Zoning

The Zoning Scheme of the General Spatial Plan for the City of Skopje, Republic of Macedonia. Different urban zoning areas are represented by different colors.

Zoning is the process of dividing land in a municipality into zones (e.g. residential, industrial) in which certain land uses are permitted or prohibited.[1] In addition, the sizes, bulk, and placement of buildings may be regulated. The type of zone determines whether planning permission for a given development is granted. Zoning may specify a variety of outright and conditional uses of land. It may also indicate the size and dimensions of land area as well as the form and scale of buildings. These guidelines are set in order to guide urban growth and development.[2][3]

Areas of land are divided by appropriate authorities into zones within which various uses are permitted.[4]

Thus, zoning is a technique of land-use planning as a tool of urban planning used by local governments in most developed countries.[5][6][7] The word is derived from the practice of designating mapped zones which regulate the use, form, design and compatibility of development. Legally, a zoning plan is usually enacted as a by-law with the respective procedures. In some countries, e. g. Canada (Ontario) or Germany, zoning plans must comply with upper-tier (regional, state, provincial) planning and policy statements.

There are a great variety of zoning types, some of which focus on regulating building form and the relation of buildings to the street with mixed-uses, known as form-based, others with separating land uses, known as use-based or a combination thereof.

Similar urban planning methods have dictated the use of various areas for particular purposes in many cities from ancient times.

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 uldisplay:none

Contents

1 Scope

2 Origins

3 Types

3.1 Land use zoning

3.2 Economic explanation of population density regulations

3.3 Single-use zoning

3.3.1 Criticisms

4 Zoning laws by country

4.1 United States

4.1.1 Scale

4.1.2 Types

4.1.3 Reception

4.2 Canada

4.3 United Kingdom

4.4 Australia

4.5 New Zealand

4.6 Singapore

4.7 Japan

4.8 Philippines

4.9 France

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Scope

The primary purpose of zoning is to segregate uses that are thought to be incompatible. In practice, zoning also is used to prevent new development from interfering with existing uses and/or to preserve the "character" of a community. However, it has not always been an effective method for achieving this goal.[8] Zoning is commonly controlled by local governments such as counties or municipalities, though the nature of the zoning regime may be determined or limited by state or national planning authorities or through enabling legislation.[9] In Australia, land under the control of the Commonwealth (federal) government is not subject to state planning controls. The United States and other federal countries are similar. Zoning and urban planning in France and Germany are regulated by national or federal codes. In the case of Germany this code includes contents of zoning plans as well as the legal procedure.

Zoning may include regulation of the kinds of activities which will be acceptable on particular lots (such as open space, residential, agricultural, commercial or industrial), the densities at which those activities can be performed (from low-density housing such as single family homes to high-density such as high-rise apartment buildings), the height of buildings, the amount of space structures may occupy, the location of a building on the lot (setbacks), the proportions of the types of space on a lot, such as how much landscaped space, impervious surface, traffic lanes, and whether or not parking is provided. In Germany, zoning includes an impact assessment with very specific greenspace and compensation regulations and may include regulations for building design. The details of how individual planning systems incorporate zoning into their regulatory regimes varies though the intention is always similar. For example, in the state of Victoria, Australia, land use zones are combined with a system of planning scheme overlays to account for the multiplicity of factors that impact on desirable urban outcomes in any location.

Most zoning systems have a procedure for granting variances (exceptions to the zoning rules), usually because of some perceived hardship caused by the particular nature of the property in question.

Origins

The origins of zoning districts can be traced back to antiquity. The ancient walled city was the predecessor for classifying and regulating land, based on use. Outside the city walls were the undesirable functions, which were usually based on noise and smell; that was also where the poorest people lived. The space between the walls is where unsanitary and dangerous activities occurred such as butchering, waste disposal, and brick-firing. Within the wall were civic and religious places, where the majority of people lived.[10]

Beyond the simple distinction between urban and non-urban land, most ancient cities further classified land type and use inside their walls. That was practiced in many regions of the world. For example, in China during the Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 256 BC), in India during the Vedic Era (1500 – 500 BC), and in the military camps that spread throughout the Roman Empire (31 BC – 476 AD). As the residential districts made up the majority of the city, that early form of districting was usually along ethnic and occupational divides; generally, class or status diminished outwards from the city center. One legal form for enforcing it was the caste system.[10]

While space was carved out for important public institutions, places of worship, markets and squares, there is a major distinction between cities of antiquity and cities of today. Throughout antiquity and up until the onset of the Industrial Revolution (1760 - 1840), most work took place within the home. Therefore, residential areas also functioned as places of labor, production, and commerce. The definition of home was tied to the definition of economy, which caused a much greater mixing of uses within the residential quarters of cities.[11]

Throughout the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, cultural and socio-economic shifts led to the rapid increase in the enforcement in and the invention of urban regulations.[10] The shifts were informed by a new scientific rationality, the advent of mass production and complex manufacturing, and the subsequent onset of urbanization. Industry leaving the home was one major factor in reshaping industrial cities.

