ ab Musteen, p. 33

^ Clowes, p. 458

^ James, p. 113

^ Lambert, Andrew. "Cochrane, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

^ Adkins, p. 92

^ Harvey, p. 58

^ Harvey, p. 59

^ Musteen, p. 32

^ Clowes, p. 460

^ James, p. 124

^ ab Mostert, p. 404

^ James, p. 115

^ Clowes, p. 461

^ James, p. 116

^ ab Clowes, p. 463

^ James, p. 117

^ Gardiner, p. 89

^ Mostert, p. 405

^ ab Clowes, p. 464

^ ab Clowes, p. 465

^ ab James, p. 119

^ Gardiner, p. 91

^ ab Musteen, p. 41

^ ab Mostert, p. 406

^ ab Musteen, p. 43

^ James, p. 125

^ James, p. 122

^ Musteen, p. 45

^ ab James, p. 126

^ ab Clowes, p. 466

^ Musteen, p. 42

^ Gardiner, p. 92

^ ab Gardiner, p. 93

^ James, p. 354

^ James, p. 128

^ Clowes, p. 468

^ James, p. 129

^ ab James, p. 130

^ James, p. 131

^ Clowes, p. 469

^ Rodger, p. 472

^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 240.

^ O'Brian, Patrick, Master and Commander, 1969, Harper Collins, ISBN 0006499155

^ Parkinson, C. Northcote, Touch and Go, 1978, Littlehampton Books, ISBN 0417024606

^ Mostert, p. 409

^ Clowes, p. 470

Bibliography

Adkins, Roy & Lesley (2006). The War for All the Oceans. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11916-8.

Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

Gardiner, Robert (editor) (2001) [1996]. Nelson Against Napoleon. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-86176-026-4. CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Harvey, Robert (2000). Cochrane: The Life and Exploits of a Fighting Captain. Constable. ISBN 1-84119-162-0.

James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 3, 1800–1805. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-907-7.- Mostert, Noel (2007). The Line upon a Wind: The Greatest War Fought at Sea Under Sail 1793–1815. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-7126-0927-2.

- Musteen, Jason R. (2011). Nelson's Refuge: Gibraltar in the Age of Napoleon. Naval Investiture Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-545-5.

Rodger, N.A.M. (2004). The Command of the Ocean. Allan Lane. ISBN 0-71399-411-8.

Woodman, Richard (2001). The Sea Warriors. Constable Publishers. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.