Overcrowding, pollution, and the urban squalor associated with factories were major concerns that led city officials and planners to consider the need for functional separation of uses. It was in France, Germany, and Britain that the first pseudo-zoning was invented to prevent polluting industries to be built in residential areas. It was Germany that invented modern zoning, in the late-19th century.[12]

Types

The theoretical and practical application of zoning can be divided into categories. Countries around the world utilize different types of zoning.

Land use zoning

Basically, urban zones fall into one of five major categories: residential, mixed residential-commercial, commercial, industrial and spatial (e. g. power plants, sports complexes, airports, shopping malls etc.). Each category can have a number of sub-categories, for example, within the commercial category there may be separate zones for small-retail, large retail, office use, lodging and others, while industrial may be subdivided into heavy manufacturing, light assembly and warehouse uses. In Germany, each category has a designated limit for noise emissions (not part of the building code, but federal emissions code).

In the United States or Canada, for example, residential zones can have the following sub-categories:

- Residential occupancies containing sleeping units where the occupants are primarily transient in nature, including: boarding houses, hotels, motels

- Residential occupancies containing sleeping units or more than two dwelling units where the occupants are primarily permanent in nature, including: apartment houses, boarding houses, convents, dormitories.

- Residential occupancies where the occupants are primarily permanent in nature and not classified as Group R-1, R-2, R-4 or I, including: buildings that do not contain more than two dwelling units, adult care facilities for five or fewer persons for less than 24 hours.

- Residential occupancies where the buildings are arranged for occupancy as residential care/assisted living facilities including more than five but not more than 16 occupants.

Conditional zoning allows for increased flexibility and permits municipalities to respond to the unique features of a particular land use application. Uses which might be disallowed under current zoning, such as a school or a community center can be permitted via conditional use zoning.

Economic explanation of population density regulations

Rothwell and Massey suggests homeowners and business interests are the two key players in density regulations that emerge from a political economy.[13] They propose that in older states where rural jurisdictions are primarily composed of homeowners, it is the narrow interests of homeowners to block development because tax rates are lower in rural areas, and taxation is more likely to fall on the median homeowner. Business interests are unable to counteract the homeowners' interests in rural areas because business interests are weaker and business ownership is rarely controlled by people living outside the community. This translates into rural communities that have a tendency to resist development by using density regulations to make business opportunities less attractive.

Single-use zoning

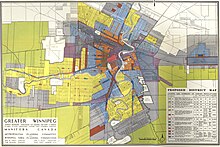

Example of Single-Use Zoning Regulations (Greater Winnipeg District Map, 1947)

Single-use zoning, also known as Euclidean zoning, is a tool of urban planning that controls land uses in a city. The earliest forms of single-use zoning were practiced in New York city in the early 1900s, to guide its rapid population growth from immigration.[14] Land uses were divided into residential, commercial and industrial areas, now referred to as zones or zoning districts in cities. Single-use zoning became known as Euclidean zoning because of a court case in Euclid, Ohio, which established its constitutionality, Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co. 272 U.S. 365 (1926).

Euclidean zoning has been the dominant system of zoning in much of North America since its first implementation.[15] The predictable model for dividing land use patterns generated by the Euclidean system have been charged by many commentators as playing a direct role in a number of problems in land use planning evident in the United States and elsewhere. Single-use zoning is a basic model that has not evolved to create appropriate solutions for the increasing complexity of social, political and environmental challenges in cities.[14]

Problems affiliated with Euclidean-style zoning policy include urban sprawl, urban decay, environmental pollution, racial and socioeconomic segregation, negative economic impacts and an overall reduced quality of life.[16][17] Land use regulations associated with a high separation of land uses have also been criticized as being fraught with legal obstacles to rehabilitating neighbourhoods affected by the aforementioned problems [16] (such efforts are often referred to as urban rehabilitation or urban renewal).

Euclidean zoning represents a functionalist way of thinking that uses mechanistic principles to conceive of the city as a fixed machine. This conception is in opposition to the view of the city as a continually evolving organism or living system, as first espoused by the German urbanist Hans Reichow.

Criticisms

Planning and community activist Jane Jacobs wrote extensively on the connections between Euclidean zoning and the destruction and displacement of communities in New York City. Her work details how conventional zoning often leads to the decay of municipal infrastructure and social capital and perpetuates brutal cycles of poverty and chronic under-funding in certain neighbourhoods.[18][page needed] Jacob's writings, along with increasing public dissatisfaction with the attendant problems of urban sprawl, is often credited with inspiring the New Urbanism movement and the ensuing body of literature concerned with solutions to uneven city development.

Critics argue that putting everyday uses out of walking distance of each other leads to an increase in traffic since people have to get in their cars and drive to meet their needs throughout the day. Single-zoning and urban sprawl have also been criticized as making work–family balance more difficult to achieve, as greater distances need to be covered in order to integrate the different life domains.[19]

Zoning laws by country

United States

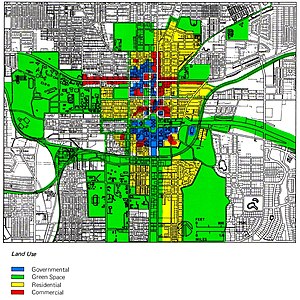

Zoning scheme of the center of Tallahassee, United States.

Under the police power rights, state governments may exercise over private real property. With this power, special laws and regulations have long been made restricting the places where particular types of business can be carried on. In 1904, Los Angeles established the nation's first land-use restrictions for a portion of the city.[20][21] In 1916, New York City adopted the first zoning regulations to apply citywide as a reaction to The Equitable Building which towered over the neighboring residences, diminishing the availability of sunshine. These laws set the pattern for zoning in the rest of the country. New York City went on to develop ever more complex regulations, including floor-area ratio regulations, air rights and others for specific neighborhoods.

The constitutionality of zoning ordinances was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1926 case Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co. Among large populated cities in the United States, Houston is unique in having no zoning ordinances.[22] Rather, land use is regulated by other means.[23]

Scale

Early zoning practices were subtle and often debated. Some claim the practices started in the 1920s[24] while others suggest the birth of zoning occurred in New York in 1916.[25] Both of these examples for the start of zoning, however, were urban cases. Zoning becomes an increasing legal force as it continues to expand in its geographical range through its introduction in other urban centres and use in larger political and geographical boundaries. Regional zoning was the next step in increased geographical size of areas under zoning laws.[26] A major difference between urban zoning and regional zoning was that "regional areas consequently seldom bear direct relationship to arbitrary political boundaries".[26] This form of zoning also included rural areas which was counter-intuitive to the theory that zoning was a result of population density.[26] Finally, zoning also expanded again but back to a political boundary again with state zoning.[26]

Types

Zoning codes have evolved over the years as urban planning theory has changed, legal constraints have fluctuated, and political priorities have shifted. The various approaches to zoning can be divided into four broad categories: Euclidean, Performance, Incentive, and form-based.

Named for the type of zoning code adopted in the town of Euclid, Ohio, and approved in a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co.[27]Euclidean zoning codes are the most prevalent in the United States.[28] Euclidean zoning is characterized by the segregation of land uses into specified geographic districts and dimensional standards stipulating limitations on development activity within each type of district. Advantages include relative effectiveness, ease of implementation, long-established legal precedent, and familiarity. However, Euclidean zoning has received criticism for its lack of flexibility and institutionalization of now-outdated planning theory.

Also known as "effects-based planning", performance zoning uses performance-based or goal-oriented criteria to establish review parameters for proposed development projects. Performance zoning is intended to provide flexibility, rationality, transparency and accountability, avoiding the arbitrariness of the Euclidean approach and better accommodating market principles and private property rights with environmental protection. Difficulties included a requirement for a high level of discretionary activity on the part of the supervising authority. Performance zoning has not been widely adopted in the USA.

First implemented in Chicago and New York City, incentive zoning is intended to provide a reward-based system to encourage development that meets established urban development goals.[29] Typically, the method establishes a base level of limitations and a reward scale to entice developers to incorporate the desired development criteria.

Incentive zoning allows a high degree of flexibility, but can be complex to administer.

Form-based codes offer considerably more governmental latitude in building uses and form than do Euclidean codes. Form-based zoning regulates not the type of land use, but the form that land use may take. For instance, form-based zoning in a dense area may insist on low setbacks, high density, and pedestrian accessibility. FBCs are designed to directly respond to the physical structure of a community in order to create more walkable and adaptable environments.[30]

Reception

Much criticism of zoning laws comes from those who see the restrictions as a violation of individuals' property rights. With zoning, a property owner may not be able to use her land for her desired purpose.

Along with potential property right infringements, zoning has also been criticized as a means to promote social and economic segregation through exclusion. These exclusionary zoning measures artificially maintain high housing costs through various land-use regulations such as maximum density requirements. Thus, lower income groups deemed undesirable are effectively excluded from the given community. "Although markets allocate people to housing based on income and price, political decisions allocate housing of different prices to different neighbourhoods and thereby turn the market into a mechanism for class segregation."(Rothwell and Massey 2010, p. 1141). In the American South, zoning was introduced as an explicit mechanism for enforcing racial segregation of communities. Southern planners coordinated with Northern experts in crafting racial zoning laws that would fit within the emerging judicial precedent. Racial zoning laws followed the migration of Southern blacks northward and westward.[31]

Examples of class or income segregation in the United States can be seen by comparing poverty rates in the central city and the suburbs in the West, the South, the Northeast, and the Midwest. The Northeast and the Midwest have more restrictive anti-density regulations. The lower incidence of poverty in the cities of the West and South and the higher incidence in the suburbs are associated with their more relaxed anti-density regulations [24]

Jonathan Rothwell has argued that zoning encourages racial segregation.[13] He claims a strong relationship exists between an area's allowance of building housing at higher density and racial integration between blacks and whites in the United States.[13] The relationship between segregation and density is explained by Rothwell and Massey as the restrictive density zoning producing higher housing prices in white areas and limiting opportunities for people with modest incomes to leave segregated areas.[13] Between 1980 and 2000, racial integration occurred faster in areas that did not have strict density regulations than those that did.[13]

Some economists claim that zoning laws work against economic efficiency and hinder development in a free economy, as poor zoning restrictions hinder the more efficient usage of a given area. Even without zoning restrictions, a landfill, for example, would likely gravitate to cheaper land and not a residential area. Strict zoning laws can get in the way of creative developments like mixed-use buildings and can even stop harmless activities like yard sales.[32] Broadly speaking, if workers were able to move around as freely as they could in 1964, US GDP would be 13.5%, or nearly $2 trillion, higher.[33]

Another issue with excessively strict zoning laws is that it may increase travelling distances, therefore increasing traffic congestion, fossil fuel use, and pollution. For example, a person inside a large residential-only area would need a long car or bus trip to enter a supermarket or an office building.

Canada

In Canada, land-use control is a provincial responsibility deriving from the constitutional authority over property and civil rights. This authority had been granted to the provinces under the British North America Acts of 1867 and was carried forward in the Constitution Act, 1982. The zoning power relates to real property, or land and the improvements constructed thereon that become part of the land itself (in Québec, immeubles). The provinces empowered the municipalities and regions to control the use of land within their boundaries. There are provisions for control of land use in unorganized areas of the provinces. Provincial tribunals are the ultimate authority for appeals and reviews.[4]

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom does not use zoning as a technique for controlling land use. British land use control began its modern phase after the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947. Rather than dividing municipal maps into land use zones, English planning law places all development under the control of local and regional governments, effectively abolishing the ability to develop land by-right. However, existing development allows land use by-right as long as the use does not constitute a change in the type of land use. A property owner must apply to change land use type of any existing building, and such changes must be consistent with the local and regional land use plans. Development control or planning control is the element of the United Kingdom's system of town and country planning through which local government regulates land use and new building. It relies on a discretionary "plan-led system" whereby development plans are formed and the public consulted. Subsequent development requires planning permission, which will be granted or refused with reference to the development plan as a material consideration.[34]

The plan does not provide specific guidance on what type of buildings will be allowed in a given location, rather it provides general principals for development and goals for the management of urban change. Because planning committees (made up of directly elected local councillors) or in some cases planning officers themselves (via delegated decisions) have discretion on each application for development or change of use made, the system is considered a 'discretionary' one.

There are 421 Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) in the United Kingdom. Generally they are the local borough or district council or a unitary authority. Development involving mining, minerals or waste disposal matters is dealt with by county councils in non-metropolitan areas. Within national parks, it is the national park authority that determines planning applications.

In England, land uses are broadly categorized into 4 Use Order Classes. Class A covers shops and other retail premises such as banks and restaurants, Class B includes workshops, factories and warehouses, Class C are residential uses and Class D are non-residential institutions, assembly and recreational uses. Each class includes subclasses that define uses in greater specificity.

Australia

The legal framework for land use zoning in Australia is established by States and Territories, hence each State or Territory has different zoning rules. Land use zones are generally defined at local government level, and most often called Planning Schemes. In reality, however in all cases the state governments have an absolute ability to overrule the local decision-making. There are administrative appeal processes such as VCAT to challenge decisions.

| State / Territory | Planning framework | Land use regulation |

|---|---|---|

ACT | Territory Plan 2008 | Land Use Policy |

NT | Planning Act | Planning Scheme |

NSW | Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 | Local Environmental Plans (LEP) |

QLD | Sustainable Planning Act 2009 repealed. Planning Act 2016 | Planning Schemes |

SA | Development Act 1993 | Development Plan |

TAS | Land Use Planning and Approvals Act 1993 | Planning Schemes |

VIC | Planning and Environment Act 1987 | Planning Schemes |

WA | Planning and Development Act 2005 | Planning Schemes |

Statutory planning otherwise known as town planning, development control or development management, refers to the part of the planning process that is concerned with the regulation and management of changes to land use and development.[35] Planning and zoning have a great political dimension, with governments often criticized for favouring developers; also nimbyism is very prevalent.

New Zealand

New Zealand's planning system is grounded in effects-based Performance Zoning under the Resource Management Act.

Singapore

The framework for governing land uses in Singapore is administered by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) through the Master Plan.[36] The Master Plan is a statutory document divided into two sections: the plans and the Written Statement. The plans show the land use zoning allowed across Singapore, while the Written Statement provides a written explanation of the zones available and their allowed uses.

Japan

Districts are classified into twelve use zones.[37] Each zone determines a building's shape and permitted uses. A building's shape is controlled by zonal restrictions on allowable floor area ratio and height (in absolute terms and in relation with adjacent buildings and roads).[37] These controls are intended to allow adequate light and ventilation between buildings and on roads.[37] Instead of single-use zoning, zones are defined by the "most intense" use permitted. Uses of lesser intensity are permitted in zones where higher intensity uses are permitted but higher intensity uses are not allowed in lower intensity zones.[37]

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Category 1 Exclusively Low-Rise Residential Zone | Designated for low-rise residential buildings. Permitted uses within these buildings include small shops, offices and elementary and high schools. |

| Category 2 Exclusively Low-Rise Residential Zone | Designated for low-rise residential buildings with above permitted uses as well as shop buildings with floor area up to 150m2. |

| Category 1 Medium and High-rise oriented Residential Zone | Designated for medium to high-rise residential buildings with hospitals, university buildings and shop buildings with floor areas up to 500m2 also permitted. |

| Category 2 Medium and High-rise oriented Residential zone | Same as Category 1 Medium and High-rise oriented Residential zone, except shops and office buildings up to 1,500m2 are permitted |

| Category 1 residential zone | Designated for residential with other permitted buildings including shops, offices and hotel buildings with floor areas up to 3,000m2 and auto repair shops up to 50m2 |

| Category 2 residential zone: | Same as Category 1 residential zone, except karaoke boxes are permitted and there are no longer building size restrictions in this zone. |

| Quasi-residential zone | Designated primarily residential with introduction of vehicle-related road facilities. Same permitted uses as Category 2 residential zone with addition of theatres, restaurants, stores and other entertainment facilities with more than 10,000m2 of floor area and warehouses. |

| Neighbourhood commercial zone | Designated for neighbourhood-based daily shopping activities. Same permitted uses as Quasi-residential zone with addition of auto-repair shops with areas up to 300m2. |

| Commercial zone | Designated for banks, cinemas and department stores. Same permitted uses as Neighbourhood commercial zone with addition of public bathhouses |

| Quasi-industrial | Designated for light industrial and service facilities. Same permitted uses as Commercial zone with addition of factories with some possible danger of environmental degradation. |

| Industrial zone | Designated for factories. Residences and shopping can be constructed but schools, hospitals and hotels are impermissible |

| Exclusively industrial | Designated for factories. All non-factory uses are impermissible. |

Philippines

The zoning system in the Philippines is explained in the Zoning Ordinance laid out by the Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB), and the cities and municipalities are responsible for regulating land use through ordinances created by each local government unit. The Philippine zoning system is divided into 11 types based on density and usage, and emphasizes the most suitable use and orderliness of the community. Definition of each density may differ between the ordinances of the local government units concerned, so one municipality may define a light density residential zone to allow 4-storey buildings, while another may only permit 2-storey buildings.[38]

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Residential | Intended or primarily used for housing. May be divided into low, medium, or high density areas. |

| Socialized housing | Mostly intended for housing underprivileged citizens, such as slum dwellers. |

| Commercial | Intended for shops, offices and businesses. May be divided into low, medium, or high density areas. |

| Industrial | Intended for industrial facilities. May be divided to light, medium, or heavy use areas. |

| Institutional | Intended for institutional establishments. May be divided to general or special use areas. |

| Agricultural | Intended for farming, aquaculture, and pasture. |

| Agro-industrial | Intended for integrated farming and manufacturing functions. |

| Forest | Intended for forestry. |

| Parks and other recreation | Intended for places of amusement and integration of nature into the community. |

| Water | Includes the municipal waters (seas and lakes), rivers, and streams |

| Tourism | Areas dedicated for tourism activity. |

France

In France, the Code of Urbanism (Code de L'Urbanisme), a national law, guides regional and local planning and outlines procedures for obtaining building permits.[10] Unlike England where planners must use their discretion to allow use or building type changes, private development in France is permitted as long as the developer follows the legally-binding regulations.[10] Zoning in French cities generally allow many types of uses. The key differences between zones are based on the density of each use on a site.[10] For example, a residential zone may have the same permissible uses as a mixed use zone. However, the proportion of non-residential uses in the residential zone would be less than in the mixed use zone.

See also

- Activity centre

- Agricultural protection zoning

- Context theory

- Ekistics

- Exclusionary zoning

- Form-based codes

- Greenspace (disambiguation)

- Open space reserve

- Urban open space

- Inclusionary zoning

- Mixed use development

- New urbanism

- Non-conforming use

- Planning permission

- Police power

- Principles of Intelligent Urbanism

- Reverse sensitivity

- Road

- Single-use zoning

- Spot zoning

- Statutory planning

- Subdivision (land)

- Traffic

- Variance (land use)

- NIMBY

- Zoning district

- Zoning in the United States

References

^ Lamar, Anika (December 1, 2015). "Zoning as Taxidermy: Neighborhood Conservation Districts and the Regulation of Aesthetics". Indiana Law Journal..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Urban Stormwater Management in the United States. National Academy of Sciences. 2009.

^ Hodge, Gerald (2014). Planning Canadian Communities. Toronto: Thomson. pp. 388–390. ISBN 978-0-17-650982-8.

^ ab Thomas, Eileen Mitchell (February 7, 2006). "Zoning". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Canada. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

^ E.g., Lefcoe, George, "The Regulation of Superstores: The Legality of Zoning Ordinances Emerging from the Skirmishes between Wal-Mart and the United Food and Commercial Workers Union" (April 2005). USC Law, Legal Studies Research Paper No. 05-12; and USC Law and Economics Research Paper No. 05-12. Available at SSRN or [10.2139/ssrn.10.2139/ssrn.712801 DOI]

^ Town and Country Planning Act 1990

^ (in German) BMVBS - Startseite. Bmvbs.de. Retrieved on 2013-07-19.

^ Sharifi, Ayyoob; Chiba, Yoshihiro; Okamoto, Kohei; Yokoyama, Satoshi; Murayama, Akito. "Can master planning control and regulate urban growth in Vientiane, Laos?". Landscape and Urban Planning. 131: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.07.014.

^ E.g., Maryland Code Article 66B, § 2.01(b) grants zoning powers to the City of Baltimore, while § 2.01(c) limits the grant of powers. By contrast, the New Jersey Municipal Land Use Law grants uniform zoning powers (with uniform limitations) to all municipalities in that state.

^ abcdef Hirt, Sonia A. Zoned in the USA: the origins and implications of American land-use regulation.

^ Arendt, Hannah (1958). The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-02598-8.

^ Talen, Emily (2012). City Rules: How Urban Regulations Affect Urban Form. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-59726-692-5.

^ abcde Rothwell, Jonathan T. and Massey, Douglas S. (2009) "The Effect of Density Zoning on Racial Segregation in U.S. Urban Areas" Urban Affairs Review. Volume 4, Number 6, pp. 779-806

^ ab Elliot, Donald (2012). A Better Way to Zone : Ten Principles to Create More Livable Cities. Island Press.

^ Julian Conrad Juergensmeyer; Thomas E. Roberts (1998). LAND USE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT REGULATION LAW § 4.2, at 80. ISBN 978-1634593069.in 1916 New York became the first city to implement this type of zoning law, later upheld in Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365 (1926). “Operating from the premise that everything has its place, [Euclidean] zoning is the comprehensive division of a city into different use zones.”

^ ab Eliza Hall (2006). "Divide and sprawl, decline and fall: A comparative critique of Euclidean zoning". U. Pitt. L. Rev: 68.

^ Jay Wickersham (2001). "Jane Jacob's Critique of Zoning: From Euclid to Portland and Beyond". 28 B.C. ENVTL. AFF. L. REV. 547, 557.

^ Jacobs, Jane. The Life and Death of Great American Cities. Vintage.

^ Katharine Baird Silbaugh: Women's Place: Urban Planning, Housing Design, and Work-Family Balance, Fordham Law Review, Vol. 76, 2008 Boston Univ. School of Law Working Paper No. 07-12. Downloaded on January 15, 2012, from: Social Science Research Network (abstract, fulltext), see page 1825

^ History of Los Angeles planning

^ Ordinance #9774 Residential Districts

^ Houston Chronicle, 12-10, 2007

^ Planetizen

^ ab Rothwell, Jonathan T. and Massey, Douglas S. (2010) "Density Zoning and Class Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas" Social Science Quarterly. Volume 91, Issue 5, pp.1123-1141

^ Natoli, Salvatore J. (1971) "Zoning and the Development of Urban Land Use Patterns" Economic Geography. Volume 47, Number 2, pp. 171-184

^ abcd Whitnall, Gordon (1931) "History of Zoning" Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Volume 155, Part 2, pp.1-14

^ 272 U.S. 365, 71 L.Ed. 303, 47 S.Ct. 114 (1926).

^ American Institute of Architects (2017). The architecture student's handbook of professional practice. Hoboken: Wiley. p. 509. ISBN 9781118738955.Euclidean zoning is the most prevalent form of zoning in the United States, and thus is most familiar to planners and design professionals.

^ Residential Investment Property Term - Zoning | Commercial Real Estate Loan. Webvest.info. Retrieved on 2013-07-19.

^ http://plannersweb.com/wp-content/uploads/2001/04/265.pdf

^ Thomas Manning, June and Marsha Ritzdorf, eds. (1997) "Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows." Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1997.

^ Zoning is Theft - Jim Fedako - Mises Daily. Mises.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-19.

^ Hsieh, Chang-Tai; Moretti, Enrico (2018-05-07). Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 2018-06-16. Lay summary – CityLab.

^ Hirt, Sonia A. (2014). Zoned in the USA: The Origins and Implications of American Land-Use Regulation. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 63–71.

^ Gleeson B. and Low N., Australian Urban Planning: New Challenges, New Agendas, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, 2000.

^ URA Master Plan 2008 website

^ abcd "Introduction to Land use Planning System in Japan" (PDF). Ministry of Land Use, Transport and Infrastructure, Japan. January 2003.

^ "4.15. Zoning Ordinance". Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board. November 26, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

- Planning Zoning

Further reading

- Bassett, E.M. The master plan, with a discussion of the theory of community land planning legislation. New York: Russell Sage foundation, 1938.

- Bassett, E. M. Zoning. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1940

- Hirt, Sonia. Zoned in the USA: The Origins and Implications of American Land-Use Regulation (Cornell University Press, 2014) 245 pp. online review

- Stephani, Carl J. and Marilyn C. ZONING 101, originally published in 1993 by the National League of Cities, now available in a Third Edition, 2012.

External links

ZoningPoint – A searchable database of zoning maps and zoning codes for every county and municipality in the United States.

Crenex – Zoning Maps – Links to zoning maps and planning commissions of 50 most populous cities in the US.- New York City Department of City Planning – Zoning History

- Schindler's Land Use Page (Michigan State University Extension Land Use Team)

- Land Policy Institute at Michigan State University

- Zoning: A Reply To The Critics